Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

GE-Portuguese Journal of Gastroenterology

versión impresa ISSN 2341-4545

GE Port J Gastroenterol vol.25 no.1 Lisboa feb. 2018

https://doi.org/10.1159/000480704

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Efficacy of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in the Treatment of Biliary Complications following Liver Transplant: 10 Years of a Single-Centre Experience

Eficácia da colangiopancreatografia retrógrada endoscópica no tratamento de complicações biliares após transplante hepático: 10 anos de experiência de um centro

Ana Rita Alvesa, Dário Gomesa, Emanuel Furtadob, Luís Toméa

aServiço de Gastrenterologia, and bUnidade de Transplantação Hepática Pediátrica e de Adultos, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

* Corresponding author.

ABSTRACT

Background and Aims: Biliary tract complications following liver transplant remain an important source of morbidity and mortality. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has become a common therapeutic option before other invasive procedures. The aim of this study was to evaluate ERCP efficacy in managing this type of complications. Methods: Retrospective study of all patients who underwent therapeutic ERCP due to post-liver transplant biliary complications between September 2005 and September 2015, at a deceased donor liver transplantation centre. Results: Therapeutic ERCP was performed in 120 patients (64% men; mean age 46 ± 14 years). Biliary complications were anastomotic strictures (AS) in 70%, non-anastomotic strictures (NAS) in 14%, bile leaks (BL) in 5.8%, and bile duct stones (BDS) in 32%. The mean time between liver transplant and first ERCP was: 19 ± 30 months in AS, 17 ± 30 months in NAS, 61 ± 28 months in BDS, and 0.7 ± 0.6 months in BL (p < 0.001). The number of ERCP performed per patient was: 3.8 ± 2.4 in AS, 3.8 ± 2.1 in NAS, 1.9 ± 1 in BDS, and 1.9 ± 0.5 in BL (p = 0.003). The duration of the treatment was: 18 ± 19 months in AS, 21 ± 17 months in NAS, 10 ± 10 months in BDS, and 4 ± 3 months in BL (p = 0.064). Overall, biliary complications were successfully managed by ERCP in 46% of cases, either as an isolated procedure (43%) or rendez-vous ERCP (3%). Per complication, ERCP was effective in 39% of AS, in 12% of NAS, in 91% of BDS, and in 86% of BL. Globally, the mean follow-up of the successful cases was 43 ± 31 months. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and/or surgery were performed in 48% of patients in whom ERCP was unsuccessful. The odds ratio for effective endoscopic treatment was 0.2 for NAS (0.057–0.815), 12.4 for BDS (1.535–100.9), and 6.9 for BL (0.798–58.95). No statistical significance was found for AS (p = 0.247). Conclusions: ERCP allowed the treatment of biliary complication in about half of patients, avoiding a more invasive procedure. Endoscopic treatment was more effective for BDS and BL.

Keywords: Liver transplantation, Biliary complications, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Treatment efficacy

