Case Presentation

A 32-year-old male patient, originally from Brazil and living in Portugal for the past year, sought emergency medical observation for a 1-month history of respiratory symptoms, including shortness of breath, fatigue and occasional productive cough. The patient also reported significant weight loss (10 kg in 2 months). He denied having fever and night sweats. He had a history of chronic Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1) infection, currently treated with antiretroviral therapy (HIV viral load <20 copies/mL, CD4+T 638 cells/mm3). Physical examination was unremarkable.

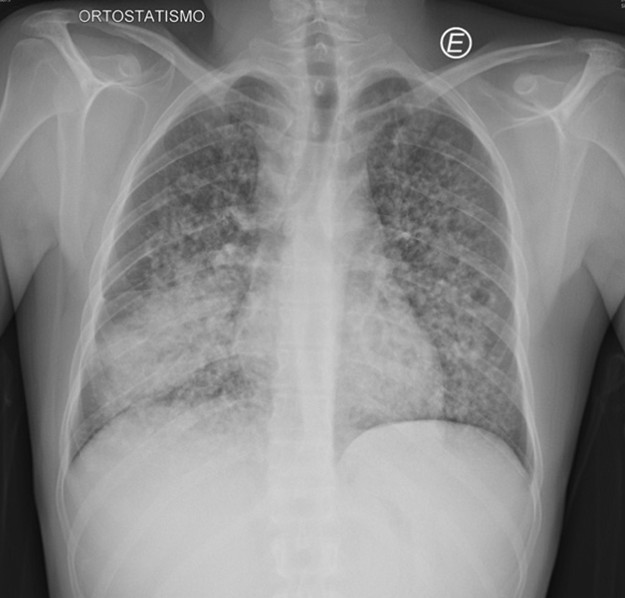

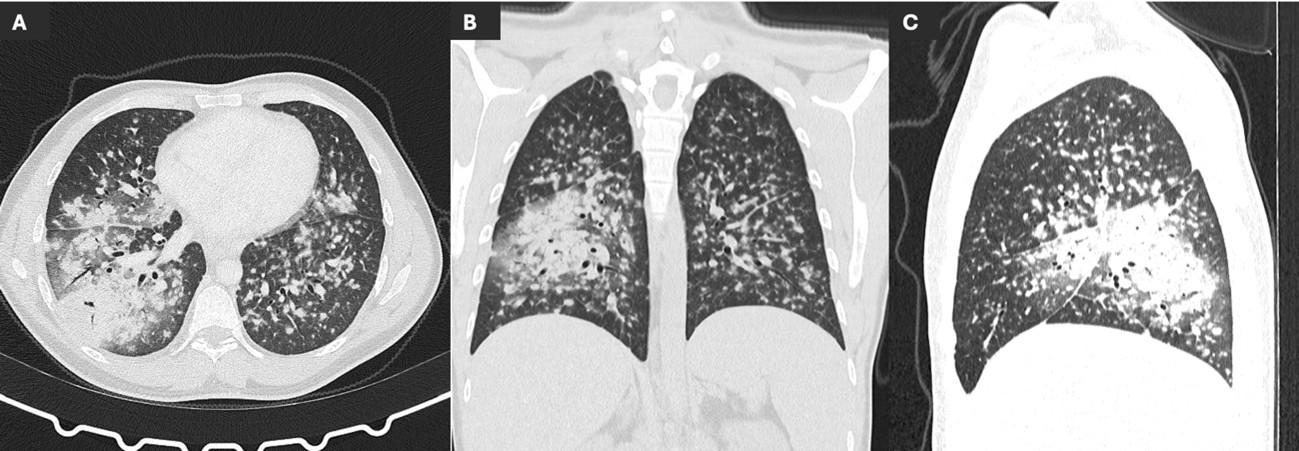

A chest radiograph (Figure 1) and a thoracic computed tomography (CT) were performed, revealing multiple bilateral solid and subsolid nodules, ill-defined and with varying sizes (not exceeding 1 cm), with a tendency to confluence and mostly with a peribroncovascular pattern of distribution, although some juxta-pleural nodules were seen (Figure 2). Additionally, a consolidation on the middle and right lower lobe with air-bronchogram was identified (Figure 2). Multiple enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes were also present, some with central hypodensity suggestive of necrosis (Figure 3). Pleural effusion was excluded.

A bronchofibroscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage were later carried out and a fungus was isolated on culture, identified as Histoplasma capsulatum.

Figure 1: Chest radiograph showing an airspace consolidation with air bronchogram in the right lower hemithorax, associated with multiple and bilateral nodules.

