Introduction

Skin-related neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) remain a major public health challenge in Angola, prevailing in poor social settings with reduced access to healthcare, education, water, and sanitation services. Information on these infectious diseases is scarce and fragmented, calling for a knowledge review on their epidemiological and clinical dimensions to better identify corrective measures regarding case detection, control, and elimination strategies1-3.

Angola is a large country, with an area of 1,246,700 km2, divided into 18 provinces and 164 municipalities, located on the South Atlantic coast of West Africa, between Congo and Namibia, bordering the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) and Zambia to the east. Population estimate was 33.9 million in 2021, including 46% of children aged 0-14 years; an estimated 45% of people had access to health services and 42% to potable water in 20183.

The objective of this review is to document and analyze data collected from 2017 to 2021 by Ministry of health (MOH) as well as published information on the status of ten main skin-related NTDs.

Another purpose is to highlight the current and potential contribution of Angolan dermatologists to clinical, epidemiological, and educational activities to public health programs related to skin NTDs.

Methods

The following ten skin NTDs were included in the review: leprosy (Hansen's disease); lymphatic filariasis (LF); onchocerciasis; guinea worm disease (GWD or dracunculiasis); cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL); Buruli ulcer (BU); deep mycoses, including mycetoma, sporotrichosis and others; scabies; yaws (better known as “bouba” in Angola); and snakebites and envenoming.

This is a retrospective analysis of the documents and records collected from 2017 to 2021 by the National directorate of public health (DNSP), complemented by data on skin-NTDs from field investigations, geographical mapping, and other sources of information, including WHO reports.

Results

The 2017-2021 administratively reported cases of skin-NTDs are presented in table 1 2,3. Most were diagnosed on a clinical basis. Laboratory examinations such as microscopy of blood smears and of skin preparations stained with Giemsa, Ziehl-Neelsen procedure and/or other special colorations, cultures, and histopathological analyses of biopsy material were performed in a minority of cases, as functional laboratory facilities and histopathology services are inadequate outside of the most populated provinces, such as Luanda, Huila, and Huambo.

Table 1 Reported cases of skin-related neglected tropical diseases 2017-2021, National Directorate of Public Health

| S-NTDs | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Endemic areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leprosy | All 18 provinces (2021) | |||||

| – Newly detected cases | 605 | 847 | 721 | 422 | 797 | |

| – Rate/million pop | 20.31 | 27.49 | 22.66 | 12.84 | 23.90 | |

| – Cases under treatment | 1018 | 1070 | 1070 | 1870 | 1785 | |

| – Prevalence rate/million population | 34.18 | 37.73 | 33.62 | 56.90 | 53.00 | |

| –New child cases (% of new cases) | 35 (5.8) | 68 (8.0) | 116 (16.1) | 56 (13.3) | 93 (11.7) | |

| –New cases with G2D (% of new cases) | 98 (16.2) | 145 (17.1) | 112 (15.5) | 20 (4.7) | 187 (23.5) | |

| –Multi-bacillary new cases (% of new cases) | 578 (95.5) | 795 (93.9) | 637 (88.3) | 361 (85.5) | 681 (85.4) | |

| Onchocerciasis | 48 municipalities (29.3%) in | |||||

| – New cases | 603 | 238 | 288 | 838 | 1110 | 10 provinces (2021) |

| Lymphatic filariasis | 38 municipalities (23.2%) in | |||||

| – New cases of lymphedema/hydrocele | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | 12 provinces (2021) |

| Guinea worm (dracunculiasis) | 3 municipalities in Cunene province | |||||

| – New cases | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | (2018-2020) |

| Cutaneous leishmaniosis | Londuimbali municipality in Huambo province (2017) | |||||

| – PCR confirmed cases | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| – Suspected cases | 53 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Buruli ulcer | Mbanza Congo municipality in Zaire | |||||

| – PCR confirmed cases | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | province (2021) |

