Introduction

Non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) are probably one of the most serious public health problems in Portugal. In 2015, cardiovascular diseases represented approximately 29.7% of all deaths [1], diabetes affected approximately 10% of the Portuguese population, and the prevalence of high blood pressure was approximately 36% [2]. Obesity, as a chronic disease and a risk factor for developing other NCDs, affects more than 20% of Portuguese adults, together with overweight which affects more than 50% of the population [2,3]. Prevalence of childhood overweight (including obesity) is also high, estimated at 29.6% in 2019 [4]. The increasing prevalence of overweight co-exists with undernutrition. High energy intake is often associated with an insufficient intake of certain nutrients [5].

Approximately 86% of the total burden of disease can be attributed to NCDs, and inadequate dietary habits are among the main modifiable risk factors. In Portugal, data from the Global Burden Disease Study showed that inadequate dietary habits are responsible for approximately 9% of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs; 300,000 DALYs) and represent the leading modifiable risk factor for mortality [1,6,7].

High prevalence of NCDs also has a significant economic and social impact, their treatment places a heavy burden on healthcare costs, and they are also responsible for important productivity losses [8]. According to the report “The Heavy Burden of Obesity - The Economics of Prevention,” by Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [9], in Portugal, 10% of the total healthcare cost is used for the treatment of diseases related to overweight, a percentage which is higher than the average for the OECD countries (8.4%), and which represents 3% of the Gross Domestic Product. According to the same report, it is estimated that, between 2020 and 2050, overweight and its related diseases, may contribute to a decrease in the average life expectancy of approximately 2.2 years [9]. Socioeconomic gradient in NCDs is also observed, and they are more prevalent among underprivileged social classes, and those with lower levels of education. In Portugal, the data from the last National Health Survey [2], suggests that the prevalence of diabetes and high blood pressure is approximately double in individuals with a lower level of education (diabetes: 12.2% in individuals with 4 or more years of schooling vs. 6.4% in individuals with 12 or more years of schooling; high blood pressure: 45.1% in individuals with 4 or more years of schooling vs. 25.6% in individuals with 12 or more years of schooling) [2]. This social gradient also affects the prevalence of obesity (38.5% in individuals with 4 or more years of schooling vs. 13.2% in individuals with 12 or more years of schooling) [3].

The increasing burden of NCDs, an increase in health inequities and the associated reduced productivity in low-income populations created pressure for a stronger policy response on food and nutrition. The objective was to avoid chronic poverty situations where illness and economic disability perpetuate each other among large groups of the population. Today, we are aware that these situations of social vulnerability associated with diet and NCDs are not reversible without intersectoral interventions which may enable an improvement in citizens’ skills and ability to choose healthier food options through modifications at the environment level.

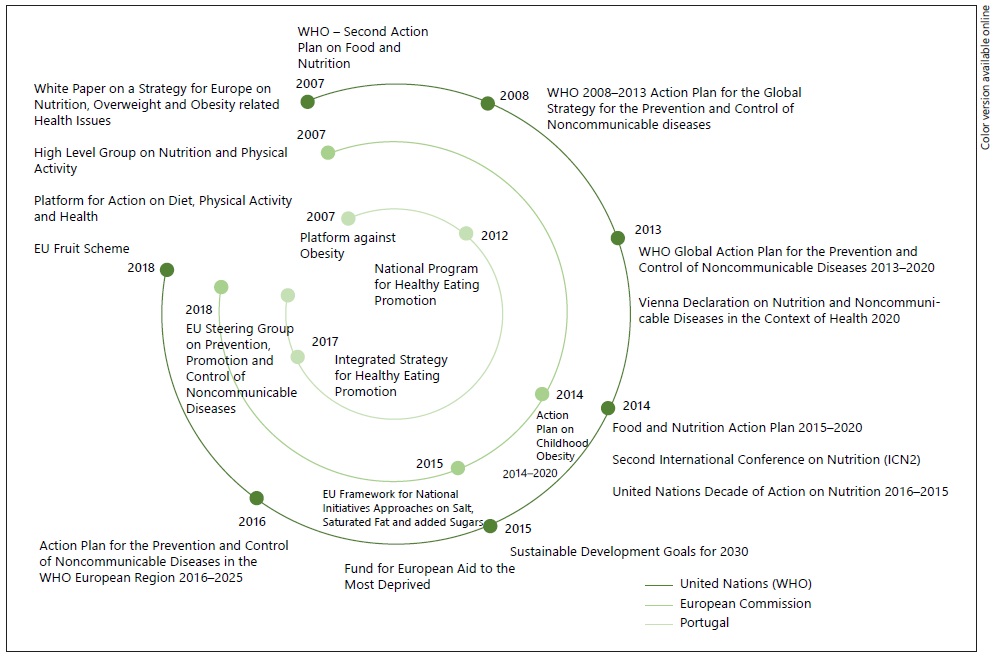

It was in this landscape that a national food and nutrition policy, as a set of concerted measures for improving dietary habits of the population, its nutritional status and health, was recently implemented in Portugal [10]. These integrated, intersectoral food and nutrition strategies have multiplied in the last decade, namely with the creation of the National Program for the Promotion of Healthy Eating (PNPAS) in 2012, and the Integrated Strategy for the Promotion of Healthy Eating (EIPAS) in 2017.

This paper aims to produce an in-depth description and critical analysis of the Portuguese strategies with regard to food and nutrition since their implementation between 2010 and 2020. We further aim to analyze the way in which these strategies are responding to the orientations and priorities established at an international level, namely by the European Commission (EC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Methodology

This paper describes Portuguese public policies on food and nutrition for NCDs prevention throughout the last decade (2010-2020), their main strategic documents, the measures implemented and the results achieved. Taking into consideration the strong link between national policies in this area, and the international agenda of the United Nations and the EC, a short description of the international context was also provided in this paper. This analysis focuses on the last decade (2010-2020), which reflects the period with formal strategies implemented, namely the Platform against Obesity (2007-2011), the PNPAS (2012-present) and the EIPAS (2017-present). For this analysis, documents and legislation produced under the scope of these 3 strategies were considered.

Results

International Strategies for the Promotion of a Healthy Diet. At the international level, strategies for the promotion of healthy diet are well represented in the action plans for prevention and control of NCDs. During the period analyzed in this paper, several strategic documents were published, both by the WHO and the EC, and several policy commitments were adopted, with the aim of strengthening the steps for preventing and controlling NCDs. These guidelines, and their adaptation within the national context, were taken into consideration for the design of the national food and nutrition strategy.

1.Nutrition in the united nations agenda

Nutrition is well represented in the agenda of the United Nations, particularly in its “Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),” published in 2015. In the SDGs, the promotion of a healthy diet, as well as the prevention of NCDs, were considered priorities, namely in SDG 2 - “Eradicate hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture” and in SDG 3 - “Guarantee access to quality healthcare and promote well-being for everyone, of all ages.” Reduction of chronic diseases is a goal of the SDG related to health and well-being (SDG 3) - SDG 3.4 - “By 2030, reduce by one third, premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment, and promote mental health and well-being.” Moreover, healthy eating promotion is one of the proposed strategies.

Twenty years after the first conference in 1992, the United Nations commitment for action on nutrition was reinforced, in November 2014, with the Second International Conference on Nutrition (ICN2). During this conference, the “Rome Declaration on Nutrition and Framework for Action for eliminating hunger and malnutrition once and for all” was endorsed by participating governments [11], and the period from 2016 to 2025 was declared as the decade for action in the field of nutrition - “United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016-2025” - with the goal of intensifying action plans to eradicate hunger and end all forms of malnutrition, assuring an universal access to a healthier and more sustainable diet [12].

Furthermore, during the period under analysis, particularly the years 2011, 2014 and 2018, the first three “United Nations High Level Meetings on Noncommunicable Diseases” took place, and the fight against NCDs was established as a policy priority. Hence, 2011 thereby marks the first Political Declaration of the United Nations for Prevention and Control of Chronic Diseases [13], which recognizes the need to reduce risk factors for NCDs, namely unhealthy dietary habits, particularly by creating healthy food environments. From the three United Nations declarations, the following highlights stood out: (1) recognition of the significant impact of NCDs on children, particularly the rising levels of childhood obesity; (2) need for an intervention based on “health in all policies” principle; (3) importance of implementing legislative and regulatory measures, including fiscal ones, to reduce NCD risk factors, (amongst them, people’s diets); (4) importance of implementing cost-effective and evidence-based interventions to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity, particularly childhood obesity; (5) need for a greater investment in research in the field of public health in order to identify cost-effective prevention measures and, in addition, (6) importance of empowering individuals to make informed choices by promoting health literacy and education through campaigns to promote a healthy diet [13, 14, 15]. These guiding principles are all inscribed in the Portuguese food and nutrition policy, as stated below.

