Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by itching, skin dryness with scaling, erythema, edema, vesiculation, fissuring, and lichenification1. Disease severity is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the percentage of body area affected, the severity of signs and symptoms, and disease evolution2. Moderate to severe AD has a major negative impact on quality of life. In a study carried out in Portugal, 36% of patients with AD reported that their disease had a very significant or extremely significant impact on their lives3. These patients often have sleep disorders (34% of patients), anxiety, and depression, reporting disease aggravation after performing simple daily tasks such as bathing or playing sports3–5. In addition to its impact on quality of life, moderate to severe AD has high costs associated with lost productivity (absenteeism and presenteeism). In a situation similar to that of Portugal, in Spain, it is estimated that AD results in a loss of working days in 24.5% of cases6. This translates into an economic cost of €1057 per patient per year in severe forms of the disease, €538 per patient per year in the moderate forms, and €196 per patient per year in the mild forms6.

Since AD is a chronic disease that cannot be cured, its treatment involves strategies and therapies focused on minimizing the impact of the disease-associated symptoms. First-line therapy in patients with mild disease consists of general measures (including the daily use of emollients), topical corticosteroids, and/or topical calcineurin inhibitors7. In addition to these therapies, moderate to severe AD may require systemic therapies, such as ciclosporin, methotrexate, and oral corticosteroids, or other therapeutic alternatives, such as phototherapy, which can have significant adverse effects7. More recently, innovative therapies have been developed, including biological medicines and oral small-molecule drugs, which have revolutionized the treatment of this disease8,9. These have fewer adverse effects, resulting in an improvement in the patient’s quality of life, as well as an improvement in work and/or school productivity due to better management of the disease (fewer symptoms and fewer adverse effects).

Patients with mild disease are mostly followed up in primary care by their general practitioner/family doctor within the Portuguese National Health Service (Sistema Nacional de Saude - SNS), whereas the majority of patients with moderate to severe AD are followed up in specialized medical care, mostly in dermatology. Due to the high impact on patients’ quality of life, the dermatology capacity is critical and decisive in the disease management of AD patients9,10.

The main objective of this study is to characterize the current care capacity in dermatology (in both public and private settings), to assess its suitability to the needs of patients with moderate to severe AD, and to identify potential strategies to improve health care provided to these patients. This study explores the capacity of dermatology care in Portugal for patients with moderate to severe AD. It highlights patient needs and the obstacles and limitations facing the current service provision.The information and data for this study were reviewed by a group of experts in individual meetings. Finally, a consensus meeting was held with a panel of experts to discuss all the topics addressed and possible strategies or solutions to mitigate the main problems, particularly the use of the Portuguese public health service (SNS) or private setting for dermatology appointments. A final result is a comprehensive approach which enables better care provision to patients with moderate to severe AD in Portugal regardless of whether they are managed in the SNS or private setting.

Materials and methods

The analysis was conducted in three stages: (1) data collection; (2) individual interviews to validate the information; and (3) two consensus meetings with a panel of experts.

The literature review focused on analyzing the epidemiology of AD in Portugal, health care capacity in dermatology, impact on quality of life, and patients’ care needs, centering on patients with moderate to severe disease. The panel of experts included seven dermatologists and one pediatrician (with multidisciplinary experience in pediatric AD management), who were selected based on their experience in AD management, geographic distribution, private or public clinical practice, and their participation in publications related to AD in Portugal. The interview stage took place in September 2021 and comprised eight individual remote interviews. The aim was to validate data and identify additional relevant data sources (Table 1). The validated information was used to support a structured discussion at the consensus meetings held in January 2022 (Table 2). At this meeting, an agreement was reached on the epidemiology of AD in Portugal, the healthcare needs of these patients, and the current capacity of dermatology to support AD management. Based on the general agreement, the panel of experts discussed and agreed on potential strategies to address the current gaps in health care for AD.

Table 1 Dimensions of analysis, metrics, and criteria

| Dimensions of analysis | Metrics characterization and sources | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Prevalence (%)11-16 | Percentage in Portugal or comparable countries Resident population in Portugal11 According to the age ranges: Children (< 12 years old) Teenagers (12-17 years old) Adults (> 18 years old) |

| Incidence (%)17 | ||

| Analysis of capacity of dermatology care services in Portugal | Demand for AD health care services3 | Specialty: Dermatology National Continental Territory23 |

| Referring patients to the National Health Service | ||

| Annual production in dermatology18 | ||

| Territorial coverage of dermatology18-20 | ||

| Waiting time for a first consultation21,22 | ||

| Quality of life and care needs | Symptoms on quality of life3 | Patients with AD (includes patients with moderate to severe disease) |

| Reasons for AD patients use of the private care system3 |

AD: atopic dermatitis.

