1. Introduction

Construction sites are hazardous, with 165,300 non-fatal work injuries and 21.2% of all workplace deaths in 2020 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022b). As a result, personal protective equipment (PPE), including hard hats, high visibility safety vests, safety glasses, ear protection, safety gloves, and safety footwear are part of the required uniform for anyone working on or visiting an active construction site. Federal regulations require that employers provide PPE to construction workers at no cost in the United States (Grzywacz et al., 2012). However, since the construction industry has been and continues to be male-dominated (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022a), PPE has been designed to fit men’s bodies rather than women’s (Hsiao et al., 2002), increasing the risks women face (Wagner, 2018) while reproducing gender inequality at workplaces (Acker, 1990).

High visibility safety apparel is “personal protective clothing intended to provide conspicuity during both daytime, nighttime, and other low-light conditions” (American National Standards Institute [ANSI], 2020, p. 1). The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the International Safety Equipment Association (ISEA) developed ANSI-ISEA 107-2020, the standard that regulates the design of high visibility safety apparel, including safety vests. Designs should include “correct fit and positioning…and remain in place for the expected period of use” (ANSI, 2020, p. 11). In 2015, the group acknowledged that improper fit “can expose workers to catch hazards or interfere with other protective gear, potentially compromising worker safety” (ANSI, 2015, p. 4). Construction workers are typically required to wear the Type R (roadway), Class 2 high visibility safety vest (HVSV), which provides daytime and nighttime visual conspicuity and uses additional amounts of high-visibility materials to define the human form more effectively and longer detection from longer distances (ANSI, 2020).

The vest’s primary goal is 360-degree visibility, meaning the person wearing the vest can be seen from any direction. To be seen, the background material must be high visibility fabric and have a set number of reflective bands or stripes in specific locations. The minimum required background material is 540 square inches (0.35 m2) for small-sized workers, then 775 square inches (0.50 m2) for any other worker, with incremental sizing allowed above 775 in2, but not between 540 in2 and 775 in2 (ISEA, 2020). This material requirement yields safety vests that are too large for smaller-sized workers, especially women.

To better understand women’s experiences with high visibility safety vests and develop solutions to improve poorly fitting vests, we orchestrated a two-day “Verifying Everyone’s Safety Together” (VEST) Hackathon in Spring 2022. At hackathon events, end users, designers, and developers collaborate to redesign and improve a product. Our study followed a feminist hackathon model (D’Ignazio et al., 2016) and sought to answer these questions:

1. How do current safety vest designs impact wearers at work?

2. How can a feminist hackathon be used to understand wearers’ problems (especially women’s problems) with the safety vest and ways to improve the vest?

2. Literature Review

The construction industry is male-dominated, with 89% of the workforce identifying as men and a majority being white men (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022a). As a result, PPE design accommodates the working majority (Flynn et al., 2017; Hsiao et al., 2002). The male labor pool within the construction industry is shrinking (Goldenhar et al., 1998), caused by retirements and an aging workforce, an education system that does not value technical education, and the lack of new, younger people entering the industry (Menches & Abraham, 2007). The shrinking labor pool has caused recruitment efforts to turn to underrepresented groups, including women, to increase the workforce population. However, when women arrive on site, they receive PPE that does not fit (Goldenhar et al., 1998; Oo & Lim, 2020; Wagner, 2018), reducing women’s self-efficacy (Wagner et al., 2013).

Poorly fitting safety equipment can be “ineffective and hazardous” (Erickson, 1987, p. 34) if it causes the wearer to get snagged on items, falls off because it is too loose, or distracts the wearer with constant readjustment (Curtis et al., 2018; Hsiao et al., 2007; Onyebeke et al., 2016; Sokolowski et al., 2022).

Since women are not just “scaled down versions of men” (Erickson, 1987, p. 36), smaller-sized PPE designed for male rather than female body types (Hsiao et al., 2007) creates additional “gender-based hazards” in already-hazardous construction environments (Turner et al., 2021, p. 841).

2.1 Hackathons

A hackathon is a one- to two-day event where people look at a problem and try to find a technical solution (Richterich, 2019). Hackathons often invite people who use the product to participate so the finished design or product can better fit their needs. Although initially used to improve computer and software applications in the tech industry, hackathons have evolved into events that find solutions for social issues that can use technology to help - including diversity and inclusion (Htun, 2019), breast pumps (D’Ignazio et al., 2016), and affordable housing (Ivory Innovations, 2023).