2. WHO strategies in the field of diet and nutrition

Since 2002, WHO Europe has been introducing specific action plans in the field of nutrition. When comparing the first WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policies, with the second (WHO European Region 2007-2012) the main concern was given to NCDs, especially obesity, with the food safety question seeming to lose some of its previous importance [16,17]. Additionally, in response to the new health challenges, in 2008, the WHO also developed an action plan for NCDs - WHO 2008-2013 - Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases, where an unhealthy diet was presented as one of the 4 main NCDs risk factors [18]. Subsequently, this action plan was replaced by the WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013-2020, where the need for national nutrition policies was advocated. In this action plan, to achieve by 2020, 3 out of 9 NCDs global targets depend on implemented actions on food and nutrition: (a) reduce by 30% the intake of salt/sodium (b) halt the rise in diabetes and obesity, and (c) reduce by 25% the prevalence in high blood pressure [19]. Aligned with this global action plan, in 2016 the WHO European Region specifically developed and published Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region 2016-2025 [20]. Previously, in 2013, the Vienna Declaration on Nutrition and Noncommunicable Diseases in the Context of Health 2020 [21] had reaffirmed the political commitment of the Member States in recognizing that a healthy diet can contribute to achieving the objectives defined in the context of the WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013-2020, namely the 25% reduction in the premature mortality associated with NCDs by 2025. In this Declaration, the need to publish a new action plan for food and nutrition policies for the WHO’s European Region was also expressly stated and was launched the following year (2014) as the - European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015-2020 [22]. This action plan emphasizes the need to implement strategies based on the principles of “health in all policies” and of “whole-of-government” and adopts the 5 objectives approved in the Vienna Declaration on Nutrition and Noncommunicable Diseases.

3. Progress of the EC with regard to strategies on diet and nutrition during the period 2010 to 2020

In 2007, 10 years after the creation of the Directorate-General for Health and Consumer Protection (DG SANCO), the first European strategy on food and nutrition emerged, with the publication of the White Book, “A Strategy for Europe on Nutrition, Overweight and Obesity-related Health Issues” [23]. This strategy was a response to the commitment of the European Union to adopt the European Charter for Counteracting Obesity [16]. The main objective was to “establish an integrated EU approach to contribute to reducing ill health due to poor nutrition, overweight and obesity” [23]. In the same year, the High Level Group on Nutrition and Physical Activity was also constituted, and the EU Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health was created to support the implementation of this strategy. The High Level Group on Nutrition and Physical Activity is composed of the 28 Member States representatives, as well as representatives from Norway, Switzerland, Iceland and the WHO. This group’s mission is to share and debate intervention and best practice strategies, with the aim of reducing risk factors for NCDs and encourage the development of European policies in the field of nutrition and physical activity [24]. In 2005, to promote civil society engagement, the EU Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health had already been established, in which approximately 33 European associations are represented, particularly food industry and public health non-governmental associations, scientific and professional societies and consumer organizations.

During 2008-2015, and among the context of the High Level Group on Nutrition and Physical Activity activities, it is worth highlighting the encouragement and support offered to Member States in the implementation of initiatives for reformulating food products (EU Framework for National Initiative Approaches on salt, saturated fat, and added sugars) [25, 26, 27]. Following up on this, the EC has been monitoring the efforts of different countries, which may be found compiled in the report “Sugar content in selected foods in the EU: a 2015 baseline to monitor sugars reduction progress” [28].

In 2014, the political recognition that childhood obesity should be more represented in the EC health political agenda was reinforced by publishing the Action Plan on Childhood Obesity 2014-2020 [29]. This made the fight against childhood obesity a priority, and in a follow-up meeting during the Irish Presidency that took place between Health Ministers of the different Member States childhood obesity was the main topic of discussion. This way, the EC supported the proposal of the Irish Presidency by requesting the development of an EU childhood obesity action plan by the EU High Level Group on Nutrition and Physical Activity. The main areas of intervention were aligned with the White Book on “A strategy for Europe on Nutrition, Overweight and Obesity-related Health Issues,” highlighting the promotion of healthy food environments in schools and the restriction of food advertising to children [30]. Within the framework of this strategy, in 2017 the document “Public Procurement of Food for Health - Technical report on the school setting” was published by the EC [30].

Therefore, a more intensive/structured food and nutrition investment by the EC started in 2007, because before that, and in its first years of existence, the then, DG SANTE essentially focused on questions of food hygiene and safety, and their risks. This first area of interest was brought to as the result of the food crises of the 90s, such as BSE in 1996. During this period, the guarantee of food safety was one of the Commission’s political priorities. In 2000, the White Book on Food Safety was published; one of its main measures was the creation of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2002 [31].

At the same time, other EC policies, particularly in the agriculture sector, are also extremely relevant as far as the promotion of a healthy diet is concerned. In fact, the concept of “health in all policies” was expressly taken up in No. 152 of Maastricht Treaty revision in 1998, in Amsterdam - “health protection shall be assured in the definition and implementation of all Community policies and activities.” Indeed, several strategic EU documents on nutrition and obesity reflect on the impact of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) on the availability of healthy food, suggesting the huge need for considering public health objectives within the designing of the CAP strategy. And as such, it was only at the beginning of 2007, that the first effective consensus between the competing interests of CAP and public health seemed to arise. Interestingly, the reform of the sector of fruit and vegetables within the Common Organisation of the Markets (CMO), which also occurred in 2007, suggests this. For this reason, the European Union, presented a series of proposals: (a) promote fruit and vegetable consumption by children through the distribution of surplus to schools and holiday centers and (b) develop a school scheme for the consumption of fruit co-financed by EU, embedded in the CMO reform, with the goal of making fruit and vegetables available to children between the ages of 4 and 12 [23]. As an example, the School Fruit Scheme (SFS) is the most recent EU effort to align questions of health and nutrition with those of the agricultural policies. SFS foresees that “the concession, within the context of a fruit and vegetable distribution scheme in schools, of a community fund to provide fruit, vegetables and products derived from the banana to children in educational institutions, should lead young consumers to appreciate fruit and vegetables and increase their future consumption” [32]. Importantly, for the first time, the epidemic of obesity in European countries lead to the connection between the interests of agriculture and of the agro-food industry with questions of nutrition and its relationship to health. Currently, this program is still active and, in 2016, there was a merging of the SFS and the school milk scheme, now known as School Scheme, with a budget of 250 million euros per year [33].

At the EC level, so far, CAP, which has an enormous influence on what is produced and consumed, has paid little attention to the promotion of a healthy diet for European citizens in its objectives and orientations. However, a new revision of this policy is underway, in the context of the UK’s exit from the European Union and, for the first time, one of CAP’s general objectives will consider the need for this policy to be aligned with the promotion of a healthy diet. It is therefore expected and hoped for, that in the future, there will possibly be more nutrition-sensitive agriculture policies [34].

Finally, it is worth noting, that the importance given to nutrition and NCDs in the most recent United Nations SDGs, defined for 2030, may present an opportunity for the implementation of a more ambitious strategy in the field of nutrition within the EU. The EU made a commitment in achieving United Nations SDGs, and some actions to strengthen EU activity in this field are already visible. In the context of SDG 2, among other activities, the reinforcement of community programs which aim to promote access to food in socioeconomically vulnerable populations is highlighted as well. In 2014, the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived, which foresees the distribution of food/meals to more low-income populations was created, taking into consideration for the first time the need to guarantee that this must be compatible with a healthy diet [35].

Portugal’s progress in the context of diet and nutrition strategies from 2010 to 2020

The decade 2010-2020 became a key moment of affirmation in terms of public policies in the field of nutrition in Portugal. During this period, the capacity to implement different actions benefited from the existence of several international guidelines in this field and from the experience from other countries. This capacity was also supported by the ad hoc past experiences in food and nutrition policy in Portugal, since the implementation of democracy in 1974, particularly since the 90s. For these reasons, below we describe some of the most important precursors to the national food policy. We also speculate that some of the positive results of this strategy, in terms of the number of actions implemented, may be related to its longevity, due to the fact that the national food policy was able to affirm itself above the occasional political cycles. Portuguese food and nutrition policy will also be described in this section, as well as its main implemented measures and achieved results.

Obesity as a public health problem was the basis for the first portuguese food and nutrition strategy (platform against obesity)

Platform against Obesity appeared in 2007, with the mission of putting in place the objectives defined in the European Charter for Counteracting Obesity, to which Portugal subscribed during the WHO conference which occurred with all Member States of the European region in Istanbul, from the 15th to the 17th of November, 2006. It arose as an integral part of a strategy for the reduction and prevention of NCDs at the heart of the Directorate-General of Health (DGS), and is constituted as a Division of the DGS, integrated into its organizational structure. Platform against Obesity, contrary to previous obesity national programs, intended to heavily target prevention, encompassing a series of measures for primary, secondary and tertiary prevention, but focused mostly on primary prevention. This strategy was already aimed to be intersectoral, including representatives from the Ministries of Health, Education, Economy, Agriculture, the National Association of Municipalities and Civil Society Associations. Despite this ambition, during these first years of implementation, emphasis was given to the collaboration with the Ministry of Education [36].