| Deep mycoses | Sporadic cases countrywide | |||||

| – New cases | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | |

| Scabies | Countrywide | |||||

| – Cases | 13,2747 | 52,983 | 54,996 | 15,738 | No data | |

| Yaws | Unknown current status | |||||

| – Cases | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Snakebites | Countrywide, data from 14 provinces | |||||

| – Cases | No data | No data | No data | 522 | 581 | |

| – Deaths | No data | No data | No data | 35 | 41 |

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests performed in reported and published cases of LF, BU, and CL were all carried out in foreign recognized laboratories. Rapid immunological screening tests to detect yaws (SD Bioline Syphilis 3.0 and dual path platform Syphilis Screen and Confirm assay) were used to test clinically suspected cases. The Alere™ Filariasis test strip (FTS) was used in LF mapping surveys and to monitor the qualitative detection of Wuchereria bancrofti3.

Leprosy (Hansen's disease)

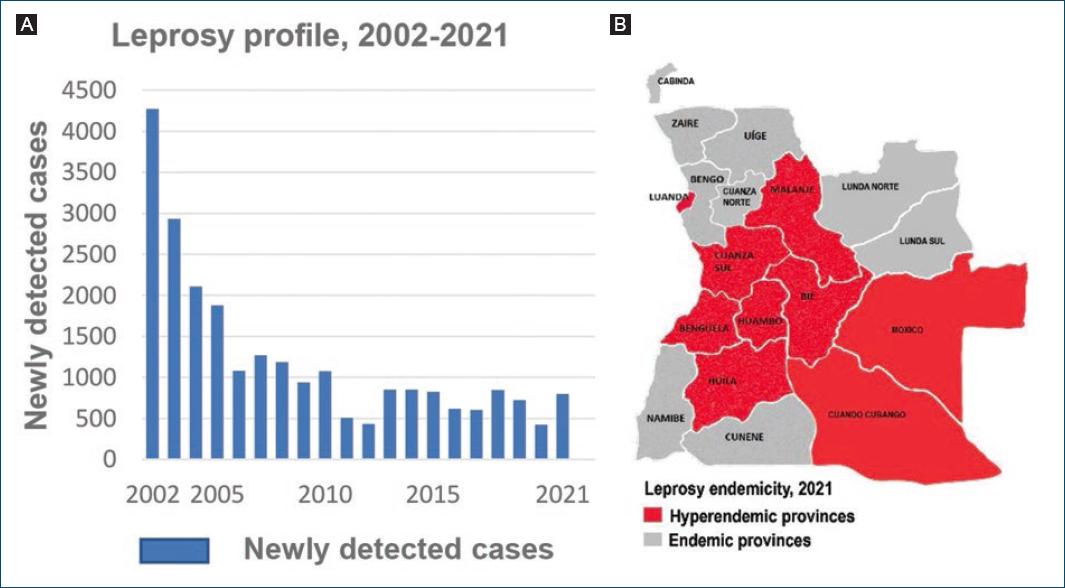

In 2005, the prevalence rate of leprosy level passed below the level of one case per 10,000, reaching the goal of “leprosy elimination as a public health problem”, as defined by the WHO4. As shown in figure 1A, the number of newly detected cases decreased from 4272 in 2002 to 431 in 2012, with yet a high proportion of new cases in children under 15 years (12.8%), and multi-bacillary cases (MB) (69.3%), suggestive of continuous disease transmission in affected communities5. From 2012 onward, the number of newly annually reported cases increased again progressively to 605 in 20176 and to 797 in 20217, accompanied by a concomitant increase in the proportion of new pediatric, G2D and MB cases (Table 1); 75% of all cases were males and 25% were females8; the disease was endemic in all provinces, with 82% of all reported new cases congregated in nine provinces, including Luanda8 (Fig. 1B).

