Introduction

Deglutition or swallowing is a primary function that encompasses the processes by which food is transformed and transported to the oesophagus. It is a complex and precise neuromuscular mechanism that allows nutrition and prevents food from inappropriately accessing the airway. Clinical evaluation of swallowing is complemented by videofluoroscopy, which offers a dynamic assessment of deglutition and reveals clinically occult information.1

This article reviews the normal deglutition mechanism, presents the imaging protocol used in our institution and summarizes key imaging findings in normal videofluoroscopic swallowing studies (VFSS).

Epidemiology of oropharyngeal dysphagia and indications for VFSS

Dysphagia is a commonly reported symptom with an estimated prevalence of around 15% in the community-dwelling elderly.2 Oropharyngeal dysphagia may lead to malnutrition, dehydration and aspiration related respiratory infections, with a negative impact in quality of life and increased mortality.3,4

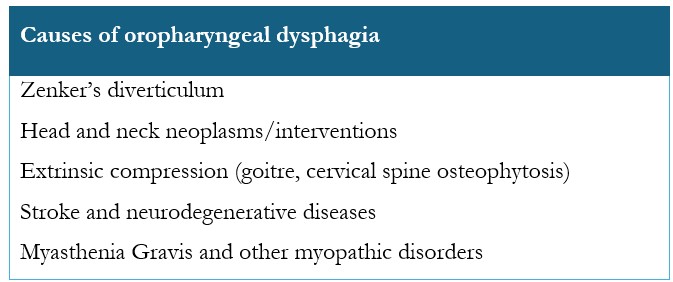

Oropharyngeal dysphagia may arise from a range of causes, such as anatomical/structural abnormalities, neurological conditions or myopathic disorders, and the most common aetiologies are summarized in Table 1.

VFSS is a valuable tool that provides anatomical and functional assessment of the structures involved in swallowing. Assessment of aspiration risk is a primary clinical application, with additional indications outlined in Table 2.

Relevant anatomical and functional concepts

The oral cavity, pharynx and oesophagus form a continuous channel that processes and transports food. Each compartment plays a separate function but cooperates in a tightly coordinated mechanism during swallowing.

The oral cavity serves as the entryway to both the digestive and respiratory tracts. It is bounded anteriorly by the lips, laterally by the buccinator muscles, superiorly by the hard and soft palates, inferiorly by the tongue and the floor of the mouth, and posteriorly by the oropharynx.

Food is contained in the oral cavity by the combined action of facial and oral muscles: the orbicularis oris and buccinator muscles prevent anterior and lateral spillage of boluses; and the velolingual valve - formed by opposition of the tongue to the soft palate - may transiently restrict the posterior communication with the oropharynx to prevent posterior bolus leakage.

The coordinated mechanical and chemical actions of teeth, masticatory and tongue muscles and salivary glands prepare boluses for transport to the oropharynx.8,9,10

The pharynx transports food to the oesophagus and air to the larynx. Its muscular layer is composed of an outer sleeve of intrinsic constrictor muscles - superior, middle and inferior - that contract sequentially to propel food through the pharynx, while the inner sleeve of intrinsic longitudinal muscles work with the laryngeal muscles to elevate and shorten the pharynx and close the entrance to the airway. The pharynx is divided into three parts:10,11,12

The nasopharynx is limited anteriorly by the choanae, laterally and posteriorly by the pharyngeal walls, superiorly by the skull base and inferiorly by the soft palate muscles. Under normal conditions, the nasopharynx is not involved in deglutition. During swallowing, the soft palate elevates and presses against the posterior pharyngeal wall, forming the velopharyngeal valve and preventing food from entering the nasopharynx and nasal cavity.

The oropharynx is bounded laterally and posteriorly by the pharyngeal walls, anteriorly by the base of the tongue and inferiorly by the valleculae and superior surface of the epiglottis. The epiglottis is a pear-shaped cartilaginous structure that closes the larynx when food is present in the pharynx. The valleculae are two small cup-shaped potential spaces bounded anteriorly by the tongue root and posteriorly by the base of the epiglottis.

The hypopharynx extends from the pharyngoepiglottic folds to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage, where it connects to the cervical oesophagus. It communicates anteriorly with the larynx through the laryngeal inlet and is separated from it by the aryepiglottic folds. Two posterolateral recesses are identified to either side of the laryngeal inlet, the piriform sinuses.

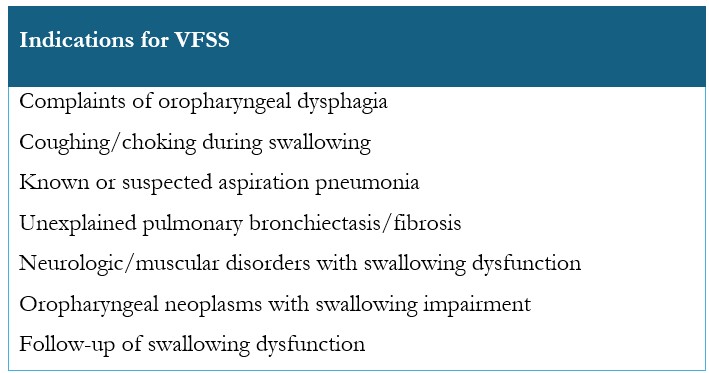

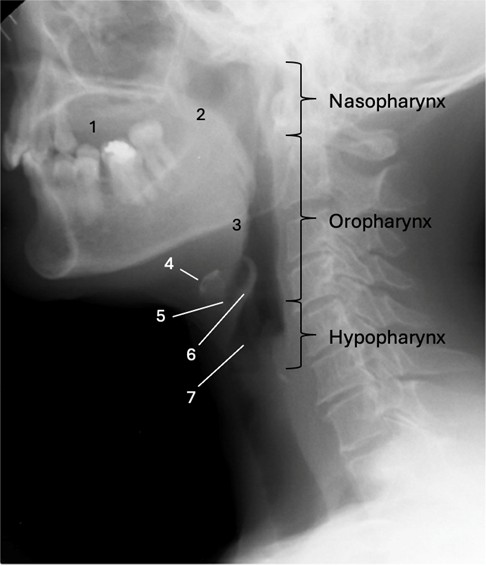

The radiographic anatomical landmarks are labelled on the lateral view in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Radiographic anatomical landmarks on lateral view.1 - oral cavity; 2 - soft palate; 3 - base of the tongue; 4 - hyoid bone; 5 - vallecula; 6 - epiglottis; 7 - laryngeal vestibule

The transition between the hypopharynx and the cervical oesophagus is marked by a region of increased luminal pressure known as the upper oesophageal sphincter, which is primarily composed of the cricopharyngeal muscle. Superior and posterior to it, between the oblique and transverse fibres of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, there is an area of anatomical significance called Killian’s dehiscence - an area of focal weakness where pulsion diverticula may arise (Zenker’s diverticulum). A second point of weakness is also recognized, located laterally and inferiorly to the cricopharyngeal muscle, where the less frequent Killian-Jamieson diverticula may develop.10

Physiology of deglutition

Deglutition is generally divided in two stages:

- Oral phase, which is voluntary and encompasses all processes before the boluses reach the oropharynx. It can be further subdivided in preparatory and propulsive phases;

- Pharyngeal phase, an involuntary phase that comprises the transport of boluses from the pharynx to the oesophagus and prevents aspiration of food to the airway.