In its first year of implementation, Platform against Obesity co-existed with the National Program to Counteract Obesity, created in 2005 by a Ministry of Health Dispatch of the 28th of January. This program, conceptually developed for a more centered approach to secondary and tertiary prevention, became extinct on the 5th of September 2008 [37]. Therefore, it was at that time that the need to act in an integrated and intersectoral manner in the fight against obesity, and the need for a greater investment in measures of primary prevention, gained political recognition for the first time in Portugal. Of note is the fact that, as children are one of the priority groups of the Platform against Obesity’s intervention, Portugal was one of the first countries to adhere during this time to a surveillance system to evaluate childhood obesity managed by WHO, entitled Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI), which today is one of the biggest systems of monitoring childhood obesity at a global level. Of the broad series of measures projected by the Platform against Obesity, the development of a communication plan, that would make the Portuguese population aware of the problem of obesity and, likewise, the importance of a healthy diet and physical activity, was probably the area in which a larger operational investment was observed.

In fact, it was during this period that, thus so far, took place the largest campaign in Portugal for the promotion of a healthy diet and physical activity centered on the fight against obesity, particularly childhood obesity. This campaign was disseminated through the radio, television and other media. This strong investment was essentially related to the financial support given by Galp Energy, within the company’s social responsibility initiatives. During the first 2 years of its existence and due to this private partnership, Platform against Obesity had, up to that time, probably benefited of the highest budget. This awareness and communication campaign, designated as “Positive Energy Movement,” prioritized children and encompassed several distinct initiatives, namely a Portuguese Roadshow in schools and beaches called “Positive Energy Brigades,” a TV Program called “Positive Life” and the construction of the Platform’s website, aimed at disseminating quality information in this field.

During this period, important legislative measures were also being taken at other levels. Measures which, in some cases, remain in place to this day. Namely, measures to regulate the nutritional profile of some food categories, particularly the Law No. 75/09 of 2009, which defined the maximum salt content in bread (<1.4 g of salt per 100 g of bread) [38], and measures to regulate the availability of food in specific public spaces, such as in educational facilities, namely the publication of theCircularsNo. 14/DGIDC/2007 and 15/DGIDC/2007 on Food Standards for School Meals [39,40], andCircularNo. 11/DGIDC/2007 on guidelines for food supply in school buffets and vending machines [41]. Consequently, there was a marked and large investment in the improvement of the food supply in school meals. Since 1984, the management of school meals from pre-school to primary school are a responsibility of Municipalities; however, with the publication of Dispatch No. 22 251/2005 of the 21st of October and Decree Law No. 55/2009 of the 2nd of March, questions related to nutritional quality and food hygiene at all levels of schooling, became the responsibility of the Ministry of Education, namely the Directorate-General of Innovation and Curriculum Development (DGIDC) [42,43]. It was in this context that the several guiding documents cited above were developed.

The beginning of the decade also marked the implementation of the School Fruit Scheme (SFS), as well as (EU) Regulation No. 13/2009 by the Regulation Council and (EU) Regulation No. 288/2009 by the Commission. The distribution of fruit in Portuguese schools, started with the primary schools, during the 2009/2010 school year. In fact, the guideline for the EC to implement a strategy for the distribution of fruit in schools was approved in 2007, during the Portuguese Presidency of the European Union Council, and was then implemented in 2009 [44]. Taking into consideration the involvement of agricultural, health and education sectors, it was possible to consider that the SFS strategy represented the first intersectoral strategy on food and nutrition in Portugal.

1 From the platform against obesity to the first broader food and nutrition strategy: the PNPAS

Despite the Platform against Obesity already presenting a set of characteristics which allows to think of it as the first concerted strategy on obesity, there was still an urgency for Portugal to implement a more comprehensive food and nutrition strategy. A strategy that would not be limited to valuing diet as, albeit, an important factor for the prevention of a given disease, but one which would aim and be capable of formally considering the importance of promoting a healthy diet as a key determinant for the promotion of health. Without downplaying obesity as one of the main current public health problems, the problems stemming from an inadequate diet are known to be more complex and wide-ranging.

The growing body of evidence that highlights inadequate diet as a main risk factor contributing to the Portuguese population loss of years of healthy life, as well as the high costs of NCDs to the national healthcare systems, contributed to an interest at a political level, in creating a new food and nutrition national program [7].

So, 2012 marks the creation and implementation of the PNPAS. PNPAS was approved through Dispatch No. 404/2012 of the 3rd of January 2012, having been considered one of the eight Priority National Health Programs to be developed by the Ministry of Health. In the context of the National Health Plan Revision and Extension until 2020 [45], PNPAS was renewed as one of the current 11 Priority National Health Programs, through the publication of Dispatch No. 6401/2016, of the 11th of May [46]. In accordance with this Dispatch, PNPAS now integrates the Platform for the Prevention and Control of Chronic Diseases alongside the Prevention and Control of Tobacco, the Promotion of Physical Activity and Prevention of Diabetes, Cerebral-Cardiovascular Diseases, Oncological Diseases and Respiratory Diseases.

PNPAS’s mission is to “improve the population-wide nutritional status, stimulate the physical and economic availability of healthy foods and create conditions so that these may be valued, appreciated, consumed and integrated into daily routines.” Since its creation, the general goal of this program has been to encourage a healthy diet and with this subsequently, to improve the nutritional status, to impact directly on the prevention and control of the most prevalent diseases at a national level (cerebral-cardiovascular, oncological, diabetes, obesity), to simultaneously allow for the economic growth and competitiveness of the country, such as to support agriculture, environment, tourism, employment and professional qualification. At that time, it was already recognized that one of the biggest challenges of a national nutrition policy would be to reconcile the international recommendations regarding evidence-based best practices for improving the health status of the populations with the established food systems and the need to promote economic growth and sustainability through job creation. It must be noted that PNPAS appears amidst a deep economic and social crisis, under foreign financial rescue intervention, and at a time when international health strategies did not seem sensitive or aligned with the hardships that most Southern European countries and Ireland were experiencing.

Even so, PNPAS was designed around 5 general objectives: (a) to increase knowledge about food consumption, its determinants and consequences, in the Portuguese population; (b) to modify the access to certain foods, namely within the school and the workplace environments, and in other public settings; (c) to inform and empower citizens regarding shopping, preparation and storage of healthy food, especially those most vulnerable or low-income; (d) to identify and promote intersectoral actions which encourage the consumption of good nutritional quality food in an articulate and integrated way with other sectors, namely agriculture, sports, the environment, education, social security and local authorities, and (e) to capacitate the qualifications and conduct of different professionals who, owing to their roles, may influence knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding food and nutrition [47].