Table 2 Consensus meeting script

| Prevalence | What is the best estimation for prevalence of AD in Portugal? And in moderate to severe disease? |

| Health care needs | What is the best estimation for appointment needs in patients with moderate to severe AD? |

| Access barriers | What are the key barriers that affect the access of these patients to specialty care (in dermatology)? |

| Strategies and solutions | What are the possible strategies to improve access to advanced therapies in private sector? What are the other possible strategies? |

Results

To characterize the dermatology capacity in Portugal for AD patients, several dimensions were analyzed, including those related to AD epidemiology, estimated demand in public and private health care services, existing referral processes to access specialty care on the public health service, annual production in dermatology in the public sector, territorial coverage of public and private dermatology services and waiting times for a first appointment in dermatology in a public setting, and finally the impact of AD on patient quality of life and their needs.

Epidemiology

There are no studies evaluating the real prevalence of AD in Portugal but based on data from neighboring countries and expert consensus, there were estimated to be approximately 360,000 patients in Portugal (Table 3). This equates to approximately 3.5% of the population. The prevalence of AD varies significantly across age groups (≤ 12 years old, 13-17 years old, ≥ 18 years old), with estimations in the Portuguese population shown in Table 3. In Portugal, 20% of AD patients have moderate to severe disease16, which represents an estimated 70,000 individuals.

Table 3 Prevalence of AD patients per age in Portugal

| Resident population | Prevalence of AD | Patients with AD | Patients with AD moderate to severe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children (≤ 12 years) | 990,83611 | (11.0-15.5%)12 | 108 992-153 580 | 20.0%16 | 21,798-30,716 |

| Teenagers (12-17 years) | 617,28111 | (8.0%-9.0%)13 | 49 382-55 555 | 33.0%15 | 16,296-18,333 |

| Adults (≥ 18 years) | 8,759,64811 | (0.61%-2.64%)14 | 53 434-231 255 | 33.0%15 | 17,633-76,314 |

| Total | - | - | 211 808-440 390 | - | 55,727-125,363 |

AD: atopic dermatitis.

Additionally, AD incidence in patients < 18 years old is expected to continue growing. Epidemiologic studies between 1990 and 2010 in several European countries showed an increasing trend in AD17. Experts have justified these figures based on the increasing AD-associated risk factors, such as a more urban lifestyle, increased exposure to environmental pollution and other factors, such as hygiene habits, high stress, diet, etc.

Increasing numbers of AD patients and a greater awareness of the disease, and the need for treatment are placing more pressure on the SNS to keep up with the growing number of patients.

Analysis of the capacity of dermatology care services in Portugal

Demand for AD health care services in the public and private sector–most AD patients are followed and manage their disease in private settings, with only approximately 30% of patients being treated exclusively in public settings3. Typically, patients with moderate AD learn to manage their disease on their own, requiring fewer medical appointments. These patients are often followed in primary care in the public sector. In contrast, patients with moderate to severe disease need specialized care and more regular follow-up, relying on both public and private settings. In Portugal, the percentage of patients treated exclusively in private settings seems to decrease as disease severity increases3.

Experts agree that patients need to have regular appointments and access to advanced therapies. Patients with moderate to severe diseases that require advanced therapies are referred to public consultations to guarantee their access to treatment.

Referring patients to the SNS–access to advanced therapies is thus the main reason identified by the experts for referring patients with moderate to severe AD from private settings to the SNS. Experts analyzed the current referral process to public dermatology consultations and identified major limitations. In hospital triage upon referral to dermatology, moderate to severe AD is not classified as a “priority” or “high priority” disease in adults, leading to longer waiting times for a first consultation. Secondly, dermatology in public care includes the monitoring of patients with suspected oncologic cases, and therefore, AD patients have a relatively lower priority. Finally, this process often depends on the referral from public primary care to specialized care. Considering the low coverage of family doctors in primary care, AD patients often have limited access to dermatology care if not from private referral. To illustrate the issue, about 9 and 44% of doctors in general practice are between 61 and 65 and > 65 years of age, respectively23. Therefore, access to primary care is expected to worsen rapidly.