Despite this theoretical division, deglutition is a dynamic process, and events may not be strictly sequential. Different studies13,14,15,16 have shown that food consistency plays a role in determining the organisation of the stages of deglutition and two physiological models based on the impact of food consistency have been proposed:17

Four-stage model: the deglutition of liquid boluses tends to be sequential, with the different stages of deglutition following each other chronologically. Bolus formation of liquids occurs in the oral cavity and propulsion to the pharynx does not occur before swallow onset.

Process model: chewed solid food may be actively transported from the oral cavity to the pharynx up to 10 seconds before swallow onset, a process known as stage II transport and that results in pharyngeal aggregation of boluses.14 This means that, under normal circumstances, swallowing of solid food is a non-sequential event and that oral and pharyngeal phases may occur simultaneously. Additional studies have shown that this phenomenon can also occur with biphasic boluses or during continuous ingestion of liquid boluses.16,18

Exam Protocol

In ideal circumstances, VFSS are performed by a multidisciplinary team composed of a radiologist, a speech-language therapist and a radiology technologist. In this setting, the patient may undergo simultaneous clinical and radiological evaluation, specific manoeuvres may be attempted during the examination to minimize dysphagia and the risk of aspiration, and dietary recommendations can be provided.

VFSS are performed in a seated or standing position. Elderly patients who usually wear dentures should keep them on during the study to replicate normal swallowing conditions. To minimize radiation exposure during the study, cooperative patients are instructed to hold the boluses in their mouth until prompted to swallow.

The examination is typically conducted using a single-contrast technique, as the primary focus is on the dynamic assessment of swallowing. Contrast material is administered orally, and barium contrast agents are favoured owing to its enhanced conspicuity and superior safety profile when small amounts are aspirated. In our institution, we use barium sulphate at a concentration of 100% (m/v), which has the consistency of a slightly thick liquid, similar to a nectar. In adult patients, we begin by testing this consistency with progressively increasing volumes, typically 5 cc, 10 cc and 15-20 cc / “big gulp”, the latter representing the volume the patient perceives to be a substantial bolus.19 To assess other consistencies, we dilute the barium contrast with water to achieve a thin liquid consistency and thicken it by mixing it with crumbs, prepared food or thickener to obtain “pudding” or “puree” consistencies. Solid boluses are generally evaluated by coating cookies in the barium suspension. Adaptations to this protocol are performed on a case-by-case basis, considering the patient’s symptoms, the overall clinical scenario and by using shorter protocols in paediatric patients. When deemed necessary, biphasic boluses, intermediate consistencies and/or continuous swallowing tasks are assessed. (Fig. 2)

VFSS requires a fluoroscope that is able to record cine clips and allows real-time analyses of the films. The temporal resolution of the equipment should ideally support a fluoroscopic acquisition rate of 30 frames per second to improve visualization of the rapid movements associated with swallowing and aspiration.20 To reduce radiation exposure and because temporal resolution is diagnostically more important than spatial resolution, fluoroscopy sequences are preferred to fluorography exposures.21 Furthermore, we typically adjust the temporal resolution during the examination based on the boluses which are being tested: thin liquids are assessed at 30 frames per second, nectar boluses at 15 frames per second and solid boluses at 3.75 frames per second. Radiation exposure time is the main factor influencing total radiation dose and fluoroscopy times should be kept to the bare minimum, ideally not exceeding 3 to 5 minutes. Overall, swallowing studies expose patients to a relatively low dose of radiation, with effective radiation doses ranging from 0,04 to 1 mSv.21,22

Lateral views are obtained for most of the examination and the field-of-view should include the oral and pharyngeal cavities, the posterior cervical spine, and the upper cervical oesophagus. Frontal views are limited to one or two boluses to evaluate pharyngeal symmetry, and it is often necessary to ask the patient to extend their neck slightly to improve visualization of the pharynx.23 Given that a considerable amount of oropharyngeal dysphagia is caused by referred oesophageal pathology, we usually perform a limited esophagogram in the antero-posterior and left posterior oblique positions to rule out other causes of dysphagia.5,11

Normal findings in VFSS

For accurate interpretation of VFSS, it is essential to recognize that certain morphological findings can be normal and may depend on the consistency of the boluses tested. Quantitative variables such as precise bolus transit times and displacement measurements of anatomic structures have been described elsewhere24, but we do not routinely apply them as we find them cumbersome and of limited diagnostic value.

Oral phase

Evaluation of the oral phase of deglutition requires a simultaneous clinical and radiological approach because radiographic films are limited in the assessment of the movement of food within the oral cavity. This is particularly important for the evaluation of the preparatory phase of deglutition.

Key events in the oral phase of swallowing are: 1) preparatory phase; 2) oral control of boluses; and 3) oral propulsive phase.

Preparatory phase:

