Introduction

On June 8, 2021 the World Health Organization reported more than 173 million confirmed cases of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide, including more than 3.7 million deaths 1. These numbers reflect the devasting pressure on and challenges in the health care systems around the world.

International databases are being updated daily to measure the incidence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as well as to track the number of cases diagnosed with COVID-19 over time. These databases include the: (1) WHO Coronavirus Disease Dashboard 1, (2) US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2, (3) EU Open Data Portal of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control 3, or even national dashboards such as: (4) the Official COVID-19 Dashboard for Austria 4 or the COVID-19 Dashboard maintained by the Robert Koch Institute in Germany 5. However, all of these databases are population-based databases and do not place a focus on high-risk groups such as health care workers. Concerning COVID-19, health care workers are recognised as a specific high-risk group 6.

Nurses and midwives make up the largest group (i.e., about 50%) of all health care workers, and especially nurses have been recognised as key players in crisis and post-crisis situations 7, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

In recent months, hundreds of papers have been published internationally on the topic of COVID-19. Many of the studies describe vaccine development efforts, specific treatment interventions 8),(9, or the pathophysiology of the underlying virus 10),(11.

Some of the papers place a focus on epidemiology 12 or lessons learned during COVID-19 13), (14. Others have been carried out to investigate how COVID-19 has affected patients 15), (16, nursing home residents 17, or older persons in the community 18.

We conducted a systematic literature search and found only a few studies that specifically addressed nursing staff and COVID-19 19), (20), (21. Some of these papers described the consequences of COVID-19 affecting nursing staff 22), (21. One study was carried out on nurses as COVID-19 patients 23, another focussed on a symptom cluster of ICU nurses who treated COVID-19-positive pneumonia patients 24, and one study considered SARS-CoV-2 infection rates among respiratory staff nurses 19. In another recent study, researchers investigated the experiences of nurses who worked in the Australian primary health care sector during the COVID-19 pandemic 25.

However, none of the above-mentioned publications provided detailed insights into the nursing staff’s COVID-19 symptoms, testing procedures/results, or diagnoses. In addition, based on the results of the literature review, no study has been thus far carried out to investigate the effects of settings and regional differences on reported symptoms and testing. However, such a study could provide researchers with important, comprehensive insights into COVID-19 infection rates in nursing staff. Furthermore, these study findings could indicate the settings and regions in which testing should start earlier if another pandemic occurs.

Materials and Methods

Aim

The current study aimed to investigate settings and specific regional differences concerning COVID-19 symptoms, testing, and diagnoses among nursing staff.

Design, Settings, and Sample

This study was conducted as a cross-sectional study, using an online questionnaire. To reach our target sample, we applied the snowball sampling strategy and used social media. We developed a questionnaire that was subsequently distributed to nursing staff throughout Austria, independent of their qualifications (e.g., nurse, nurse aid) and work settings (e.g., hospital, nursing homes). The main target group included nurses who were working at the bedside during the COVID-19 pandemic in Austria.

Data Collection Instrument and Analysis

We collected data from May 12 to July 13, 2020. For this study, we collected the following data: (1) demographics (e.g., age, gender) (2) region, (3) setting, (4) professional qualification (e.g., nurse, nurse aid), (5) job experience in years, (6) symptoms of COVID-19 experienced (Yes/No), and (7) whether the participants had been tested positive for COVID-19 (Yes, I was tested positive for COVID-19/No, I was tested negative for COVID-19/ No, I have not been tested for COVID-19 at all).

The main variables in this study were the region, setting, and whether the nurses had been tested, including the results. All of these variables were categorical variables for which we calculated descriptive statistics in percentages. We also conducted a bivariate analysis using the χ2 test and Cramér’s V as the effect size. A p value <0.05 indicates a statistically significant result in this study. This article follows the STROBE statement 26.

Ethics

On the first page of the online questionnaire, we provide the participants with information about the aim of the study, contact persons, as well as data security. All participants then had to sign a written informed consent form, in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union, to participate and continue the questionnaire. All data were collected anonymously. Ethical approval was granted by the responsible ethical committee.