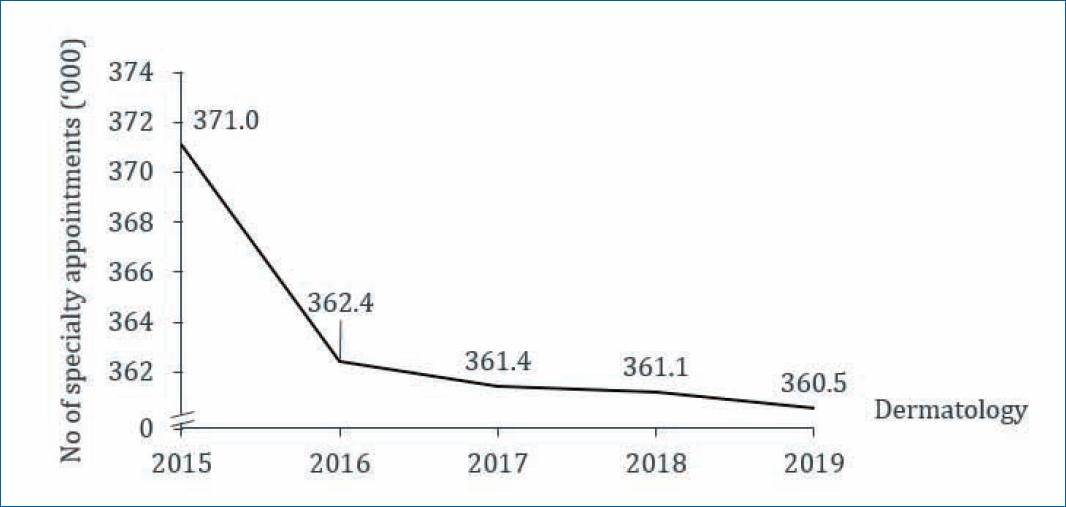

Annual production in dermatology–the number of dermatology consultations on the SNS decreased by 2.3% between 2015 and 2019 (−0.2% between 2018 and 2019)18. Considering the experts’ predictions, mild AD patients require between one and two dermatology consultations per year, while patients with moderate to severe AD require three to four per year. Therefore, in Portugal, moderate to severe AD requires an estimated 245,000 consultations per year (70,000 patients requiring ~ 3.5 consultations/year), which represents about 68% of existing18 public dermatology production. Therefore, the experts consulted agreed on the importance of the private sector in complementing the existing public dermatology production (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Evolution of production of specialties in dermatology in public health care (2015–2019, all diseases)18.