Filariasis

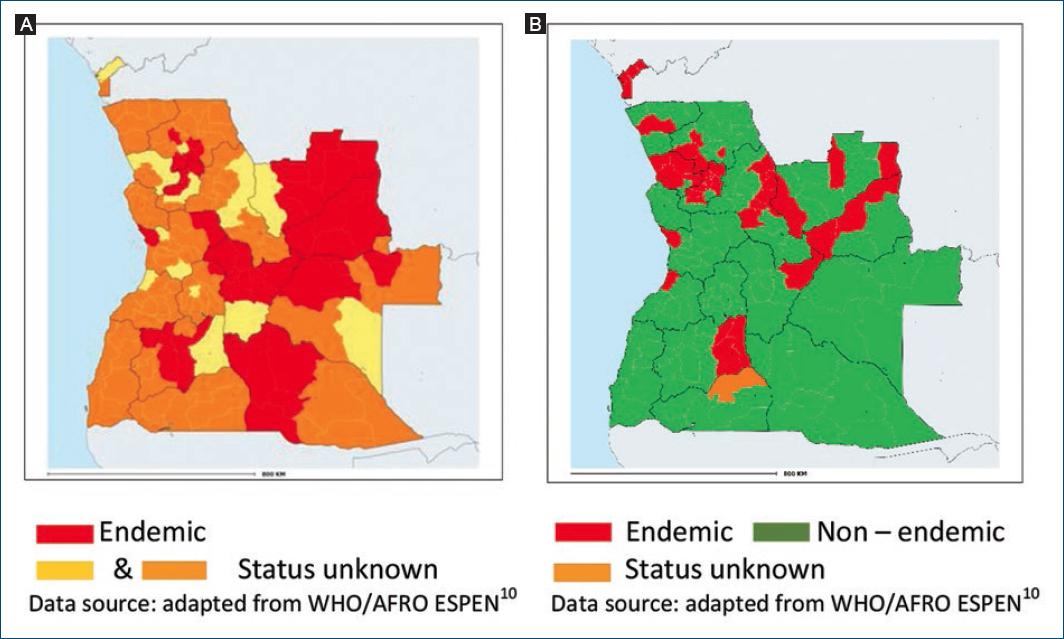

Notification of onchocerciasis is mandatory but most reported cases are not confirmed by microscopy of skin snip biopsies. The first mapping of onchocerciasis was performed in 2002 using the rapid epidemiological mapping for onchocerciasis (REMO) method assessing the number and percentage of villages with people presenting Onchocerca skin nodules in a given area9,10. In 2015, the REMO assessment was complemented by surveys using skin snip biopsies. In 2021, the WHO reported 48 municipalities (29%) as endemic, distributed in 10 provinces, with the highest prevalence rates in Bie, Huambo, and Cuando Cubango3,11 (Fig. 2A). The status of the remaining 116 municipalities is unknown and requires further investigations.