Results

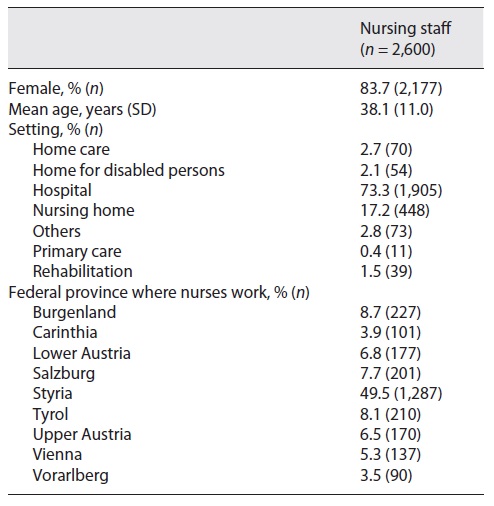

In total, 3,497 nursing staff members participated in the study, resulting in a large sample of questionnaires filled out online. Of this number, 892 questionnaires (25.5%) were incomplete: 56 of the invited persons chose not to participate; 567 participated, but did not complete the questionnaire, and 269 only read the welcome page of the questionnaire. In addition, we had to exclude data from 5 participants as they were 65 years or older, which is the retirement age in Austria. As a result, we were able to include data from 2,600 individuals in this analysis. Table 1 depicts the sample characteristics.

More than 80% (n = 2,177) of the nurses were women, and nearly half of the nurses worked in the province of Styria (49.5%, n = 1,287), Burgenland (8.7%, n = 227), or Tyrol (8.1%, n = 210). Nearly three-quarters of the nurses worked in a hospital setting (73.3%, n = 1,905). Table 2 describes the setting and regional differences concerning COVID-19 symptoms and testing reported by the nursing staff.

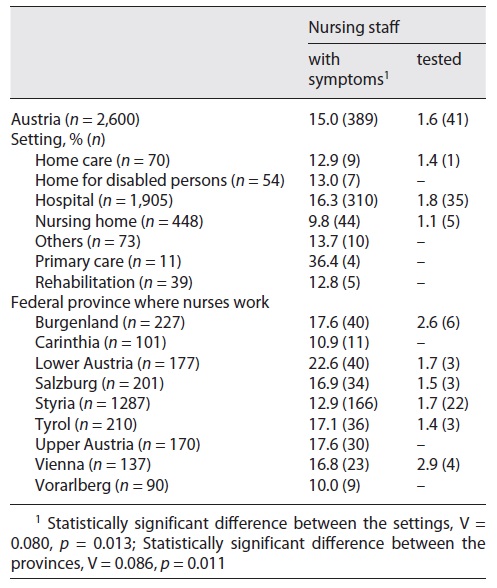

Table 2 Settings and regional differences with regard to symptoms of and testing for COVID-19 reported by nursing staff

Nearly every sixth nurse (15%, n = 389) reported experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. Of these nursing staff members, 16.3% (n = 310) of the staff in hospitals and 9.8% (n = 44) of the staff in nursing homes experienced COVID-19 symptoms. More than one-third (n = 4) of the nurses who worked in the primary care sector reported experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. We found a statistically significant difference for the regional setting and COVID-19 symptoms.

The highest proportion of nurses who reported symptoms worked in lower Austria (22.6%, n = 40), followed by Upper Austria and Burgenland (17.6%, n = 30; n = 40). In contrast, 10% (n = 9) of the nurses who worked in Vorarlberg reported that they experienced COVID-19 symptoms.

Our findings show that 1.6% (n = 41) of the participating nurses were tested for COVID-19. We could not identify any statistically significant difference between the settings (V = 0.041, p = 0.575) as well as the federal provinces (V = 0.060, p = 0.309) with regard to COVID-19 testing. The federal provinces where the most tests for nursing staff were conducted were Vienna (nearly 3%, n = 4) followed by Burgenland (2,6%, n = 6). All of the tested nurses (n = 41), independent of the federal province or setting in which they worked, were diagnosed with COVID-19.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effect of settings and regional differences on the reporting of COVID-19 symptoms, testing, and diagnosis by nursing staff. In general, nearly every sixth participating nurse (n = 2,600) reported experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. We found statistically significant differences between the settings and the federal provinces concerning the COVID-19 symptoms experienced. The highest proportion of nurses who experienced symptoms worked in lower Austria, followed by Upper Austria and Carinthia. Nearly 10% of nursing home staff and about 16% of staff working in the hospitals reported experiencing COVID-19 symptoms.

We identified one study in which the researchers focused on symptoms in COVID-19-positive health care workers 19. The authors described that most of the COVID-19-positive staff experienced at least one systemic symptom (i.e., any combination of the following: fever, headache, myalgia, or fatigue; n = 37, 78.7%) and at least one respiratory symptom (i.e., any combination of the following: cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, or chest tightness/pain; n = 41, 87.2%). In the health care workers who received a negative PCR test result, 59.4% (n = 95) reported at least one systemic symptom, and 71.9% (n = 115) reported at least one respiratory symptom. The differences between this study’s results and our results could be explained by the fact that we included not only nursing staff who had been tested. In Austria, the Ministry for Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection issued instructions for health care workers, specifically instructing them to perform personal observations and self-assessment of their symptoms. If they experienced a cough or fever, they were requested to call an established “health advice hotline” number (1450) to receive more information. The person contacted via this number would then decide whether someone would be tested or not.

