Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

Share

Portuguese Journal of Public Health

Print version ISSN 2504-3137On-line version ISSN 2504-3145

Port J Public Health vol.35 no.1 Lisboa 2017

REVIEW ARTICLE

Implementing Case Management in Portuguese Mental Health Services: Conceptual Background

Implementação de um Modelo de Gestão de Cuidados nos Serviços de Saúde Mental Portugueses: Base Conceptual

Pedro Mateusa; José M. Caldas de Almeidaa; Álvaro de Carvalhob; Miguel Xaviera

aDepartment of Mental Health, NOVA Medical School, NOVA University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

bNational Programme for Mental Health, Directorate General of Health, Ministry of Health, Lisbon, Portugal

ABSTRACT

Case management implementation processes are one of the best examples on how an evidence-based practice can influence health services organisation. This practice helped shaping mental health teams, increasing their multidisciplinarity and interdisciplinary work in the last decades. Examples from several countries show how effectiveness research blends into health policy development to meet different needs in each health system, thus influencing case management inception and improvement of care. Portugal followed its own path in case management implementation, determined mostly by mental health services organisation and closely linked with the capacity to implement a national mental health policy in the last years.

Keywords: Case management Illness management Mental health Services organisation Implementation

RESUMO

Os processos de implementação de um Modelo de Gestão de Cuidados são um dos melhores exemplos de como uma prática baseada na evidência pode influenciar a organização dos serviços de saúde. Esta prática ajudou a moldar as equipas de saúde mental nas últimas décadas, aumentando a sua multidisciplinaridade e o trabalho interdisciplinar. Os exemplos de vários países mostram como a investigação sobre a efectividade se harmoniza com o desenvolvimento de políticas de saúde para fazer face às diferentes necessidades de cada sistema de saúde, influenciando a implementação da gestão de cuidados e a melhoria de cuidados. Portugal seguiu o seu próprio caminho na implementação da gestão de cuidados, determinado maioritariamente pela organização de serviços associada à capacidade de implementar uma política nacional de saúde mental, nos últimos anos.

Palavras Chave: Gestão de cuidados · Gestão da doença · Saúde mental · Organização de serviços · Implementação

Introduction

Mental disorders are a significant cause of lost years of healthy life and account for 3 of the 10 major causes of burden in low- and middle-income countries, and for 4 of the 10 leading causes of burden in high-income countries. Depression is the second leading cause of years lost due to disability and it will be the leading cause in 2020, while suicides are the largest source of intentional injury in developed countries 1. Well-known burden, impact 2, and costs 3 make mental health a public health priority around the world.

Although severe mental disorders like schizophrenia have a relatively low prevalence, they have a tremendous impact for patients, families, carers, as well as for the society as a whole. In the last years, several commitments have been formed between leading health organisations and countries 4, and official key plans have been published in order to help countries with a roadmap to lead change in the mental healthcare systems 5. Today, all major international mental health guidelines advocate for a public health approach to mental health, with the support from a broad set of organisations and with concerns ranging from the existent treatment gap to the economic impact 6. This public mental health perspective is an added value for millions of people around the world, fostering a continuous improvement of mental health services. The evolution of the social perception of mental illnesses has had a great influence on the organisation of mental health services. The emergence and development of the Case Management Model 7 is certainly one of the best examples of that, allowing us to express the several stages and metamorphoses of this model in the trends of mental healthcare delivery of the last 4 decades.

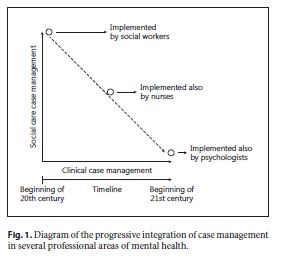

In the beginning of the 1970s, a team of US researchers, comprised of Marx, Stein, and Test, sought to establish a care standard for people with severe mental illnesses that would provide such people with more autonomy, a better quality of life, as well as a lower relapse risk [7 , 8 ]. Their perspective would eventually change the way we view the prognosis of illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, overcoming decades of pessimistic and deterministic perspectives on the “fate” of patients. This paradigm has deeply changed the organisation of mental health services, namely the diversification of the type of care provided, the creation of multidisciplinary teams, and the increase in interdisciplinary functioning. Another clear sign of this change and its intersection with the development of “case management” is how several professional groups increasingly integrated this practice into their own work, thus contributing to its progressive enrichment (Fig. 1).

Case management is defined as a specialised care package to meet the needs of patients with more severe psychiatric impairments, usually defined by either a diagnosis of severe and chronic psychosis or a pattern of high service use 9. It is an intervention characterised by the collaboration between patients and professionals to get the best treatment available, reduce susceptibility to relapses, and cope more effectively with symptoms, within the perspective of recovery. Case management is also a mental health treatment model that provides services in 4 broad areas, including several components in each area: (1) initial phase (engagement, psychological assessment, recovery planning); (2) environmental interventions (linkage with community resources, consultation with families and other caregivers, maintenance and expansion of social networks, collaboration with other health professionals, advocacy); (3) patient interventions (intermittent individual psychotherapy, training in independent living skills, patient psychoeducation); and (4) patient-environmental interventions (crisis intervention, mental health monitoring) 10. The effectiveness of this model has been deeply studied since the earliest stages of its development 7, including a key meta-analysis over the last 20 years of case management use 11 and specific reviews about specialised perspectives of case management implementation 12. These developments will be further analysed below.

