1. Introduction

In general, the term "creativity" is commonly used in our language without a single, certain, or universally accepted meaning, which can lead to confusion. The approach of creativity being something not fully understood or used interchangeably is not useful in the long term if we wish to work with and encourage creative practices. Instead, we must take ownership of our creativity as it adds richness and complexity to our way of life (Jennings, 2011).

The connection between Fashion (capital F, referring to the Fashion system, especially high-end design) and creativity seems obvious. Fashion, as a field of constant newness and considered part of the arts within academia, often presents the idea of creativity in this field as special and unique to those who engage with it. Fashion designers in high-end brands are frequently regarded as geniuses for the creativity they bring to their creations. This is not specific to the field of Fashion, as many art forms have historically appraised successful artists as geniuses or as possessing superior creativity. Growing up watching Project Runway or more recent shows like Making the Cut and Next in Fashion, it is possible to observe designers battling and struggling as they compete to be recognised as the and most talented and creative designer and therefore the "next in Fashion" decided by judges who hold status within the Fashion system themselves - as models, designers, stylists or fashion icons. This connection of creativity and Fashion is focused on geniuses, but there is also creativity connected to our everyday fashion practices. All human beings utilize creativity in various forms and are creative, not only in the arts. We all use fashion daily, as we dress for the day ahead and make choices on what to wear to best reflect our identity, feel comfortable, or convey confidence. Is this not an example of creativity in everyday life?

The Fashion system provides us with trends and what is "in style", but at the same time, each person makes their own styling choices and puts together outfits that require some amount of creativity. Often, truly reflecting one's identity requires considerable creativity and introspection. Even though we rely on the Fashion system to "tell" us what is right and wrong, maybe because we feel we are not creative enough on our own. Being creative with fashion choices can also be scary or even dangerous if you step outside what is considered the norm. This, in turn, may limit our creativity when choosing an outfit, causing us to hesitate with thoughts like "what will people think if I wear this, or that?" and so on. Creativity Takes Courage (Smit & van der Hulst, 2018) is the title of one of the books I use as a reference in this paper; another one is entitled Creative Living Beyond Fear (Gilbert, 2015). Being creative with our style takes courage, but why is there this fear and need for courage? What contextual conditions enable and limit our creative freedom in our everyday fashion practices?

2. Theories on Creativity

To understand what creativity is and how it relates to fashion, I researched various theories on the nature of creativity and its underlying mechanisms. The term "creativity" is challenging to define and is widely used in different contexts across multiple fields. Some might compare it to "love", suggesting that it is something not meant to be fully understood but experienced (Jennings, 2011). This approach is not useful, as it does not encourage us to take ownership of our creativity, which is essential since creativity adds to the richness and complexity of life.

Creativity is about connections and interactions, innovation, and originality, which, when we engage with it, gives us the ability to live life to the fullest (Jennings, 2011). Creativity is not just practical, as it helps us solve problems and invent; it is also a form of self-expression (Boon, 2014), as evident in fashion, when we use clothes to shape our identity. Creativity is what truly makes fashion, rather than simply wearing clothes for practical reasons, such as keeping warm. Being creative with our fashion choices enables us to reveal our inner selves to our surroundings, as the symbols inherent in our outfits allow people to decode and understand us. Being creative, let alone expressing creative freedom in fashion, is a challenging task. As mentioned in the introduction, there has been a tendency to attribute creativity to "geniuses" in both everyday life and academia (Glăveanu, 2014). Many examples of this could be mentioned, but as Judkins (2016) explains:

the cult of the creative genius appeared with art's first superstar, Michelangelo. In 1550, his biographer and PR guru, Vasari, promoted the idea of the "Divine Michelangelo". His talent was a gift from God, Vasari said, and claimed that God bestowed such ability only on the privileged few, the chosen ones. It fostered an elite and disempowering attitude to creativity. (p. 12)

In many fields of research, the idea that an elite possesses creative skills is being challenged today, as we try to understand creativity in different ways. Our entire system is built on promoting this idea as well as the notion that creativity thrives in certain fields, often in the arts. However, creativity is not reserved for the creative elite, the acclaimed, or the famous. It is constantly used in everyday life and is regarded as a normally distributed trait found in everyone to varying degrees (Jennings, 2011), making creativity omnipresent (Boon, 2014).

