Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

GE-Portuguese Journal of Gastroenterology

versão impressa ISSN 2341-4545

GE Port J Gastroenterol vol.24 no.6 Lisboa dez. 2017

https://doi.org/10.1159/000461591

IMAGES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Hematidrosis, Hemolacria, and Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Hematidrose, Hemolacria e Hemorragia Gastrointestinal

Artur Sérgio Gião Antunes, Bruno Peixe, Horácio Guerreiro

Gastroenterology Departament, Centro Hospitalar do Algarve, EPE, Faro, Portugal

* Corresponding author.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, Vasculitis, Purpura

Palavras-Chave: Hemorragia gastrointestinal, Vasculite, Purpura

A 66-year-old male was admitted to the internal medicine department for asthenia and lower-limb edema. He also reported a self-limited respiratory tract infection in the previous 3 weeks, and afterwards he developed abdominal fullness. From his medical record, we registered long-standing type 2 diabetes, and the patient was chronically treated with ramipril plus hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension.

On examination, for the exception of symmetric lower- limb edema, no other abnormalities were seen. His initialblood tests were as follows: hemoglobin 14,0 g/L; white blood cell count 8.2 × 10 9 /L; neutrophils 92.9%; platelets 264 × 10 9 /L; Na 134 mmol/L; K 4,2 mmol/L; blood urea nitrogen 61 mg/dL; creatinine 3.3 mg/dL; Creactive protein 19 mg/L, and INR 1.0. Urinalysis showed 1,178.7 mg/dl of proteinuria, with 3–5 red and white blood cells per high-power field, without dysmorphic cells. Total cholesterol (353 mg/dL) and triglyceride (261 mg/dL) were increased, and serum protein electrophoresis revealed hypoalbuminemia (1.8 g/dL). In a 24-h specimen of urine, protein was 2,716 mg.

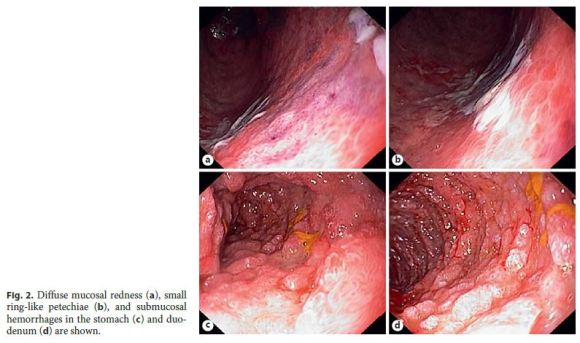

During hospitalization, the patient developed a sudden episode of hematemesis. On physical examination, he had hemodynamic stability and epigastric tenderness without guarding or rebound tenderness. The upper endoscopy showed diffuse mucosal redness, small ring-like petechiae, submucosal hemorrhages, and superficial ulcers in the gastric body, antrum, and duodenum (Fig. 1).

There was a rapid clinical deterioration, with the development of hemolacria (bloody tears), hematidrosis (bloody sweat), macroscopic hematuria, and appearance of a palpable purpura on the lower limbs, abdomen, and trunk (Fig. 2). The patient developed multiple organ failure and required hemodialysis and mechanical ventilation. Given the clinical set, we considered the diagnosis of a vasculitis and started corticosteroids (1,000 mg of methylprednisolone per day). A chest high-resolution computed tomography scan was performed, and besides bilateral pleural effusion, no other abnormalities were noticed.

Serologies for HIV, hepatotropic viruses, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test, and antistreptolysin O antibodies were negative. Blood tests for autoimmunity (antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies, and serum cryoglobulins) and blood cultures were also normal. With corticotherapy, there was a hasty improvement, and a kidney biopsy was performed.

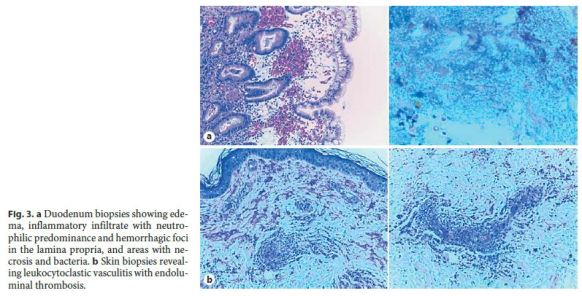

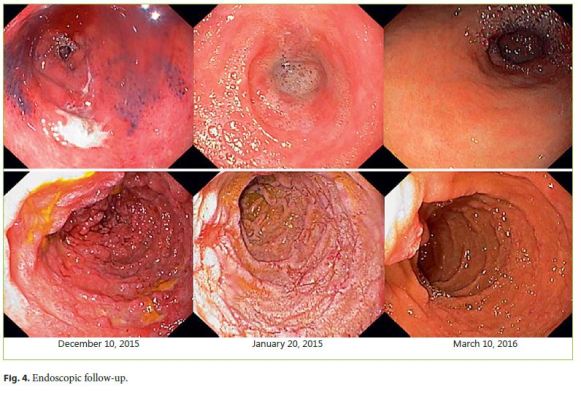

Histology from the stomach, duodenum, and skin (Fig. 3) was compatible with vasculitis, and the kidney biopsy with immunofluorescence showed mesangial IgA deposits. We established the diagnosis of a Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP). The patient continued with oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg) for 3 months, and subsequent endoscopies confirmed the good evolution (Fig. 4).

HSP is an IgA-mediated small-vessel vasculitis that most commonly affects children. In adults, it is extremely rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.1–1.2 per million. Its etiology is still unclear, but a recent history of respiratory tract infection is reported in 90% of the cases. Other precipitating factors already identified are medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors, or antibiotics), tumors (non-small cell lung cancer, prostate cancer, or haematological malignancies), food allergies, vaccinations, and insect bites [1].

Gastrointestinal involvement is common in HSP (in up to 85% of the patients), varying from colicky abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting to intestinal hemorrhage, intussusceptions, and pancreatitis [2].

HSP should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with gastrointestinal bleeding, palpable purpura, and acute renal injury [2, 3].

References

1 Watts RA, Carruthers DM, Scott DG: Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis: changing incidence or definition? Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995;25:28–34. [ Links ]

2 Sohagia AB, Gunturu SG, Tong TR, et al: Henoch-Schonlein purpura – a case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2010;2010:597648. [ Links ]

3 Juthpratuck W, Elshenawy Y, Salet H, et al: The clinical implications of adult-onset Henoch-Schonlein purura. Clin Mol Allergy 2011;9:9. [ Links ]

Statement of Ethics

This study did not require informed consent or review/approval

by the appropriate ethics committee.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

* Corresponding author.

Dr. Artur Sérgio Gião Antunes

Gastroenterology Department, Centro Hospitalar do Algarve, EPE

Rua Leão Penedo

PT–8000-386 Faro (Portugal)

E-Mail sergiogiao@hotmail.com

Received: November 24, 2016; Accepted after revision: January 11, 2017