RESUMO

Introdução: As complicações biliares após transplante hepático são uma fonte importante de morbilidade e mortalidade. A colangiopancreatografia retrógrada endoscópica (CPRE) é a primeira opção de tratamento em muitos casos, previamente a procedimentos mais invasivos. O objetivo deste trabalho foi avaliar a eficácia da CPRE no tratamento destas complicações. Doentes e métodos: Estudo retrospetivo de todos os doentes submetidos a CPRE terapêutica devido a complicações biliares após transplante hepático, entre setembro de 2005 e setembro de 2015. Resultados: Incluídos 120 doentes submetidos a CPRE terapêutica, sendo 64% do sexo masculino, com idade média de 46 ± 14 anos. Complicações biliares: estenose da anastomose (EA) em 70%, estenose não anastomótica (ENA) em 14%, coledocolitíase em 32% e fuga biliar (FB) em 5,8%. Tempo entre transplante e primeira CPRE (meses): 19 ± 30 nas EA, 17 ± 30 nas ENA, 61 ± 28 na coledocolitíase e 0,7 ± 0,6 na FB (p < 0,001). Número de CPRE por doente: 3,8 ± 2,4 nas EA, 3,8 ± 2,1 nas ENA, 1,9 ± 1 na coledocolitíase e 1,9 ± 0,5 na FB (p = 0,003). Duração do tratamento (meses): 18 ± 19 nas EA, 21 ± 17 nas ENA, 10 ± 10 na coledocolitíase e 4 ± 3 nas FB (p = 0,064). Globalmente, a CPRE terapêutica foi eficaz em 46% dos casos (como procedimento isolado em 43% e por rendez-vous em 3%). Eficácia por complicação: 39% nas EA, 12% nas ENA, 91% na coledocolitíase e 86% nas FB. O tempo médio de follow-up foi de 43 ± 31 meses. Em 48% dos doentes, foi realizada terapêutica por colangiografia percutânea e/ou cirurgia por ineficácia da CPRE. Odds ratio para um tratamento endoscópico eficaz: 0,2 para ENA (0,057–0,815), 12,4 para coledocolitíase (1,535–100,9) e 6.9 para FB (0,798–58,95). Não houve diferenças estatisticamente significativas para a presença de uma EA. Conclusões: A CPRE foi eficaz no tratamento de complicações biliares após transplante hepático em cerca de metade dos casos, evitando outros procedimentos invasivos. O tratamento endoscópico foi particularmente eficaz em casos de coledocolitíase e FB.

Palavras-Chave: Transpante hepático, Complicações biliares, Colangiopancreatografia retrógrada endoscópica,·Eficácia terapêutica

Introduction

Biliary complications following orthotopic liver transplant (LT) are a common source of morbidity and affect patient survival [1]. The overall reported incidence of biliary complications is 5–30% and they are more frequent following living donor LT [1–3]. Biliary complications include anastomotic strictures (AS), non-anastomotic strictures (NAS), also called ischaemic type biliary strictures, bile duct stones (BDS), biliary leaks (BL), and other less common conditions [1, 3]. Multiple risk factors are identified, including recipient factors (age, advanced liver dysfunction), graft factors (prolonged cold and warm ischaemia time), surgical factors (living or deceased donor, surgical technique) and postoperative course factors (hepatic artery thrombosis), among others [1]. Despite the knowledge of the risk factors and the medical and surgical improvements, biliary complications are still considered one of the most important issues in the management of post-LT patients [1, 4].

Treatment of biliary complications may be complex and involves endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), or surgery. In some cases, a combination of different techniques may be necessary [4]. Nowadays, ERCP is commonly the first treatment modality and is considered the gold standard for patients with duct-to-duct anastomosis [1, 5]. PTC is reserved for cases of unsuccessful ERCP or as a complement to ERCP (rendezvous technique) [1]. Surgery is usually indicated for refractory or severe conditions not manageable by less invasive techniques [1]. Although it is a first-line therapy, the reported outcomes for ERCP in the literature are variable, mainly for bile duct strictures, and most data are from retrospective studies [5–8].

The purpose of this study was to describe how ERCP has been used in the management of biliary complications following LT in our centre. The principal aims were: (a) to describe the endoscopic treatment, (b) to evaluate ERCP efficacy, and (c) to analyse treatment-related factors associated with better outcomes.

Patients and Methods

A single-centre retrospective study of all ERCP performed between September 2005 and September 2015 in adults with biliary complications following deceased donor LT took place at Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra. In a primary phase, all patients who underwent ERCP were studied. Since our aim was to describe therapeutic procedures and evaluate ERCP efficacy, only Collected data included patient demographics (age, gender), aetiology of liver disease, biliary complications, time between LT and biliary complication, number of ERCP per patient, duration of treatment, endoscopic therapy (stent placement, dilatation, stone removal), outcome, follow-up time, and complementary or alternative treatments to ERCP (PTC and/or surgery). Follow-up of all patients was evaluated in March 2016 and only patients with complete treatment were included (patients with ongoing treatment were not included).

ERCP was considered effective when biliary complication was successfully managed solely by ERCP and no other procedure (PTC or surgery) was performed. ERCP was also considered effective when a PTC was performed at some time during the treatment to allow access to the biliary duct (rendez-vous). However, the results are presented separately. ERCP was considered ineffective when the manifestations of biliary complication remained or recurred after ERCP and alternative treatment was performed, such as PTC, surgery or both. Cases in which it was not possible to cannulate the papilla or the desired bile duct were classified as a technical failure. Cases of mortality unrelated to biliary complication occurring prior to the efficacy evaluation were also registered.