Being creative is present when an artist paints, a scientist researches, and when you pick out which shoes to wear with your jeans, there is no single best way to be creative (Jennings, 2011). This "box" that has otherwise been constructed around the genius has strong walls, both material and symbolic, and limits creative production (Glăveanu, 2014). There is a difference between being creative on a personal level and on a historical level.

On a personal level, we are all creative to some extent ( ... ). Though these actions use the brain in a creative manner, they will never enter the public arena ( ... ). So, to be historically creative, you need to at least have the intention to contribute something to a creative domain. (Boon, 2014, p. 27)

As we all inherently possess creativity, acquiring it is not the challenge; instead, it is about enabling the full potential of this creativity, both in historical and personal creative practices (Jennings, 2011). To access our creative potential, we need to live a life driven more by curiosity than fear (Gilbert, 2015) because creativity is essential for finding solutions to our daily problems and for addressing societal issues (Smit & van der Hulst, 2018).

3. Distributed Creativity

One aspect of this involves challenging the "genius" approach to creativity, where the fear arises that we are not capable of doing something or being creative because it is perceived as a trait reserved for a select few. This perception must be addressed through changes in practice and education to foster and enrich the potential for nurturing creativity (Glăveanu & Kaufman, 2022).

Another obstacle is external judgment (Boon, 2014), along with social factors, which have often been examined in isolation when investigating creativity and psychology, focusing separately on the individual, the context, and the social, rather than adopting a dynamic conception (Glăveanu, 2014). A theory that is useful for challenging these issues and has highly influenced the method used in this paper is the theory and methodology of distributed creativity by Vlad Petre Glăveanu (2014). This theory challenges the traditional approach to investigating creativity "inside the box", that is, inside the mind of the individual, by proposing a distributed model of creativity, developed through the study of a case in folk arts. Expanding on an existing paradigm of psychology, the we-paradigm which means "away from univariate, positivistic research paradigms to more complex, constructivist, systems-oriented research models ( ... ) based on the general idea that creativity takes place within, is constituted and influenced by, and has consequences for, a social context" (Glăveanu, 2014).

Glăveanu (2014) points not only to social relations (conceptualized as the Weparadigm) but also to interaction with artefacts and the development of creative expression over time. This method stands in clear contrast to the I- or Heparadigm, which focused on genius, non-distributed creation, or the idea that creative processes were bound to one single "centre" - the individual mind. The distributed approach, combined with the cultural psychology of creativity, extends into the social and material world, conceptualizing creative action. This means that

what a cultural psychological account of distributed creativity ultimately aims to do is "seek to recover the power inherent in the term [creativity] for bringing the elevated and the mundane into conjunction, and for illuminating how exceptional and the ordinary feed off each other". (Glăveanu, 2014, p. 85)

Creative expression is possible only from within a society and culture, viewing creativity not as a "thing" but as action in and on the world (Glăveanu, 2014). This means recognizing the self as an agent within an ever-changing world, wherein we can attempt to identify the conditions that enable and limit this individual's creativity in their given context. An important point is that, even as this method focuses on the context, distributed creativity is not about the person, but rather about analyzing the person within a context. Within the framework of distributed creativity, five distinct elements are presented, with a focus on the differences within sociality, materiality, and temporality that creativity acts on.

Glăveanu (2014) writes that advancing theory and method in the psychology of creativity involves focusing on what people actually do. This focus on the context and what people actually do when they are being creative in dressing their body is the basis of the method presented in this paper, as well as its emphasis on the emotional element by combining body and mind. Combinig not only the mind's creativity, but also the embodied practice of dressing, which is influenced by the present context, as Joanne Entwistle (2015) writes in The Fashioned Body: "understanding dress in everyday life requires looking not only at how individuals turn to their bodies but how dress operates between individuals as an inter-subjective experience as well as a subjective one" (p. 35). These theories on creativity, everyday fashion practices, and the fashioned body all influenced the method.

Creative practices and thinking can be applied to any field or project, but they are often more visible to people and adapt more easily to analysis in what is commonly known as "creative fields" such as the arts. Craftsmanship is frequently associated with creativity. Arts such as painting, jewelry making, knitting, and crafting in general have, and will likely continue to be perceived as more creative pursuits than, for example, accounting. This paper challenges the elitist view on creativity and its value in analysis by examining a common creative practice in which all humans in civilized society engage: getting dressed.

