Introduction

Vitiligo is a common disorder of pigmentation that can occur at any age and affects both genders nearly equally1. It is a multifactorial disorder having a complex pathogenesis for which multiple theories have been put forward, out of which the autoimmune theory is the most widely accepted2. Vitiligo can be classified as generalized, localized, segmental, or non-segmental. Rare clinical variants include trichrome, quadrichrome, pentachrome, red, and blue vitiligo3. The disease is usually slow and progressive having relapsing and remitting course along with exacerbations that might correlate with triggering events such as trauma (Koebner’s phenomenon). Treatment of vitiligo remains challenging for a dermatologist despite the availability of various therapeutic modalities which makes it a cause of great psychosocial stress to the patients4,5.

It is important to assess the severity of disease as it affects the psychological well-being of patients. The vitiligo area scoring index (VASI) is a quantitative score that uses hand units to quantify the proportion of vitiligo involvement6. Previously, there was no specialized quality of life (QOL) evaluation instrument for vitiligo; hence, it was assessed using non-disease specific scores7-10. Lately, evidence correlating vitiligo to various psychological issues proves it to be more of a psychosocial disorder affecting QOL, than merely a cosmetic concern8,9,11,12. Hence, a vitiligo-specific tool, vitiligo quality of life (VitiQoL), was developed13. It is an objective, vitiligo-specific assessment of disease state, burden, and treatment result for patients that is supported by disease-specific items derived from thorough open-ended patient interviews, clinician input, and a literature review14.

In this study, we have attempted to use the vitiligo-specific questionnaire (VitiQoL) to sight impact of the disease on QOL among patients with diverse demographics.

Methods

The study was initiated after obtaining ethical clearance from the ethics committee of the institute. A total of 108 patients of vitiligo attending the department of dermatology in a tertiary care hospital were included in this cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study after obtaining informed consent. The study was conducted over a period of 2 years. The study population included clinically diagnosed cases of vitiligo above the age of 18 years. Dermoscopy was used to confirm the clinical diagnosis of the patients. Patients with other disorders and disabilities associated with social stigma were excluded from the study. A detailed history including the name, age, gender, marital status, occupation, duration, onset, progression, treatment history, and other relavant data was recorded. Thorough assessment covered skin type, region of involvement, and vitiligo type (acrofacial, segmental, focal, or universal). The severity of illness was determined by VASI scoring, and its relationship with VitiQoL scores was evaluated.

Study measurement tools

VASI score is a quantitative score used for the evaluation of the severity of vitiligo. The degree of residual depigmentation is expressed as: the depigmented area surpasses the pigmented area at 100% depigmentation; at 50% depigmentation, the depigmented and pigmented regions are equal; at 25% depigmentation, the pigmented area exceeds the depigmented area; and at 10% depigmentation, just specks of depigmentation are present6. VASI of each body site (hands, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities, and feet) is calculated and then, cumulative body VASI is calculated using the following formula (range of 0-100):

VASI = Σ (all body sites) (hand units) × (residual depigmentation).

VitiQoL, proposed in 2013 by Lilly et al., is a disease-specific score used to measure concerns specific to the disease over a period of last month. It is based on three factors, namely, stigma, participation limitation, and behavior14. The score comprises 15 questions with a Likert scale of seven points (0-6) in which the total scores range from 0 to 90. Higher scores indicate a poorer QOL.