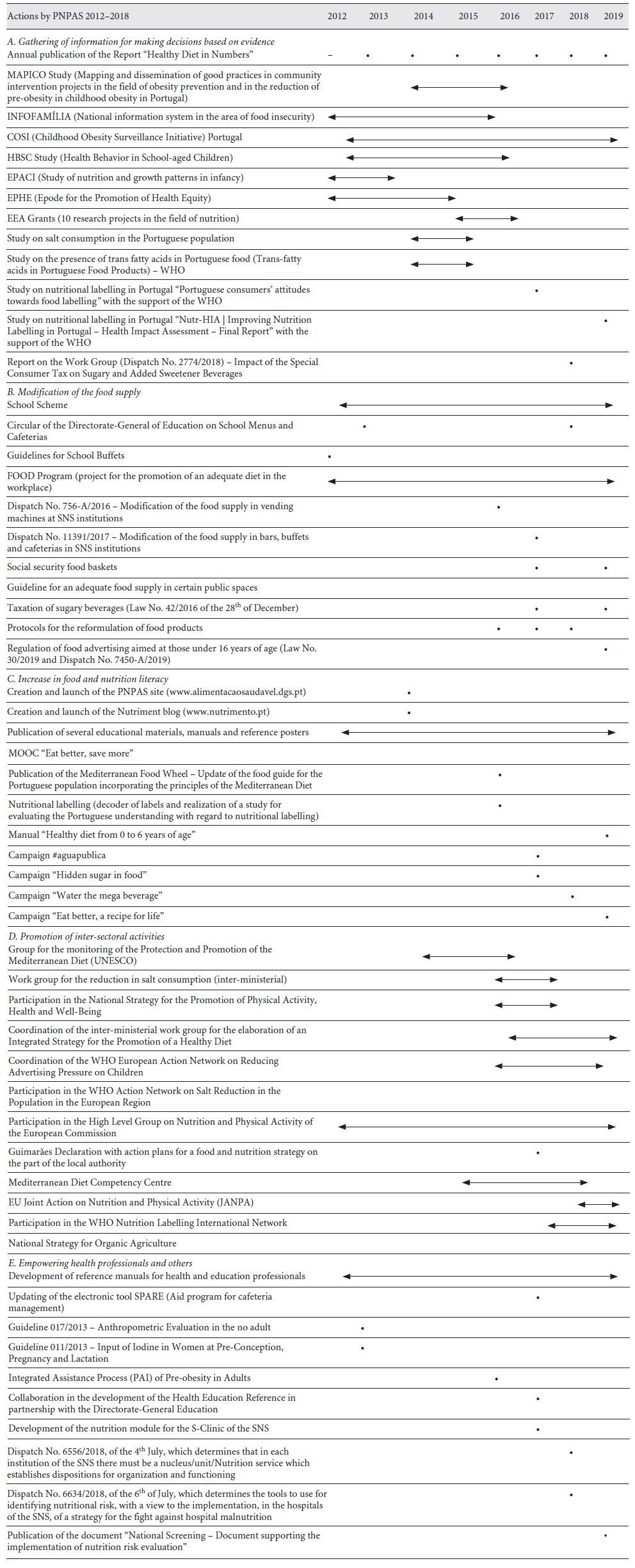

A. Gathering of information for evidence-based decision making

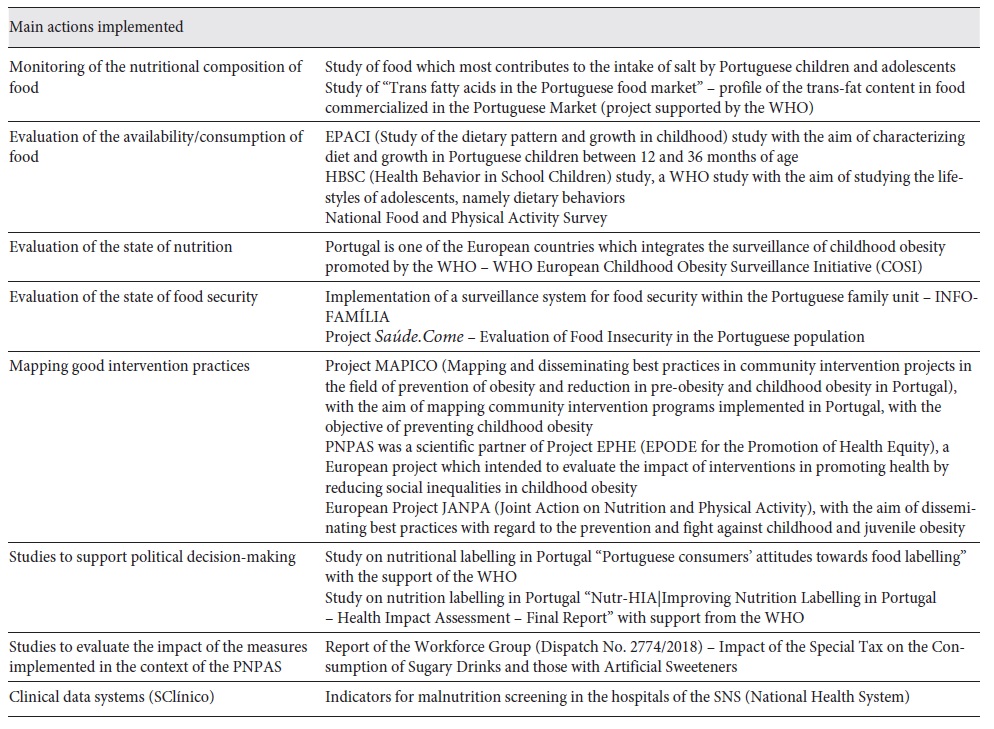

The regular gathering of quality information on the food and nutritional status of a population, is essential for developing a national food and nutrition policy. Whether at the level of planning and implementation, or at the level of monitoring of the defined strategies and the evaluation of its results/effectiveness. With this aim, PNPAS, throughout its existence, has been developing a set of actions with a view to gathering information at different levels: (a) information on the trends of the food supply available in the market; (b) trends in nutritional composition of foods available, namely, the salt, sugar and fat content; (c) trends of food availability/consumption; (d) nutritional status and also (e) the determinants and consequences of food consumption, for example, food insecurity. On the other hand, PNPAS has also sought to develop or promote the development of studies which aim to map best practices of intervention in the field of promoting healthy eating/obesity prevention. Table 1shows the main actions developed by PNPAS, in the context of its first objective. PNPAS has also supported (scientifically and/or with financial support) the development of several research projects in partnership with higher education institutions. In recent years, PNPAS has supported a financing program for research projects, for the health field, financed by the European Economic Area Financial Mechanism (EEA) Grants. Nutrition was one of the priorities, with approximately 10 projects having been financed (for a total of approximately 3 million euros), these with the aim of reducing social inequities in nutrition. Financed projects encompassed different areas, a highlight being the 2nd National Food Survey (IAN-AF). In Portugal, the first national food survey took place in 1980 and was the only national survey for more than 30 years, so this latest survey, performed in 2016-2017, provided extremely important information for defining strategies in this area. Besides the national food survey, PNPAS defined the following areas as priorities for research project support: (1) evaluation of the nutritional status of the elderly; (2) evaluation of food insecurity in Portugal and (3) evaluation of iodine levels in Portuguese children, as well as evaluating the impact of the strategy of using iodized salt in Portuguese public school meals. Projects in all these areas obtained financing, which greatly contributed, and will carry on contributing towards making informed policy decisions.

On the other hand, PNPAS has also sought to gather and compile all existing information regarding food consumption, and the nutritional and health status of the Portuguese population. As a result, PNPAS produces an annual report -“Alimentação em números”(“Diet in numbers”) - compiling the most relevant data, statistics and information regarding food and nutrition in Portugal, together with the monitoring and evaluation of the implemented strategies. Within this context, we give special importance to systems which enable the gathering of information on a regular basis. Digital healthcare information systems have the capacity to gather relevant data based on healthcare professionals records, namely the healthcare information system of the Portuguese National Health System (SClinico), which has been proven an important source of data, introduced daily by the health professionals in the context of their clinical practice. The data gathered in this context, allows for generating indicators regarding not only food consumption, but also, the nutritional status alongside nutrition care monitoring (e.g., indicators related to hospital malnutrition screening). These will become increasingly relevant in informing national food and nutrition policies (Table 1).

B. Modification of the food supply

The inability to put a stop to the rapid growth of NCDs has led to a reflection on the apparent failure of the more conventional strategies, that is, the ones centered on improving health literacy. In this sense, several researchers began to sound the alarm regarding the existence of environments which promote disease, and in the particular case of diet, of environments obesity promoters or the so called “obesogenic environments” [48]. These are perceived as those physical environments where it is easy and cheap to find, large quantities, of energy-dense but nutrient-poor foods, combined with very limited offerings of seasonal, fresh and nutrient-dense foods. In this regard, several documents from the WHO and other health organizations have been appealing for the implementation of multisectoral strategies [20,21,49,50], which progressively integrate proposals for the regulation of availability and access to food, particularly imposing regulations on unhealthy foods such as soft drinks or products with high levels of salt, fat and sugar.

This work has been fraught with difficulties as limiting access and changing food environments, in light of issues related to freedom of choice, requires proper justification. Furthermore, one of most challenging tasks in public health, will always be attempting to regulate different food operators and products, within a market which sees itself as free and without barriers.

Nevertheless, Portugal’s intervention in this area, despite being in its early stages, has been gaining a wider expression. Albeit, the worry of interfering in a still recovering economy, added to the legal impositions at the heart of the European Union, are more often than not obstacles to the regulation of the food supply. Despite these concerns, in recent years, Portugal has implemented a set of measures aimed to directly influence the availability of certain foods. A large part of these measures are an integral part of the National Health Plan 2012-2016 (extension until 2020), which defined, as one of its 4 strategic axis, the “Healthy Policies,” which argue that all sectors of the society should contribute to the creation of environments that may promote health and the well-being of its populations. Below, we highlight some of the more recent measures either directly or indirectly carried out by PNPAS.

