Introduction

The ageing of the population is a relevant issue for societies, demanding better strategies to guarantee the quality of life. Loneliness among older people is widespread 1, requiring prevention and intervention measures 2. Loneliness has been widely studied, yielding several definitions. Overall, there are three points of agreement in the conceptualization. First, loneliness corresponds to the perception of a discrepancy between a person’s desired and actual networks of relationships; thus, it is not having few social contacts but perceiving that the relationships are not satisfying. Second, loneliness is a subjective experience; therefore, people can be alone without being lonely or might be lonely in a crowd. Third, loneliness is an unpleasant and distressing experience 3,4.

Loneliness in older adults has been a major public health issue since before the COVID-19 pandemic, due to its negative impact on mental and physical health, and well-being 5,6. The prevalence of loneliness in older adults (≥60 years), assessed in 30 European countries, between 2000 and 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic), showed a high prevalence of loneliness among older adults in southern European countries (ranging from 15.7% to 18.7%); for Portugal, the prevalence based on single item was 14.9 (12.3-17.7) 7. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the population worldwide, particularly due to social distancing measures, lockdowns, and quarantine. Older adults were especially impacted since they are more vulnerable to the virus due to comorbidities 8,9. Therefore, loneliness levels have increased since the start of the pandemic 10,11. In the first few months, 25% of EU citizens reported feeling lonely more than half of the time, while in 2016, it was 12% 3.

Assessing loneliness with validated instruments is crucial for its surveillance, prevention, characterization, and intervention at individual and community levels 12. Two main methods have been used to assess loneliness: (i) validated loneliness scales, which measure the intensity of loneliness rather than its frequency, and (ii) self-rating scales, where respondents report the frequency of loneliness through a single-item question. Regarding the validated scales of loneliness, some are unidimensional (measure how lonely a person feels), while others are multidimensional (measure how lonely a person feels and what kind of loneliness they are experiencing). Some of the best-known scales worldwide are the UCLA loneliness scale 13 and the different revisions of this scale (ULS-4 14, ULS-8 15, ULS-6 16, RULS-8 17, and ULS-3 18); the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults (SELSA) 19 and the de Jong Gierveld scale 20. Regarding self-rating scales, the Campaign to End Loneliness 21 suggests three single-item questions: (i) Are you lonely? (ii) How often do you feel lonely? and (iii) During the past week, have you felt lonely? Some research has suggested that single items are more appropriate for an older age group experiencing cognitive decline or communication difficulties 21.

Overall, as people age, they become more vulnerable to loneliness, mostly because opportunities to socially interact and form relationships tend to diminish 22,23. Some factors contribute to that decrease: (1) the retirement process, which decreases the daily contact with co-workers; (2) physical frailty, which decreases the number of social interactions; and/or (3) the mourning of the loss of relatives. In addition, in Portugal, the emigration of the younger population and the decrease in fertility rates have made the older population more vulnerable to loneliness due to factors such as living alone, low income, and fragile informal networks 24.

Different instruments have been used to assess loneliness in the past decades; however, information about reliability and validation is dispersed. An analysis of the instruments validated for Portuguese older adults is useful to guide the selection of measures for research and clinical purposes. To our knowledge, this is the first review addressing the instruments in use to assess loneliness in Portuguese older adults. This scoping review aims to map the instruments validated for the Portuguese older population (≥60 years old) that assess loneliness and to identify their psychometric properties and the contexts in which they have been used. The results are expected to guide researchers and practitioners in selecting the best instrument to measure loneliness.

Methods

A protocol was developed using the framework proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute 25 and adjusted by the platform registration guidelines 26. The final version of the protocol is available in INPLASY2021100002 27. The research questions were defined according to the population, concept, and context (PCC) strategy: P, older adults aged ≥60 years; C, loneliness assessment instruments; and C, Portugal, including the community, intermediate care, long-term care, or acute care. The research questions were as follows: (1) What are the validated instruments for Portugal that assess loneliness in older adults? (2) What are the psychometric properties of these instruments? (3) In which contexts have these instruments been used?