The English version of the VitiQoL questionnaire was translated into Punjabi language by a bilingual dermatologist. Backward translation of this questionnaire was done by another bilingual dermatologist and reviewed by the previous translator to ensure that the questions conveyed the same meaning. The content validity of both the forward and backward translations was discussed by two evaluators who were experts in vitiligo and were also bilingual (fluent in English and also native Punjabi speakers). No questions were added or removed from the original version and score ratings also remained the same in the Punjabi version. Patients were then asked to fill the translated questionnaire for the assessment of the QOL. The Punjabi version of VitiQoL has been attached as a supplementary file.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA for Windows) version 26 software. Numbers and percentages were used to describe qualitative data. Descriptive statistics, mean, and standard deviation were calculated for the quantitative data. Pearson correlation coefficient was used for the assessment of the correlation between QOL score, that is, VitiQoL, and vitiligo severity score, that is, VASI. Independent t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used for comparison of the demographic profile. Probability value p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

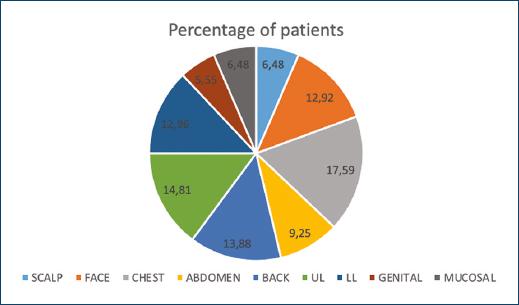

The study enrolled 108 patients (53 females and 55 males), with a mean age of 39.89 ± 14.37 years. The disease was most commonly observed in the age group of 40-49 years (36.72%) with mean duration of 2.2 years from the beginning of lesions. Maximum number of patients belonged to Fitzpatrick skin type 4 (69.12%) followed by 3 (37.8%), and positive family history among first-degree relatives was seen in 29 patients (31.32%). According to the marital status of the patients, 48 were married whereas 53 were single and seven were divorced. The most prevalent occupational group observed was that of laborers (33.48%) followed by students (32.4%), household workers (24.84%), semiskilled workers (15.12%), skilled workers (6.48%), and unemployed (4.32%). While 55.08% of patients had both exposed and non-exposed sites involved, 42.12% had lesions on non-exposed sites, and 19.44% on exposed sites only. The involvement of different sites in the study population is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1 Involvement of various sites in the study population-scalp (6.48%), face (12.92%), chest (17.59%), abdomen (9.25%), back (13.88%), upper limb (14.81%), lower limb (12.96%), genital (5.55%), and mucosal (6.48%).

With regards to disease severity, mean VASI score in this study was 13.26 ± 9.12 and higher values were seen in patients with disease duration of < 3 years (15.06 ± 10.86), those who had positive family history among first-degree relatives (14.21 ± 11.48) and were unemployed (17.35 ± 2.26). Similarly, higher VASI scores were demonstrated among patients with skin type V (18.67 ± 12.92), had lesions on the exposed sites (14.17 ± 11.8), and had patches involving the lower limbs (17.43 ± 8.19). Mean VASI scores observed were almost alike in both genders (males: 13.49 ± 10.15; females: 13.02 ± 8.10). Similarly, nearly equal values of mean VASI were observed in patients of different marital status (divorced: 13.79 ± 3.90; single: 13.09 ± 9.47; married: 13.37 ± 9.48). Of all the above values obtained, none of these was statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1 The correlation of VASI score with various demographic variables

| VASI | n | VASI mean | Standard deviation of VASI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| F | 53 | 13.02264 | 8.103042 |