The growing focus on the rights of people with disabilities, as well as the change in the expectations and possibilities in terms of pharmacotherapy, strengthened the perceived need of increasing access to services and their integration in the community, naturally leading to the conclusion that services and care would have to leave behind their anachronistic and isolated system 13. Therefore, historically one can say that case management has been a major player in the changing process of mental health policies and services in most Western countries, raising a need to understand its role beyond the concept of evidence-based practice.

In 2006, given the unmet needs identified in the mental health sector throughout the country 14, the Portuguese Government set a taskforce (the National Commission for the Restructuring of Mental Health Services) responsible for preparing a new mental health plan. The National Mental Health Plan 2007–2016 (NMHP) was approved in January 2008 15, following a broadly participated public discussion and involving all major stakeholders related with the mental healthcare sector, from both the public and social sectors, as well as associations of users and families. The National Mental Health Coordination, responsible for the implementation of the newly approved NMHP, defined case management as a priority for mental healthcare delivery and for the organisation of mental health services throughout the country 16, following the recommendations of the most important international health organisations [4 , 5 ].

In this first paper (Conceptual Background), we critically review the implementation of case management in countries with different models of healthcare organisation (including Portugal), focusing on the impact of case management on the organisation of mental health services. This is a non-systematic, narrative-type review, with a focus on the countries where the model was born, developed, and more systematically evaluated (USA, UK, and Australia). A second paper by our group will present the methodology and the outcome of the National Case Management Training Programme implementation in the Portuguese mental health services.

Implementing Case Management: Historical Background

In this section, we describe the main models of case management. We do this by considering the group of countries where case management inception has already occurred, looking at their stage of implementation, and reporting the availability of current research results. A sequential approach addressing the historical background, implementation, and impact dimensions of case management complements its structure.

United States of America

In the USA, the inception of case management dates back to the period between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. In this period, charity organisations were almost exclusively the only groups to provide social care within a poorly coordinated and fragmented system. The first systematic approach to challenge this situation was conducted in 1932 through the “Social Security Act” with 2 important consequences: (i) the recognition of the need for a greater intervention of the federal government in care organisations, (ii) the development of programmes which would later be known as integrated care 17.

Despite the approval of the first “Mental Health Act” in the USA and the consequent creation of the NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health) in 1946, with the support of US President Harry Truman, the coordination of mental healthcare would only see new developments 30 years after the “Social Security Act” with the “Community Mental Health Act” in 1963, which was part of John F. Kennedy’s “New Frontier” programme.

Even overlooking the important contributions of this new piece of legislation (such as the development of community mental health services), its approval additionally led to the creation of countless specialised but more isolated social services. As a consequence of these mixed results, in 1971, the federal government made a critical attempt to relaunch the coordination between health and social services 13 with the following objectives: (a) better services coordination, (b) a holistic approach to the individual and the family, (c) the provision of a comprehensive range of local services, and (d) the reallocation of human resources from hospitals to the community 18. From this point onwards, case management has taken centre stage for 2 main reasons, which were cross-sectional to all levels related to mental health, from the development of policies to care provision. The first of these reasons was closely related to the rapid growth of mental health facilities in the community in the 1960s and 1970s. This led to an exponential increase in accessibility but also to the emergence of several services with almost no coordination. The network of services had a dispersed, fragmented organisation, which was frequently doubled and without inter-coordination. As Test witnessed in 1979, regarding the mental system in the USA, it was frequent to use expressions such as “fragmented system,” “fall through the cracks,” or “get lost in the system.” Within this context, case management represented a unique opportunity to create a mechanism that could ensure patient guidance through the myriad of dispersed services 19. The second reason was the radical shift in the paradigm of care provision, led by the de-institutionalisation process. Before this, most mentally ill people were treated in large psychiatric institutions, which were often overcrowded and inhumane. However, from an inpatient’s care perspective, all services were under the same roof, and thus not dispersed. When mentally ill people began to become de-institutionalised, care responsibilities were transferred to several agencies 19, a state for which there was no map or guide. At the end of the 1970s, given the need to define the structure of mental health services and the rules that could ameliorate the dispersion of services, the NIMH elected case management as a major model of service organisation 13.

The Case Management Model proposed by Stein and Test in Madison profoundly changed the way in which community mental healthcare was viewed. The PACT (Programme for Assertive Community Treatment) was the first structured case management programme directed at people with severe psychiatric conditions with high levels of service use 7. Subsequently, the latest ACT (Assertive Community Treatment) nomenclature was drawn from this concept, becoming a case management model applied by multidisciplinary treatment teams throughout most Western countries 9.