Hackathons are often criticized for only providing technological fixes - technology band-aids that do not get to the root of the problem (Hope et al., 2019). Many problems are multifaceted, requiring both social and technological change, so ignoring the social aspect to focus solely on technical solutions may not yield lasting impacts (D’Ignazio et al., 2020). Chau and Gerber (2023) state the need for recruiting more diverse participants and considering positionality throughout the analysis of hackathons over time.

To develop solutions that analyzed both technical and social solutions, D’Ignazio et al. (2016) developed a feminist hackathon model to improve the breast pump. Drawing on the six qualities of feminist interaction design proposed by Bardzell (2010) - pluralism, participation, advocacy, ecology, embodiment, and self-disclosure - D’Iganzio et al. (2016, p. 2) offered six principles for a feminist hackathon, stating that a feminist hackathon:

1. Thinks ecologically about the problem space and fosters technical and non-technical solutions.

2. Favors learning over invention in order to introduce a more holistic understanding of a problem space that specifically includes and values the perspectives of marginal users and subject matter experts.

3. Prioritizes listening over ideating to acknowledge that while the designer’s position is powerful, her perspective is partial. Structured listening creates an inclusive environment and values non-specialist ways of knowing.

4. Sees the production of new social relations (stakeholder conversations) as a more effective path to change than the production of objects (rewarding winners).

5. Intentionally architects media attention in order to advocate for the issue.

6. Nurtures and sustains communities of practice after the fact.

Building on these principles, our paper presents the development and implementation of a design process where users were invited to participate in revisioning the safety vest to better serve their needs for safety, comfort, fit, and function. Few studies have analyzed the implementation of feminist hackathons (D’Ignazio et al., 2016; D’Ignazio et al., 2020; Hope et al., 2019), and to date, we are unaware of any feminist hackathon held to improve safety equipment for women working in construction. Employing mixed methods, our VEST Hackathon extends the literature on feminist hackathon assessment while simultaneously aiming to improve women’s experiences with poorly fitting safety vests by garnering their input and expertise. Additionally, our study expands on ways poor fitting PPE impacts women’s sense of self-efficacy, identity, and other professional implications (Wagner et al., 2013).

The remainder of the paper will discuss the setting and research methods used for the VEST Hackathon. We then discuss how we implemented D’Ignazio et al.’s (2016) six feminist design principles at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, noting participants’ experiences throughout the event. Finally, we end with a discussion of the limitations and contributions of the feminist hackathon.

3. Research Methodology

Our VEST Hackathon was inspired by a student’s senior project, which explored the fit of safety vests for construction workers, discovering women were disproportionately impacted by improperly fitting PPE (Galvez-Puentes, 2020). The VEST Hackathon was held in San Luis Obispo, California, on April 11-12, 2022. It was coordinated by a group of California Polytechnic State Univeristy undergraduate students and faculty members in the construction management, social sciences, and experience management departments. The construction management students had worked on or visited construction sites, typically in a management or supervisory role, and had encountered issues with ill-fitting PPE.

The hackathon was advertised to California Polytechnic State University’s construction management advisory council members, at multiple career fairs to recruiting companies, and via social media (LinkedIn and Instagram). Thirty-seven official registrants (24 women, 13 men) attended the hackathon from sixteen different companies, and approximately 12 students and four faculty participated from the construction management major came by the hackathon between classes. Event attendees included faculty and alums, construction industry workers, construction technology providers, safety officers, and safety vest manufacturers.

To assess attitudes towards wearing safety vests on worksites and to evaluate a feminist safety vest hackathon, we employed a mixed-methods design, which included the use of closed and open-ended, pre- and post-surveys, participant observation at the hackathon, design reflection journals, and interviews. This combination of methods enabled us to get at the “process of making meaning” (Esterberg, 2002, p. 152) and the “active process of interpretation or sense-making” (Emerson et al., 1995, p. 8) by engaging actively with design team participants and asking probing questions for clarification throughout the event.

Before the hackathon, registered participants were asked to complete an online survey (n=20) asking them to describe their experiences with and perceptions of their vests in varying contexts. Demographic information was collected and Likert-scale questions asked participants to indicate how much their vest impacts their respect, confidence, and perception of abilities. Multiple choice questions were asked about vest fit and safety. Open-ended questions were also included and asked about their reasons and goals for participation and what they hoped to accomplish by attending the hackathon. Of the 37 registrants, only 20 completed the pre-survey (3 men, 17 women). Jottings and fieldnotes were taken while interacting with teams, expanding and writing notes-on-notes and analytic memos after the event (Emerson et al., 1995; Kleinman, 2007; Kleinman & Copp, 1993).