The inclusion criteria comprised Portuguese population aged ≥60 years old (including Portuguese individuals living abroad); studies focusing on the development or psychometric evaluation of instruments, including cultural, linguistic adaptation and/or translation; studies reporting standardized measurement instruments with validation data; publications which can be read by the research team (Portuguese, English and Spanish); and articles published after 1978. This time period was adopted because the UCLA loneliness scale was launched that year 13. The exclusion criteria were as follows: studies not involving the Portuguese population (or including only non-Portuguese living in Portugal); sample only comprising participants <60 years old (studies for general populations are included if data for the group aged ≥60 years old are available); studies not assessing loneliness; studies reporting non-standardized measures; and protocols, letters, commentaries, books, posters, and conference abstracts.

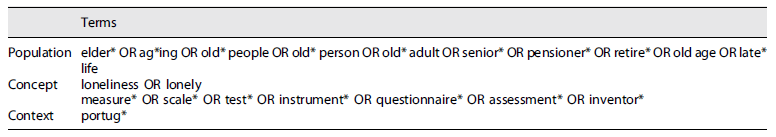

An initial search on MEDLINE (PubMed) and Scopus was undertaken to identify articles on the topic. The title, abstract, and keywords were analysed to find the words in the text that were used to build a good search strategy (Table 1). Published studies were identified in the following electronic databases: SciELO, PsycInfo, Scopus, MEDLINE (PubMed), MedicLatina (EBSCO), Nursing & Allied Health Collection: Comprehensive (EBSCO), and CINAHL (EBSCO). The source of unpublished studies/grey literature was RCAAP (Open Access Scientific Repositories of Portugal) through the research integrator of the libraries of the University of Aveiro. Searches were conducted from October to December 2021. The reference lists of the included studies were analysed to identify additional relevant studies.

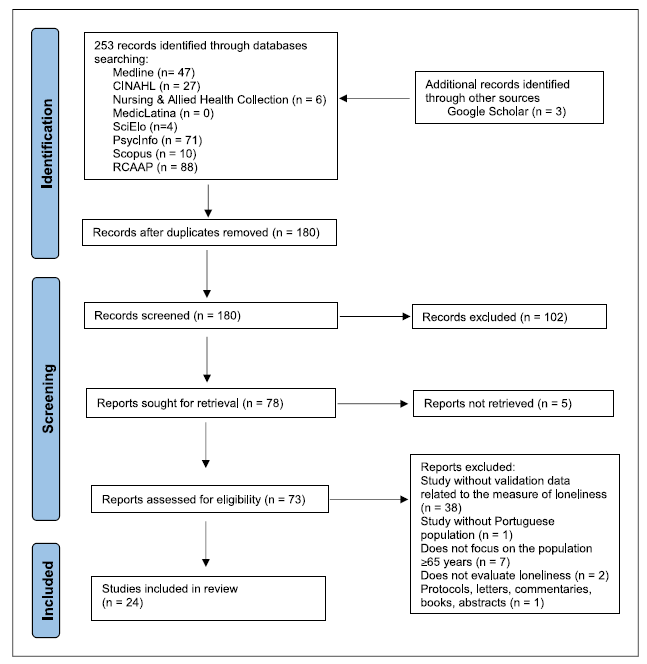

Following the search, all identified citations were collated into a spreadsheet (Excel version 2203) and duplicate entries were removed. Then, the titles and abstracts were analysed by two independent reviewers (R.C. and L.S.) for assessment against the inclusion criteria. Doubts were solved in a discussion with J.T. For the publications that remained after the search in titles and abstracts, the full article was retrieved and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Full-text studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Any disagreements were resolved through a discussion between R.C. and L.S., and if a consensus was not reached, the disagreements were resolved with a third reviewer (J.T.). The flowchart in Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics of identifying studies and selecting them for analysis according to PRISMA-ScR.