The 1990s were characterised by the emergence of other case management models in the USA, such as the Strengths Model and the Intensive Case Management (ICM) Model. The Strengths Model, which originated in the field of social services, contributed to the development of the recovery concept, since it was based upon premises which contradicted the underestimation of the rehabilitation potential of people with severe mental illnesses and focused on treatment objectives set by the involved people themselves. This approach also recognised that there are resources in the community that must be strengthened, and that people must be provided with follow-up in community environments which focus on individual objectives (strengths) and local resources 20.

The ICM Model was drawn from an adaptation of the traditional Case Management Model, although typically focused on more severe cases, such as higher relapse risk, using patient-to-therapist ratios 3 times lower than those in the traditional model 21. Some authors mention similarities between the ICM and the ACT Models, although the work within a multidisciplinary team is not a requirement to develop the former [12 , 13 , 17 , 22 ]. In 1997, the report of the President’s New Freedom Commission for Mental Health 23 requested the transformation of mental health services, driven by the recovery principle. This principle, which is difficult to define, establishes that beyond the need for clinical and rehabilitation improvement, the treatment of people with severe mental illnesses must help them to achieve considerable levels of quality, satisfaction, and participation in their lives.

The concept of recovery, which has only recently begun to be applied to mental health, has been applied to physical health for a long time and quite frequently. In physical health, recovery is not synonymous with the complete absence of symptoms or suffering, or the complete recovery of abilities. In William Anthony’s example, “a person with paraplegia can recover even though the spinal cord has not” 24. The Commission stated that the recovery framework was crucial to achieve a less hierarchical decision-making process, integrating professionals, patients, and families. On the other side, the Commission also stressed the need to provide the population with evidence-based interventions, drawing attention to the huge gap between evidence and practice in services, caused by shortcomings in implementation 23.

In 1997, as a result of the consensus produced by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Conference where the NIMH and Patient Outcomes Research Team members and researchers were present [18 , 19 , 25 ], the creation of a programme which integrated evidence-based psychosocial treatment was decided, with the objective of helping people to cope with their symptoms and to prevent relapses. The Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) was developed within this context, between 2000 and 2002, as part of the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices project 26. This programme included techniques such as psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioural strategies for drug compliance, relapse prevention planning, social skills training, and the management of refractory psychotic symptoms 10.

Nowadays, the IMR is the case management benchmark in the USA, having influenced several regions throughout the world [7 , 9 , 13 , 19 , 20 , 27 -30 ]. It was also the benchmark for the implementation carried out in Portugal within the context of the NMHP 16.

United Kingdom

In the UK, case management followed quite a different path. Although it can be traced back to the USA, slightly more than two decades later did this practice start gathering focus on implementation. Within this country, where different cultures with strong expressions of their health systems meet, it is important to mention how case management was interpreted in the UK, and how that shaped mental health practices and services organisation.

The concept of case management officially emerged in the UK when the report of the House of Commons Social Services Committee was published in 1985. This document, which recommended the implementation of keyworkers within the scope of community care, was the basis of the report on the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), drafted by Roy Griffiths at the request of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and implemented through the action plan White Paper on Community Care – Caring for People in the Community. This action plan was published in 1990 31, highlighting the importance of the case management approach:

Where an individual’s needs are complex or significant levels of resources are involved, the Government sees considerable merit in nominating a “case manager” to take responsibility for ensuring that individuals’ needs are regularly reviewed, resources are managed effectively and that each service user has a single point of contact 32.

It is precisely in this definition, and in its conceptual redraft only 1 year later, that case management in the UK took a rather different direction from the traditional US clinical model.

This new direction was associated with the definition of the central role of the case manager not as care provider (as in the USA) but as care broker, responsible for assessing people’s needs, drafting a care plan, referring people to suitable specialised services, monitoring and assessing these services while revising the individual care plan, and ensuring that contact is maintained [23 , 24 , 33 -35 ]. With this change in perspective, which generated a new concept of case management, the British Government clearly recommended a brokerage model, instead of the clinical model launched by the ACT in the USA. It is recognised that, unlike in the USA, in the UK mental health teams had already fully integrated components of assertive treatment and care coordination 21. Given the UK political context, the focus was on service efficiency and cost containment strategies and, therefore, the Care Programme Approach (CPA) initiative, the official case management precursor in the UK, was designed without a strong clinical profile.

From an implementation point of view, in 1999, the Mental Health National Service Networks document 36 set a separation between the 2 models: the CPA model, using a case management brokerage approach, and the clinical Case Management Model, based on ACT. This change was brought about by the definition and consequent authorisation to deploy 170 assertive teams in the community 12, with the characteristics of the above-mentioned clinical ACT model [22 , 26 ]. Since then both models have been implemented in the UK, with different results.