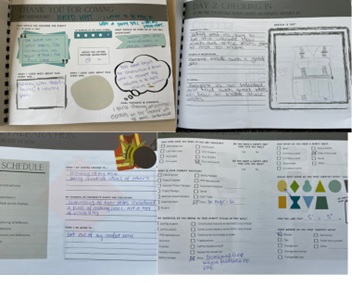

Throughout the two days (See Figure 1 for the event schedule), the undergraduate research team conducted interviews (n=16) and performed field observations. Participants were provided a bound design reflection journal to write down their daily goals, reflect, sketch prototype designs, and record ideas and feelings. The design reflection journal asked for participants’ demographic information and included sketching, note-taking, and reflection pages. Each table also held large sheets of sketch paper to record and share design ideas. During interviews, these images, quotes, and designs were used to elicit information from hackathon participants about their workplace experiences that would have been difficult to discover through the interview guide alone (Harper, 2002; Virole & Ricadat, 2022). Triangulating the data enabled us to contextualize the sketches and jottings by individual and industry.

After the event, a survey was sent to participants to understand event satisfaction, conversations, and speakers, if they would attend future similar events, if the visual displays were relevant and inspirational, and if this event was productive and important for the industry. Open-ended questions allowed participants to expand upon what they learned or felt was achieved at the hackathon, the impact of the hackathon, what they shared with others about the event, and suggestions for future hackathons. Unfortunately, only four respondents completed the post-survey.

4. Setting

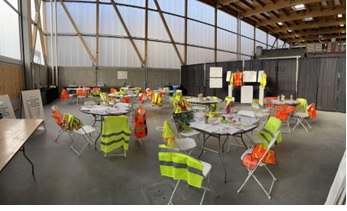

The hackathon was hosted in a large, open-aired shop. The room was set up so people could easily interact with their team members and other teams and access hacking supplies. Circular tables where teams of six could easily work together were spread around the room. The tables were small enough so all members could reach the middle of the table to sketch, point, and work collaboratively. Each table was set up with materials for hacking (safety vests, scissors, pins), materials for generating and sharing ideas and reflecting (design reflection journals, markers, sketch paper), informational materials (ANSI/ISEA standards reference page, square inches page), and materials that might be carried in vests (tape measures, water bottles, sanitary napkins and tampons, and carpenter’s pencils).

Additional supply tables held materials to make new vests along the sides of the room like a sewing machine, extra zippers, reflective banding, and safety pins (see Figure 2). The shared supply tables provided opportunities for participants to meet with other teams, congregate, and chat about ideas while waiting for the sewing machine or deciding which fastener to use for their vest: velcro or zippers? We provided enough materials so participants could “Frankenstein” a vest - taking apart pieces of vests they liked, piecing them together to create new vests that fit, and highlighting features they wanted (pockets, water bottle holders, ergonomic adjustments, and ID card displays).

5. Analysis and Results

Our analysis draws on grounded theory principles (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Charmaz, 2006), symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969), feminist fieldwork (Kleinman, 2007), and feminist hackathons (D’Ignazio et al., 2016; D’Ignazio et al., 2020; Hope et al., 2019). After the event, the research team analyzed the pre- and post-survey responses, transcribed and analyzed the interviews, and reviewed fieldnotes and print materials generated at the event (sketches and design reflection journals). The second author worked with one student to code fieldnotes and search for patterns in the survey and interview data, beginning with open coding and proceeding to focused coding. Below, we outline the feminist hackathon principles, incorporating data from the event.