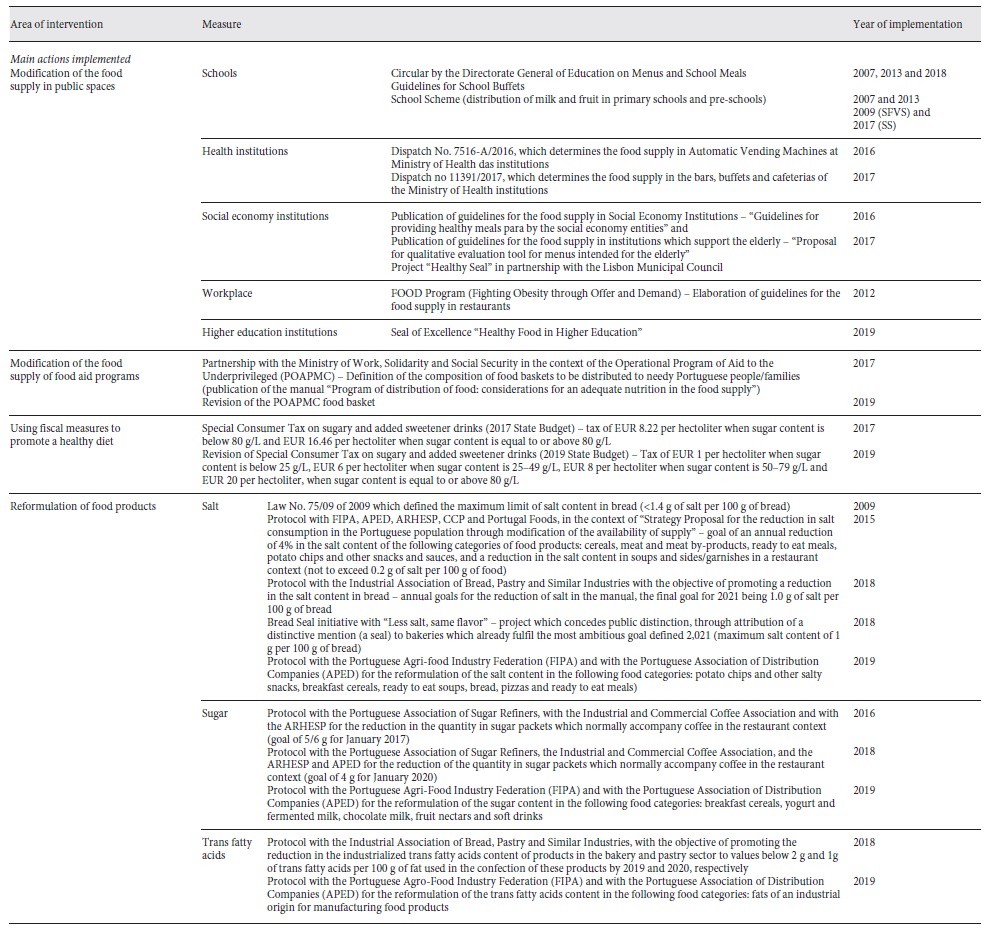

Modification of the Food Supply in Public Settings. One of the most urgent priorities continues to be the modification of the food supply and environment in schools. PNPAS, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, published new guidelines for school buffets/cafeterias (2012) and new guidelines for school meals (lunch; 2013 and 2018). These 2018 guidelines for school meals, encouraged for, among other initiatives, the expansion of these recommendations to all levels of education and the inclusion of guidance for vegetarian and Mediterranean menus.

During this period, several measures were also implemented for modifying the food supply in other public settings, namely healthcare, social service or charitable institutions, elderly residential or assisted-living facilities and workplaces.

Within the context of healthcare institutions, the Ministry of Health limited the availability of certain food products in vending machines and in the cafeterias/buffets serving the National Health System. Through Dispatch No. 7516-A/2016, published in the Portuguese official documentDiário da Repúblicaon the 6th of June, 2016, henceforth, would only be permitted in vending machines, food products that would fit within a PNPAS-defined adequate nutritional profile. Later, at the end of 2017, a further Dispatch No. 11391/2017, in which, this nutritional profiling was, then, to be extended to other healthcare non-clinical food provision, namely in buffets and cafeterias. By then, the Regional Health Administrations, in the North and in Algarve, had already rolled out this measure throughout their regions, but this Dispatch allowed for a national standard.

PNPAS also intends to stand for the quality of the food supply at social service and charitable institutions, supporting their essential role next to vulnerable population groups (e.g., low-income, children and the elderly). In this context, PNPAS elaborated several documents providing guidance, entitled “Guidelines for the supply of healthy meals by the social services and charitable entities” [51] and “Proposal for a qualitative evaluation tool for meals for the elderly” [52]. In addition to these documents, PNPAS has also collaborated on different community intervention projects, namely in partnership with the Lisbon Municipality, with the objective of optimizing their community meals service. There was also the attribution of a “Healthy Seal” to institutions fulfilling and catering for a given set of criteria related to the principles of the Mediterranean diet.

Lastly, the promotion of a healthy diet at the workplace is also considered of extreme importance. Since, 2012, the PNPAS has collaborated with FOOD Programme (Fighting Obesity Through Offer and Demand), a European program of the Edenred Group, which promotes the adoption of healthy lifestyles by workers through healthy food provision. In the context of this program, among many other initiatives, food guidelines directed at restaurants were developed, and a restaurant certification process was initiated for those that complied with “Restaurant FOOD.”

With the same thought, the higher-education student population was also identified as a risk group for unhealthy dietary habits and weight gain because their time at University may often represent a critical period impacting individual dietary habits. Hence, higher-education students should also be considered a priority, as this the moment in which young adults acquire more freedom and independence, and start taking responsibility for choosing, purchasing, and preparing food [53,54]. For this reason, it is felt that higher-education institutions should be taking on a central role, by promoting and facilitating a healthy diet. To further encourage higher- education institutions to fulfil this role, PNPAS developed a seal of excellence, entitled “Healthy Diet in Higher Education.” Validating their strides and efforts in this field.

Modification of the Food Supply of Food Aid Programs. One of the current main challenges for food and nutrition policies are social inequities in accessing an adequate diet. Associated with this challenge, the improvement of the food supply of the food aid programs for underprivileged people is one of the priority strategies. The high prevalence of food insecurity and the higher prevalence of overweight/obesity and other NCDs in more socioeconomically vulnerable groups of the population, suggest the need for an intervention directed at these at-risk groups. In this context, PNPAS has collaborated with the Operational Program for Aid to the Underprivileged (PO APMC), coordinated by the Social Security Ministry, which defines the composition of the food baskets for those Portuguese individuals/families in need. Now, this program reaches 60,000 families annually. The objective was to ensure the nutritional adequacy of the food baskets supplied. Guidelines for defining the composition of the food baskets were elaborated (“Food aid program: considerations for a nutritionally adequate food basket”) [55] plus, a document with supporting the appropriate use of the food provided (“Guidance for adequate use of the food basket of the Operational Programme for Aid to the Underprivileged [POAPMC], 2014-2020”) [56] and, lastly, a practical suggestion with a compilation of recipes inspired by the selected foods (“Protein providing foods in the POAPMC food basket: nutritional value”).

After evaluating the results of this food aid model, a year and a half after the beginning of the distribution of these food baskets, there was a review proposed in time for the second phase of distribution of PO APMC. This new proposal intended to bring closer the food distributed, as much as possible, with the beneficiaries’ consumer habits, and their dietary and food preferences, so that at the same time there was an increase in the variety of food and a reduction in food waste. All these changes were tailored, and made possible, without having significant implications or undermining the nutritional adequacy of the proposed food baskets [57].

Use of Fiscal Measures for Promoting Healthy Diet - Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. The excessive free sugar intake has been associated with dental caries [58] and overweight/obesity [59] and, consequently, the risk of developing NCDs [60]. From the evidence of high intake of sugar in Portugal, and its implications for public health, arose a need to implement strategies to tackle its insidious availability [61]. Taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages was one of the strategies implemented in Portugal, following the WHO guidance and other international experience. Since February 1, 2017, and through Law No. 42/2016 of the 28th of December 2017 State Budget, non-alcoholic drinks with added sugar or other sweeteners, are subject to a tax of EUR 8.22 per hectoliter when the sugar content is below 80 g/L and EUR 16.46 per hectoliter, when the sugar content is equal to or above 80 g/L. Drinks exempt from this tax are non-alcoholic drinks such: milk or “dairy alternative” beverages (e.g., soy, rice, oat, almond, hazelnut, coconut); fruit juices and nectars; and drinks for special dietary needs or nutritional supplements. With this measure, it was hoped that the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages would be discouraged, enabling a reduction in the overall consumption of sugar, which in Portugal reaches numbers far higher than the maximum recommended levels by the WHO, that is, a daily intake not exceeding 10% of the total energy intake.

According to preliminary data from an evaluation study on the impact of this tax, and based on data provided by the Portuguese Association of Non-Alcoholic Soft Drinks (PROBEB) and on data form from the Tax and Customs Authority, in 2017 it was possible to identify a drop of 4.3% in sales relative to this period, and a reduction of almost 50% in the consumption of drinks with a sugar content above 8 g/100 mL, which may be the result of either the drink reformulation process or an acquired preference for consuming lower sugar content ones. In accordance with data given by PROBEB, comparing 2016-2017, a reduction of 15% in the total volume of sugar consumed was observed, representing a total volume of 5.630 tons of sugar. Interestingly, the existence of this tax may have encouraged food product reformulation during this period. Though, it may have also induced an overall reduction in the consumption of these drinks, motivated not only by the increase in price, but also by some disfavor, by the increased consumer perception of the health risks attached to these beverages. The transference to the consumption of other types of drinks still taxed at a lower rate must also be considered [62].

Considering the results of this tax in terms of reformulation of the sugar content in soft drinks, Law No. 71/2018 of the 31st of December from the 2019 State Budget, contemplated a revision of this tax and the willingness to promote further sugar content reductions by installing new tax tiers for the beverages industry. This way, the Special Consumer Tax on Sugary Drinks and Added Sweeteners began contemplating, more recently, 4 levels of taxation: EUR 1/hL - drinks with a sugar content below 25 g/L; EUR 6/hL - drinks with a sugar content of between 25 and 49 g/L; EUR 8/hL - drinks with a sugar content between 50 and 79 g/L and EUR 20/hL - drinks with a sugar content equal to or above 80 g/L.