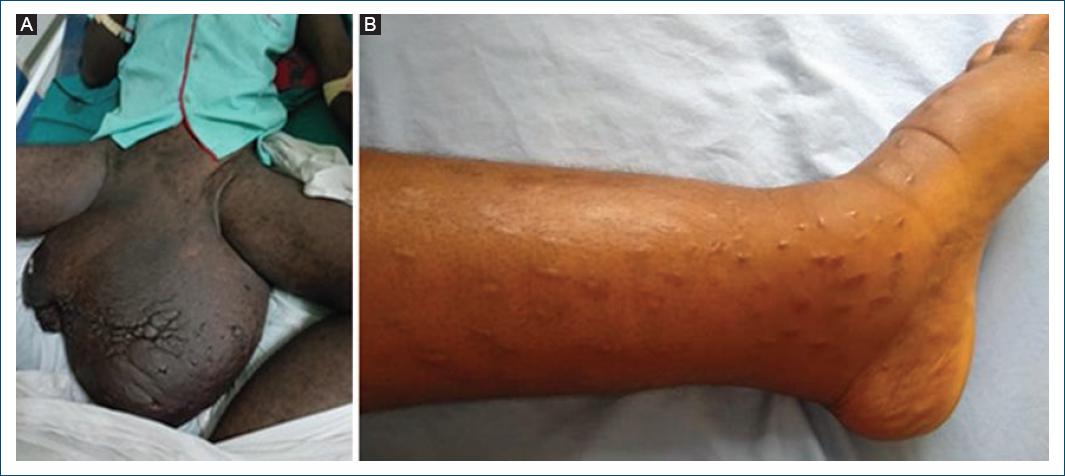

LF scrotal hydrocele and limb lymphedema are not subject to mandatory notification. National mapping of LF was carried out from 2015 to 2017 in three phases, using the FTS (Alere™). The 2021 WHO data showed LF endemicity in 38 municipalities (23.2%) distributed in 12 provinces (Fig. 2B), and a disease prevalence ranging from 1% to 12%. Onchocerciasis and LF were coendemic in 15 municipalities and 7 provinces3,11. In 2020, the WHO estimated the total population requiring mass administration of ivermectin and albendazole (IA) to be 3,819,439; and 33 of the 38 LF endemic municipalities had started to implement IA mass drug administration/MDA) programs12.

The prevalence of Onchocerca volvulus, W. bancrofti, and Loa Loa infections was also assessed in Bengo province in 2017 and 2020 with a combination of clinical, serological, and DNA diagnostics13,14. Overall, low levels of endemicity with variable overlapping distributions were observed in 22 communities. Onchocerciasis prevalence was 5.3% in eight communities and LF-related lymphedema and/or hydrocoele were found in 27 individuals (1.7%).

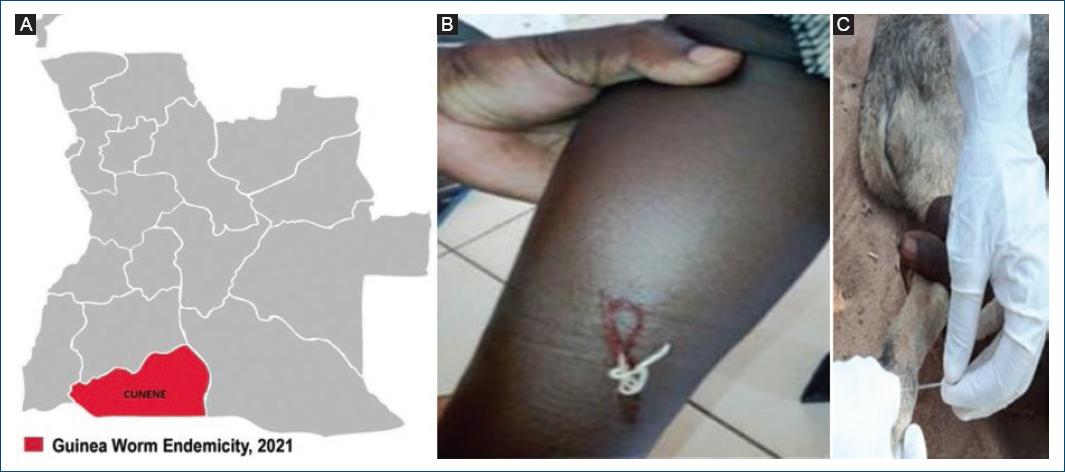

GWD or Dracunculiasis

Angola, not known for GW cases, reported from 2018 to 2020 three PCR confirmed cases of human GWD infection15. All cases were found in three chronically drought affected municipalities of Cunene province, bordering Angola with Namibia16 (Fig. 3A). The first case (Fig. 3B) was detected in 2018 through a nationwide GWD case search carried out during a national immunization campaign against measles and rubella17.

Figure 3 Guinea worm. A: cunene province, bordering Angola with Namibia. B: human GWD. C: canine GWD (back leg).

Alongside the reported cases of human infections, the detection in 2022 in the same province of eight cases of GWD infections in dogs (Fig. 3C) was a finding of particular importance3.