| M | 55 | 13.49498 | 10.151652 |

| Age | |||

| 18-29 | 29 | 13.35793 | 10.954816 |

| 30-39 | 23 | 12.92496 | 7.639786 |

| 40-49 | 34 | 11.76794 | 6.488887 |

| 50 | 22 | 15.80273 | 11.403364 |

| Duration of disease | |||

| < 3 | 46 | 15.06609 | 10.869080 |

| 3-6 | 25 | 12.64800 | 4.703092 |

| 7-12 | 18 | 8.33278 | 5.457519 |

| 13-15 | 7 | 13.36571 | 9.308494 |

| > 15 | 12 | 14.96950 | 11.601466 |

| Family history | |||

| Positive | 29 | 14.21034 | 11.487202 |

| Negative | 79 | 12.91549 | 8.208034 |

| Marital status | |||

| Divorce | 7 | 13.79429 | 3.900576 |

| Single | 53 | 13.09566 | 9.470319 |

| Married | 48 | 13.37071 | 9.482691 |

| Occupation | |||

| Student | 30 | 10.58347 | 6.152763 |

| Labour | 31 | 15.70290 | 9.655232 |

| Household worker | 23 | 13.90391 | 11.209264 |

| Semiskilled | 14 | 12.09071 | 4.175003 |

| Skilled | 6 | 11.61000 | 8.444875 |

| Unemployed | 4 | 17.35250 | 20.260318 |

| Skin type | |||

| Type III | 35 | 13.12029 | 8.594867 |

| Type IV | 64 | 12.58006 | 8.766884 |

| Type V | 9 | 18.67667 | 12.929084 |

| Sites | |||

| Exposed | 18 | 14.17056 | 11.800257 |

| Covered | 39 | 13.58615 | 8.785275 |

| Exposed + covered | 51 | 12.69596 | 8.543971 |

| Individual sites | |||

| Scalp | 7 | 9.12700 | 3.541248 |

| Face | 14 | 12.85714 | 5.145439 |

| Chest | 19 | 13.30158 | 8.977349 |

| Abdomen | 10 | 17.24286 | 4.121850 |

| Back | 15 | 14.81067 | 7.569624 |

| UL | 16 | 9.61900 | 4.296506 |

| LL | 14 | 17.43571 | 8.193508 |

| Genital | 6 | 12.82167 | 7.023351 |

| Mucosal | 7 | 12.94714 | 7.334989 |

VASI: vitiligo area severity index.

Overall, the mean VitiQoL score of our study population was 25.71 ± 14.60, with statistically significant lower mean VitiQoL scores observed in males (24.53 ± 10.822) as compared to females (29.89 ± 12.57; p = 0.019). Similarly, higher statistically significant VitiQoL scores were observed in the age group of 18-29 years (31.64 ± 18.76; p = 0.022), who had lesions on the exposed sites (28.94 ± 12.25; p = 0.039) and among divorced patients (31.43 ± 11.60; p = 0.019). Higher scores were observed in patients with skin type V (33.67 ± 17.45), had lesions on the face (31.36 ± 21.82), and mucosal lesions (29.00 ± 16.62). The scores were highest in those who were unemployed (32.50 ± 25.56) and laborers (28.43 ± 16.10) as compared to other occupational groups, though not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2 The correlation of vitiligo quality of life score with various demographic variables

| VitiQoL | n | VitiQoL mean | Standard deviation of VitiQoL | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| F | 53 | 25.53 | 13.827 | 0.899 |

| M | 55 | 25.89 | 15.576 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18-29 | 29 | 25.52 | 16.311 | 0.181 |

| 30-39 | 23 | 23.87 | 12.282 | |

| 40-49 | 34 | 23.29 | 10.777 | |

| > 50 | 22 | 31.64 | 18.766 | |

| Duration of disease | ||||

| < 3 | 46 | 28.39 | 16.420 | 0.104 |

| 3-6 | 25 | 24.40 | 12.261 | |

| 7-12 | 18 | 18.06 | 8.235 | |

| 13-15 | 7 | 25.29 | 18.373 | |

| > 15 | 12 | 29.92 | 15.030 | |

| Family history | ||||

| Positive | 29 | 26.45 | 16.832 | 0.754 |

| Negative | 79 | 25.44 | 13.910 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Divorce | 7 | 29.43 | 11.603 | 0.762 |

| Single | 53 | 25.83 | 15.188 | |

| Married | 48 | 25.04 | 14.677 | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Student | 30 | 22.90 | 12.775 | 0.485 |