Plan for the Reformulation of Food Products. Following on, the dialogue and collaboration with the food industry are of utmost importance to achieve a better nutritional quality of foods, and this will usually come about by promoting food product reformulations.

In 2015, a group Dispatch from the Ministries of the Economy, Agriculture, the Ocean and Health (Dispatch No. 8282/2015 of the 29th of July), determined the creation of an inter-ministerial working group with the aim of proposing a set of measures for reducing the consumption of salt by the Portuguese population, particularly measures for the reduction of salt content in both, the food products and the food supplied in restaurants. This working group resulted in an agreement with the food manufacturers, distribution, retail and restaurants (FI PA - Federation of the Portuguese Agri-Food Industry, APED (Portuguese Association of Distribution Companies), ARHESP (Portuguese Association of Hotels, Restaurants and Similar Services), CCP (Confederation of Commerce and Services of Portugal), and Portugal Foods. It also resulted in the publication of the “Strategy Proposal for the reduction in the consumption of salt in the Portuguese population through modification of food supply” which defined targets for salt reduction in food products and salt content in soups and sides/garnishes in the food catering and restaurant sector [63].

DGS also signed a protocol with the Association of Sugar Refiners of Portugal, The Industrial and Commercial Coffee Association, ARHESP and APED for reducing the sugar quantity in the single-use packets which traditionally accompany the coffee cups in the hospitality businesses (maximum of 5/6 g for January 2017, and 4 g for January 2020).

Similarly, and in order to promote a reduction in salt content in one of the most important contributors of its intake in the Portuguese population, DGS established an agreement with the industrial associations of bread, pastry and similar industries. In this agreement, annual targets were defined for the progressive reduction of salt content in bread, with a final target, to be achieved by 2021, of 1.0 g of salt per 100 g of bread. Like other times before, also in this setting an encouragement campaign was initiated, so that Portuguese bakeries may achieve the defined final target for salt content more quickly. For that, the initiative Bread Seal “Less salt, same flavor” was launched. The intention of this initiative is to concede a public distinction, through attribution of a distinctive mention (a seal) to bakeries which already fulfil the most ambitious target defined for 2021 (maximum salt content of 1 g per 100 g of bread).

The agreement between DGS and the industrial associations of bread, pastry and similar industries also defined limits for trans fatty acid content in pastry products, given that this is one of the food categories where they are most prevalent. The aim of this agreement with bread-making and pastry sectors is to, going forth, promote a reduction in the trans fatty acids content for values below 2 g and 1 g per 100 g of total fat, by 2019 and 2020, respectively.

In 2019, DGS made a broad co-regulation agreement for reformulation of processed foods with the Federation of Portuguese Agri-food Industries (FIPA) and the Portuguese Association of Distribution Companies (APED). This broad co-regulation agreement sets voluntary targets for reducing sugar, salt and trans-fatty acids in a range of processed foods. For the reduction in the salt content, the following categories were considered: potato chips and other savory snacks (reduction of 12% by 2022), breakfast cereals (reduction of 10% by 2022 and 1 g of salt per 100 g of product for infant cereals), ready to eat soups (0.3 g per 100 g of product by 2023), bread (1 g per 100 g of bread by 2021), pizzas (reduction of 10% by 2022) and ready to eat meals (0.9 g per 100 g of product by 2023); for reducing sugar content, the following categories were considered: breakfast cereals (reduction of 10% by 2022), yogurt and fermented milk (reduction of 10% by 2022), chocolate milk (reduction of 10% by 2022), fruit nectars (reduction of 7% by 2023) and soft drinks (10% reduction by 2022). The reformulation of trans fatty acid content included fats and spreads for manufacturing food products (<2 g per 100 g of fat). In each of these food categories, the intention was to promote the reformulation and monitoring the products which represented at least 80% of volume of sales. Monitoring process of this co-regulation agreement for food reformulation is conducted by Nielsen, an independent entity, and is supervised by the Portuguese National Health Institute (INSA). The main metrics used to monitor progress were the sales-weighted averages for salt and sugar content in each category of food products by year, and total volume of sugar and salt sold per year.

All these actions to encourage food reformulation, surely, will be one of the most important measures for future health gains. However, voluntary initiatives through commitments with the food industry have only enabled small and slow changes. We are aware of these results from other countries’ experiences, namely England, and the Portuguese experience also seems to corroborate these results. A recent publication based on a modelling study suggested that if the more ambitious reformulation targets were met, the projected reductions in intake in 2015-2016 for salt would be from 7.6 to 7.1 g/day, in total energy from 1,911 to 1,897 kcal/day due to reduced sugar intake and in total fat (% total energy) from 30.4 to 30.3% due to reduced trans fat intake. It was also projected that these changes in salt, sugar, and trans-fat intakes would result in 248 fewer premature NCD-related deaths [64].

Using regulatory instruments, as in the special consumer tax on sugary beverages, as well as front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes, seem to be much more compelling in achieving reformulation of products. The broad agreement for the reformulation of food products, signed in Portugal in 2019, did not come close to the targets initially outlined by the DGS. Some Portuguese food manufactures showed a strong resistance to the reformulation of food products, namely the dairy and charcuterie sectors, and when the reformulation is a voluntary consideration, it is challenge to sustain ambitious goals.

A summary of the main actions implemented to change food environments is described in Table 2.

C. Improve population’s food and nutrition literacy

Nutrition education is the most traditional area of intervention within the strategies for promoting a healthy diet. As we have previously discussed, a food and nutrition policy should combine a set of actions to change food environments complemented by, another, set of actions to improve food and nutrition literacy. Thus, one of the main objectives of the PNPAS must still be the continued dissemination of information so that empowered citizens may choose to shop, handle and prepare healthy food. In recent years, the PNPAS invested in the development of an innovative digital strategy that permits the dissemination of information directly to the general population, also supporting and capacitating health professionals and others interested. Therefore, different formats were developed for improving food and nutrition literacy throughout the life cycle, so that these messages reach large audiences in a cost-effective way. Among the main strategies, a highlight is the launch of 3 digital platforms: 2 websites (“Intelligent Diet” and “Healthy Diet”) and a blog (www.nutrimento.pt), with the objective of reaching different publics, adapting the message/content/information. The digital channels and the use of social networks (Twitter and Instagram), were considered the preferred channels for disseminating information, making them the standard at the national level. The communication strategy also encompassed the production of podcasts, reference manuals (posters, guidelines), not only for health professionals and institutions, but also for the education sector and online training (Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) “Eat better, save more”).

Alongside this effort, during the period 2017/2018, 3 national public campaigns to promote healthy eating were launched: Juntos contra o sal (Together against salt), Juntos contra o açúcar (Together against sugar), Juntos pela Alimentação Saudável (Together for healthy eating), using public figures and a strong media and social network presence. DGS signed a collaboration protocol with the 4 main Portuguese television stations (RTP, SIC, TVI and Porto Canal) for creating national campaigns promoting public health. The first television campaign was entitled“O Açúcar Escondido nos Alimentos” (Sugar Hidden in Food). In 2018, another campaign was also launched to promote water consumption, in partnership with the Portuguese Association of Water, Natural Mineral and Springs Industries (APIAM). In 2019, the first campaign for promoting a healthy diet in Portugal, using a strategy of mass dissemination, with a national coverage across different media (television, radio, outdoors, public transport, social networks and regional press), was launched. This campaign, with the slogan“Comer melhor, uma receita para a vida” (Eat better, a recipe for life)was meant to challenge the Portuguese to, step by step, bring together the “ingredients” which were most lacking in their diet (fruit, vegetables, pulses and water), turning them into a “recipe” for a lifelong positive change.

To further embed food and nutrition literacy in the population, the highlight of Mediterranean Diet became one of the PNPAS’s flagships and several educational materials were developed. This was reinforced during the update of the Portuguese food guide based on the principles of the Mediterranean diet - “Guide for a Mediterranean Diet.”

Regulation of Food Advertising to Children. Childhood obesity is greatly influenced by the advertisement of food high in fat, salt and/or sugar (HFSS foods). The health impact of unhealthy food advertising is very pronounced in children and young people. Moreover, young people also play an important role in their parent’s food choices [65]. The need to ensure that children and young people have the opportunity to grow in an environment which encourages a healthy diet, and which promotes the maintenance of an adequate weight, led the WHO to invite Member States to introduce restrictions on food marketing to children, covering all media channels and including digital marketing. Since April 2019, Portugal introduced a law which applies restrictions to food advertising directed at those under 16 years of age (Law No. 30/ 2019, of the 23rd of April). This law foresees the banning of advertisement of high energy value and high sugar, saturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids and salt content food products, in instances such as: (a) For a 30-min period, before and after any television and on-demand audiovisual programs and radio services targeted at children or any program with an audience of at least 25% under the age of 16, including any form of advertising in their breaks; (b) in cinemas, in movies age-rated under 16 years of age; (c) in publications intended for young people under 16 years of age; (d) on the Internet, through webpages or social networks, as well as in mobile applications for devices using the Internet, where their content is intended for young people under 16 years of age [66].