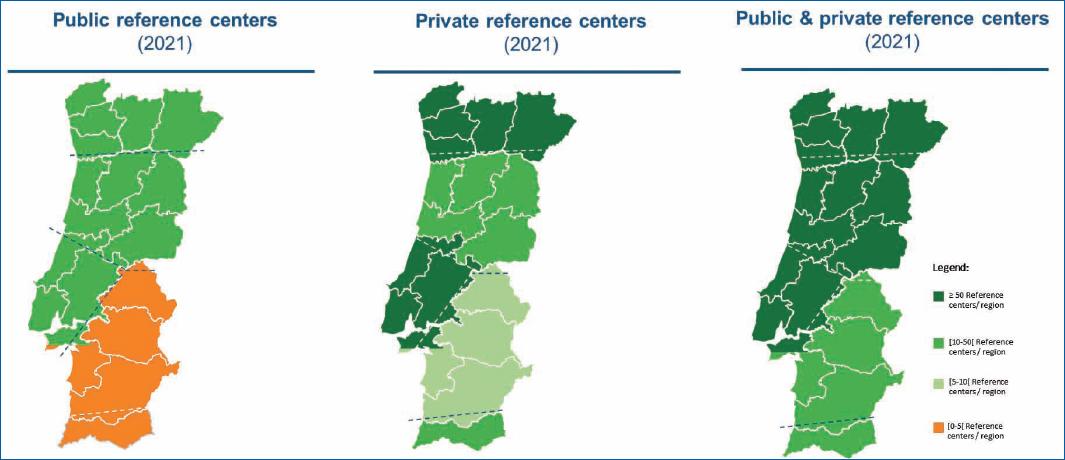

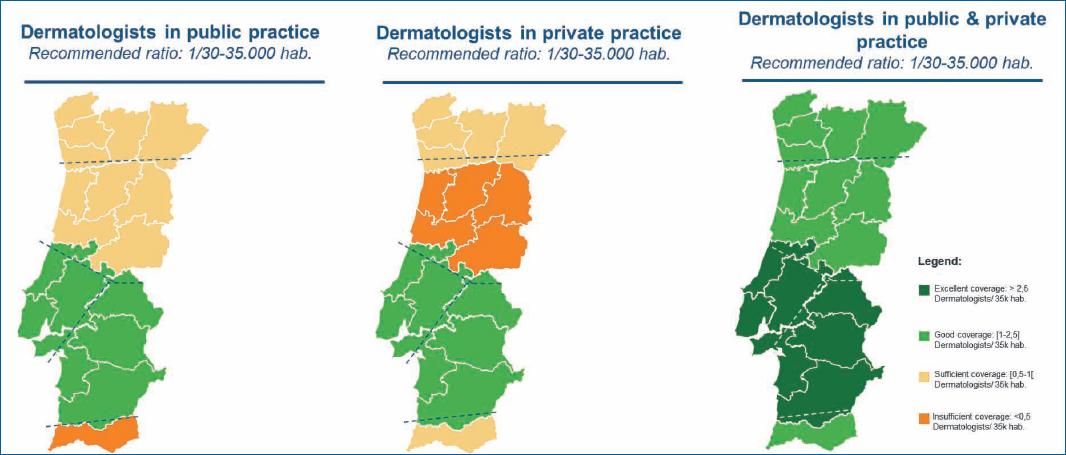

The territorial coverage of dermatology (institutions and specialists)–There are significant regional differences in the distribution of providers of dermatologic care, both in the SNS and private sectors. Private setting plays an essential role in complementing the SNS, namely mitigating the regional differences in coverage. Figures 2 and 3 18-20 illustrate the uneven territorial distribution in dermatology centers and specialists, respectively. When compared, the North and Center regions and the region of Lisbon have more resources in specialized care in dermatology than the southern regions. Reduced public coverage by centers specialized in dermatology was found in the Alentejo and the Algarve; some districts did not have public dermatology care services. Considering the territorial coverage of dermatologists, it is insufficient to meet the recommended ratio of 1/30,000-35,000 dermatologists for the population covered20.

This asymmetry reflects in poorer access to this specialty care by patients with AD. As a result, they are forced to travel longer distances to dermatology consultations, hampering disease management and equating to costs for patients and society as a result of higher absenteeism. The experts consulted indicated that private healthcare providers could play a key role in complementing the gaps in public dermatology capacity. However, this is not yet possible since physicians in private settings have a more limited therapeutic arsenal.

Waiting time for a first consultation–dermatology is one of the specialties that have the greatest difficulties in complying with the maximum guaranteed response time (MGRT) for first face-to-face consultations. In 2019, this goal was met in 51% of cases23. In the case of dermatology telescreening, the response time is ~ 70%19. The same trend can be found in performance data for previous years, such as 2018 in public dermatology care services24.

Additionally, dermatology patients classified as “normal” priority waited for an average of 236 days (9 months)21, while the maximum stipulated response time was 120 days22. Patients with a “priority” or “high priority” classification waited on average 40 days21, compared to the maximum response time of 60 days and 30 days, respectively22. A comparison with patient-reported data reveals that in private settings, patients waited on average 14 days for dermatology appointments3.

From the experts’ experience, AD patients are usually assigned a “normal” priority at hospital triage, even in moderate and severe cases. Moreover, experts considered that the 60-day waiting time established in the MGRT for a “priority” case could still be considered long for patients with more severe diseases.

The experts consulted believed the average 236 days waiting time for “normal” priority would result in the absence of adequate treatment due to lack of specialist assessment and may lead to a significant reduction in the quality of life of these patients, given the chronic and recurring nature of the disease, characterized by repeated cycles of exacerbation and improvement. In the absence of treatment in moderate to severe cases, patients remain in a serious clinical state until receiving specialized care.

Episodes of AD exacerbation are one of the main reasons why patients with moderate to severe AD go to the emergency room more often and opt for private care (21-35% of patients)3.