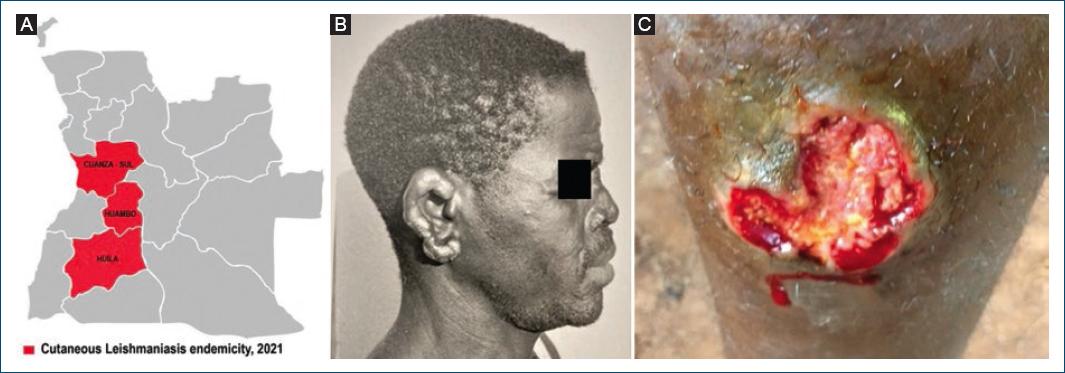

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

The first confirmed cases of CL in Angola were reported in 1969 by Bréchet at the Caluquembe missionary Hospital, in two patients hailing, respectively, from Huila and Cuanza Sul provinces18 (Fig. 4A). The patient from Cuanza Sul presented with multiple infiltrated lesions, nodules, and some ulcers, which were initially misdiagnosed and treated as atypical lepromatous leprosy, until the correct diagnosis of CL was clearly established by histopathological examination of the ear lesion (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4 Cutaneous leishmaniasis. A: provinces of Cuanza-Sul, Huíla, and Huambo. B: case from Cuanza Sul showing multiple ear infiltrations and nodules. C: ulcer in a case from Londuimbali, Huambo province.

In 1994, Jimenez et al.19 published the case of a 26-year-old man with no history of travel outside Angola who consulted and presented in Spain with typical symptoms of visceral leishmaniasis. The parasite was isolated and biochemically characterized as Leishmania infantum. According to Jimenez et al., this was the first report of L. infantum identified in Africa, south of the equator.

Between 2017 and 2019, 71 clinically suspected cases of CL were identified through active community case detection in the municipality of Londuimbali in Huambo province20. Most of the lesions observed (88.7%) in those cases were round or oval painless ulcers located in exposed areas (Fig. 4C), showing a reddish and firm base, often covered with crusts, with elevated and well-defined borders. Material from three biopsies was sent for molecular analysis to the Lisbon Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; two of the samples, from patients aged 18 and 26 years, were reported as PCR positive for Leishmania spp. DNA21. Laboratory investigations were not carried out in other clinically suspected cases.

Dogs are known as a main reservoir for human infection. In 2014, a serological and molecular survey of Leishmania infection was carried out in 103 dogs in the capital city of Luanda, by Vilhena et al.22. One autochthonous dog was found PCR positive for L. infantum, Canine leishmaniosis (CanL).

Buruli ulcer

In 1998, Bär et al.23 published the first reported Angolan case of BU, a 2.5-year-old boy from Bengo province (Fig. 5A) referred to Germany for diagnosis and treatment of severe malnutrition (Kwashiorkor) and of a large thoracic chronic ulcer. Mycobacterium ulcerans was identified from the ulcer by histological examination, PCR, and culture.

In 2003, 27 cases were reported among Angolan refugees24, diagnosed and treated at the Kimpese Hospital, Bas-Congo region, DR Congo. In 2018, a joint Angolan MOH/WHO team went on a fact-finding mission and reported the presence in the same institution of nine patients with BU, hailing from the northern provinces of Angola25 (Fig. 5A). Following the resolution of the internal conflict in 2002, the cross-border movement of goods and people between Angola and the DR Congo, still highly endemic to BU26, returned to a complete normalization.