5.1 Principle 1: Thinking about the Problem Space Ecologically

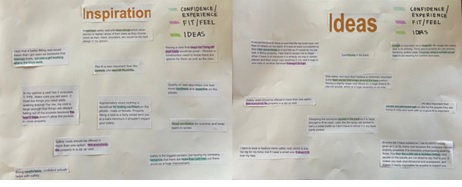

Thinking about the hackathon and the problem ecologically was approached following Barzdell’s concept of ecology (as cited in D’Ignazio et al., 2016, p. 7). We examined the vest within the broader socio-technical web to discover technical and non-technical solutions. To help participants think about the vest within the broader social context (Bardzell, 2010; D’Ignazio et al., 2016), quotes from a previously conducted survey-based student research project (Galvez-Puentes, 2020) were hung on display boards at the front of the room (See Figure 3). These quotes provided some ideas and inspiration to hackathon participants when designing a vest and were selected to include both technical and social interactions of the wearer. For example, one quote that looked at a technical solution to improve vests requested an “iPad pocket in the back.” Another quote noted how a poorly fitting safety vest impacted their social interactions:

At every job I have worked on, I am ALWAYS initially given an L or XL men’s vest because the company has not been properly prepared. It is incredibly embarrassing wearing those. You look like a little kid in daddies [sic] clothes, and people on the jobsite are not afraid to say that to you. It makes you look unprofessional and unprepared, and makes it nearly impossible for anyone to respect you.

These quotes highlighted problems for the teams to address.

Figure 3 Display boards with quotes from a student research project to help participants think about the broader socio-technical problem of safety vests.

Women respondents (n=17) felt it was important to participate in the VEST Hackathon for a variety of reasons, including “to network,” “to promote safety,” “to empower women,” and “to make the industry more inclusive.” One respondent liked the opportunity for “supporting women in construction while giving field input.” Several women noted that improperly fitting vests had been a problem for them as workers in construction. One woman wanted to participate because “I have had an issue with women's safety vests for years. It is time to make a change!” Similarly, another woman noted, “Today we have quite a few women out in the field, working on site. I believe we need construction clothing that fits us correctly so we can get our job done comfortably.” Although most participants noted that safety vests were required at their worksites, and, in other words (18 of 20), wearing them was not negotiable, two confessed to not wearing them in the past.

One respondent wrote, “lack of proper fitting garment” as their reason, and another provided the following account: “Because I was walking quickly through and they can be a nuisance.”

Regardless of the gender of the pre-survey respondent, the desire and motivation to promote inclusion and belonging were common reasons for wanting to participate in the VEST Hackathon. One respondent noted they wanted to “help continue women’s visibility in the industry.” One man wrote they wanted to show “support of our diverse industry” and admitted in parentheses that they had “never thought much about this issue [fit of safety vests] before as a man.” One man noted his expectation for the day was to “learn about issues women face in the workplace that most people are unaware about.” A woman submitted the following reason for participating, “[I w]ant to learn what is important to women in a vest. Want to show support for women in construction especially with and initiate to help them gain a bigger sense of belonging in the industry.” Before the event, people were generally hoping to “promote women entering construction,” “to make women more comfortable with careers in construction,” “to create better fitting vests,” and to “help students make a better fitting, more accessible, safer safety vest.” Next, we analyze Principles 2 and 3 together.

5.2 Principle 2: Value Learning over Invention and Principle 3: Prioritize Listening over Ideating

Principles 2 and 3 from D’Ignazio et al. (2016) are complementary and require recognizing the problem holistically, which requires listening to and valuing each participant’s contributions while ideating and creating a technical solution collaboratively. The problem of the vest is multidimensional - with influence from industry demographics, inclusion, equity, (un)awareness, the efficiency of ordering, different body types, and safety standards. Various stakeholders’ interests govern the design and accessibility of workers, but especially women’s vests. As such, technical constraints and possibilities, and a broader understanding of the overall problem women face within the construction industry, should be considered. Many participants were women who wear safety vests daily, serving as subject matter experts for fit and function while also representing marginalized users on a construction site.

Throughout the hackathon, participants shared different experiences and insights to help guide design ideas that would benefit the wearer. One carpenter’s apprentice intern shared that her safety vest got snagged on rebar right next to an embankment when carrying a load of lumber. Had she lost her balance, she could have fallen off the embankment or been impaled by rebar, injuring or possibly killing her. A safety representative shared that all members of her construction team have a picture of their loved ones in their hard hats to remind them why they work safely every day. One team incorporated an area to post a family picture within their vest to display why safety matters to them. Two project managers brought and displayed the vests they wear daily. Their vests function as tool belts carrying electrolyte packs, iPad or pads of paper, gum, flashlight, mini screwdriver, pens and pencils, a tape measure, blue masking tape, and more. The vest becomes heavy with all these items, and they invited other participants to try on their vests to show how weight was distributed. Two teams developed inner straps and adjustments to help distribute weight better across the vest.