Australia

Historically, in Australia, there has been systematic research into alternative community treatment since the beginning of the 1980s [10 , 37 ], and although both brokerage and clinical case management models are still used, the latter is the predominant one 38.

From an implementation point of view, this was a consequence of the influence of Test’s work in Australia, specifically in one group of researchers from Sydney, that provided the setting for the first complete implementation of the “Training in Community Living” programme within a community mental health team outside the USA 39. The conclusions of the randomised controlled trial associated with this implementation process were similar to those reached by the US colleagues, namely better clinical performance, lower rates of compulsory admissions, and effective follow-up after 12 months 40 when compared to the usual treatment by the same teams. These results entailed the use of a clinical Case Management Model implemented in mental health teams, just like in North America 41.

Another important development of case management in Australia was its inclusion, as an essential component, in early intervention in psychosis 42 – a model which benefited from widespread dissemination and world-wide consensus since 2000 43, based upon strong biopsychosocial treatment managed by assertive teams trained in clinical case management.

In Australia, through the dissemination of the Case Management Model, it was possible to ensure important measures related to the deinstitutionalisation process, with a positive impact on the number of admissions, on the accommodation outside the hospital, and on the average dosage of medications 44.

Other European Countries

In Europe, several countries have developed programmes, which use clinical case management as a treatment model for people with severe mental illnesses. Many of these countries present considerable levels of implementation, some with proven evidence such as Sweden 30 and Ireland 45, and others with ongoing studies such as Denmark 46 and the Netherlands 47. All of them, except for the Dutch case, which assesses the effectiveness of a Case Management Model specific to the country, derive from the above-mentioned IMR Model 48. These studies, conducted in similar health systems (tax funded, catchment area model), showed comparable favourable outcomes. However, the assessment of the IMR Model in Europe is far from linear. Based upon the literature available, we believe that the path of effectiveness is difficult to tread, not only because of the differences between the health systems, but also because of the care history and culture in the target countries, and the moment when implementation takes place 27.

The differences within European countries and between those countries and the USA 33 raised very important questions from an implementation point of view; questions that have often been overlooked by comparative studies 49. The poor description of the services given to both the experimental and control groups excludes a substantial part of the organisation’s influence and service culture from the weighting factors used in the statistical regression models.

Italy is a good example for the complex interactions between practice implementation and local culture and values. One of the issues addressed was, ab initio, whether Italy really needed a Case Management Model in the mid 1990s, considering the radical reform in favour of community psychiatry conducted in the late 1970s 50. The initial scepticism raised questions regarding the need to implement case management in Italy, compromising the efforts to provide this service approach with sustainability.

In Germany, a country characterised by a healthcare structure widely influenced by the separation of health and social care, the introduction of case management was considered useful 27. However, a case-control study published in 1992 51 did not show considerable differences from the use of this model in a context where the levels of resources in outpatient care are already high.

In Sweden, the use of case management showed good results, namely regarding the reduction of hospitalisation and the improvement in quality of life. However, there was a clear recommendation that, in that context, the case manager should use a clinical model; thus, professionals working within community multidisciplinary teams would require specific training 52.

In summary, it seems that the differences in the case management implementation throughout Western countries might have been due not only to dissimilarities between services, but also to differences in funding and cultural issues. From the prevention of service fragmentation to the need for cost containment, case management has served the progressive attempt to improve care provided to people with severe mental illnesses, while pacing the transformation of mental health services. The way in which these 2 dimensions determine each other generated countless paths, such as the ones mentioned above.

Effectiveness of the Model

One of the main difficulties when addressing the scientific landscape of the Case Management Model is the variety of aspects of its implementation and application, resulting from widespread proliferation and successive cultural adaptations. The latter are clearly influenced by contextual needs and constraints, namely policies, health systems, and professional cultures.

Another aspect concerns the evolution of what is considered case management. Some authors advise that the current review of the model’s effectiveness, mainly comparative studies, must take into consideration the transformation of what today is the standard case management. For 30 years, this standard has been refined and is now much closer to what was previously called specialised case management 53. One of the conclusions which can be drawn from the latest studies 54, clarifying an increasingly smaller difference between specialised case management and usual treatment, is that, by its more optimistic perspective, the growing evidence regarding the benefit of using this practice led to the progressive integration of its ingredients into the usual treatment provided by mental health teams, and that the differences, namely those raised by review publications, comprise a contribution to the improvement of care provision and an opportunity for future research 55.