In 2018, another report26 described two laboratory- confirmed cases, most likely acquired in Kafufu/Luremo villages located in the Malange province (Fig. 5A), along the Cuango river bordering North and East Angola with the DR Congo. These patients were living close to potentially contaminated aquatic environments, where artisanal alluvial mining activities are widespread, a factor considered as a risk factor for acquiring BU26,27.

Figure 5 Buruli ulcer endemicity, 1998-2021. A: Bengo, Uíge, Malange, and Zaire provinces where cases have been reported. B and C: cases from Zaire province, 2021.

In 2021, a MOH/WHO team, including a dermatologist, carried out a cross-border investigation in three border municipalities of Zaire and Uíge provinces, to actively search for cases of BU, leprosy, yaws, GWD, and African Human Trypanosomiasis. The mission detected a high number of common dermatoses, a case of leprosy and three autochthonous new BU cases in Mbanza Congo municipality, Zaire province (Fig 5A-C), all confirmed by PCR28. Angola was recognized in 2021 by the WHO as a new endemic country for BU.

Deep fungal infections

The epidemiology of these infections is poorly known due to weak laboratory services and lack of mandatory notification. Sporadic cases of mycetoma, chromoblasto-mycosis, sporotrichosis, and African histoplasmosis – occasionally associated with HIV/AIDS (Fig. 7B) – occur countrywide and often end up referred at an advanced stage for diagnosis and treatment to provincial hospitals and/or dermatology services29.

Scabies

Scabies is widespread in Angola (Table 1) but largely underreported and its real burden and distribution is largely unknown. Subnational data show many cases and frequent outbreaks reported in southern provinces, in areas particularly affected by drought and poverty. Scabies is the most common skin NTD diagnosed in dermatology outpatient services29, often associated with bacterial infection (Fig. 6A) and, in crusted scabies cases, with HIV/AIDS (Fig. 6B and C).

Yaws/Bouba

Angola is among the countries known to have been endemic for yaws in the 1950s, but its current status is unknown30. In 2021, an integrated skin NTD survey, including a search for yaws, was carried out in the northern provinces of Zaire and Uíge, combining clinical examination and the use of rapid screening tests in 76 suspected cases. None tested positive for yaws27.

Snakebite envenoming

In 2020 and 2021, a total of 14 provinces reported, respectively, 522 and 581 cases of snakebites with 35 and 41 deaths (6.7%/7.1%) (Table 1). Most cases were notified in northern and central provinces, namely, Uíge, Cabinda, Cuanza Norte, Cuanza Sul, and Benguela. No single case was notified in the capital city of Luanda. Under-reporting of snake bite incidence and mortality is common.

Discussion

Poor community knowledge on skin NTDs, late or missed diagnoses by health workers and limited access to laboratory confirmation of suspected cases are key challenges to overcome. At a time of renewed national and international efforts to control and eliminate skin-NTDs1,3, there is a dire need to improve knowledge on their burden and geographical distribution, by improving integrated surveillance, field surveys, and clinical investigations.

Dermatologists are key actors in fighting the neglect affecting skin-NTDs, offering expertise in the differential diagnosis of skin lesions such as discolored patches, nodules, and ulcers, facilitating the access to specific laboratory examinations, and helping in managing rare and/or difficult cases (Fig. 7A and B).

Since 2002, a growing number of national dermatologists have been trained locally and abroad, reaching a total of 37 in 2021, distributed in six provinces31. Some are already engaged in contact tracing, integrated clinical surveys, and diseases monitoring as well as capacity building and community mobilization activities (Fig. 7C).

Strengthened laboratory services including SOPs, direct microscopy, improved access to rapid tests, and PCRs are essential to confirm suspected cases, as the clinical diagnosis of skin-NTDs can be challenging, particularly for early-stage lesions1,32.