| Labour | 31 | 28.32 | 16.109 | |

| Household worker | 23 | 27.17 | 17.536 | |

| Semiskilled | 14 | 24.50 | 7.003 | |

| Skilled | 6 | 19.00 | 6.197 | |

| Unemployed | 4 | 32.50 | 25.567 | |

| Skin type | ||||

| Type III | 35 | 26.31 | 16.403 | 0.191 |

| Type IV | 64 | 24.27 | 13.061 | |

| Type V | 9 | 33.67 | 17.450 | |

| Sites | ||||

| Exposed | 18 | 25.94 | 17.254 | 0.983 |

| Covered | 39 | 25.97 | 15.399 | |

| Exposed + covered | 51 | 25.43 | 13.391 | |

| Individual sites | ||||

| Scalp | 7 | 27.14 | 20.416 | 0.192 |

| Face | 14 | 31.36 | 21.823 | |

| Chest | 19 | 28.00 | 14.380 | |

| Abdomen | 10 | 20.10 | 9.386 | |

| Back | 15 | 28.00 | 13.867 | |

| UL | 16 | 18.25 | 5.859 | |

| LL | 14 | 28.14 | 13.917 | |

| Genital | 6 | 17.67 | 3.615 | |

| Mucosal | 7 | 29.00 | 16.623 |

VitiQoL: vitiligo quality of life.

The highest mean VitiQoL score was seen in questions 1 and 9 of the questionnaire while the lowest mean scores were observed in questions 11 and 12. Similarly, the comparison of mean VitiQol scores among individual domains of the questionnaire demonstrated higher values among “limited social participation” and “stigma” domain in the female gender and in the patients aged 18-29 years, while higher values among the questions pertaining to the “behaviour” domain were observed in patients with skin type V and in those who had lesions on the exposed sites (Table 3).

Table 3 The effect of various variables on individual domains of vitiligo quality of life questionnaire

| Variables | Limited social participation | Stigma | Behavior | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 3.58 | 1.72 | 4.63 | 1.36 | 3.95 | 1.91 |

| Female | 4.12 | 1.41 | 4.96 | 1.28 | 3.29 | 1.40 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18-29 | 3.17 | 1.23 | 4.12 | 1.75 | 3.11 | 2.03 |

| 30-39 | 2.83 | 1.84 | 3.90 | 1.97 | 2.74 | 1.06 |

| 40-49 | 2.42 | 2.92 | 3.47 | 1.03 | 3.29 | 1.73 |

| > 50 | 2.85 | 1.05 | 3.92 | 1.39 | 3.30 | 1.29 |

| Skin colour | ||||||

| III | 3.68 | 2.95 | 2.83 | 1.95 | 3.15 | 2.01 |

| IV | 3.03 | 2.04 | 2.85 | 2.53 | 3.92 | 2.28 |

| V | 3.62 | 1.94 | 2.79 | 1.73 | 4.13 | 1.53 |

| Patches exposure | ||||||

| Exposed | 3.72 | 1.92 | 2.90 | 1.39 | 3.60 | 1.74 |

| Non-exposed | 3.38 | 1.06 | 3.15 | 1.03 | 3.14 | 1.05 |

| Both | 3.94 | 2.02 | 3.07 | 1.86 | 3.36 | 1.96 |

SD: standard deviation.

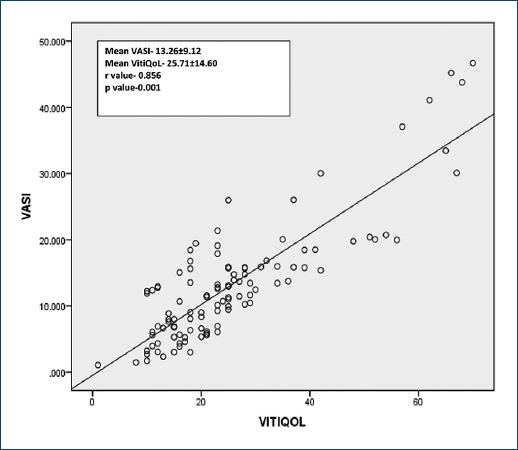

Figure 2 demonstrates the correlation of VASI score (13.26 ± 9.12) with VitiQoL score (25.71 ± 14.60) in which a very strong correlation was found between the two scores (r = 0.856 and p < 0.001).