Quality of life and care needs

It is reported that moderate to severe AD affects patients’ quality of life significantly, with 34% of patients reporting sleep disorders, 33% anxiety, 27% difficulties in bathing, 19% difficulties in dressing and undressing, and 5.2% depression3. A total of 86% prefer private care as a result of shorter waiting times, and 49% prefer private care because of the possibility of choosing a specialist3. Moreover, from the experts’ experience, patients also resort to private care due to greater flexibility in scheduling appointments outside working hours and based on geographic proximity.

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrate that there are significant gaps in the management of patients with AD in Portuguese public health care. These gaps are of particular importance in moderate to severe cases of AD and include:

– Limitations in the existing referral of adult patients with AD to dermatology consultations in the public services.

– Territorial coverage of dermatology centers in the public service, with significant regional differences.

– Insufficient coverage of dermatologists in the public service to meet the recommended ratios.

– Long waiting times for first consultations in dermatology on the public service.

Considering the above limitations, it is of the greatest importance to define strategies that ensure AD patients can have access to continuous monitoring and treatment through a truly complementary healthcare network in dermatology, covering both public and private institutions. In this regard, equal access to advanced and innovative therapies for AD patients is the area in which private dermatology health care cannot truly complement the public health care system.

Special reimbursement and prescription regimens for innovative advanced therapies in the private health care system already exist in the Portuguese public health service, but they do not cover AD. One of the most innovative approaches was the development of Act 48/2016 on 22 March. This legislation provided the legal framework to support patients with conditions that have a high impact on their quality of life, such as plaque psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. This law enabled them to have access to innovative advanced therapies, regardless of the setting in which the patient was being treated.

A possible approach to improve AD patients’ access to advanced therapies, such as biological agents and small molecules, could be the extension of Act 48/2016 of 22 March to include AD. An alternative approach could be the creation of a similar new legal framework covering AD, recognizing specific features in the reimbursement and dispensing advanced therapies approved for the treatment of this condition. In this case, the competent authorities would have to define under which conditions these therapies would be available, as well as balance the severity of the disease with its impact on the patient’s quality of life.

These legal measures are likely to result in a positive impact by:

– Minimizing the impact of long waiting times on the quality of life of patients with moderate to severe AD.

– Eliminating barriers and inequalities of access, promoting patient access to similar therapeutic options regardless of being treated in public or private health care, in accordance with the provisions of Act 99/2022 (Article 3-A)25. With this legal framework, the inclusion of AD in a special prescription regimen becomes even more urgent, as it becomes the responsibility of the hospital’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee to define and approve protocols determining the criteria and conditions of use for these medicines, enabling the rigorous evaluation of these criteria according to the context and needs of the population.

Reducing the referral of patients managed in the private sector to dermatology consultations in the public health service, which is mainly justified to enable access to innovative therapies such as biological agents and small molecules.

Although this framework mitigates considerable limitations and barriers in public health care, particularly for patients with moderate to severe AD, the expert panel believed that strict dispensing criteria should be anticipated for the prescribing centers duly registered at the Directorate-General for Health, meeting national and international best practices for dispensing advanced therapies. These could be defined or revised by a group of experts, specialists, or medical societies selected on the basis of their high-level experience in this type of therapy.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the epidemiology of AD in Portugal and the current capacity of public and private dermatology care services to meet patient needs. The analysis addressed the use of public and private health care services by patients with AD, the adequacy of the referral process, which is essential to gain access to advanced target therapies, the capacity of the public dermatology services to manage the Portuguese population with AD, the differences in territorial coverage according to dermatologists and clinical centers in the public and private sectors and, finally, the waiting times to be treated with advanced target therapies. The results showed significant limitations and barriers to addressing patient needs, as well as important regional asymmetries.

The importance of continuous monitoring and treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD is critical to the management of this chronic disease.

In conclusion, we make recommendations to ensure continuity of care and equal care for patients with moderate to severe AD by their physicians, regardless of the setting. This would promote trust in the physician-patient relationship and improve adherence to therapies that prevent the progression of AD into more severe forms, which in turn translates into higher future costs and poor quality of life.

As a final remark, it is vital to respect a patient’s freedom of choice to be cared for by a specific healthcare professional of their choice. There is also insufficient justification for preventing eligible patients with moderate to severe AD from accessing innovative therapies in a timely way so as to avoid disease progression.