The collection of quality data on skin-NTDs, on which programmatic decisions should be based, is a well-recognized challenge. For a number of reasons, most data set are incomplete and fragmented. Mandatory notifications, required currently only for leprosy and onchocerciasis, should include ideally all skin-NTDs. According to the national epidemiologic bulletin33, only 79.6% of the expected provincial reports were received at the central level (DNSP) in 2021. Most data entries and analysis at the periphery are still paper-based, leaving ample room for mistakes and omissions.

The recommended WHO digital data platform “district health information system version 2”1 is being tested for leprosy, but not yet in routine use3. Its accelerated introduction should be given special attention to improve qualitatively and quantitatively the registration and monitoring of skin NTDs and to streamline the use of data for integrated program planning and implementation.

Disease mapping is a powerful tool to understand and monitor the geographic distribution of skin-NTDs, helping to orient integrated program planning, training of health workers, field investigations, treatment strategies, and drug's logistic, including anti-venom sera. Our data show significant geographic variations of skin-NTDs endemicity, ranging from a single province for GWD (Fig. 3A), to all provinces for leprosy (Fig. 1B). Multiple skin-NTDs are coendemic in many communities, municipalities, and provinces.

As observed in other countries6, the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the functioning of health services and public health programs, leading in 2020 to a reduction in the number of newly detected and reported skin-NTD cases (Table 1).

Skin-related NTDs, and leprosy in particular, have historically been studied and managed in Angola by leprologists and public health specialists through scientific missions. The “vertical” control program with leprosaria and mobile teams, established in 1958, was integrated in 2002 in the primary health-care system34 with positive results (Fig. 1A). Leprosy services were however later negatively impacted by dwindling clinical and program management expertise as well as funding, a trend favorably compensated by the expanding number of trained dermatologists31.

The persisting low-grade transmission of leprosy following its “elimination as a public health problem” calls meanwhile for further epidemiological and clinical investigations to detect where and why the elimination process is not moving forward. The relatively high proportion of G2D in newly detected cases reflects a delay in disease detection, resulting from low community awareness, delay in seeking care, weak active case finding and contact tracing, and/or limited capacity of the health system to early recognize leprosy6. Furthermore, in 2021, Angola's rates of new cases detection (23.09/million population), disease prevalence (53.00/million), new cases in children below 15 years (5.96/million), and new cases with G2D (5.41/million) were much higher than the respective rates for the African Region (18.01/million: 24.3/million; 4.34/million; 2.78/million)7.

Angola is considered by the WHO as a priority country for onchocerciasis and LF control and elimination12, but available data and studies are scarce and limited to monitor the burden of those diseases. LF is an avoidable, debilitating, disfiguring vector-borne disease, caused by W. bancrofti infection. Most infections occur during childhood and are initially asymptomatic. Scrotal hydrocele and limb's elephantiasis (Fig. 8A and B) are the visible clinical consequences of the chronic lymphatic vessel damage. Late diagnosis and treatment of these conditions are common. As an example, the 16-year-old girl shown in (Fig. 6B) presented early signs of lymphedema at the age of 12, and was treated for various conditions, including with traditional skin scarification, until a dermatologist made 4 years later the correct – laboratory confirmed – diagnosis of LF infection.

GWD, a crippling parasitic disease today on the verge of global eradication, was highly endemic in 20 countries in the mid-1980s. As a result of extensive and sustained control and elimination activities, only 15 cases were globally reported in 2021, including eight cases from Chad, one from Ethiopia, two from Mali, and four from South Sudan35.

While Angola was declared by the WHO in 2020 as a newly endemic country for GWD, neighboring Namibia has never been endemic and has been certified free of the disease in 199915. The two countries have set a good example of active cross-border collaboration for GWD case detection, surveillance, and follow-up15-17.

The detection in 2022 in Cunene province of eight cases of GWD infections in dogs, despite the implementation of all classical public health control and elimination strategies, set a particular challenge regarding the elimination of the disease in humans. A similar situation has been observed in Chad and Mali, where enhanced access to safe drinking water, education, surveillance, case containment, vector control, and monetary incentives for reporting cases have failed so far to prevent the circulation of Dracunculus Medinensis in dogs35.