4. Methods for Inspiration to Enquiry

To gather empirical data for the paper, which draws on the presented perspectives of creativity, several methodologies were combined to develop a qualitative tool, called the "Outfit of the Day Logbook", designed to collect insights into the everyday human experience with fashion. The name was derived from a popular trend, originating on the social media platform Instagram, where using "OOTD" as a hashtag was and still is, to some extent, a way to present the outfits that people had creatively put together. In the same spirit of sharing and cataloguing the daily outfits, the research required respondents to record what they wore and provide commentary based on specific questions, while also allowing them to journal freely in their own style (Gaver et al., 1999).

The method itself could be further refined by more extensively incorporating cultural probe theory and methodology (Gaver et al., 1999), embracing openness and playfulness in the exploration of creativity through the logbook. In the logbook itself, there are some similarities to the cultural probe's methodology, such as the associative task of keeping a logbook, writing thoughts down like a diary, and taking pictures. However, it could be further developed into a comprehensive tool to investigate the contextual conditions of creativity. Some respondents used the logbook more openly than scripted, akin to a probe task, which in turn yielded interesting results and sparked the idea of combining the logbook method with the cultural probe methodology.

Primarily, the inspiration was wardrobe studies, as this method focuses on gathering data through investigations into the belongings in people's wardrobes using different approaches. Upon reviewing examples of other case studies that employ this method, inspiration is drawn from three specific approaches, which will be briefly presented here. However, readers are encouraged to consult the original material for a more comprehensive understanding if they wish to apply these methods (Fletcher & Klepp, 2017). The basis for the description of outfits was inspired by method 16 (Fletcher & Klepp, 2017).

Method 16 includes a wardrobe audit worksheet that asks respondents to record the garment type, brand, type of fiber, fabric, color, pattern, details, cut, age, and damage, which are many of the descriptive features used as examples for respondents to build their outfit descriptions in the logbook. The voluntary providing of a photo of the outfit was inspired by method 20 (Fletcher & Klepp, 2017), a "daily catalogue" where they took a picture of themselves every day so they could look back on it. Method 11 (Fletcher & Klepp, 2017) involves interviews, specifically those in which participants rate and compare chosen objects. This inspired some of the examples given for the emotional description, which was vital to the research, such as their feelings towards the objects, what they like and dislike, and so on. Interestingly, one of the students who was an early respondent used the logbook as a rating system, assigning a rating from 1 to 10 to their outfits. This is also what is used in Method 11 and might be a useful addition to the logbook method, depending on the research questions one wishes to investigate. Other than that, the emotional description part, which focuses on both internal and external experiences while wearing their outfits, was developed specifically for the logbook and, in that sense, is an extension of the wardrobe method, inspired by the distributed creativity theory.

As wardrobe studies primarily focus on what is in the wardrobe itself, the focus of this paper, along with the logbook, was on the creative practices behind the clothing choices made by the respondents and the experiences they had while interacting with the world and their context. This is somewhat mentioned in method 20, where the photos were accompanied by notes on their emotions, physicality, and daily interactions. Whereas this method focused on the contents of the wardrobe and the visual, the purpose of the logbook is to analyze creativity in everyday fashion practice, focusing on the emotional, embodied, and creative experience of the respondents (Entwistle, 2015).