This new law gave the DGS responsibility for defining the nutrient profile model for restricting food advertising to children. Nutrient profile model was developed by PNPAS and published in August 2019 through Dispatch No. 7450-A/2019. Nutrient profile model for the purposes of applying Law No. 30/2019, was based on the WHO nutrient profile model - WHO Regional Office for Europe Nutrient Profile Model - to which changes were introduced, with the objective of aligning the limits for some nutrients in some of the food categories, with the values defined by legislation from the European Union. Other changes reflect the targets of the agreements made by Portugal in the context of food reformulation, as well as an analysis of the nutritional composition of foods available on the Portuguese market and the limits imposed by the redaction of Law No. 30/2019 of the 23rd of April.

Approval of this Portuguese law regarding the restrictions to food advertising to children was an important step towards the modification of the obesogenic environment we live in. It places Portugal on the vanguard, given that few countries at an international level have been able to regulate this area, especially for digital marketing. However, this law, which took almost 3 years to approve, is not perfect. It was not possible to approve the restriction on food advertising to children under 18 years of age in Parliament. Law No. 30/2019 of the 23rd of April only focuses on advertising, leaving out other marketing strategies. It still presents some grey areas for advertising in the digital context, which currently is assumed to be the most powerful advertising channel. Finally, the redaction of the law which was approved by Parliament imposed some limits to the nutrient profile model developed by the DGS, namely the no possibility of considering some categories of food in which food advertising to children is not permitted in its entirety, and the no possibility of considering the total content of lipids and added sweeteners with items to take into consideration for the nutrient profile model. The DGS, through the PNPAS, also leads the “European Action Network on Reducing Advertising Pressure on Children,” a WHO network constituted by 28 countries of the European Region, and has as its objective, to find solutions for the reduction of pressure by marketing aimed at children, namely with regard to advertising for unhealthy foods.

Nutrition Labelling. The current model for nutrition labelling (nutrition declaration) does not seem to be capable of fulfilling its role of contributing healthier food options. Nutritional information, when presented only in a descriptive and quantitative manner (nutrition declaration in the form of a table which gives information such as energy value, lipid content, saturated fatty acids, carbohydrates, sugars, proteins and salt per 100 g/100 mL of food or its given portion), seems to be difficult to interpret for most consumers. It is in this context that several countries, at an international level, have been proposing alternative models of nutrition labelling, called front-of-pack nutrition label (FOP-NL). At the heart of the European Union, there is no consensus with regard to using a single model. However, some countries at the European level have been making an effort in this direction, namely the UK which proposes using a system of colors, using at its base traffic light colors (traffic light nutrition labelling) and, more recently, France which also implemented a somewhat more complex color system (Nutriscore system - 5-Color Nutrition Label). Portuguese government has not endorsed a specific simplified nutritional label model (FOP-NL). PNPAS has sought to produce scientific evidence that would enable a political decision at this level. One study recently performed on the Portuguese population, with the support of PNPAS and WHO, suggests that 40% of the Portuguese population did not understand the nutritional information currently presented on the nutrition declaration, and that this number increased when educational level decreased [7]. In 2019, PNPAS supported the undertaking of an exercise, the Health Impact Assessment (HIA) on nutrition labelling, with technical support from the WHO. Results of this study [67] show that the probability of the participants choosing a healthier food was 3-5 times higher when a FOP-NL is used, compared to the currently existing situation (nutrition declaration). This same study also shows that, despite traffic light nutrition labelling seeming to be the model which best allows Portuguese consumers to make healthy food choices, the results obtained for the remaining FOP-NL models suggest that they all present a potential for contributing to healthier food choices [67].

D. Promotion of intersectoral actions

PNPAS action plan is based on an intersectoral intervention approach, as the main determinants of food consumption are out of the health sector’s reach. This approach was concretized in Portugal in 2017, with the publication of the EIPAS, which includes 6 other ministries besides health, and which is explored more in-depth below [68].

E. Training of health and other professionals

The development of strategies that improve the training and qualifications of different professionals who, given their roles, may influence food knowledge, attitudes and behaviors, has been one of the important areas of action for PNPAS.

In Portugal, dietary counselling is an area shared by different health professionals; many of them have gaps in nutrition knowledge needed for nutrition care, hence the effort the PNPAS has been making in capacitating for a higher quality intervention. At the level of health professionals, the creation and implementation of the Integrated Assistance Procedure for Pre-obesity (PAI Pre-obesity) is highlighted, an integrated methodology for screening and early intervention used by professionals from the National Health Service (SNS), with the objective of reducing and/or controlling those overweight, and preventing the comorbidities of obesity. Also in this field, the PNPAS collaborated on the development of the integrated nutrition module of the national clinic registry platform (S-Clinico) of the SNS. This digital tool enables the systematic registration of clinical data by nutritionists, facilitating information-share between SNS professionals and contributing to the optimization of the care given.

The PNPAS has also developed a series of training activities online, for example, MOOC’S, a training model which ensures the training of a higher number of people at a lower cost. In the field of education, the PNPAS actively collaborated with the Directorate-General of Education (DGE) on developing the Health Education Reference. A guideline and reference document, aimed at pre-school, basic and secondary education, with the aim of promoting health literacy, the adoption of healthy lifestyles and the development of social and emotional competencies.

The PNPAS has developed several reference manuals in diverse areas, aimed at professionals and the general public, compiling the most recent scientific evidence, and elaborating norms and technical guidance destined for the National Health System and all its professionals.

The fight against hospital malnutrition has been one of the PNPAS’s areas of intervention. In the context of the working group constituted through Dispatch No. 5479/2017, coordinated by the PNPAS, with the objective of guaranteeing the supply of a nutritionally adequate diet, contributing to the quality of health care provided by the hospital entities of the SNS, Dispatch No. 6634/2018 was elaborated, which determines the identification of nutritional risk in all hospitalized patients of the SNS during the first 24 h after patient admission, and an evaluation every 7 days. Given the pressures associated with population ageing alongside financial hardship many times associated with it, this is surely one of the most pressing challenges facing the food and nutrition care process in Portugal in the coming years.

The main actions implemented in the context of PNPAS during the period 2012-2019 are described in Table 3.

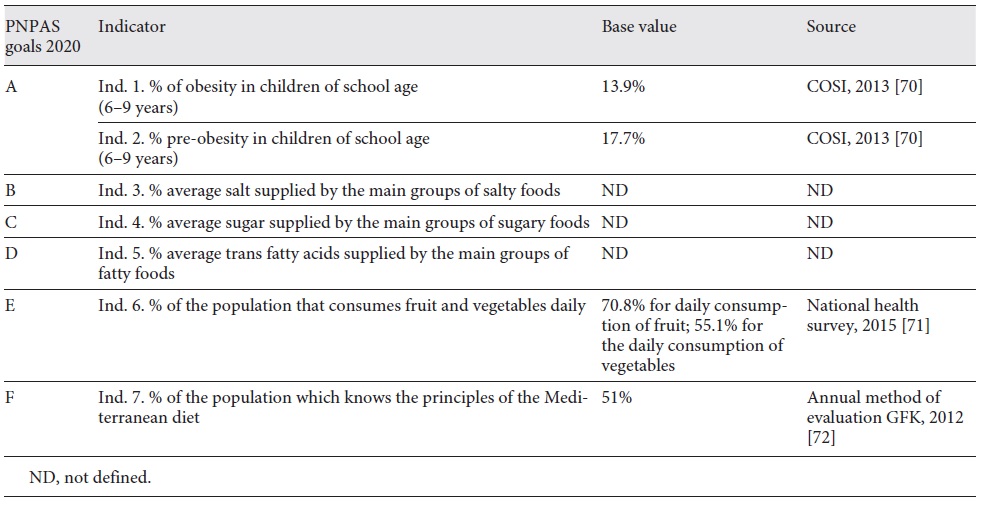

Indicators and health goals for 2020 in the context of the PNPAS

The program guidelines of the PNPAS, is one of the 11 National Priority Health Programs in the context of the National Health Plan Revision and Extension to 2020, and as such, a temporal outlook until 2020. For this purpose, the PNPAS defined 6 goals for 2020: (a) control the prevalence of pre-obesity and obesity in children and school-age population, to a null increase by 2020; (b) reduce by 10% the average in the amount of salt present in the main food suppliers of salt to the Portuguese population by 2020; (c) reduce by 10% the average amount of sugar present in the main food suppliers of sugar to the Portuguese population by 2020; (d) reduce the amount of trans fatty acids to <2% in total fat provided by 2020; (e) increase the number of people who consume fruit and vegetables daily by 5% until 2020 and (f) increase the number of people who know the principles of the Mediterranean diet by 20% until 2020 (Table 4) [69].