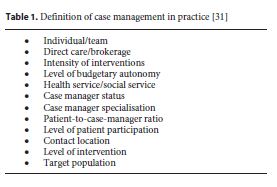

Already in the beginning of the broad development of case management, several authors mentioned, from a clinical point of view, the need to use essential ingredients in the development of effective models as opposed to copying models imported from other countries [22 , 31 ]. Thornicroft et al. proposed an interpretation of several models in light of 12 axes (Table 1), which would classify this practice into several categories 31. Conversely, Bond et al. 22 proposed the identification of fundamental ingredients to guarantee effectiveness, which resulted in an improvement of the care derived from the most assertive case management model (ACT), with dozens of studies proving its effectiveness. This effectiveness would be felt in the decrease in hospitalisation days, increase in accommodation stability, and improvement in symptoms and quality of life, with special success in patient’s involvement in the treatment. However, these ingredients have demanding requirements in terms of service operation, including multidisciplinary teams, service integration, low patient-to-therapist ratio, contact location in the community, focus on everyday problems, rapid access with an assertive spirit, individualised services, and absence of time limit for follow-up 22. This practice showed benefits for people with severe mental illnesses [7 , 39 ] in the above-mentioned areas since its implementation.

In this context, it is relevant to highlight 2 important reviews. Kim Mueser et al. 9 reviewed 75 studies related to case management implementation using several methodological designs (pre-post, quasi-experimental, and randomised controlled). The model showed effectiveness in the following dimensions: accommodation stability, hospitalisation time, symptom severity, and substance abuse. Additionally, a result analysis was proposed for more subjective aspects such as social integration and quality of life 9. The review 9 showed consistent results in the decrease in hospitalisation time and in naturally associated aspects such as accommodation stability and autonomy, found in 75% of the controlled studies. Other important findings included an improvement in symptoms, with a significant decrease in severity in 50% of the studies included in the review. The results related to compliance with medication were inconclusive, probably due to the reduced number of studies at the time. There was no consistent benefit for social integration and vocational success. Regarding the above-mentioned subjective aspects, case management had a moderate effect on the increase in both quality of life and level of service satisfaction of patients and their relatives 9.

In a meta-analysis of 20 years of case management practice, which included 44 controlled trials, Ziguras and Stuart 11 presented results similar to those of the 1998 review, showing that this model had clear advantages in comparison with the usual treatment. Additional results revealed a decrease in family burden and cost of care. It was also possible to show an improvement in social functioning and a decrease in the rates of treatment abandonment. The results of this study were equally important to clarify one of the conclusions of the review made for Cochrane Collaboration by Marshall and Lockwood 56, regarding the apparently negative fact that case management increased hospital admissions. Despite the confirmation of this result through the meta-analysis, it was shown that hospitalisation was shorter; thus, the total number of hospitalisation days was lower. The 2 Cochrane reviews [56 , 57 ], meanwhile removed from the database, and the results of 2 large studies on case management in England (UK700 and PRiSM), confirmed the divergence between the clinical model and the brokerage model, and the relative permissiveness in the association of the two, namely regarding effectiveness [49 , 58 ]. The first 59 compared ICM with usual treatment, and the second 60 compared 2 models of mental health services organisation. In the absence of a randomised controlled trial which studied the ACT clinical Case Management Model, the previous conclusions determined the association of clinical case management with CPA, and the different path followed by the UK in the use of this model, as previously described.

The different ways case management has been implemented throughout the Western countries, leading sometimes to contradictory results, highlight the need to develop adequate methods of assessment.

Case Management in Portugal – First Steps

The implementation of case management in Portugal might be chronologically divided into 2 phases: the first phase is directly related to a non-systematic development of the model in some Lisbon mental health services; the second, initiated in 2008, is related to the governmental decision of implementing case management in all public mental health services following a structured program, under the auspices of the NMHP.

Theoretically, the Portuguese mental health system meets all of the requirements needed to implement a Case Management Model in the public psychiatric services, given that: (i) there is a national health service funded by taxes, with national coverage, regional management, and primary and secondary healthcare networks organised in local services; and (ii) there are also mental health teams in general hospitals, which, in the beginning of 2000, started to implement pilot programmes using some components of case management models.

The most systematic approach to case management in Portugal began with a group of professionals interested in the Early Intervention in Psychosis programmes 61, namely through the International Early Psychosis Association (IEPA) 62. IEPA was internationally launched at the 2nd International Early Psychosis Conference, in New York, in 2002, after a kick-off meeting in Melbourne in 2000, promoted by the Early Prevention Psychosis Intervention Centre (EPPIC).

Following the initiative of the Portuguese members of IEPA, including one of the authors (P.M.), contacts were made to hold a workshop in Lisbon debating early intervention and the use of case management models for people with severe mental illnesses. This workshop took place in March 2002, with the participation of experts involved in case management implementation processes around the world (Jane Edwards in Australia, Paddy Power in the UK, and Paul Amminger in Austria), mental health professionals, researchers, and directors of Portuguese mental health services.

This meeting brought together a group of Portuguese professionals from several mental health services who joined efforts to create the Espiral – Psychosis Study Group, representing the will to implement an early intervention in psychosis approach with a case management model, aiming:

- to train case managers,

- to promote the spread of this model in Portugal,

- and to participate in research conducted by EPPIC (randomised controlled trials).