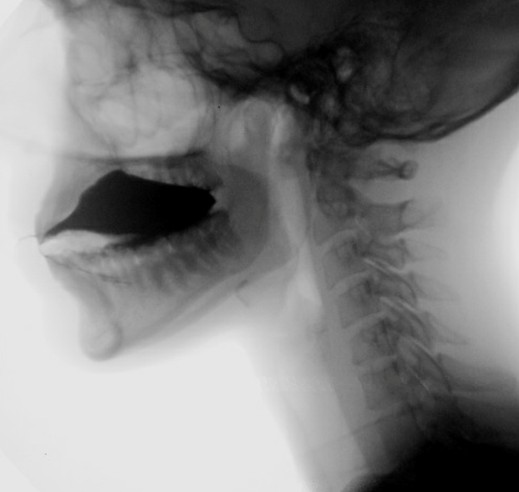

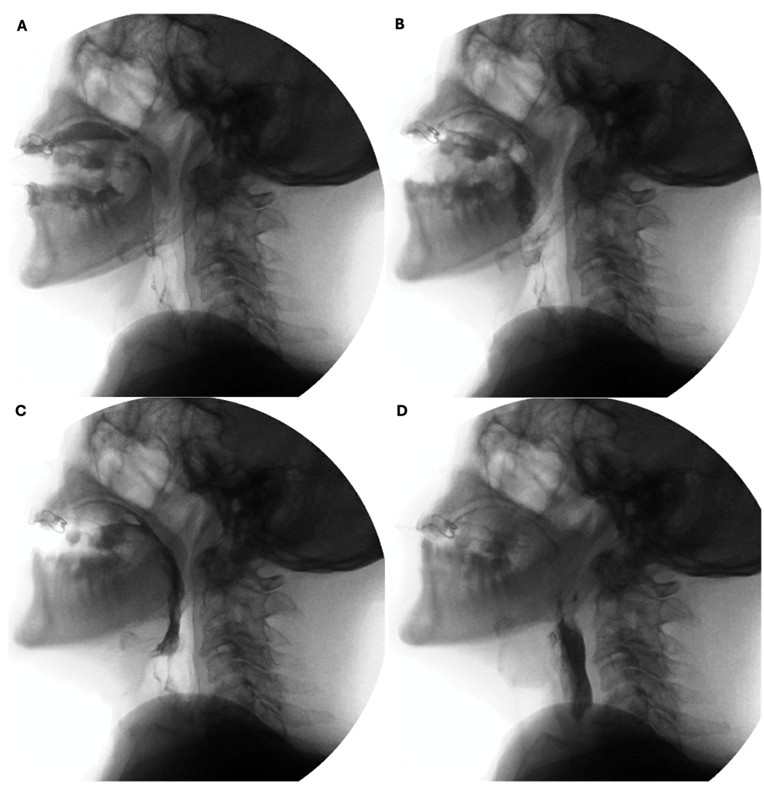

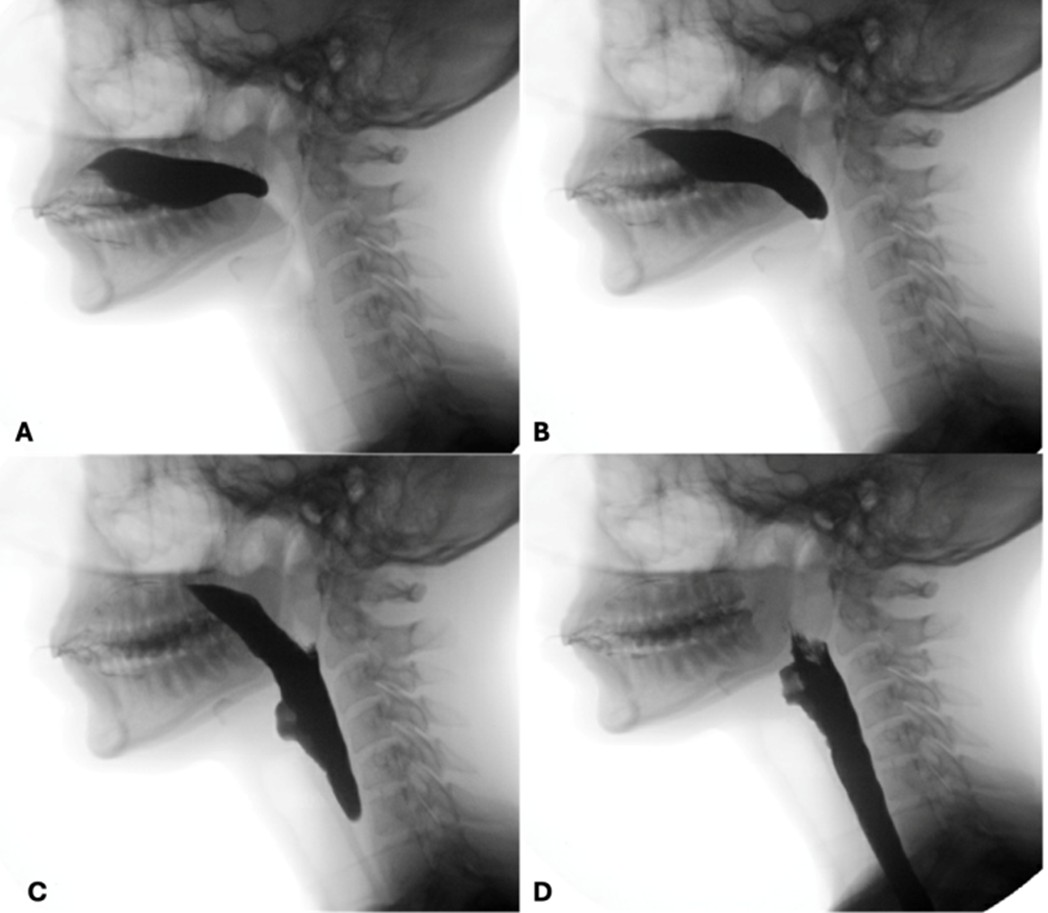

The preparatory phase of deglutition applies exclusively to the deglutition of solid food and boluses are prepared through a three-stage process that occurs simultaneously17: phase I transport - the tongue performs rotational movements to displace food posteriorly and laterally onto the occlusal surface of postcanine teeth; food processing - mastication and mixture of food with saliva alters the consistency of the boluses and prime it for swallowing; and phase II transport - processed food is pushed to the oropharynx, where it aggregates before being swallowed. By combining clinical and radiological evaluations, defects such as prolonged food processing time or reduced tongue movements can be identified. (Fig. 3)