While visceral and CL are endemic in North, West, and East Africa, very little is known about the transmission of the disease in Angola and other Southern African countries36. Canine leishmaniosis, a global zoonosis acting as a reservoir for human infections, is endemic in more than 70 countries in Europe, North Africa, Asia, and America, but information on its status in Southern Africa is very limited22. Further epidemiological and clinical investigations are required to better define the burden and distribution of CL in Angola.

First described in Australia in 1948, BU is an infection of particular importance in West and Central Africa25,37. BU is caused by M. ulcerans, an environmental bacterium producing the mycolactone toxin causing extensive tissue damage and inhibition of the immune response. The exact mode of transmission of M. ulcerans remains uncertain. BU starts clinically with a papule, nodule, plaque, or edematous lesion that eventually progress to a chronic indolent necrotizing disease of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and sometimes bone. Atypical forms can be confounded with other causes of skin ulcers and PCR testing is thus required to confirm the clinical diagnosis32.

Yaws, or bouba as known locally, is a non-venereal treponemal infection affecting mostly children under 15 years of age, caused by Treponema pallidum ssp. pertenue, leading to skin, bone, and cartilage lesions. Despite its currently unknown status, yaws should not be forgotten as its endemicity persists in the neighboring DR Congo and in the Congo Republic. Further investigations, especially in border municipalities, are required to detect its eventual presence in Angola especially in poor communities living at the “end of the road,” far from health services30.

Although Scabies and other ectoparasitosis have been added in 2017 by the WHO to the list of skin-related NTDs, theses common diseases are not yet formally integrated into the national NTD control program. Formal assessments of the local burden of scabies will allow to better identify the areas which would benefit of Ivermectin MDA. While the management of scabies is relatively simple and inexpensive, the access to quality medications is limited in many peri-urban and rural areas. A potential impact on scabies of Ivermectin currently given in mass drug administration (MDA) programs to control filariasis in endemic municipalities3,12 would deserve further studies.

Snakebites incidence in Angola is unknown, but probably high if we consider available data from DR Congo, where between 120 and 450 bites/100,000 inhabitants/year are recorded38. According to Ceriaco and Marques39, more than 120 species of snakes have been identified so far in Angola, including 34 potentially harmful to humans. The big vipers belonging to the Bitis species (Fig. 9A), spitting Naja nigricollis, and Mamba (Dendroaspis) species are reported as those biting most frequently, causing often severe skin lesions or fatal envenomation38. Beside systemic manifestations, local pain and lesions such as swelling, blisters, bleeding, and tissue necrosis are common (Fig. 9B). Dermatologists tend to see few snakebites as many cases either do not reach health facilities, or are referred directly to emergency surgery or medicine services.

Conclusion

Except for yaws – whose status is presently unknown but which should not be forgotten – all skin NTDs included in our review remain endemic locally or countrywide. As observed for leprosy, BU, CL, and GWD, elimination of those diseases as a public health problem does not warrant total interruption of transmission with time.

Epidemiological searches carried out in recent years have revealed unknown foci of BU, CL, and GWD.

The search and detection in dogs of GWD and leishmaniasis are of critical importance, given their known implications as reservoir for the transmission of those diseases to humans.

Leprosy remains endemic in all provinces with, since 2012, a stagnant elimination process requiring special attention. Interest and investment in operational research are essential.

The incorporation of CL, yaws, deep fungal infections, scabies, snakebites, and envenoming in the national NTD master's plans should lead to a better assessment of the burden and distribution of those diseases and improve case management.

As stakeholders of the coalition working for the control and elimination of skin NTDs, Angolan dermatologists save wasted resources caused by missed and late diagnosis of skin NTDs. They are called on to support more actively integrated approaches related to advocacy, disease surveillance, field investigations, and capacity building activities40,41.