Discussion

As a consequence of the high prevalence of vitiligo among various global races and the social stigma attached with it even among people of high economic status, there is an overwhelming impact on QoL and psychosocial component in the patients suffering from the disease. Despite the fact that India has the highest prevalence of the disease, there is a paucity of studies on the association of QoL indicators in vitiligo with disease activity and area scores in Indian patients15. In this particular study, though there was no significant difference among the mean VASI scores between males and females, the mean VitiQoL scores were significantly higher among females as compared to males, statistically (p < 0.05). This is similar to an earlier study done by Hedayat et al.13 thereby implicating that the disease has more influence on the QoL in females. However, it is in contrast to previous studies which demonstrated that the psychological impact of the disease remains the same irrespective of the gender16-18. This contradiction can be attributed to the cultural variations among individuals belonging to different regions in which the studies were carried out.

Similarly, other demographic variables that demonstrated such statistically significant higher VitiQoL scores, and thus, poor QOL due to vitiligo, were individuals in the age group of 18-29 years, divorced patients, and those who had patches on the exposed body parts. All these before mentioned results were consistent with studies done prior on QOL in vitiligo using other scores7,8,14,19.

The appearance of patches has been reported as grounds for divorce in many individuals as in our study20,21. Contrarily, in a study, conducted by in Saudi22, the QOL of married people was affected as much as that of single individuals. This difference could be explained by the firm and false belief about the contagious nature of the disease in developing countries like India due to lack of education. This fact is further supported by the higher values of VitiQoL score obtained in unemployed patients and laborers as compared to skilled individuals, though not statistically significant.

Overall, the mean VitiQoL scores were higher in questions 1 and 9, and lowest in questions 11 and 12 of the questionnaire, thereby indicating the fear of facing the society due to massive psychological impact on the diseased individuals. Among individual domains of VitiQoL questionnaire, the females and patients aged 18-29 years were found to have more limited social participation and stigma associated with the disease. On the other hand, the behavior domain was more affected in individuals who had skin type V and those having lesions on the exposed sites only. It is worth mentioning that the present study’s greater participation limitation scores contradict the majority of previous researches13,19,23. This disparity in participation limitation might be due to increased aesthetic expectations from women and those in the young age, which make these individuals unable to carry out day-to-day and recreational endeavors as freely as other individuals due to the superstitions associated with the disease. This inability to interact with others leads to solitude, overthinking, concern, embarrassment, and humiliation which adds to the stigma associated with the disease. In a similar manner, this relatively poor QoL in skin Type V and in the individuals having lesions on the exposed sites can be explained by the societal pressure of age old beauty standards that forces these affected persons to resort to techniques of camouflage to hide their patches, which in turn, leads to emotional breakdown and behavioral alterations13,19,23-25.

Furthermore, in the present study, it was observed that VitiQoL score had a statistically significant strong correlation with VASI score (p < 0.001, r = 0.856), which strikingly implies that higher the disease severity, more the impact on QoL. Several studies done before the present study have demonstrated this association of QoL scores with area severity scores10,13,16,17 but none of this showed such a remarkably strong correlation between these two variables.

Limitations

The study was a based on the questionnaire and did not include any control group. Another limitation of the study is the lack of psychiatric evaluation, such as inclusion of anxiety and depression scores. Moreover, it was conducted in a hospital and hence, extrapolating this data to the community level may not be reflective of the real burden of the disease.

Conclusion

Despite several limitations, our study demonstrated association of the body surface area score (VASI) of vitiligo with disease-specific QoL score (VitiQoL). The study highlights the efficacy and superiority of vitiligo-specific QoL measures over previous scores which lacked disease-specific parameters, thereby emphasizing the importance of assessment and timely screening of patients of vitiligo for psychological impairment with the help of such questionnaires as it as essential part of disease management.