Safety officers and vest manufacturers discussed vest compliance, the importance of 360-degree visibility, and provided expertise on standards and ways to design that would make manufacturing more efficient, reducing costs. One student researcher displayed three vest prototypes she developed before the hackathon and shared her experiences creating sample vests and the problems she encountered. Sharing her process allowed others to learn from her experiences and also gave permission to end the hackathon with an imperfect product. Prototypes could have imperfections but still reflect a step towards industry change.

Several comments from the design reflection journals (see Figure 4) stated that learning, collaboration, and networking were what they enjoyed most about the hackathon. Although manufacturers were there to provide expertise, they learned about fit and function from expert vest wearers. One safety vest manufacturer wrote, “from a practical standpoint, it is really helpful to gain a better insight to the needs of a vest - beyond the safety/protection compliance factors.” Another stated it was “interesting to hear vests are considered a piece of clothing/tool, not a tool of visibility.” Although manufacturers came into the event thinking about regulations and compliance, they left the event reflecting on the variety of needs that wearers have, realizing that vests impact more than just worker safety and visibility.

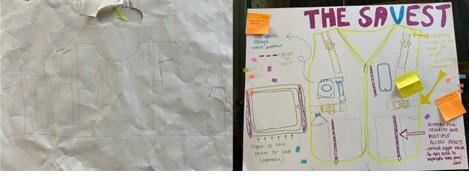

Throughout the hackathon, listening and reporting sessions discussed progress and challenges and requested feedback from other users. At the event’s conclusion, vests and corresponding design artwork were displayed depicting some key features and considerations. Six unique designs were developed with different features (water bladders, pockets, and a place for a family picture), ergonomic straps, function, user needs (trade worker versus project manager), cost, and ways to adjust fit. Two teams’ finished prototypes are shown in Figure 5.

5.3 Principle 4: Production of Social Relations for Change

Actively engaging and critiquing teams’ ideas and improving prototypes yielded opportunities to network and grow through collaboration. When reflecting on the event in her journal, one participant expressed the power of collaborative design, noting, “Anything can be made better when we put our heads together.” Others spoke positively about the collaboration opportunities, stating they most enjoyed “collaborating with people caring about the same things,” or “meeting new people within the industry and collaborating to solve a problem.” Ideas were sketched to collaborate on improvement ideas, with different design iterations developed and enhanced throughout the event. Figure 6 shows the first and last design iterations produced by one team.

Figure 6 Participant-generated art and evolution of design from day 1 to day 2. The left drawing shows the original vest design developed on day one for the lightning pitches. The right drawing shows the final vest design at the event’s conclusion, with the elements included and reasons for the recommended vest modifications.

The hackathon setup allowed participants to mingle and share. Women’s experiences were identified and centered through presentations, casual conversations, and design iterations. Throughout the day, feelings of belonging arose. One respondent reflected, “If there is one small thing that we could do like providing a better fitting vest, that might make a big difference every day for an employee…letting them know they belong, are valued, and are considered when provided safety equipment.” The hackathon also allowed women working in the industry to network. Conversations grew beyond vest design to sharing best practices with other women, such as what to pack in a vest for efficiency, and strategies for dealing with difficult situations on site.

Reviewing participant comments in the design reflection journals, the event overall was one where people felt “empowered” and left feeling like there are people in the construction industry who want to make the industry more inclusive, similar to the findings from D’Ignazio et al.’s (2020) hackathon where participants felt a sense of empowerment, solidarity, and confidence. One participant said she hopes to remember “there is a HUGE group of people in the industry that care about making this an inclusive space for women.”

Post-event survey results revealed that participants were satisfied with their involvement. One woman claimed, “Event size was perfect, LOVED meeting women working in the industry, interest of young people. Topic was interesting and relevant,” while another remarked that the participants’ enthusiasm was good. They said, “It was fulfilling just to be around the energy. From a practical standpoint, as a Vest manufacturer, it was really helpful to gain a better insight to the needs of a vest - beyond the safety-protection compliance factors.” Another event participant said, “I loved talking and working with other people and seeing their ideas. Greatest takeaways were that the changes aren’t necessarily drastic but more versatility is needed in design.”

Working collaboratively to make small but needed changes was rewarding to participants. One said, “I liked how excited everyone was about the event. You could feel the energy in the room. It was refreshing to see what ideas we can come up with when we work together and let ourselves get creative.”

A man stated, “I gained a better appreciation of the social-psychological impact of women not having enough access to products designed for their body shape,” while a woman noted, “I feel like I am definitely going to be more aware of my PPE that I wear every day and will likely bring up ways to improve them.”