2. The increasing burden of NCDs in Portugal, and the need for an intersectoral approach in the field of food and nutrition: building the first inter-ministerial strategy for promoting healthy eating (EIPAS)

Since December 29, 2017, Portugal has offered an EIPAS structured on 4 main axes: (1) to create healthier food environments by modifying the types of food provided or sold in different public settings and promoting the reformulation of certain categories of food that are high in salt, sugar and fat; (2) to improve the quality and accessibility of healthy food choices for consumers in order to inform and empower citizens to make such choices; (3) to promote and develop consumer literacy towards healthy food choices and (4) to promote innovation and entrepreneurship focused on the area of promotion of healthy eating. EIPAS, published through Dispatch No. 11418/2017, presents a series of 51 measures which were adopted by the Ministries of Finance, Internal Administration, Education, Health, Economy, Agriculture, Forests, Rural Development and Sea [68]. The coordination of these strategies is the responsibility of the PNPAS.

This strategy presents 2 main, innovative challenges in the face of prior intervention models in Portugal. On the one hand, a proposal based on the approach “health in all policies” with the formal commitment by several governmental sectors (agriculture, economy, finance, education, municipalities, sea). On the other hand, an intervention centered on the modification of the food supply on the part of production and in public spaces, contrary to previous ones focused only on educating the citizen. This strategy interconnects with the PNPAS and expands it more effectively to other areas of inter-ministerial intervention and collaboration.

The main strategic documents on food and nutrition at international and EU level, as well as the main Portuguese strategic documents are described in Figure 1.

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to critically analyze the Portuguese food and nutrition policy followed during the decade of 2010-2020 and present its results, as well as understand the way in which these strategies are responding to the guidelines and intervention priorities established at an international level, namely the EC and the WHO. For Portugal, January 2012 is considered the defining moment of the decade, when a national, concerted policy strategy, with a specific, explicit mandate for improving the nutritional status of the nation was formulated. However, when arriving at this point, the long journey to it must be considered; indeed, in the 70 and 80s, Portugal produced, through Prof. Gonçalves Ferreira, a distinguished figure of the Portuguese nutrition, several proposals for creating a high-quality food and nutrition policy, coinciding with the Rome conference of the FAO/WHO. Unfortunately, in the aftermath of the 1974 revolution, following Portugal’s membership to the EEC in 1986, and later with the food crisis of the 90s, it became an oversight.

In November 2006, the Istanbul Conference took place. There, the ministers from the WHO European Region, in collaboration with the EC, finally place obesity at the top of their policy and public health agendas. For many reasons, the Istanbul Conference marks a turning point by leading to the introduction of changes to the model in the fight against NCDs, suggesting a concerted intervention by sectors, such as education, transport, agriculture and health, and at different levels, from the local to the national. For this purpose, the Member States (including Portugal) unanimously adopted the European Charter for Counteracting Obesity, which enabled policy guidelines for strengthening action in the Region [16]. The existence of a conducive European political environment is an important trigger for the implementation of public policies, as it is in the case of the food and nutrition policy in Portugal.

Beside the political factor, there is another associated technical and scientific factor. After the Istanbul Conference, the Division of the “Platform against Obesity” started working on the organigram of the DGS between 2007 and 2011. It introduces a model of intervention against obesity based on interdisciplinarity and prevention, which contrasts with the excessively curative and biomedical model in existence until then. During this period, the 2 people responsible for this division in the DGS were nutritionists, an emerging profession in Portugal, and the mediatic interest of this model awakened society’s interest and the political power for new forms of intervention in this area. From a technical point of view, we can say that these years are of great importance for affirming new forms of intervention with the participation of society as a whole, and for testing new models of communication with the target audience. Its results, particularly the population’s adherence to information on food and nutrition through the website, which becomes one of the most visited in this area in Portugal, and also the visibility which the problem of childhood obesity gathers, alert national politics to the need of going further in this domain.

The creation of the PNPAS, in 2012, occurs during the full-on economic and financial crisis in Portugal, and marks the beginning of a national food policy which will remain active during the entire decade. Within the scientific, technical and political domains, there are some factors which can explain the good implementation level of this strategy: the fact that it was being designed, implemented and led by the DGS, which is a central service with technical independence and administrative autonomy, relatively independent from political cycles; the fact that several responsible parties in the PNPAS maintained their political independence and lack of conflicts of interest with the food production and distribution sectors; the existence of a medium to long-term strategy, designed to go beyond the political 4-year cycles (between 2010 and 2020, 5 different political cycles have occurred, and there were no substantial changes to the political guidance in this area). These are some of the putative reasons that might explain the level of societal implementation and longevity of the PNPAS.

All of the current food policies are designed as models of intervention in society with implications for the appearance of NCDs which only manifest themselves later in life and, therefore, need to be prevented some decades earlier. Insightful to the need for an immediate political visibility, and the expected results in the medium term, the PNPAS has been working in several areas which enable just that and at the same time, supply responses to more immediate health problems. Examples of these approaches may be found in several interventions, such as: social and charitable sector activities; the fight against food insecurity in vulnerable or low-income groups; and the development of prevention models for hospital malnutrition at the time of patient admission and the support for improving nutrition knowledge in certain professional groups, for example firefighters. The fact that the PNPAS was launched during the economic and financial crisis in Portugal, under the supervision of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), has made this policy much more sensitive to questions of equity in health and in proximity with the real-world issues.

PNPAS’s long existence may also be explained by the multiple reference documents (manuals, guidelines, books…) produced, and by its decision-making which are of a highly technical nature and always based on the best scientific evidence and generally aligned with European and WHO policies in this area. Looking back, it has been of great importance to have a close relationship not only, with academia and universities, but also, with the WHO and with the EC, by engaging in the High Level Group on Nutrition and Physical Activity of the DG Santé.

A national policy with nutritional objectives, needs to be anchored in a broader food and nutrition strategy, with attractive, aspirational consumer food patterns, which can connect to society, its food history and the entire food chain. For this reason, the national food policy incorporated, from its beginning, the promotion and safeguarding of the Mediterranean Diet as a reference point. The possibility of Portugal sharing this reference as its cultural background, considered by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage of humanity, is an added value worth highlighting.

Another important factor was the fact that it created a very intuitive and broad channel of communication with the public. The PNPAS has possessed, since its inception, innovative models of communication (considering what was previously done in this area), such as a site and a blog recognized at the national and international levels, and the resource of social networks, in addition to new technologies such as podcasts, Instagram and Youtube, for communicating regularly with its audiences.

This innovative and comprehensive framework combined with the strategic gains achieved so far have not spared this policy from various challenges. The national food policy, as with the majority of public European policies in this area, recently re-centered its gaze towards the important role of intervention directed at the modification of food environments. The availability of scientific evidence implicating the influence of food environments on food consumption has been growing throughout the decade, here, under analysis [51,52]. To meet this challenge of modifying food environments, several concrete measures have been recommended by the WHO and by the EC, with a focus on: the use of fiscal measures; the regulation of food advertising and advertising aimed at children; the regulation of the food supply and provision in certain public spaces; the improvement of nutrition labelling models; and incentivizing the reformulation of food products. Currently, Portugal is introducing specific measures in all these contemplated topics. These broad intervention strategies contrast greatly with the tradition of past, encompassing nutrition and the nutritionist role within public health focused mainly on a model of identifying public health problems and tacking them solely through health education. This food policy transformation imposes on areas outside the traditional health professional remit and, by going beyond it, challenges established economic interests. While stating this, there is a need for greater support and political will so that even more action may be taken regarding food and nutrition. This ambition also requires unequivocal popular support. That will demand, a better explanation of what we do and why we do it. During this and subsequent decades, those responsible for the public food policies will increasingly need to become active political agents. And to maintain their capacity for intervention in society, they must have very well-developed traits of integrity and resilience, while acting in an area where there is practically no professional training. It is reasonable to anticipate this as one of the great challenges of the future.

In Portugal, recognizing the need for food policies to be interconnected with other policies in order to modify the food environment led to the creation, in 2017, of a formal structure, spearheaded by health and composed of 6 more ministries - EIPAS. From this experience, we highlighted the challenge in identifying common interests and incorporating the areas of social security and the environment in the future. Environmental questions associated with the increase in health inequities will be yet another main challenge in the food and nutrition policy of the future. The political commitment made by both the EU and by several Member States for “Sustainable Development Objectives” established by the United Nations, may become determinant by supporting the fight against inequity and a healthy diet alongside the environmental issues. While concurring in applying a whole-of-government approach [73, 74, 75], it is important to state that, in the first few years of EIPAS, there were many difficulties in identifying, or bringing to focus, common interests between all involved sectors. This has also been documented and felt elsewhere. Specifically, in the case of Australia’s National Food Plan, the “whole of government” had an opposite result in terms of public health nutrition, because agri-food industry interests dominated the policy agenda [76].