The researchers developed a data charting to determine which variables to extract according to the review questions. The data were extracted by R.C. and revised by J.T. and L.S. in an interactive discussion process. The data were structured into two types: (i) studies validating measures that assess loneliness in Portuguese older people and (ii) studies using instruments that assess loneliness in a sample of older Portuguese adults and report data on the instruments’ psychometric properties. The data extraction for articles that validated the measures included author, year of publication, instrument title and/or abbreviation, type of study (development and validation; translation, adaptation, and validation; validation to a new population), item generation, sample and context, administration method, description of items, scoring and interpretation, reliability, and validity. The data extracted for articles using instruments that assess loneliness comprised author, year, objectives, type of study, population/sample, instrument, context, main results, reliability, and validity. The draft data extraction tool was modified and revised as necessary during the extraction process. Any disagreements were resolved through team discussions. Data analysis followed a descriptive form to map the evidence according to the review questions; the main findings were addressed through a narrative review.

Results

In total, 78 records were retrieved, of which 24 full texts were included in this scoping review. Four articles validated instruments that assess loneliness in older Portuguese adults (Table 2). Twenty studies assessed loneliness in a sample of Portuguese older adults and report data on the instruments’ psychometric properties (Table 3).

Table 3 Studies using instruments that assess loneliness in a sample of older Portuguese adults and report data on the instruments’ psychometric properties