ERCPs were performed using Olympus TJF-145 Video Duodenoscopes. There is not a predefined protocol regarding endoscopic treatment of biliary complications after LT in our unit. The type of treatment (dilation and/or stent placement), the diameter, size and number of stents, and the frequency of stent replacement were determined according to the gastroenterologists clinical judgement at the procedure and patient evolution. Plastic stents were used and strictures were dilated by using high-pressure pneumatic biliary balloons ranging from 4 to 10 mm.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS ® ) version 20. Descriptive information is presented as a proportion or mean ± standard deviation (SD) according to the type of variable (categorical or quantitative). Normality tests were performed. Statistical tests for categorical variables included the χ 2 test or the Fisher exact test and for quantitative variables we used the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney, ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate following normality tests. Odds ratios (OR) are presented as a value and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Patients

During the study period, ERCP was performed in 145 LT patients. From these, 25 patients were excluded due to one of the following reasons: insufficient data, ERCP performed as a diagnostic procedure, previously suspected biliary complication not confirmed by ERCP or patients in on-going treatment. After the application of exclusion criteria, 120 patients submitted to therapeutic ERCP where included in the study.

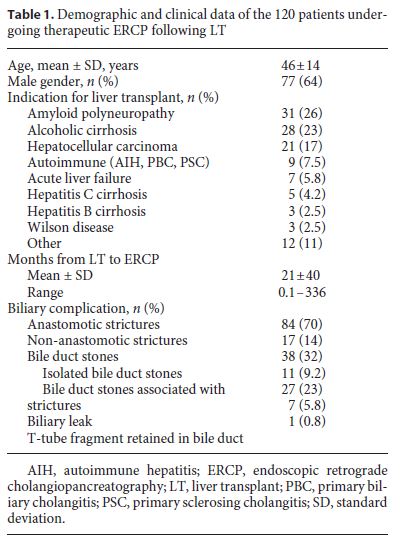

Demographic and clinical data of the 120 patients submitted to therapeutic ERCP are described in Table 1. Mean age was 46 ± 14 years and 64% were male. The most frequent indications for LT were amyloid polyneuropathy in 31 patients, alcoholic cirrhosis in 28, and hepatocellular carcinoma in 21. ERCP was performed following a mean of 21 ± 40 months after LT. Diagnosed biliary complications were as follows: AS in 84 (70%) patients, NAS in 17 (14%), 15 being extrahepatic, BL in 7 (5.8%), and T-tube fragment retained in biliary duct in 1 (0.8%) patient. BDS occurred in 38 (32%) cases: 11 (9.2%) patients had isolated BDS (BDSi), while the remaining 27 (23%) were associated with AS or NAS (BDSs).

Endoscopic Treatment – Description

There was a unique case of a T-tube fragment retained in the bile duct, in which complete endoscopic extraction was not possible. The patient developed a complex stricture and underwent surgery (re-transplantation). Since this was a single case, it was excluded from the remaining statistical analyses.

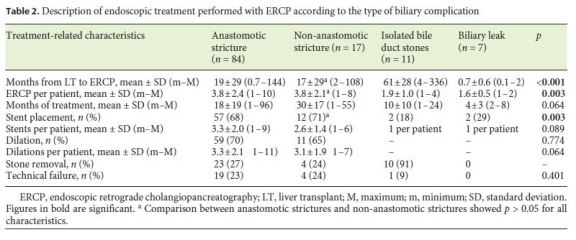

Table 2 relates the characteristics of endoscopic treatment to each complication. The mean time between LT and biliary complication was statistically different between complications ( p < 0.001). BL occurred earlier than AS ( p < 0.001), NAS ( p = 0.012) and BDSi ( p < 0.001), and BDSi occurred following a more prolonged time than AS ( p = 0.036) and NAS ( p = 0.03). There were no statistical differences between presentation of AS and NAS.