Some of our results were surprising; we did not expect the highest proportion of nurses who experienced symptoms to have worked in lower Austria, followed by Upper Austria and Carinthia. These results were surprising because the first regions to report a high prevalence of COVID-19 were Tyrol (Ischgl, Kappl, See, Galtür, and St. Anton am Arlberg) and Salzburg (Pongau) 27. However, these findings might be explained by the fact that we asked the nursing staff retrospectively; at the time of our data collection, the provinces of Lower and Upper Austria were reporting relatively high numbers of COVID-19-affected individuals.

Although we could not identify any statistically significant difference between the federal provinces or settings concerning COVID-19 testing, we believe that it is of great importance to point out that the federal provinces with the highest numbers of tests were Vienna followed by Burgenland. In general, from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Austria up until 3 August, 910,437 individuals were tested. Of this number, 25% were from Vienna, 17.7% were from Tyrol, and 17.4% were from Lower Austria 4. These data contrast with our results. This might be explained by the fact that we only asked nurses if they had been tested, and the data for the above-mentioned tests include all tests conducted in Austria during this period. However, we find this contrast surprising, as the federal province of Burgenland had very low rates of COVID-19-affected persons as compared to the other federal provinces, such as Tyrol. One explanation for these findings might be the short distance between Vienna and Burgenland, i.e., the testing teams from Vienna might also have conducted tests in Burgenland.

In total, all of the tested nurses (n = 41), regardless of their settings or the federal province, were diagnosed with COVID-19. In the study by Bird et al. 19, 63 nurses participated in the study and 34.9% of these tested positive. Two other studies reported a similar percentage of COVID-19-positive health care workers. In these studies, 17% 28 and 29.1% 29 of the nurses tested positive for COVID-19. The difference between the results reported in these studies and our results might be explained by the relatively small number of nurses tested in general.

However, in our study we showed that all the nurses tested were diagnosed with COVID-19. This had two major consequences. First, if more nurses had been tested, we could assume that Austria would have a higher COVID-19 incidence. Second, considering that many persons are asymptomatic, and nurses who do not experience symptoms are not tested, these nurses might become “super spreaders.” This aspect should be carefully considered now when normal life is starting again.

Limitations

Every study has strengths and limitations. The first limitation of our study is that our sample is not representative of the Austrian health care setting. As an example, according to data collected in 2017 30, 53% per cent of all nurses were employed in hospitals, 33% in nursing homes, and 14% in home-care settings. In our study, nearly three-quarters of the nurses who participated worked in a hospital setting, only 17% worked in nursing homes and 2.7% worked in the home-care setting. Moreover, we also have to mention here that factors such as age differed between the regions and settings. However, it was not possible to conduct an age-adjusted analysis due to the small number of nursing staff that experienced symptoms (n = 389) and were tested (n = 41). Another limitation of this study might be that we asked the nurses retrospectively regarding their experiences with COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic began in Austria at the beginning of March, with a lockdown order issued on March 16, 2020. When we started the survey (May 12), shopping centres, shops, restaurants, cafes, bars, and nursing homes had already opened again. This retrospective view might have introduced a bias. However, most of the participants completed the questionnaire within the first 2 weeks after the online platform was opened.

Conclusions

It is of great importance that care workers should be given the possibility to be tested more frequently for COVID-19, even if they do not experience any symptoms, as nurses are taking care of the most vulnerable and high-risk group of patients. This aspect is of particular importance, as nurses are likely to spend more time with the patients/residents than any other health care professional and have been recognised as key players in the COVID-19 crisis. A first insight into the COVID-19 symptoms and the testing of nursing staff can help to increase the efficiency of public health actions in future pandemics. During further outbreaks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, we recommend shifting the focus from the critical and acute settings to, for example, nursing homes, where the most vulnerable and high-risk groups live. Ensuring the safety and health of nursing home residents, as well as high nursing care quality can decrease hospital admissions, health care costs, and consequently reduce morbidity and mortality in such pandemics.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted ethically following the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All participants then had to sign a written informed consent form, in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union, to participate and continue the questionnaire. All data were collected anonymously. This study was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the Medical University of Graz, approval No. 32-386 ex 19/20.

Funding Sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

All authors (M.H., D.E., and S.B.) are qualified for authorship by meeting all four of the following criteria: (1) have made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) given final approval of the version to be published; each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; and (4) agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.