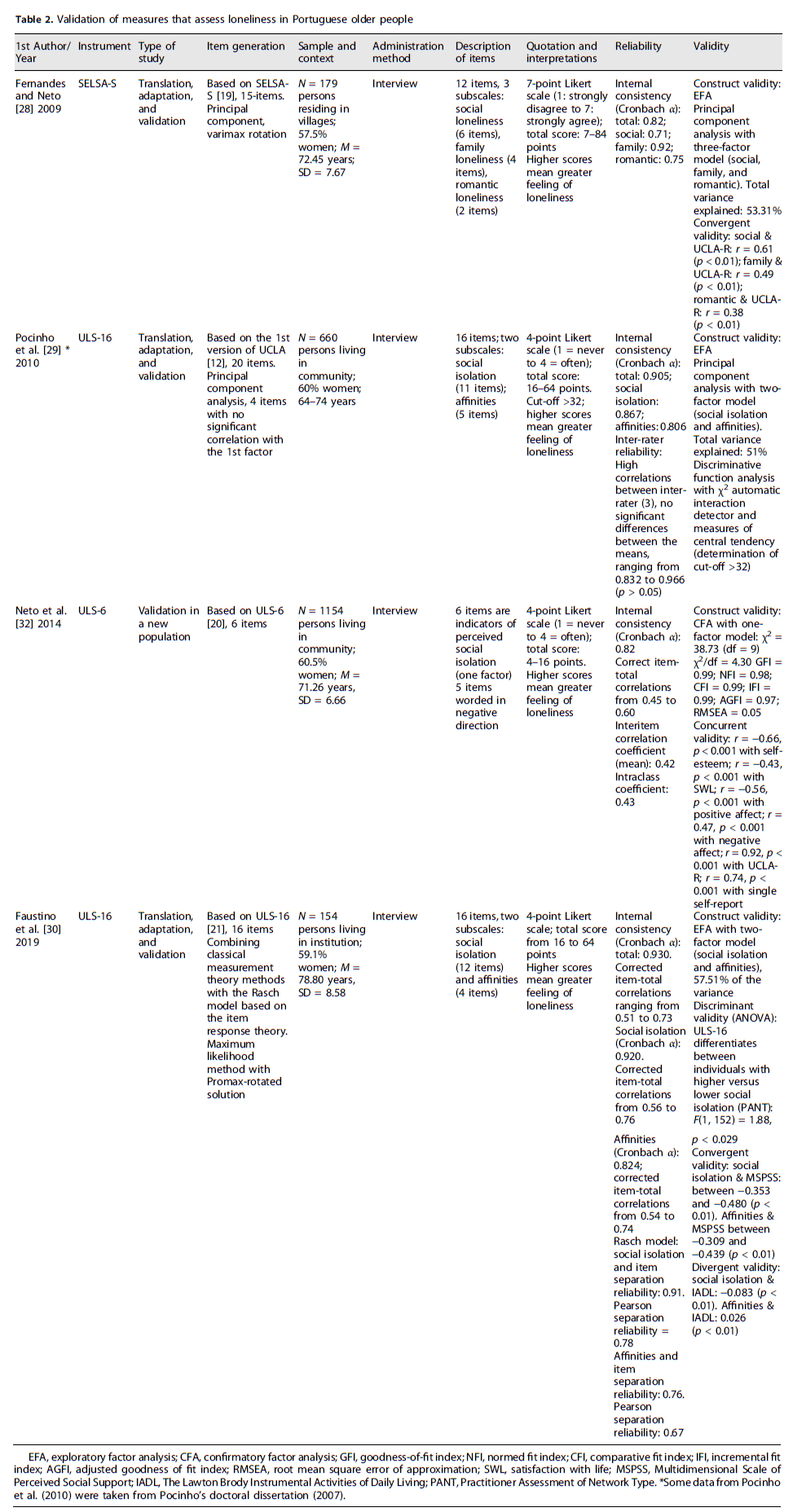

Validation of Measures That Assess Loneliness in Portuguese Older Adults

Four articles validated two instruments: SELSA-S and two versions of UCLA (16 items and 6 items).

Fernandes and Neto 28 validated SELSA-S by examining the construct validity using an exploratory factory analysis through principal component analysis with varimax rotation, comprising 15 items. A three-factor model was obtained (social, romantic, and family loneliness), explaining 53.31% of the total variance. Results from the convergent validity showed a positive moderate significant correlation between SELSA-S social subscale and UCLA-R (r = 0.61; p < 0.01) and the SELSA-S family subscale and UCLA-R (r = 0.49; p < 0.01) and a positive significant correlation between the SELSA-S romantic subscale and UCLA-R (r = 0.38; p < 0.01). Internal consistency was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha for global (0.82) and social (0.71), family (0.92), and romantic (0.75) subscales.

ULS-16 items were first validated by Pocinho et al. 29 based on Russel et al.’s 13 study on community-dwelling older adults; Faustino et al. 30 validated Pocinho, Farate, and Dias’s version for institutionalized older adults by combining the classical measurement theory methods with the Rasch model. Pocinho et al. 29 used principal component analysis with initial matrix and varimax rotation with normalization (total variance of approximately 51%). Internal consistency (reliability) was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.905). Inter-rater reliability (three ratters) was assessed to range from 0.832 to 0.966 (p > 0.05). Discriminative function analysis was performed (through ANOVA) using the χ2 automatic interaction detector. The results of this hierarchical model (which included the variables family relationship/support, polymedication, age, family typology, and recent losses) with the measures of central tendency were used to determine the cut-off of UCLA-16 (>32: higher scores suggesting higher feelings of loneliness). Faustino et al. 30 used the maximum likelihood method with a promax-rotated solution having a total variance of 57.51%. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was assessed as α = 0.930. Correct item-total correlations reliability was assessed, ranging from 0.51 to 0.73. It was performed with discriminant, convergent, and divergent validity. The discriminant validity was assessed with the social isolation subscale (PANT) and the convergent validity was assessed with the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) with significant results, which validate ULS-16 (PANT): F (1, 152) = 1.88, p < 0.029; social isolation and MSPSS between −0.353 and −0.480 (p < 0.01) and affinities and MSPSS between −0.309 and −0.439 (p < 0.01). The divergent validity was assessed with the Lawton Brody instrumental activities of daily living scale (IADL), which showed no significant Pearson correlations (social isolation and IADL = −0.083; affinities and IADL = 0.026).