Twenty-four cases were classified as a technical failure, in which no treatment was performed, since it was not possible to cannulate the papilla (4 cases) or the desired biliary duct after sphincterotomy (20 cases). There were cases of technical failure in all complications except for BL, with no statistical differences between complications ( p = 0.401).

Multiple ERCP were required in the majority of patients, with 92 (77%) patients requiring more than 1 procedure and 27 (23%) underwent 1 ERCP. The mean number of ERCP per patient was 3.8 ± 2.4 for AS, 3.8 ± 2.1 for NAS, 1.9 ± 1.0 for BDSi, and 1.6 ± 0.5 for BL ( p = 0.003).

Regarding AS, stents were placed in 57 (68%) patients, with a mean of 3.3 ± 2.0 per patient and dilation was performed in 59 (70%), with a mean of 3.3 ± 2.1 per patient. For NAS, stents were placed in 12 (71%) patients, with a mean of 2.6 ± 1.4 per patient and dilation was performed in 11 (65%), with a mean of 3.1 ± 1.9 per patient. From a total of 110 plastic stents, the most common diameters were 8.5 Fr in 38 (35%) stents and 10 Fr in 50 (53%), followed by 11.5 Fr in 7, 7 Fr in 3, 11 Fr in 2 and 9.5 Fr in 1. Stents were removed or replaced after a mean time of 4.5 ± 2.6 months. In 26% of the procedures, 2 simultaneous stents were placed and, in the remaining, 1 single stent was placed. In most procedures, stent placement was preceded by an endoscopic dilation, except in 2 procedures for NAS and in 7 for AS, where only 1 stent was placed. There was a significant proportion of patients with strictures in which BDS were removed: 23 (27%) patients with AS and 4 (24%) with NAS. All BL patients underwent sphincterotomy and in 2 cases a plastic stent was placed. BDSi was extracted with a Dormia basket in 9 patients, an extraction balloon in 5 patients, and mechanical lithotripsy was used in 1 patient.

The duration of treatment was variable: a mean of 18 ± 19 months for AS, 21 ± 17 months for NAS, 10 ± 10 months for BDSi, and 4 ± 3 months for BL, with a tendency to reach statistical significance between complications ( p = 0.064).

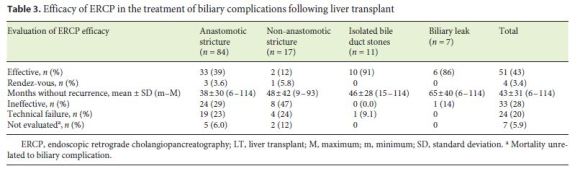

Endoscopic Treatment – Efficacy

Table 3 summarizes ERCP efficacy for each complication. Overall, ERCP was successful in 55 (46%) patients (51 with isolated ERCP and 4 rendez-vous ERCP) and ineffective in 33 (28%) patients. Per complication, efficacy was 39% in AS, 12% in NAS, 91% in BDSi, and 86% in BL. These patients had a mean follow-up time of 43 ± 31 months (range 6–114). In 7 (5.9%) cases, 5 AS and 2 NAS, it was not possible to classify ERCP efficacy due to mortality unrelated to biliary complication. Excluding the cases of technical failure or efficacy not evaluated due to unrelated mortality, ERCP was effective in 36 (60%) patients with AS. Cases of ERCP inefficacy or failure were treated with PTC in 10 patients with AS and 9 with NAS and surgery was performed in 35 patients with AS, 5 with NAS, and 1 with BL.