This group had the advantage to include professionals from 6 public hospitals (Miguel Bombarda, São Francisco Xavier, Santa Maria, Júlio de Matos, Santarém, and Fernando da Fonseca) and also researchers from both Lisbon medical schools. Created in 2003, Espiral set the definitions of the Portuguese wording for the concepts of a case management model (in Portuguese, Modelo de Gestão de Cuidados) and a case manager (in Portuguese, Terapeuta de Referência). The case management model implemented in the Portuguese public mental health services was influenced by the evidence-based clinical Case Management Model [11 , 22 , 38 , 63 ]. Under this model, the case manager is a full member of the multidisciplinary clinical team, responsible for the implementation of an individual care plan 63.

To start the programme in Portugal, 2 therapists were trained at EPPIC in Melbourne, who afterwards participated in the joint training of a group of professionals from several hospitals in the region of Lisbon, along with the participation of staff members from the Australian research centre. This group of professionals would later participate in a randomised controlled trial (Euphrosia), promoting the use of this model at several scientific meetings and presenting the first results in 2008 64. In 2008, several hospitals in the Lisbon area had already implemented case management in their practices (Miguel Bombarda, Fernando da Fonseca, São Francisco Xavier, and Santa Maria). In the Hospital de Santa Maria, the professionals, who would kick off the development of rehabilitation units, were trained as case managers promoted by the National Coordination for Mental Health and were involved in the subsequent training for trainers in 2009 and 2010.

Case management has been included as a goal of the NMHP 16. The development of this model is connected to 2 important moments, which legitimate its use. The first moment was the National Meeting on Community Mental Health Teams promoted by the Portuguese Ministry of Health in 2009, where the discussion involving the representatives of public and private services led to the publication of a consensus document on: (1) setting up community mental health teams, (2) individual and shared skills of each professional area, and (3) the definition of a case manager’s role, according with the following recommendations 65:

The Case Manager (CM) must

(a) Be the interface between community mental health teams, the patient and family/friends.

(b) Centralise information (always compiled in a single clinical file).

(c) Design, along with patients and, whenever possible, the family, a care plan, which is presented in team meetings.

(d) Monitor the patients’ care path and evolution over time.

(e) Identify, at each moment, problems and needs.

(f) Refer patients, in team meetings, to professionals whose specific skills better suit an intervention which meets the problems and/or needs identified.

(g) Any of the Team’s professionals may be the CM. To perform CM duties, it is indispensable to have prior training and skills, which allow the professional to recognise the most important psychopathologies in terms of severe mental illnesses.

The second moment was the preparation of the Case Manager’s National Training Programme, as part of the NMHP. The results of the implementation effectiveness of this programme are to be presented in another paper.

Discussion

Case management is a model developed and implemented mostly in English-speaking countries, which led to structural changes in mental health services, with a significant positive impact on people with severe mental illnesses and their families. During the last decades, this model developed along different paths (in different countries), regarding both conceptual and evaluative dimensions. Recent assessment issues on previously ignored areas, such as patient’s perceptions about the illness, employment, and contact with families, have had a strong impact on the transformation of the original model. These changes turned what was known as standard care into standard case management, and what was known as standard case management into ACT. Moreover, it displaced the scientific challenge from treatment effectiveness to implementation effectiveness, as shown in the examples below.

In Australia, the “facsimile” implementation of the American model, brought about by one of the original researchers (Test), led to similar implementation and clinical results.

In the UK, the two-stage implementation process (brokerage followed by a clinical model), generated 2 completely different components of care that converged progressively through the years and today work coordinated.

In the USA, after a long history of success in the use of the clinical model, new challenges required a different approach. In order to overcome these, the IMR Model attempted to address not only clinical effectiveness, but also the problems regarding implementation. Given these reasons, it was developed within the scope of a National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Programme 48.

In Portugal, the first steps of case management began with the implementation of isolated programmes for early psychosis, and only recently the first publications on the use of this model in Portugal began to emerge 16. Several models were then identified and considered as good candidates to consolidate case management in Portugal: albeit positive strengths from every model, this analysis led us to choose the IMR Model as the one to be implemented in Portugal, under the auspices of the National Coordination for Mental Health (Ministry of Health).

Conclusions

From a review of the literature, we can conclude that several dimensions contributed to the way case management was implemented in different countries and impacted different systems of care, and we learned important lessons for the implementation in Portugal. These include the influence from public and private health systems, the use of clinical or brokerage models, and the need to have the support from mental health policies and programmes, namely under a public health perspective. The IMR Model was chosen due to not only its proven effectiveness but also because it considers, in a systematic way, the challenges associated with local adaptation and implementation. This inception process, including the local adaptation methodology and the implementation plan, was developed through a National Case Management Training Programme, and will be described in detail, along with the implementation results, in another paper of this series.