Neto developed the ULS-6 initially with a sample of Portuguese adolescents 31. Later, the author aimed to obtain empirical evidence regarding the psychometric properties of ULS-6 in the older population 32. In the validation process, the test of dimensionality (hypothesized one-factor structure) was performed with confirmatory factor analysis. The results showed a good adjustment model (χ2 = 38.73 [df = 9; χ2/df = 4.30; GFI = 0.99; NFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; IFI = 0.99; AGFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.05). Neto 32 used other criterion-related validity through the correlation of ULS-6 and other scales. A negative and significant correlation was found between ULS-6 and self-esteem (r = −0.66, p < 0.001), ULS-6 and satisfaction with life scale (r = −0.43, p < 0.001), and ULS-6 and positive effect (r = −0.56, p < 0.001). The correlation between ULS-6 and negative effect was positive and significant (r = 0.47, p < 0.001). A very strong correlation (r = 0.92, p < 0.001) and a strong correlation (r = 0.74, p < 0.001) were verified between ULS-6 and UCLAR-R (long version with 18 items) and a single self-report (“Do you ever feel lonely?”). To test the reliability of ULS-6, Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.82); corrected item-total correlations, ranging from 0.45 to 0.60; the interitem correlation coefficient (0.42); and the intraclass coefficient (0.43) were used and demonstrated a sufficient level of homogeneity. These values confirm the internal consistency of ULS-6. ULS-6 comprises five items worded negatively and one item positively. To reduce response bias, the word “lonely” never appears in the scale.

In the four articles 28,30,32, SELSA-S, ULS-16, and ULS-6 presented satisfactory psychometric properties with a high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.82 to 0.93). In three studies 28,29,32, the target population comprised community-dwelling older adults (a total of 1,993 participants), while in one study 30, the target population was institutionalized older adults (154 participants). Therefore, only ULS-16 was validated for the institutional context.

Reliability was tested in all studies with Cronbach’s alpha to assess internal consistency. The Cronbach alpha values suggested good internal consistency (α = 0.8-0.9) in Fernandes and Neto’s study (SELSA-S) 28 and in Neto’s study (ULS-6) 32, both having a value of 0.82. Regarding the studies by Pocinho et al. 29 (ULS-16) and Faustino et al. 30, the results suggested excellent internal consistency (α > 0.9), with values of 0.905 and 0.930, respectively. Two studies 30,32 reported additional reliability tests through the correct item-total correlations: Neto reported results on interitem and intraclass coefficients and Faustino used the Rasch model based on the item response theory. One study 29 reported an additional reliability test through inter-rater reliability. Construct validity (exploratory factor analysis in SELSA-S and UCLA-16 [with a total of variance explained ≥50% and confirmatory factor analysis in ULS-6), convergent validity, or discriminate validity was tested in the four studies.

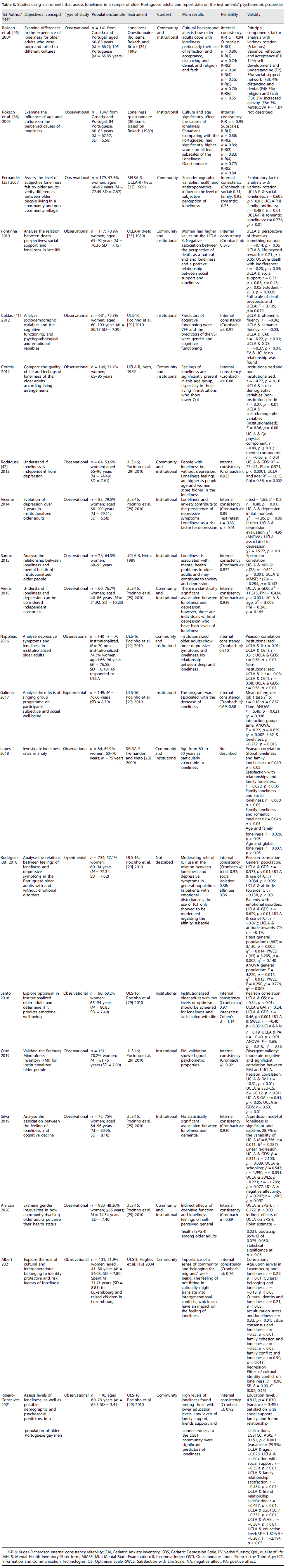

Assessing Loneliness in a Sample of Older Portuguese Adults and Reporting Data on the Instruments’ Psychometric Properties

Twenty studies focused on loneliness in the Portuguese older population (≥60 years old), whether in a community or institutional context and presented validation data. Details of the psychometric quality assessment of the instruments are presented in Table 3.