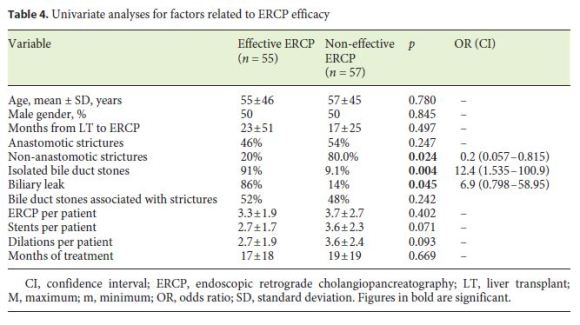

Univariate analyses comparing potential factors associated with effective ERCP versus non-effective ERCP (Table 4) were performed. The effective ERCP group included patients in whom ERCP was the only treatment and also rendez-vous ERCP. The non-effective ERCP group included cases of ERCP inefficacy and cases of technical failure. Cases of premature death were excluded. The presence of NAS was associated with a lower chance of ERCP efficacy (OR = 0.2) and the presence of BDSi or BL with a higher chance of ERCP efficacy (OR for BDSi = 12.4 and OR for BL = 6.9). No statistical significance was found regarding other factors such as age, gender, time of presentation of biliary complication, number of ERCP per patient, number of stents or dilations, BDS associated with strictures, and duration of treatment. A comparison between effective and non-effective ERCP was also performed for each complication and no statistical differences were detected regarding the age, gender, number of ERCP, number of stents, or number of dilations.

Discussion

Management of post-LT biliary complications is complex and requires a multi-disciplinary team involving surgery, hepatology, endoscopy, and interventional radiology [1]. Invasive approaches, such as ERCP or PTC, should be considered as treatment options rather than diagnostic tools [1]. Several papers report ERCP outcomes in the treatment of post-LT patients, with variable percentages of efficacy in different series of patients [1, 9]. Regardless of the reported outcomes, we consider that the knowledge of the experience of each centre is also important, since local expertise and availability are involved in treatment decisions [4].

ERCP efficacy largely depends on the type of complication. Regarding AS, balloon dilation of the stricture is usually performed followed by placement of plastic biliary stents, leading to reported long-term response in 70–100% of patients [3, 4]. Several sessions of ERCP with dilation and stent are frequently required [3]. The number of stents and sessions are not fully defined; however, recent literature suggests exchanging plastic stents every 3 months for the first 9–12 months, placing larger ones or multiple stents, until the resolution of the stricture [4]. Efficacy in this study was lower than that described in most papers, with 40% of all diagnosed AS cases being resolved, although there is one study with similar results [10]. However, if we only analyse the patients in whom a treatment was successfully performed (excluding technical failures and patients that died before an evaluation could be made), ERCP could successfully treat 60%, which is closer to the described efficacy. One factor that might have influenced this result is the long study period, 10 years, with understanding of the best strategy probably increasing over time, leading to the inclusion of patients with heterogeneous treatment regimens. Indeed, the optimal treatment is still under investigation [11]. In recent years, covered self-expandable metal stents (SEMSs) have been increasingly used in this context. A systematic review reported 80–95% of stricture resolution with SEMSs, but with a significant overall migration rate of 16%. Therefore, the evidence does not point to a clear advantage to their use over plastic stents [12]. A non-randomised multicentre study on the management of benign biliary strictures reported a worse clinical outcome of SEMSs in post-LT patients, with 68% stricture resolution compared with overall success (76%) or a chronic pancreatic group (80%) [13]. More recently, a prospective, observational study at a single tertiary care site has also suggested a lack of advantages of SEMSs over plastic stents, with long-term resolution of 61 and 39% recurrence after a 4-year follow-up period [5]. This study raises the question that monitoring patients over a longer period may detect more recurrences, regardless of the type of stenting. Published studies regarding stenting in post-LT strictures have the drawback of a short-term follow-up [14]. Our study includes patients with successfully treated strictures with a long-term follow-up, up to 114 months. Recently, a retrospective study with 56 patients analysed the long-term results of endoscopic management of post- LT AS with plastic stents, reporting a high rate of success and low recurrence, with a median follow-up of 69 months (5.8 years) [14].

Treatment of NAS is technically more difficult than treatment of AS [1]. It includes a set of biliary changes, with different pathogeneses and variations in anatomical location and severity [3]. ERCP is a first-line strategy; however, it is less successful than in AS [3]. The endoscopic approach is similar to that in AS, including balloon dilation of all accessible strictures, placement of plastic stents and extraction of biliary sludge and casts [3, 4]. It is reported that only 50–75% of patients with deceased donor LT have a long-term response to endoscopic therapy [3, 4]. These patients have less favourable overall outcomes, including increased graft loss and up to 50% of patients will require liver re-transplantation [3]. Indeed, these patients showed poorer results in our study, with higher ERCP inefficacy (almost 50%), technical failure (24%), and mortality before the efficacy evaluation could be conducted (12%). However, since the group was small (17 patients), any conclusions should be drawn with caution.