References

1 World Health Organization: The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva, WHO, 2008. [ Links ]

2 Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al: Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013; 382:1575–1586.10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-623993280

3 Balak N, Elmaci I: Costs of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2007; 14:e9.10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01570.x17250716 [ Links ]

4 WHO Europe: Mental Health Declaration for Europe. Geneva, WHO, 2005. [ Links ]

5 European Commission: Green Paper: Improving the Mental Health of the Population: Towards a Strategy on Mental Health for the European Union. Brussels, EC, 2005. [ Links ]

6 Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, et al: Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3:415–424.10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-427083119

7 Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. Conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 31; 37:392–397.10.1001/archpsyc.1980.017801700340037362425

8 Dixon L: Assertive community treatment: twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51:759–765.10.1176/appi.ps.51.6.75910828107

9 Mueser K, Bond G, Drake R, Resnick SG: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:37–74.10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a0333149502546

10 Mueser K, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, et al: Illness management and recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:1272–1284.10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.127212364675

11 Ziguras S, Stuart G: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51:1410–1421.10.1136/bmj.39251.599259.5517631513

12 Burns T, Catty J, Dash M, Roberts C, Lockwood A, Marshall M: Use of intensive case management to reduce time in hospital in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-regression. BMJ 2007; 335: 336–336.

13 McAnally PL, Linz MH, Wieck C; Case Management: Historical Current & Future Perspectives. Cambridge, Brookline Books, 1989.

14 Caldas de Almeida J, Leuchner A, Duarte H, et al: Proposta de plano de acção para a restruturação e desenvolvimento dos serviços de saúde mental em Portugal. Lisbon, Mental CNPAS, Ministério da Saúde, 2007. [ Links ]

15 Ministério da Saúde: Plano Nacional de Saúde Mental 2007–2016: resumo executivo. Lisbon, Ministério da Saúde, 2008.

16 Mateus P, Xavier M, Caldas de Almeida J: Implementing a national case-management training program in Portugal. Eur Psychiatry 2011; 26(suppl 1):555. [ Links ]

17 Rice RM: A cautionary view of allied services delivery. Soc Casework 1977; 58:229–235.

18 Richardson E: Interdepartmental Memorandum: Services Integration in Hew: An Initial Report. Washington, Welfare DOHEA, 1977. [ Links ]

19 Intagliata JJ: Improving the quality of community care for the chronically mentally disabled: the role of case management. Schizophr Bull 1982; 8:655–674.10.1093/schbul/8.4.6557178854

20 Simpson A, Miller C, Bowers L: Case management models and the care programme approach: how to make the CPA effective and credible. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2003; 10:472–483.10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00640.x12887640

21 Burns TT, Creed FF, Fahy TT, Thompson SS, Tyrer PP, White II: Intensive versus standard case management for severe psychotic illness: a randomised trial. Lancet 1999; 353:2185–2189.10.1016/S0140-6736(98)12191-810392982

22 Bond G, Drake R, Mueser K, Latimer E: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Dis Manag Health Out 2001; 9:141–159.

23 Hogan MF: New Freedom Commission Report: The President’s New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:1467–1474.10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.146714600303

24 Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1993; 16:11–23.

25 Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:11–20; discussion 20–32.10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a0333039502543

26 Drake RE, Bond GR, Essock SM: Implementing evidence-based practices for people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2009; 35:704–713.10.1093/schbul/sbp04119491315

27 Burns T, Fioritti A, Holloway F, Malm U, Rössler W: Case management and assertive community treatment in Europe. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:631–636.10.1176/appi.ps.52.5.63111331797

28 Hasson-Ohayon I, Roe D, Kravetz S: A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of the illness management and recovery program. Psychiatr Serv 2007; 58:1461–1466.10.1176/appi.ps.58.11.146117978257

29 Levitt AJ, Mueser K, Degenova J, et al: Randomized controlled trial of illness management and recovery in multiple-unit supportive housing. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60:1629–1636.10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.162919952153

30 Fardig R, Lewander T, Melin L, Folke F, Fredriksson A: A randomized controlled trial of the illness management and recovery program for persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2011; 62:606–612.10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_060621632728

31 Thornicroft G, Ward P, James S: Countdown to Community Care: care management and mental health. BMJ 1993; 306:768–771.

32 Langan M: Community care in the 1990s: the community care White Paper: “Caring for People.” Crit Soc Pol 1990; 10:58–70.10.1177/026101839001002904

33 Holloway F, Oliver N, Collins E, Carson J: Case management: a critical review of the outcome literature. Eur Psychiatry 1995; 10:113–128.10.1016/0767-399X(96)80101-519698326

34 Wolfe J, Gournay K, Norman S, Ramnoruth D: Care programme approach: evaluation of its implementation in an inner London service. Clin Eff Nurs 1997; 1:85–90.10.1016/S1361-9004(06)80008-7

35 Marlowe MJ, White C, White KJ: Mental health needs of populations and the burden of secondary care: an audit of patients assessed under the Care Programme Approach in South East Kent. J Mental Health 1999; 8:533–538.10.1080/09638239917229