These studies used five instruments to assess loneliness: ULS-16 29, with 16 items, was used in 12 studies; UCLA-R 33, with 20 items, was used in 3 studies; the loneliness questionnaire 34 was used in 2 studies, one with 86 items and the other with 30 items; and SELSA-S 28, with 12 items, and ULS-3 18 with 3 items were used in one study each. One study 35 used two loneliness instruments: SELSA-S and UCLA-R. To our knowledge, 14 out of the 20 studies used instruments with previous validity and reliable data for the Portuguese older population (SELSA-S, ULS-16, and ULS-6).

Construct validity and internal consistency were the two most frequently reported measurement properties. Construct validity was assessed through confirmatory, exploratory, and divergent and convergent analyses, and internal consistency was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha. All publications reported construct validity (convergent, divergent, or structural), except one 36. The studies performed correlation, association, and mean difference analyses, which can contribute to providing information on the divergent and convergent validity of the instruments. Regarding convergent validity, the most used were correlation tests between UCLA and other scales/variables. The main constructs were depressive symptomatology (through GDS), indicating that it was positively and significantly correlated with loneliness 37,40; one study showed a very low negative correlation 41 and anxious symptoms (Geriatric Anxiety Inventory [GAI]), indicating in two studies a very low positive correlation 39 and moderate positive correlation 40; in another study, the correlation was very low and negative 41. Three studies reported results from the association between loneliness and depressive symptomatology 42,44.

Regarding internal consistency, one study 45 did not report results. The study 35 that used two instruments (UCLA-R and SELSA-S) showed the internal consistency of SELSA-S subscales (social: α = 0.71; family: α = 0.92; romantic: α = 0.75). The two studies that used the loneliness questionnaire 36,46 used the Kuder-Richardson scale to measure the internal consistency reliability, yielding an alpha value of 0.94 for the 86-item version and 0.95 for the reduced version. The remaining 17 studies reported internal consistency assessed by Cronbach’s alpha, with values ranging from 0.690 to 0.979. One study using UCLA 47 showed values between 0.69 and 0.88. The other 11 studies that used this instrument showed good internal reliability (α ≥ 0.89); the three studies that used UCLA-R also showed good internal reliability (α ≥ 0.872). The study that used ULS-3 showed acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.76).

Discussion

The findings highlight the validation of the following instruments for the older Portuguese population: SELSA-S 28 and two versions of UCLA: ULS-16 29,30 and ULS-6 32. ULS-16 (Faustino et al. 32 version) was the only one validated in the last 5 years. The ULS-6 was validated 8 years ago, while both SELSA-S 8 and ULS-16 (Pocinho et al.’s 29 version) were validated more than 10 years ago. It is important to perform validations for the current older population, considering the evolution of communities and societies. In addition, the use of further validation methods may be useful; for instance, the Rash analysis (allows the psychometric refinement of measures where respondents answer on Likert-type scales) and confirmatory factor analysis may reinforce the validation data 48.

ULS-16 showed good psychometric quality, with preliminary evidence of reliability and validity to assess loneliness in older adults. We found two studies with UCLA in two contexts (community and institutional). Further studies could include larger samples and differentiate cohorts of older adults, such as very old versus young older adults. Additionally, the validation in other contexts, namely health centres, would provide a reliable and validated measure for the setting of primary care and boost its clinical use by primary health care professionals. There are several reduced versions of UCLA not yet validated for the older Portuguese population, namely ULS-3 18, ULS-4 14, and ULS-8 15. The validation of these versions would make more instruments available and facilitate comparisons with populations from other countries.

The de Jong Gierveld scale is considered the most widely used, translated, and validated for several European countries but is still not validated for the older Portuguese population. It would be relevant to have this instrument validated for the Portuguese population to allow for international comparison. Furthermore, this is an important instrument because it can be applied as a unidimensional loneliness scale. However, the items were developed using Weiss’s distinction between social and emotional loneliness; thus, researchers can (depending on the research question) choose to use either the complete loneliness scale or the emotional (six items) and social (five items) subscales 49. Another scale that would be relevant to validate is the new ALONE scale 50 because it was validated to be used in clinical settings and is short (5 items). This scale allows the screening of older adults at risk of loneliness which could be followed by social prescribing of interventions that can help minimize loneliness 50.