BDS in post-LT patients is associated with multiple risk factors, such as strictures, drug-induced lithogenesis (namely cyclosporine, by inhibiting bile secretion and promoting functional biliary stasis), bacterial infection, ischaemia, biliary reflux, and biliary mucosal inflammation [1, 3, 4]. We report a high percentage of BDS associated with strictures (32% of all patients). Generally, ERCP is very successful in removing BDS, with a reported efficacy around 90–100% [3], similar to our results. It can be hypothesised that the presence of simultaneous complications may make endoscopic procedures difficult, but despite the high prevalence of BDS, our results do not show an association with worse outcomes.

ERCP is the gold standard for the diagnosis and treatment of BL with excellent therapeutic results and a reported efficacy of around 90% [3], which is comparable to that in our study (86%). Treatment usually involves sphincterotomy and placement of a biliary stent for 2 or 3 months or, if the leak is mild (requiring intra-hepatic duct filling to identify the leak), sphincterotomy alone [3, 4, 15]. Sphincterotomy alone was sufficient to treat BL in 4 out of 7 of our patients. In 2011, SEMSs were used in a pilot study of 17 patients with short-term control of leaks, but it resulted in a relatively high stricture rate (47%), leading the authors to conclude that SEMSs cannot be recommended for the management of BL in this setting [16].

Many risk factors for biliary complications following LT have been identified for each complication, including variations in the biliary tract anatomy, method of biliary reconstruction, ischaemic damage to bile duct (hepatic artery complications, warm and cold ischaemia time, bile duct blood supply), immunologic factors, and cytomegalovirus infection, among others. Most of these determinants are related to peri-LT factors [3, 4]. However, almost all factors occur before the patient comes into contact with the gastroenterologist that will perform ERCP. Our results show that the type of complication is an important predictor for ERCP success, since the presence of BDS or BL was associated with a higher chance of success (OR = 12.4 and OR = 6.9, respectively) and the presence of an NAS was associated with a poorer success rate (OR = 0.2). One of the contributions of this study is that it analysed treatment-related factors that could potentially be associated with effective ERCP. Overall, no statistical differences were found in the number of ERCP, duration of treatment, number of stents or dilations, and the presence of BDS requiring extraction between effective and non-effective ERCP. Nevertheless, the heterogeneous and non-standardized treatment choices in this series do not allow a definite conclusion regarding the best strategy.

There are several limitations to our study. As it is a retrospective study, errors regarding data collection are more likely to happen. We tried to overcome this limitation by excluding patients with insufficient data, mainly regarding ERCP procedures and results. Description of biliary complications in ERCP reports can be heterogeneous and sometimes more than one complication may coexist. For example, patients with AS may also have some degree of NAS. This factor may have had some influence on the prevalence of some complications and efficacy evaluation. This limitation was minimised as much as possible by excluding cases with doubtful reports. Another limitation is the small number of patients with complications, mainly BL and NAS, specific of post-LT populations. However, the fact that these data represent 10 years of experience makes it difficult to increase the number of patients. Additionally, this long period of inclusion reflects a significant evolution in the management of these patients. National multi-centre studies could be a major advantage in this setting, allowing for the analysis of a higher number of patients and more homogeneous treatment strategies.

Conclusions

In this series of patients, ERCP had an overall efficacy of 46% in the treatment of post-LT biliary complications. BDS and BL were the complications with better results and NAS presented low rates of successful treatment. The management of biliary complications has evolved in recent years, with greater knowledge of which cases are best suited to endoscopic treatment and which techniques are most appropriate for each complication.