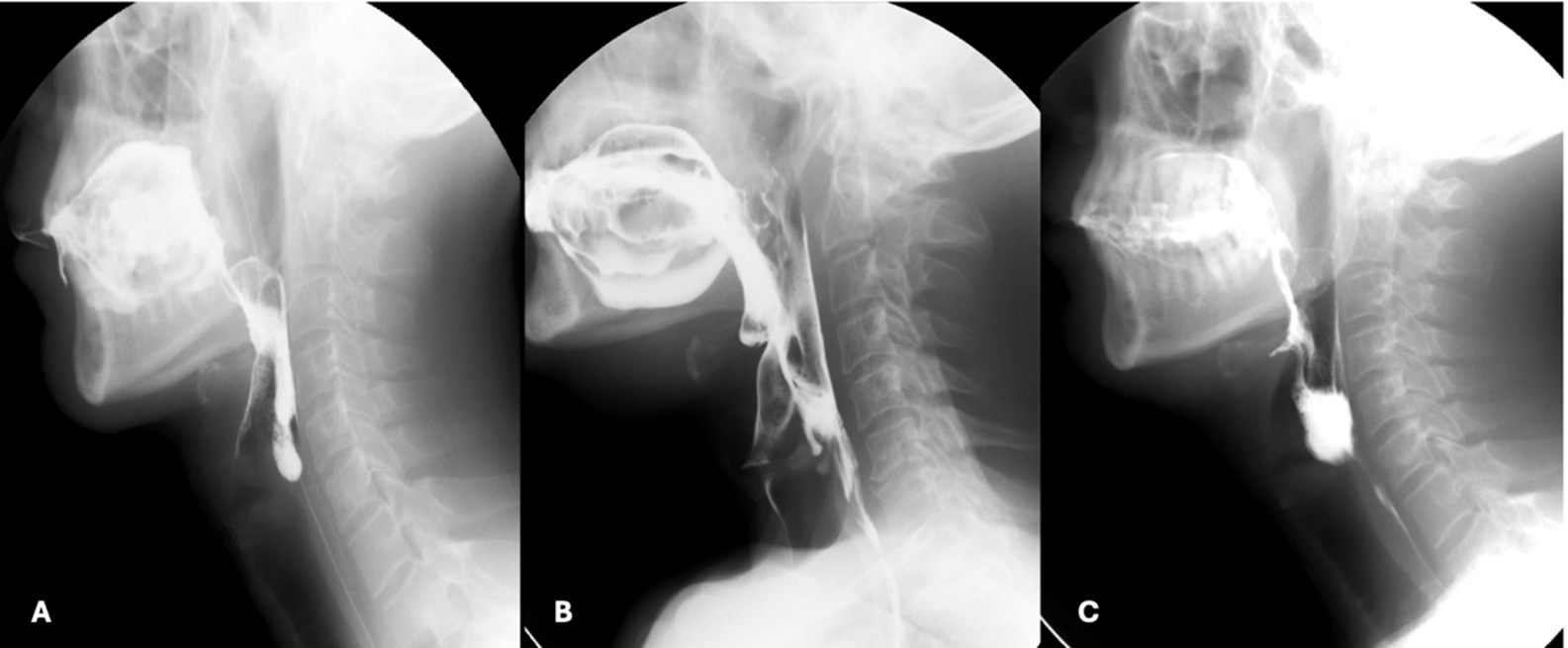

Figure 3: Preparatory phase of a solid bolus shows mastication (A) followed by phase II transport to the oropharynx (B and C) before swallowing (D)

Oral control of boluses

Before swallowing, patients should be able to voluntarily retain a bolus on the oral cavity without spill. This ability relies on the competence of the lips to prevent anterior escape, the velo-lingual valve to prevent posterior escape, and the tongue and cheek muscles to maintain the bolus on top of the tongue and prevent lateral escape to the floor of the mouth. (Fig. 4)

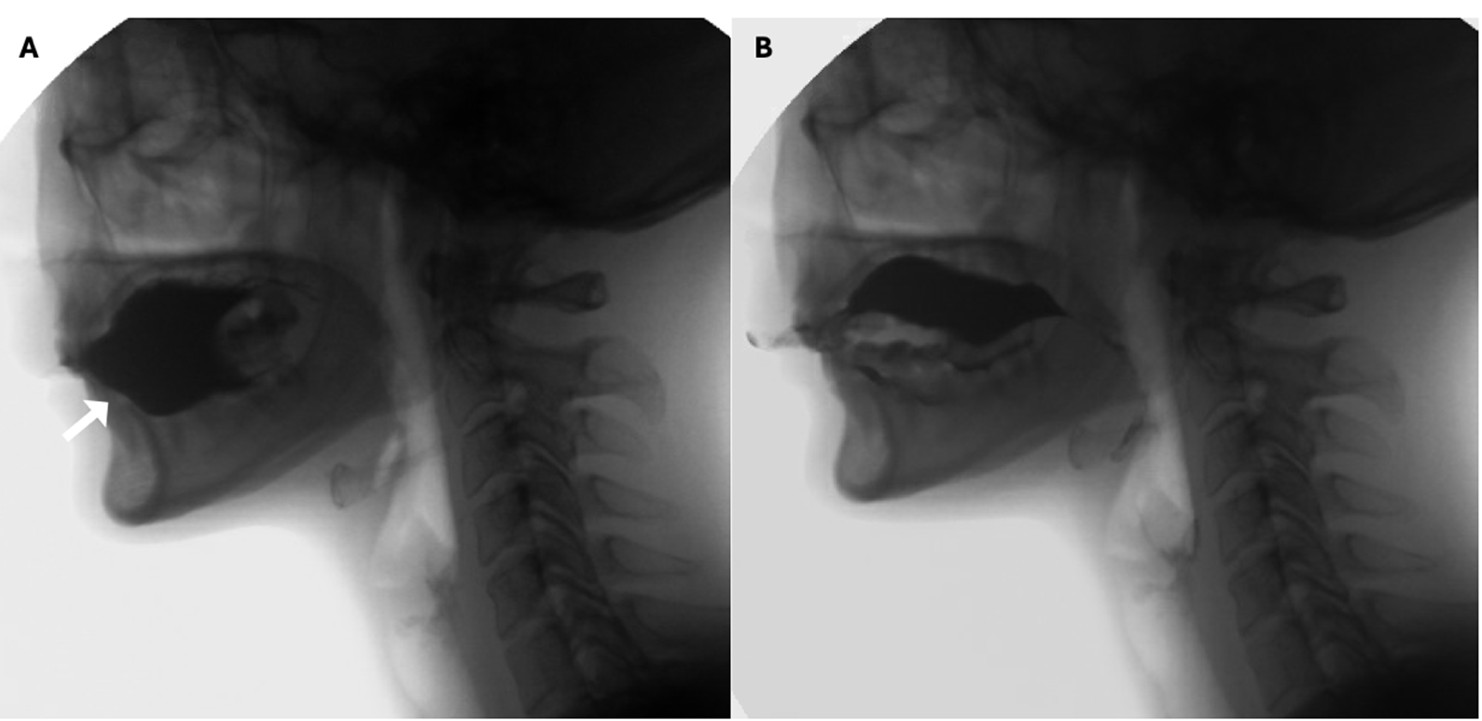

However, 5% of individuals may physiologically store boluses on the floor of their mouth instead of on the top of their tongues, a normal variant known as the dipping pattern of bolus hold. Unlike the more common tipping pattern, “dippers” use their tongue in a spoon-like motion to collect boluses from the floor of the mouth when transferring them to the pharynx. (Fig. 5) 25,26