Content validity is a fundamental aspect of instrument validity and forms the basis of other validity properties. Before testing the reliability and other types of validity of an instrument, it is critical to establish content validity following recommendations as part of a rigorous instrument development and validation process 51. However, few studies have presented information on translation and adaptation. Regarding construct validity, all studies used different techniques (convergent, divergent, and structural). In criterion validity, only Neto reported concurrent validity regarding ULS-6. Criterion validity is a fast way to validate data and a highly appropriate way to validate personal attributes (i.e., depression, strengths, and weaknesses) 52.

Regarding reliability, although the four validation articles showed internal consistency values, it is important to use other properties, such as test-retest reliability, and inter-rater and intra-rater reliability. However, none of these studies assessed test-retest and intra-rater reliability. One study tested inter-rater reliability. These three tests are important for assessing the agreements among the measures. Test-retest reliability allows the assessment of agreements among measures obtained by one evaluator that tests the same group of subjects at different times. Inter-rater reliability allows the assessment of agreements among the measures obtained by two different evaluators that test the same group of subjects. Intra-rater reliability allows the assessment of agreements among repeated measures obtained by one evaluator in the same group of respondents 53.

In the four validation studies, psychometric tests were performed with samples above 100 participants. Although there is no gold standard for the sample size to be used in developing a new instrument or testing an existing instrument in a different population, the main recommendation is at least 10 participants per item 54. In the studies by Fernandes and Neto 28, Pocinho et al. 29, and Neto 32, there was a ratio of more than 10 participants per item. In Faustino et al. 30, the sample size (n = 154) was slightly below the ratio of 10:1. Nevertheless, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin was 0.909 and the sphericity test showed values of X2 = 1408.26, p = 0.001, which supported the sample adequacy in the study.

Regarding the studies that assessed loneliness in Portuguese older adults presenting validation data, five instruments were used in 20 studies. Fourteen studies used instruments validated for the Portuguese older population (SELSA-S or ULS-16). The others used ULS-3, which was originally developed for older adults but, to our knowledge, does not have an adaptation to the Portuguese population. Some other studies used UCLA-R, which is applicable to the general Portuguese population but not specifically to the older population. The version for the general population was used, and then a validity analysis was conducted to assure the applicability to older adults. Nevertheless, validation is always recommended. It is important to adapt and validate the ULS-3 and UCLA-R to the Portuguese older population because UCLA-R is the most extensively used UCLA version 55, and ULS-3 is the shortest version of UCLA that can be used for telephone surveys 18.

Ten of these studies used the Pocinho et al.’s 29 ULS-16 version to assess loneliness in the institutional context. However, this validation was carried out in the community context. In the validation process, especially in factor analysis, sample selection can generate different factor models 56. Therefore, prior to using ULS-16 in the institutional context, it would be relevant to perform reliability and validity studies to ensure the consistency and accuracy of ULS-16 in this population. Additionally, there is already a ULS-16 validation (by Faustino et al. 30) for this context, which can be used to assess loneliness in institutionalized older adults.

Loneliness has been a public health problem for a long time, demanding assessment involving instruments with good psychometric proprieties, which allows to a better understanding of the phenomenon and, therefore, delineate intervention priorities and guidelines. Understanding loneliness in Portuguese older adults, after 2 years of heavy distancing measures implemented to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, demands instruments with good psychometric proprieties, which allow us to delineate intervention priorities and guidelines.

Conclusion

The findings in this scoping review mapped the validated instruments available for the Portuguese older population (≥60 years old). Findings may support practitioners and researchers to understand the instruments available and to choose the one/s that show better psychometric properties to use considering contexts and settings. Overall, ULS-16 shows good psychometric quality with preliminary evidence of reliability and validity. In both community and institutional contexts, ULS-6 and SELSA-S show satisfactory levels of internal consistency and validity. Future testing of the instruments in different contexts is required to update and accumulate psychometric evidence and expand its use in research and clinical practice. In addition, it is important to translate and validate other instruments to the Portuguese older adults population, namely de Jong Gierveld and UCLA-R (most used internationally), as well as the ALONE scale (new and brief).