36 UK National Health Service: National Service Framework for Mental Health: Modern Standards and Service Models. London, NHS, 1999. [ Links ]

37 Hoult J, Rosen A, Reynolds I: Community orientated treatment compared to psychiatric hospital orientated treatment. Soc Sci Med 1984; 18:1005–1010.10.1016/0277-9536(84)90272-76740335

38 Rosen A, Teesson M: Does case management work? The evidence and the abuse of evidence-based medicine. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2001; 35:731–746.10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00956.x11990883

39 Hoult J, Reynolds I, Charbonneau-Powis M, Weekes P, Briggs J: Psychiatric hospital versus community treatment: the results of a randomised trial. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1983; 17: 160–167.10.3109/000486783091600006578788

40 Issakidis C, Sanderson K, Teesson M, Johnston S, Buhrich N: Intensive case management in Australia: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 99:360–367.10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb07242.x10353452

41 Deci PA: Dissemination of assertive community treatment programs. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:676–678.7552557

42 Early Psychosis Prevention & Intervention Centre: Case Management in Early Psychosis: A Handbook. Parkville, EPPIC, 2001.

43 Bertolote J, McGorry P: Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: consensus statement. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2005; 187:s116–s119.16055800

44 Hambridge JA, Rosen A: Assertive community treatment for the seriously mentally ill in suburban Sydney: a programme description and evaluation. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1994; 28:438–445.10.3109/000486794090758717893238

45 O’Brien S, McFarland J, Kealy B, et al: A randomized-controlled trial of intensive case management emphasizing the recovery model among patients with severe and enduring mental illness. Ir J Med Sci 2012; 181:301–308.10.1007/s11845-011-0795-022218933

46 Dalum HS, Korsbek L, Mikkelsen JH, et al: Illness management and recovery (IMR) in Danish community mental health centres. Trials 2011; 12:195.10.1186/1745-6215-12-19521849024 [ Links ]

47 Wynia K, Annema C, Nissen H, De Keyser J, Middel B: Design of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) on the effectiveness of a Dutch patient advocacy case management intervention among severely disabled multiple sclerosis patients. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 10:142.10.1186/1472-6963-10-14220507600 [ Links ]

48 Mueser K: The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32(suppl 1):S32–S43.10.1093/schbul/sbl02216899534

49 Burns T: Case management: two nations still divided. Psychiatr Serv 1996; 47:793–793.10.1176/ps.47.8.7938837147

50 Fioritti AA, Lo Russo LL, Melega VV: Reform said or done? The case of Emilia-Romagna within the Italian psychiatric context. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:94–98.8988965

51 Rössler W, Löffler W, Fätkenheuer B, Riecher-Rössler A: Does case management reduce the rehospitalization rate? Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 86:445–449.10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03295.x1471537

52 Aberg-Wistedt AA, Cressell TT, Lidberg YY, Liljenberg BB, Osby UU: Two-year outcome of team-based intensive case management for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:1263–1266.8590112

53 Smith L, Newton R: Systematic review of case management. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2007; 41:2–9.10.1080/0004867070137110017464675

54 Essock SM, Mueser K, Drake R, et al: Comparison of ACT and standard case management for delivering integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57:185–196.10.1176/appi.ps.57.2.18516452695

55 Burns T: Models of community treatments in schizophrenia: do they travel? Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2000; 11–14.11261633

56 Marshall M, Lockwood A: Assertive Community Treatment for People with Severe Mental Disorders. Chichester, Wiley, 1996. [ Links ]

57 Marshall M, Lockwood A: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000; CD001089.10.1002/14651858.CD00108910796415 [ Links ]

58 Burns T: Care management: case management confers substantial benefits. BMJ 1996; 312:1540.8646163 [ Links ]

59 Holloway F, Carson J: Intensive case management for the severely mentally ill. Controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172:19–22.10.1192/bjp.172.1.199534826

60 Byford S, Fiander M, Torgerson DJ, Barber JA, Thompson SG, Burns T: Cost-effectiveness of intensive v. standard case management for severe psychotic illness: UK700 case management trial. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176: 537–543.10974959

61 Edwards J, McGorry PD: Implementing Early Intervention in Psychosis. Boca Raton, CRC, 2002. [ Links ]

62 McGorry PD, Yung AR: Early intervention in psychosis: an overdue reform. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003; 37:393–398.10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01192.x12873322

63 Thornicroft G: The concept of case management for long-term mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry 2009; 3:125–132.10.3109/09540269109067527

64 Santos L, Gago J, Levy P, et al: Cognitive-behavioural case management in first-episode schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders: the Portuguese experience. Early Interv Psychiatry 2008; 2:A1–A23.

65Coordenação Nacional para a Saúde Mental: Equipas de Saúde Mental Comunitária: Encontro da Curia. Lisbon, CNSM, Ministério da Saúde, 2008 [ Links ]

Received: March 18, 2015

Accepted: December 7, 2016