5.4 Principle 5: Architect Media Attention

As noted by D’Ignazio et al. (2016), “A feminist hackathon intentionally architects media attention in order to advocate for the issue” (p. 2). People who attended our VEST Hackathon were interested in doing so for their and other workers’ safety on job sites. Some women were in positions to advocate for themselves more so than others. After the event, participants shared pictures and summarized their participation on social media, such as LinkedIn. One worker stated, “We shared photos and a summary of the event in a positive light with our advertising department. I plan to call our head safety guy as well to tell more about the event and what we can do.” Another participant said, “[this] was a valuable event because it focused attention on an important problem investigating potential solutions.” As we plan for our second hackathon, we are brainstorming ways to better attract media attention to amplify the women workers raise, as this area has room for improvement.

5.5 Principle 6: Nurture and Sustain Communities of Practice

D’Ignazio et al. (2016) theorized that “change may be affected by creating and nurturing new social relationships” (p. 10) to finish the job started at the hackathon. One participant noted that revising the ANSI/ISEA 107-2020 standard is the necessary next step for real change. From connections created at the hackathon, we have been invited to participate in the preliminary ANSI/ISEA design meeting to provide recommendations for updated vest standards in Spring 2023.

VEST Hackathon attendees found the event worthwhile and were interested in participating in future hacks. They thought our VEST Hackathon was a “great start,” but that we “need to execute” the prototype ideas to impact change. Participants recommended that we “think about getting the AGC (Association of General Contractors) or another industry group with some lobbying power to help Cal-OSHA, DIR, DOL, etc. get rid of silly square inch minimums that make giant vests or smaller people unnecessarily dangerous and counter to safety.”

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Building on feminist interaction design principles (Bardzell, 2010; D’Ignazio et al., 2016), this research presented the development, implementation, and results of a feminist hackathon where users were invited to participate in revisioning the safety vest to better serve their needs for safety, comfort, fit, and function. The goal of the VEST Hackathon was to improve the fit of vests for varying body types by gaining insights from diverse industry workers. We hosted a 2-day event where six teams redesigned vests, cut them apart, and constructed prototypes, which were then presented to industry workers and vest manufacturers for feedback. Quantitative and qualitative data, including surveys, daily reflection journals, fieldnotes, and semi-structured interviews, were collected and analyzed to conceive new design and safety features for different body types and wearer needs. This study expands the research surrounding feminist hackathon design principles by including women in collaborative design processes to understand and improve the fit of safety vests for women on construction sites.

Although six prototypes were developed during the hackathon, there were limitations to our study. A small group of people attended, presenting fewer viewpoints instead of a complete cross-section of the construction industry and the entire supply chain. For example, no trades workers attended, which one safety manager noted as an issue since “most teams focused on surveyor vests which already exist for women.” They recommended that we “needed to focus on one for [the] basic field.” Manufacturers in attendance stated that distributors should have a voice since women’s vests exist, but they need to get to the end users. Finally, although held at a university campus, a limited number of students attended, a shortcoming noted by industry attendees.

Following D'Ignazio and colleagues (2016), “We believe the hackathon, particularly when informed by a feminist design perspective, is a viable form to gather collective energy around a problem, stage stakeholder conversations, build community and influence individuals, communities, and institutions in positive ways” (p. 12). To improve data collection at future hackathons, we have several recommendations. First, build times into the schedule for participants to write in their design reflection journals and have interview respondents walk interviewers through their ideas as part of the interviewing process to elicit responses and to probe about experiences with the artifact at the event and in the primary places of use. Second, avoid conducting interviews while teams work on prototypes or consider interviewing some team members together or following up with them after the event to ask additional questions. Third, incorporate more demographic measures into pre- and post-survey designs to better analyze the intersection of additional variables, including gender, race, ethnicity, and age, and do more to encourage post-survey response rates.

Finally, future researchers should consider hosting focus groups with marginalized users/workers and industry leaders following hackathons to continue stakeholder conversations, sustain communities, and impact both technical and social changes or to host a follow-up hack where participants can debut further developments to their prototypes. Since the VEST Hackathon, we have contacted ANSI’s high visibility working group, and they have invited California Polytechnic State University faculty and students to present results discovered from the VEST Hackathon. We will participate in their first design meeting as they consider revisions to the ANSI-ISEA 107 design standards, which will go into effect in 2025.