5. Introduction to Research

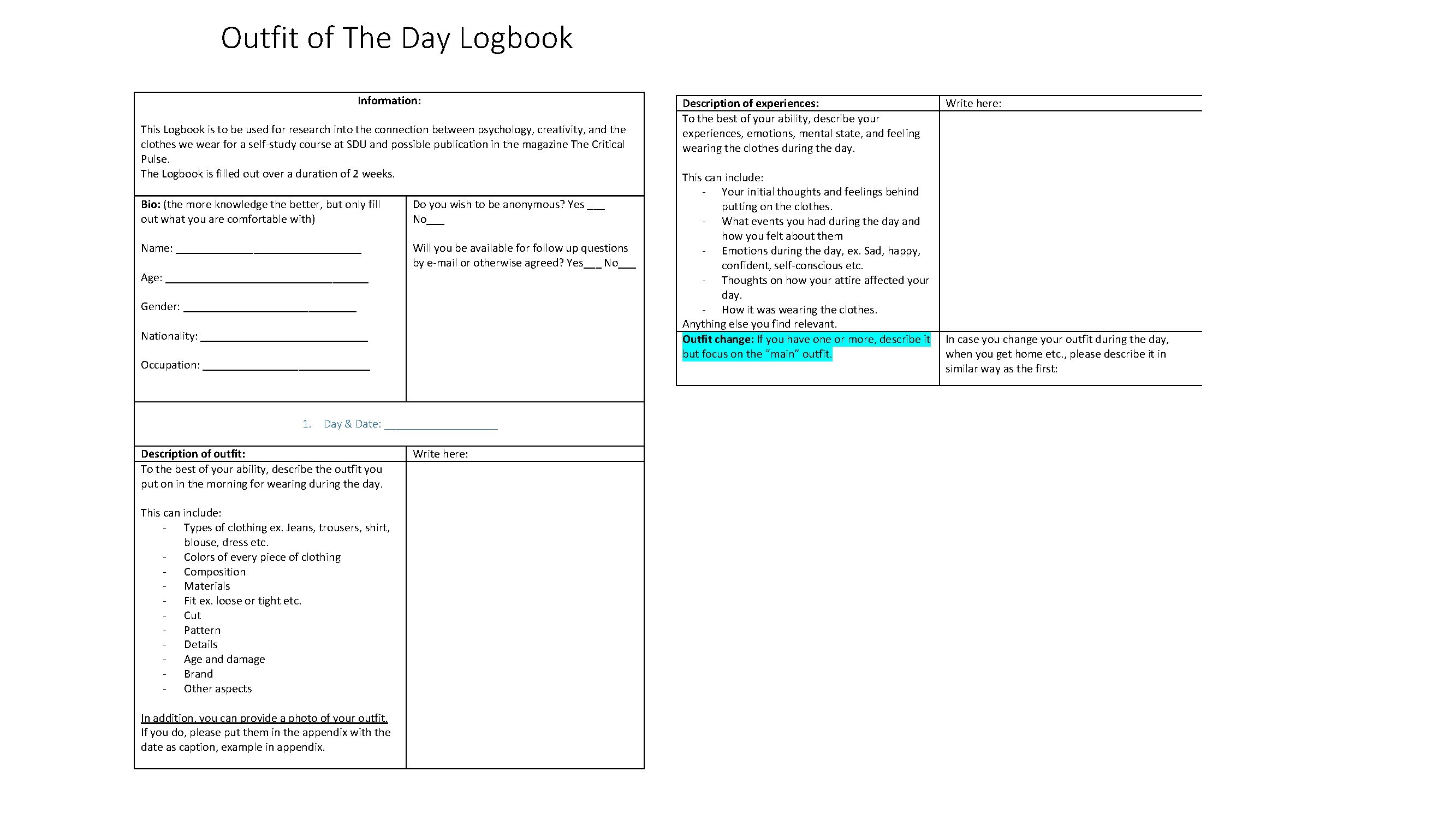

The "Outfit of the Day Logbook" is structured as a logbook or diary, where respondents can write down what they wear, their emotions, and any encounters they have during the day, and voluntarily take pictures to accompany their outfit descriptions. The first part includes demographic questions, such as age, gender, and occupation, which respondents are asked to answer if they feel comfortable doing so. Furthermore, it contains an anonymity clause and a description of the research purpose to address ethical concerns, ensuring that respondents understand they are encouraged to share only what they feel comfortable disclosing, particularly if they choose not to remain anonymous. All respondents in this paper signed a statement declaring that they would not be anonymous. However, prioritizing their anonymity was deemed essential.

The logbook has two columns: one describes the assignment, and the other is designated for written responses (Figure 1). Each day is represented by two rows: one for describing the outfit and the other for reflecting on the emotional experience that day. To keep the logbook open for interpretation and give the respondents some freedom, each column has only suggestions of what you could write about in keyword segments. This is to maintain some openness to the assignment while keeping it bounded in the form that requires them to fill out both a description of clothes and emotions. As a tool for qualitative research, it is based on ideas such as journaling, interviewing, and observation, similar to the wardrobe method and related approaches from anthropology (Bundgaard & Mogensen, 2018). The goal is not to elicit data aimed at achieving statistically significant results, but rather to explore the potential uses of this logbook format as an experimental approach to researching creative experiences. The logbook has 14 pages for 14 days to fill out, but it can be used for a longer or shorter period, depending on the material that needs to be gathered.

Some respondents requested the ability to write on their phones in their own notes or in other formats to customize their use of the logbook. As long as the structure of maintaining a logbook or diary is preserved, the method and underlying concepts remain intact and may, in fact, enhance the outcome of qualitative data obtained. As this paper examines creativity in everyday fashion practices, the investigative method should also prioritize encouraging creative freedom among respondents.