Figure 2: Axial (A), coronal (B) and sagittal (C) non-enhanced CT scan showing multiple nodules in both lungs, solid and subsolid, with varying sizes and mostly with a peribroncovascular pattern of distribution, associated with a middle and right lower lobe consolidation.

Discussion

Histoplasmosis is an infection with worldwide distribution, caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that exists as a zoonosis within bats or that can be found in places where the soil is contaminated with droppings from birds.1 Humans are usually exposed through inhalation of dust or aerosols from farming, caves or construction sites.

After exposure, most cases are asymptomatic or self-limited,1 however, symptomatic infection may occur, especially in those exposed to a large inoculum of organisms or a virulent H. capsulatum strain and those with a suppressed immune system. It usually presents as an acute viral-like illness consisting of cough, fever, dyspnea, headache and myalgias. Chronic or disseminated forms of histoplasmosis are rare and occur mostly in immunocompromised patients, clinically manifesting with low-grade fever, fatigue and weight-loss.

The diagnosis of histoplasmosis is usually ascertained by direct observation or isolation of the pathogen (culture), but antigen detection has provided a rapid, noninvasive, and highly sensitive diagnostic method and is a useful marker of treatment response.2

The imaging findings of pulmonary histoplasmosis are varied and nonspecific.

In its acute stage, chest radiographs are typically normal, but they can demonstrate lobar or segmental consolidation or multiple air-space opacities,3 as in the case we presented. Imaging might also show solitary or multiple pulmonary nodules that can vary in size and have smooth or irregular contours, with or without a ground-glass halo.

Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can lead to hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement, that may exert a mass effect on adjacent structures. Pleural effusions are uncommon.3

As the disease progresses, the consolidation diminishes and a residual nodule is formed. In some cases, the nodule may continue to enlarge, due to formation of marginal fibrosis, being called a histoplasmoma. It eventually calcifies and remains as a calcified granuloma, indicating prior exposure. Infected lymph nodes may also calcify over time.

Disseminated histoplasmosis is a rare form of infection with H. capsulatum that mainly occurs in immunocompromised patients1. Initial chest radiographs are also often normal, but when they are not, they usually present with diffuse nodules, typically smaller than 3 mm and with a miliary pattern of distribution, mimicking miliary tuberculosis or hematogenous metastases. Lymphadenopathy and pleural effusion are generally absent.

Regarding chronic infection, the disease usually manifests as an upper lobe consolidation, that can evolve to focal scar or cavitation. Similarly to tuberculosis, these cavities typically involve the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and may develop wall thickening, an air-fluid level and adjacent pleural thickening. In contrast to acute infection, adenopathies are infrequent.

Broncholithiasis is a late and uncommon complication of pulmonary histoplasmosis4 that forms when a calcified peribronchial nodule or calcified lymph node erodes through or involves an airway wall. On CT scan it presents as an endobronchial calcification that can result in postobstructive atelectasis, air trapping, hemoptysis and fistula formation.

Fibrosing mediastinitis is another rare but severe consequence of histoplasmosis, with high morbidity and mortality. It corresponds to excessive proliferation of fibrotic tissue around the mediastinal lymph nodes, that can lead to incarceration of mediastinal structures,4 mostly resulting in obstruction of the superior vena cava. On CT examination it manifests as a soft-tissue mass and infiltration within the mediastinum and hilum.

On imaging examinations, histoplasmosis can be indistinguishable from other infectious diseases, inflammatory conditions and neoplasms.

In the acute setting of histoplasmosis, the main differential diagnosis is usually community-acquired pneumonia4 and most patients with histoplasmosis are undiagnosed. Those who present with a solitary nodule are often misdiagnosed with primary lung malignancy, but the development of calcification might prevent further clinical workup.

Disseminated histoplasmosis with miliary nodules cannot be differentiated from other infectious causes of miliary disease such as tuberculosis. It can also mimic metastatic disease, although these usually vary in size and exceed 3 mm.4

Chronic infection might also be difficult to differentiate from tuberculosis and malignancy, and usually differentiation requires bronchofibroscopy or biopsy.

Effective treatment for histoplasmosis typically involves antifungal medications such as itraconazole, while severe or disseminated cases may require hospitalization and intravenous antifungals like amphotericin B.5

This case demonstrates not only the challenge that the diagnosis of histoplasmosis poses to radiologists but also the importance of learning its radiologic manifestations and of considering histoplasmosis in patients residing in or coming from an endemic area.