References

1 Macias-Gomez C, Dumonceau JM: Endoscopic management of biliary complications after liver transplantation: an evidence-based review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015;7:606–616. [ Links ]

2 Gastaca M: Biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation: a review of incidence and risk factors. Transplant Proc 2012;44:1545–1549. [ Links ]

3 Atwal T, Pastrana M, Sandhu B: Post-liver transplant biliary complications. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2012;2:81–85. [ Links ]

4 Lisotti A, Fusaroli P, Caletti G: Role of endoscopy in the conservative management of biliary complications after deceased donor liver transplantation. World J Hepatol 2015;7:2927–2932. [ Links ]

5 Tarantino I, Barresi L, Curcio G, Granata A, Ligresti D, Tuzzolino F, Volpes R, Amata M, Traina M: Definitive outcomes of self-expandable metal stents in patients with refractory post-transplant biliary anastomotic stenosis. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:562–565. [ Links ]

6 Rerknimitr R, Sherman S, Fogel EL, Kalayci C, Lumeng L, Chalasani N, Kwo P, Lehman GA: Biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation with choledochocholedochostomy anastomosis: endoscopic findings and results of therapy. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 55: 224–231. [ Links ]

7 Park JS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Lee SS, Han J, Min YI, Hwang S, Park KM, Lee YJ, Lee SG, Sung KB: Efficacy of endoscopic and percutaneous treatments for biliary complications after cadaveric and living donor liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:78–85. [ Links ]

8 Pfau PR, Kochman ML, Lewis JD, Long WB, Lucey MR, Olthoff K, Shaked A, Ginsberg GG: Endoscopic management of postoperative biliary complications in orthotopic liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;52:55–63. [ Links ]

9 Chathadi KV, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, Decker GA, Early DS, Eloubeidi MA, Evans JA, Faulx AL, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley K, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Sharaf R, Shaukat A, Shergill AK, Wang A, Cash BD, DeWitt JM: The role of ERCP in benign diseases of the biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:795–803. [ Links ]

10 Gunawansa N, McCall JL, Holden A, Plank L, Munn SR: Biliary complications following orthotopic liver transplantation: a 10-year audit. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:391–399. [ Links ]

11 Ferreira R, Loureiro R, Nunes N, Santos AA, Maio R, Cravo M, Duarte MA: Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the management of benign biliary strictures: whats new? World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016;8:220–231. [ Links ]

12 Kao D, Zepeda-Gomez S, Tandon P, Bain VG: Managing the post-liver transplantation anastomotic biliary stricture: multiple plastic versus metal stents: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:679–691. [ Links ]

13 Devière J, Nageshwar Reddy D, Puspok A, Ponchon T, Bruno MJ, Bourke MJ, Neuhaus H, Roy A, Gonzalez-Huix Llado F, Barkun AN, Kortan PP, Navarrete C, Peetermans J, Blero D, Lakhtakia S, Dolak W, Lepilliez V, Poley JW, Tringali A, Costamagna G: Successful management of benign biliary strictures with fully covered self-expanding metal stents. Gastroenterology 2014;147:385–395. [ Links ]

14 Tringali A, Barbaro F, Pizzicannella M, Bokoski I, Familiari P, Perri V, Gigante G, Onder G, Hassan C, Lionetti R, Ettorre GM, Costamagna G: Endoscopic management with multiple plastic stents of anastomotic biliary stricture following liver transplantation: longterm results. Endoscopy 2016;48:546–551. [ Links ]

15 Dumonceau JM, Tringali A, Blero D, Devière J, Laugiers R, Heresbach D, Costamagna G: Biliary stenting: Indications, choice of stents and results: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline. Endoscopy 2012;44:277–298. [ Links ]

16 Phillips MS, Bonatti H, Sauer BG, Smith L, Javaid M, Kahaleh M, Schmitt T: Elevated stricture rate following the use of fully covered self-expandable metal biliary stents for biliary leaks following liver transplantation. Endoscopy 2011;43:512–517. [ Links ]

Statement of Ethics

This study did not require informed consent nor review/approval by the appropriate ethics committee.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

* Corresponding author.

Dr. Ana Rita Alves

Serviço de Gastrenterologia, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra

Av. Bissaya Barreto e Praceta Prof. Mota Pinto

PT–3000-075 Coimbra (Portugal)

E-Mail alvess.anarita@gmail.com

Received: October 11, 2016; Accepted after revision: March 20, 2017

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Margarida Marques for her contribution with statistical support.