Figure 5: Dipping pattern of bolus hold. Notice that before swallowing the contrast rests on the floor of the mouth (white arrow in A). In the oral propulsive phase, the tongue shows a spoon-like movement that scoops the entirety of the bolus (B)

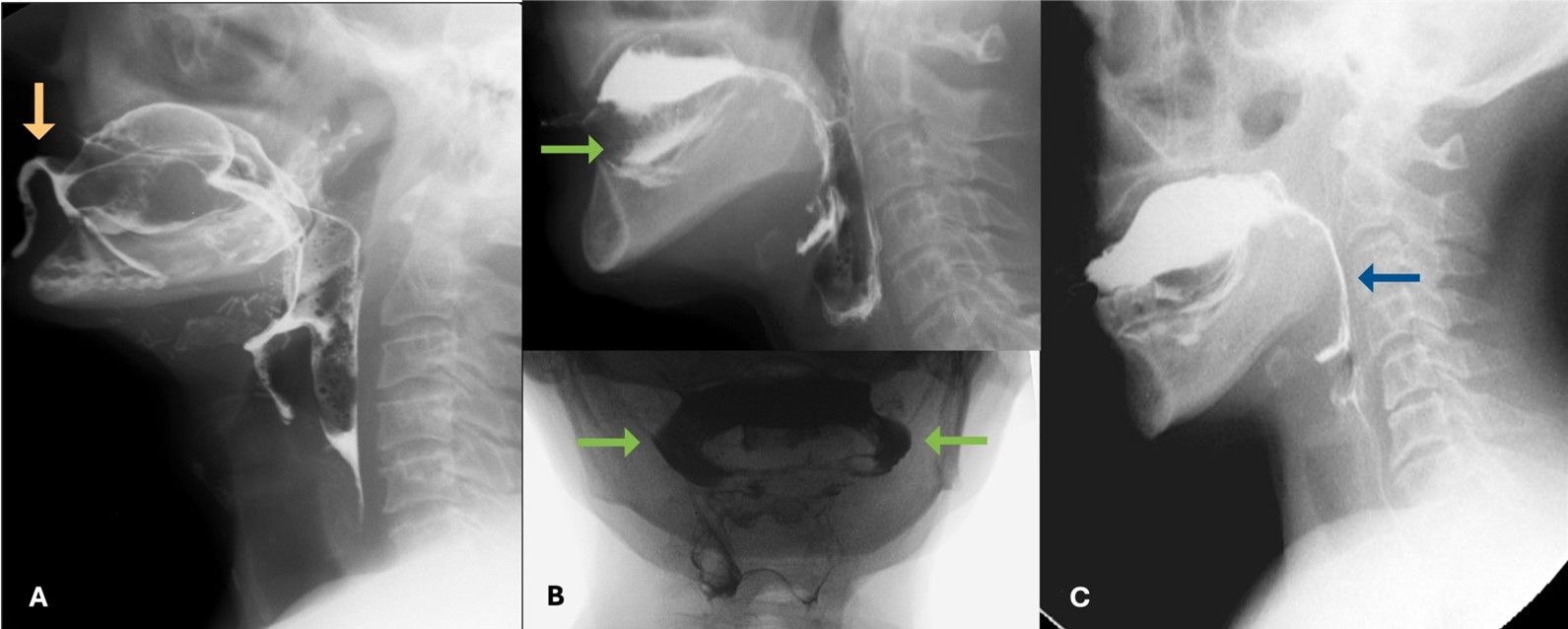

Defects in oral control of boluses are usually more apparent with liquid consistencies, especially thin liquids, as better muscular tonus is required for adequate management of this consistency. (Fig. 6)

Figure 6: Compromise of the oral control of boluses with anterior escape (orange arrow in A), lateral escape (green arrows in B) and posterior escape (blue arrow in C)

Oral propulsive phase

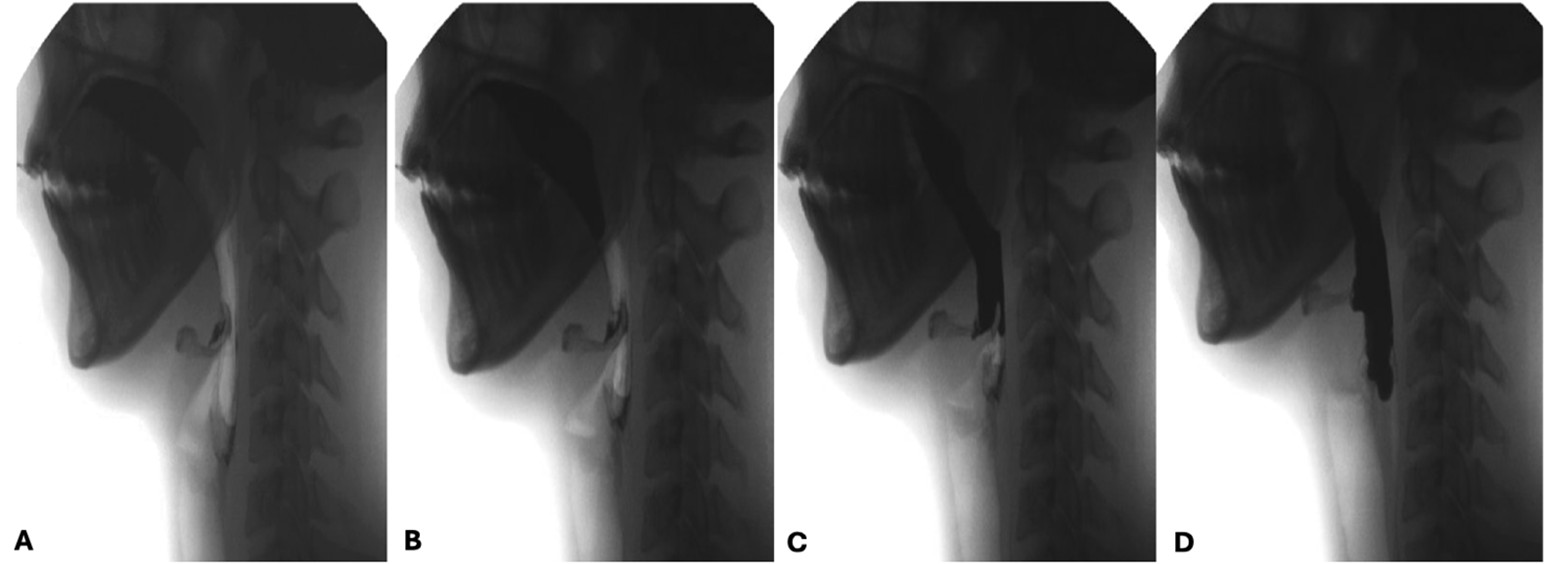

After the preparation of the boluses, voluntary transport to the pharynx occurs through coordinated movements: the tongue contracts, elevates anteriorly and depresses posteriorly, and the soft palate muscles relax, facilitating passage of the bolus through the fauces. This process usually lasts less than 1 second and the bolus is entirely propelled to the pharynx.

Bolus transport is most often impaired by reduced tongue strength, poor coordination of bolus movement and persistence of residue in the oral cavity, resulting in prolonged oral transit times. (Fig. 7)

Figure 7: Oral propulsive phase. Notice the tongue eversion and soft palate relaxation (A and B) with transfer of the bolus to the pharynx (C and D)

Pharyngeal phase

Clinical evaluation of the pharyngeal phase is limited and videofluoroscopy is a valuable non-invasive tool to study the function and coordination of the muscular structures involved in this phase.

Key events in the pharyngeal phase of swallowing include: 1) triggering of the swallow reflex; 2) airway protection; 3) nasopharyngeal closure; and 4) pharyngeal propulsion.

Triggering of the swallow reflex:

The triggering of the swallow reflex marks the beginning of the involuntary stage of deglutition and is radiologically defined by the brisk anterior-superior movement of the hyoid bone. Traditionally, this reflex has been thought to be invariably triggered when the boluses pass the radiological level of the angle of the mandible, but this depends on the consistency of the boluses being tested13,27. To standardize the assessment and avoid overcalling reflex delays, we evaluate the triggering of the reflex based on the passage of thin liquid boluses beyond the level of the mandibular angle. (Fig. 8)

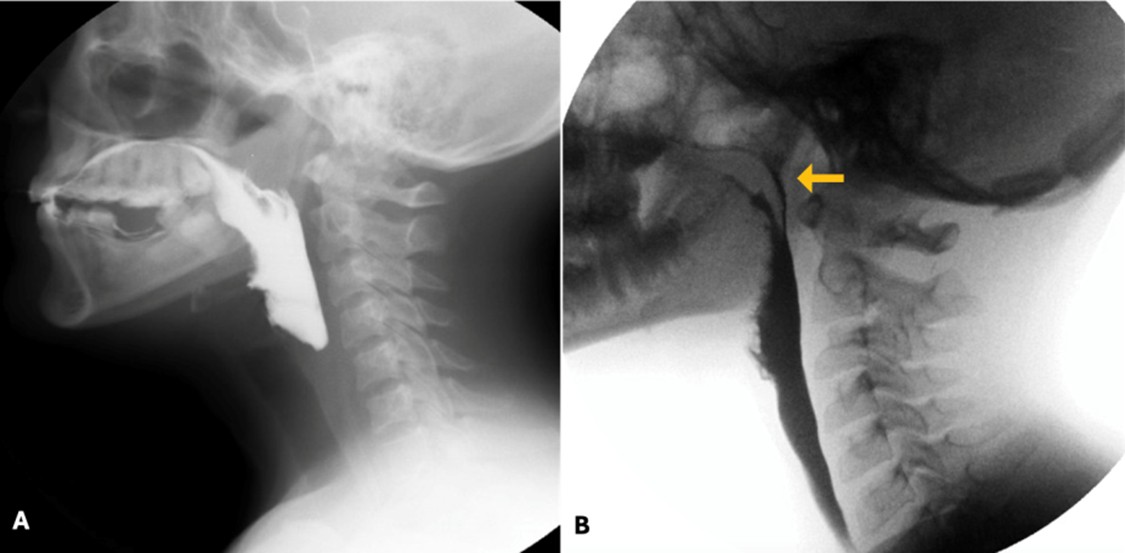

Figure 8: Oropharyngeal transport of a liquid bolus. When the contrast reaches the level of the angle of the mandible, the hyoid displays a brisk anterior-superior movement in (B) signalling the start of the swallow reflex

Delayed triggering of the swallow reflex may be caused by motor or sensory neuropathy and can be influenced by food consistency, bolus volume or voluntary muscle effort to push the bolus to the oropharynx. These findings should be documented to enhance the understanding of a patient’s dysphagia and help tailor potential treatment plans.

Airway protection:

During pharyngeal transit a coordinated muscular response is initiated to ensure airway closure and prevent aspiration of food. This is primarily achieved through hyolaryngeal elevation, contraction of the aryepiglottic folds and retroflexion of the epiglottis, which abuts and closes the opening to the laryngeal vestibule.

Adequate elevation of the hyoid-laryngeal complex is a key factor in achieving effective glottic closure and this can be evaluated by assessing the maximum vertical displacement of the hyoid. Under normal conditions the hyoid should reach the level of the ramus of the mandible, but this has been shown to be variable with bolus size and is more reliably seen with the deglutition of big boluses.28

Epiglottic movement can be difficult to evaluate on videofluoroscopy as its assessment relies on indirect images from the movement of contrast through the pharynx, but complete laryngeal closure may be inferred when no air or contrast accesses the laryngeal vestibule. (Fig. 9)

Figure 9: Under normal circumstances, the laryngeal inlet closes completely and no contrast is seen on the laryngeal vestibule. Notice the adequate elevation of the hyoid bone which reaches the level of the ramus of the mandible.

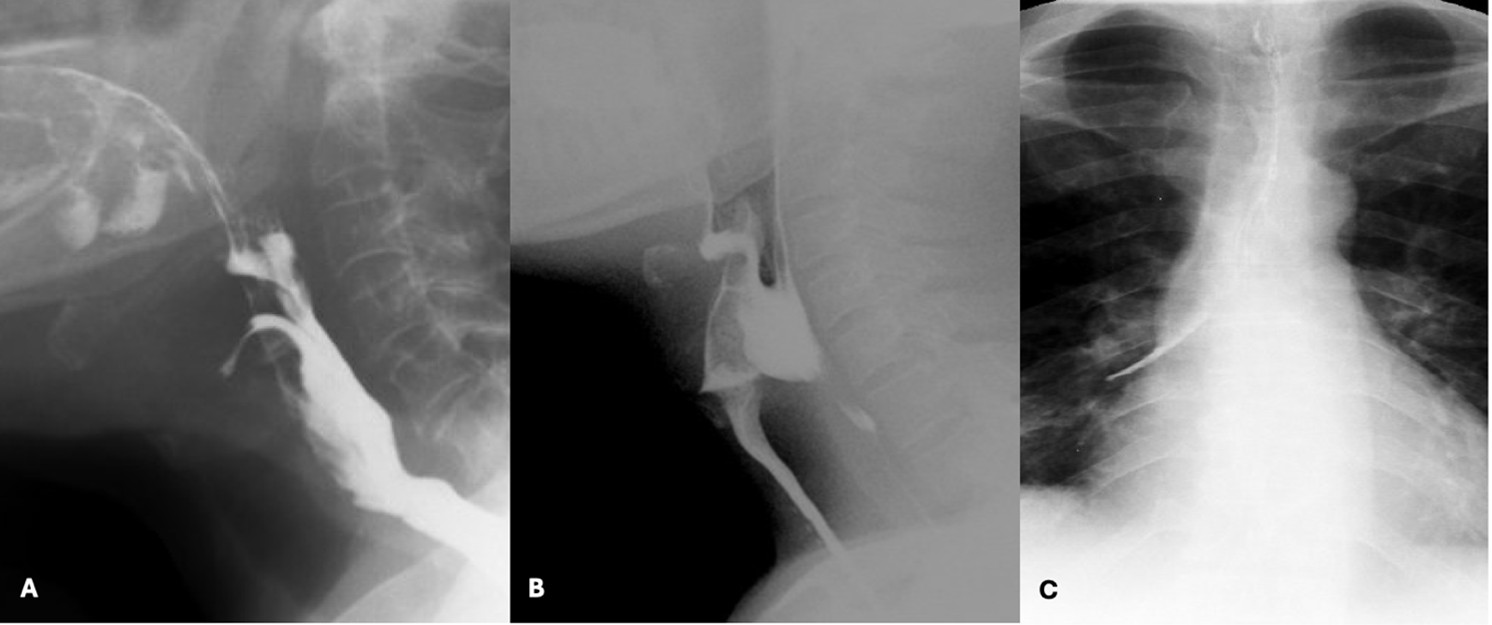

When food enters the airway, different degrees of severity can be observed: the term penetration is used when boluses enter the larynx but remain above the vocal folds, while aspiration is used when they pass below this level. Usually, we grade the subjective amount of contrast that accesses the airway, state whether a cough response was triggered (i.e. if silent aspiration is present or not) and if there is effective clearance of contrast from the airway. A more objective assessment can also be employed by using the Penetration-Aspiration Scale developed by Rosenbek et al.29 (Fig. 10)

Figure 10: Spectrum of airway protection impairment severity - penetration (A), aspiration (B) and aspiration that reaches the right main bronchus (C)

Penetration and aspiration can be classified according to the timing of their occurrence, which helps to identify the underlying causal mechanism. When there is incomplete closure of the larynx or delayed triggering of the swallow reflex, contrast enters the airway during the pharyngeal phase of deglutition. Aspiration can also occur before the pharyngeal phase of deglutition, typically in the setting of posterior escape from the oral cavity or poor coordination in oropharyngeal bolus transport. On the other hand, aspiration can also occur after the pharyngeal phase of deglutition when there are persistent pharyngeal residues that can spill into the airway when the larynx opens - this occurs when pharyngeal clearance is hindered by insufficient contraction of pharyngeal muscles, incomplete opening of the upper oesophageal sphincter or presence of obstructive masses. (Fig. 11)

Figure 11: Range of underlying causes for compromised airway protection. (A) Posterior bolus escape from the oral cavity resulting in laryngeal penetration before the pharyngeal phase of deglutition; (B) Aspiration of contrast during the pharyngeal phase of deglutition due to delayed triggering of the swallow reflex; (C) Persistent pharyngeal residues that resulted in the aspiration seen in the panel B of figure 10

It is important to note that minor episodes of penetration into the laryngeal vestibule, defined as asymptomatic, transient, and with complete clearance may occur in healthy individuals throughout a meal.

Nasopharyngeal closure

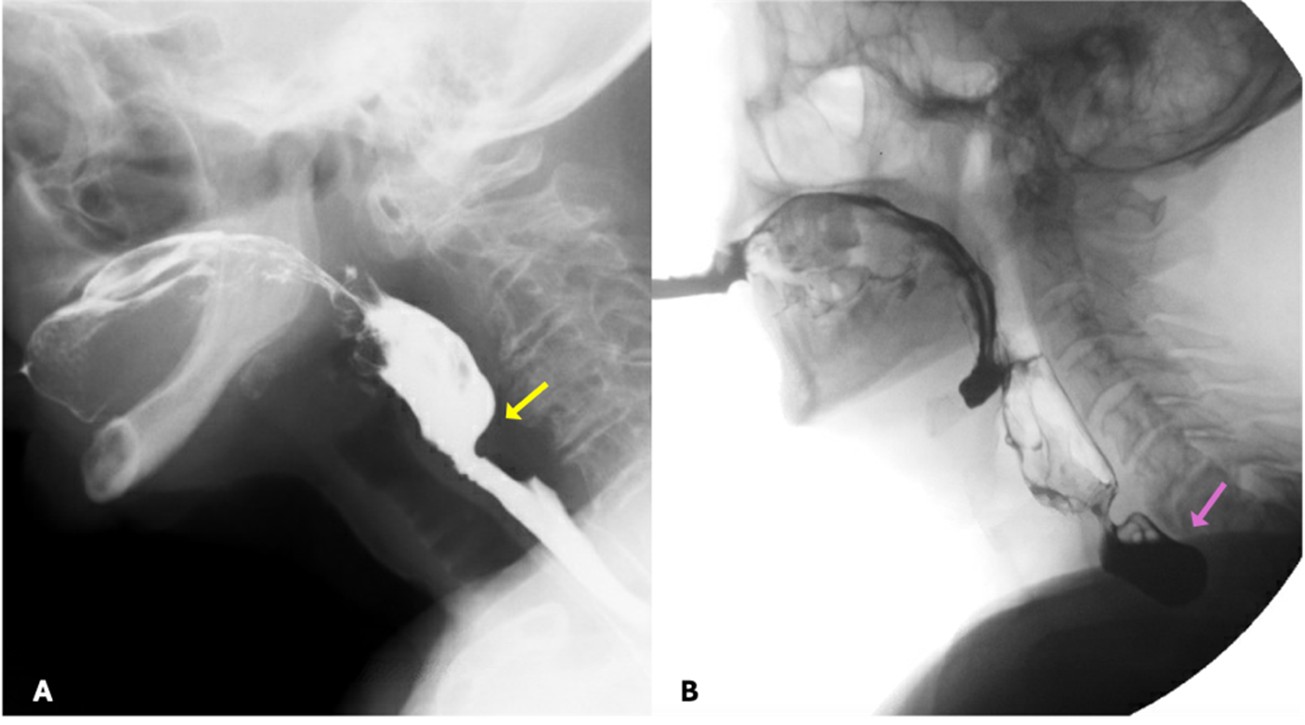

Under normal conditions, during the passage of food through the pharynx, the nasopharynx is closed by the velopharyngeal valve. When this mechanism is defective, food may enter the nasopharynx and/or the nasal cavity, typically due to weakness of the muscles of the soft palate. (Fig. 12)

Figure 12: Normal nasopharyngeal sealing mechanism (A) and penetration of contrast into the nasopharynx (orange arrow in B)

Pharyngeal propulsion

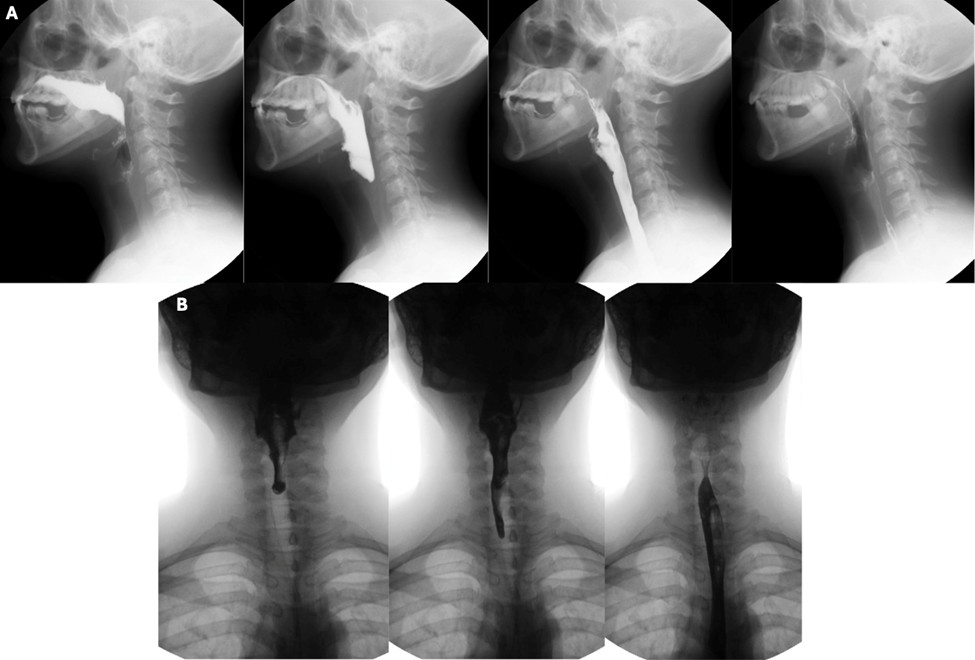

Pharyngeal peristalsis is achieved through sequential contraction of the pharyngeal constrictors, which propel the boluses forward through the upper oesophageal sphincter and into the oesophagus. Normal pharyngeal transit times, defined as the time it takes for the bolus to move from the oropharynx to the oesophagus, are usually under one second. (Fig. 13)

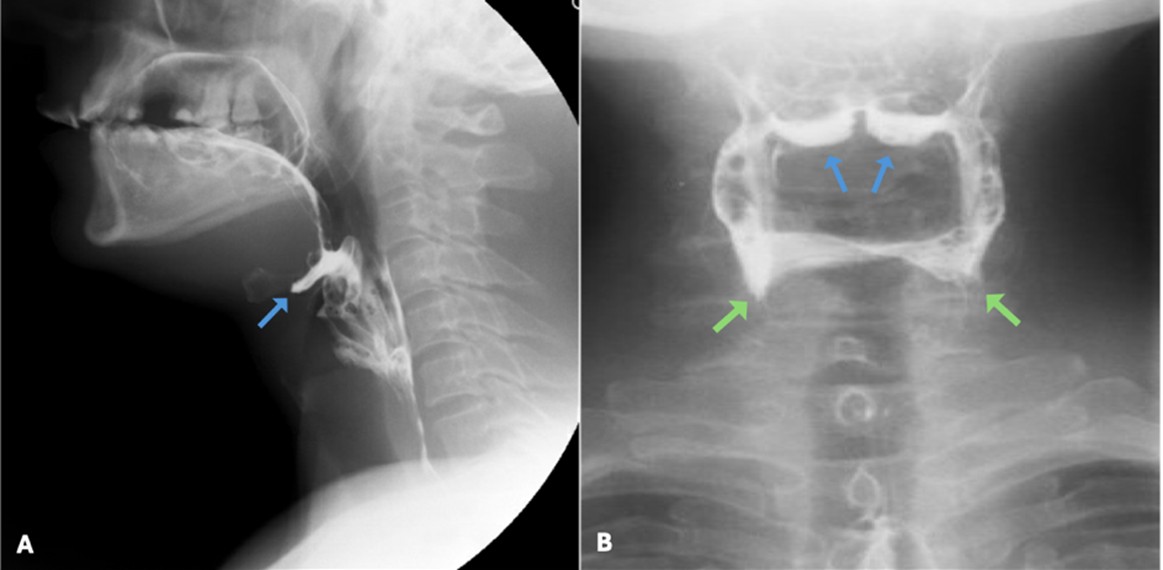

Impaired pharyngeal muscular contraction results in increased pharyngeal transit times and persistence of pharyngeal residues in the piriform sinuses, posterior hypopharyngeal wall or above the upper oesophageal sphincter. Anterior-posterior views should be evaluated for asymmetric contraction of the pharyngeal muscles or asymmetric retention of contrast, findings which may suggest vagus nerve paresis or the presence of a mass, respectively. (Fig. 14)

Figure 14: Pharyngeal residues in the vallecula (blue arrows) and piriform sinuses (green arrows) in lateral (A) and anterior-posterior (B) views

Upper oesophageal sphincter opening

The opening of the upper oesophageal sphincter depends on cricopharyngeal muscle relaxation, elevation of the hypopharynx and pharyngeal luminal pressures. Under normal conditions the upper oesophageal sphincter opens completely, allowing unobstructed transit of the boluses.

Upper oesophageal sphincter dysfunction can be attributed to extrinsic causes when the pharyngeal muscles do not generate enough pressures to propel the boluses through the upper oesophageal sphincter or to an intrinsic defect in the relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscle. The latter usually presents as a transient or persistent cricopharyngeal bar that restricts the passage of contrast to the oesophagus and can be associated with a Zenker’s diverticulum. (Fig. 15)