The three respondents utilized all 14 days of the logbook, which is the primary data collected for the analysis in this paper, attempting to provide examples of answers to the question: "what conditions enable or limit the possibility of creative expressions in everyday fashion practice?". The three respondents vary in gender and age, comprising two males and one female, with ages ranging from 27 to 38 years. Besides them, a group of young students under 18, all of whom are part of the LGBTQIA+ community, participated but for different reasons, did not complete the logbook, and are therefore not included in the paper because they presented insufficient data for comparison with the other respondents. Nevertheless, they had interesting ways of approaching the assignment as well as experiences with their clothes that could serve as inspiration for further work on perfecting the method itself, as well as research on the relationship between clothes, creativity, identity, and gender.

As an experimental study and, in this sense, a "prototype" for understanding everyday fashion practices, the respondents were chosen randomly through connections and references. Two male respondents were selected based on their prior participation in research on gender and fashion. The female respondent and younger participants were recruited through a call for individuals interested in exploring their relationship with the clothes they wear daily. No interviews were conducted, as the logbook was intended to provide the necessary data to examine possible outcomes. The respondent's demographic data is also of less interest within the scope of this paper.

6. Analysis of Logbooks

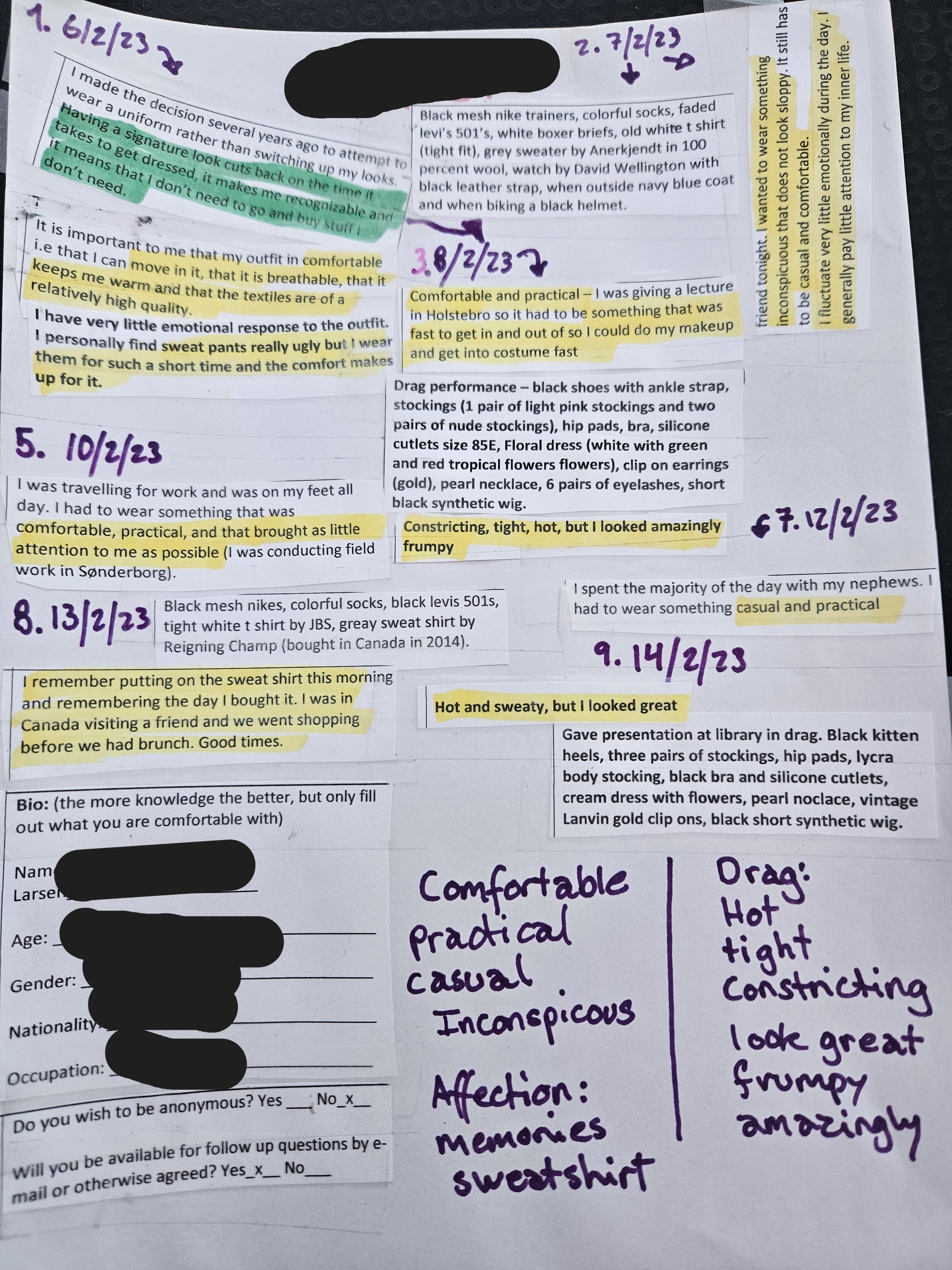

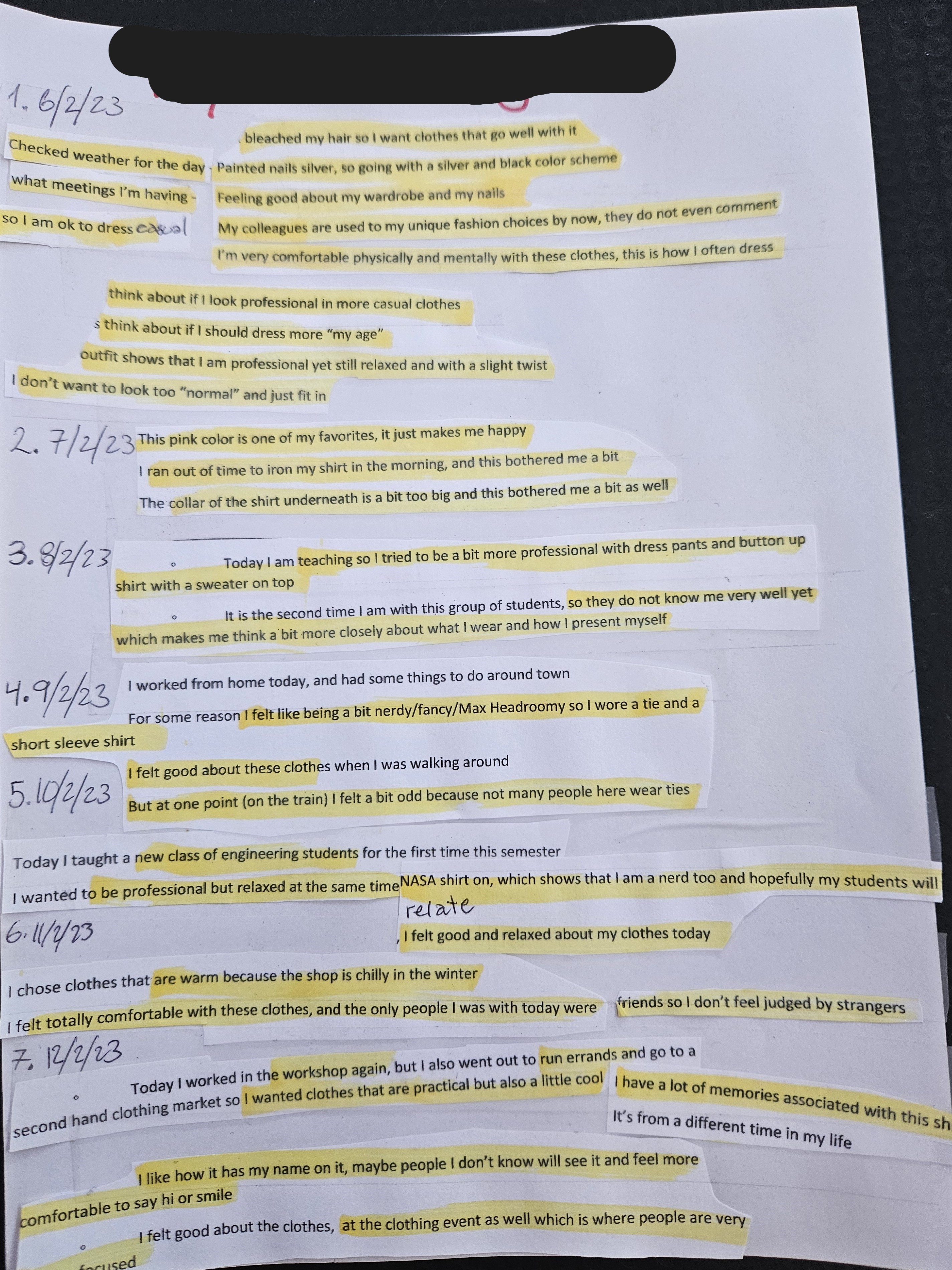

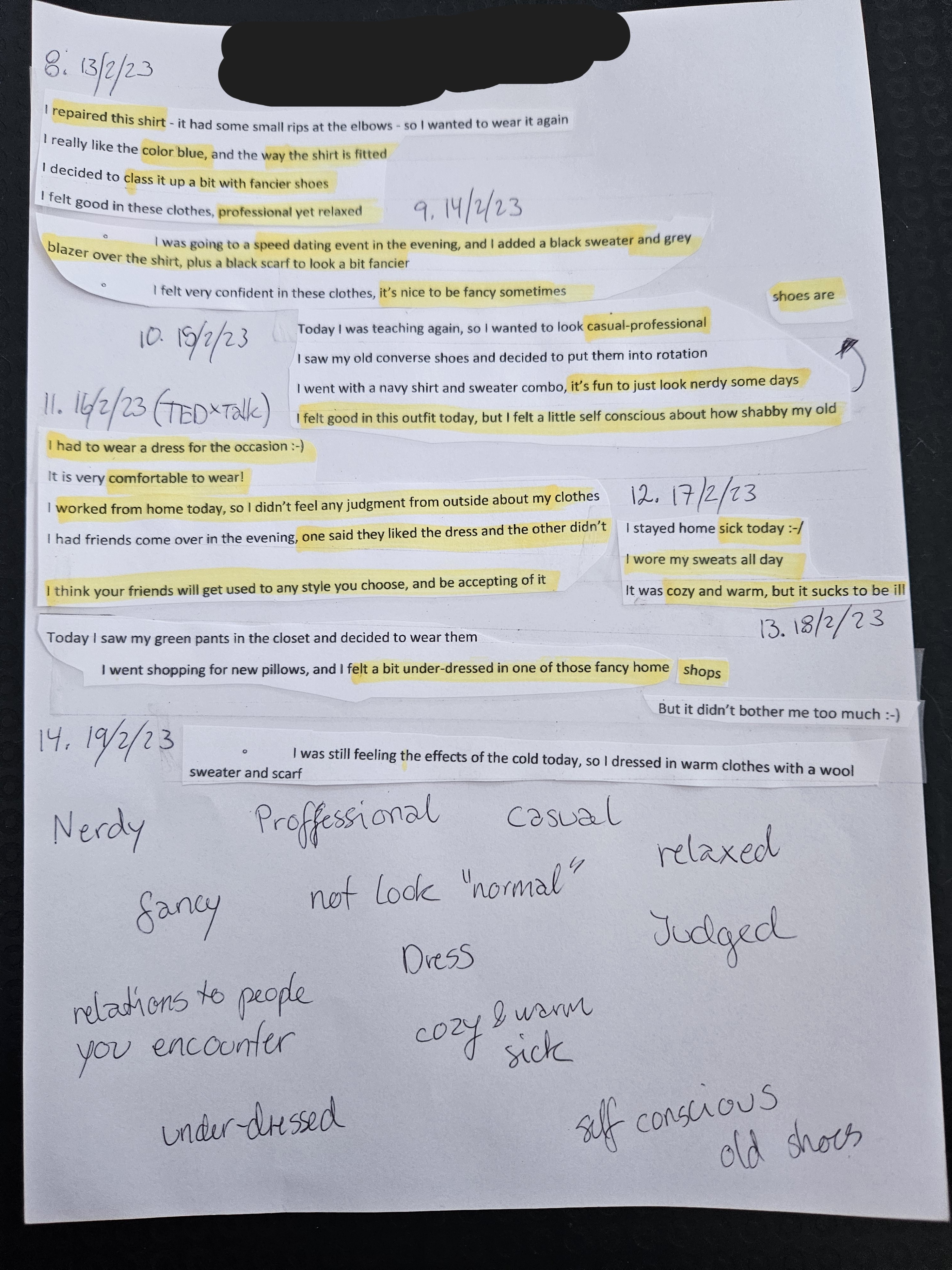

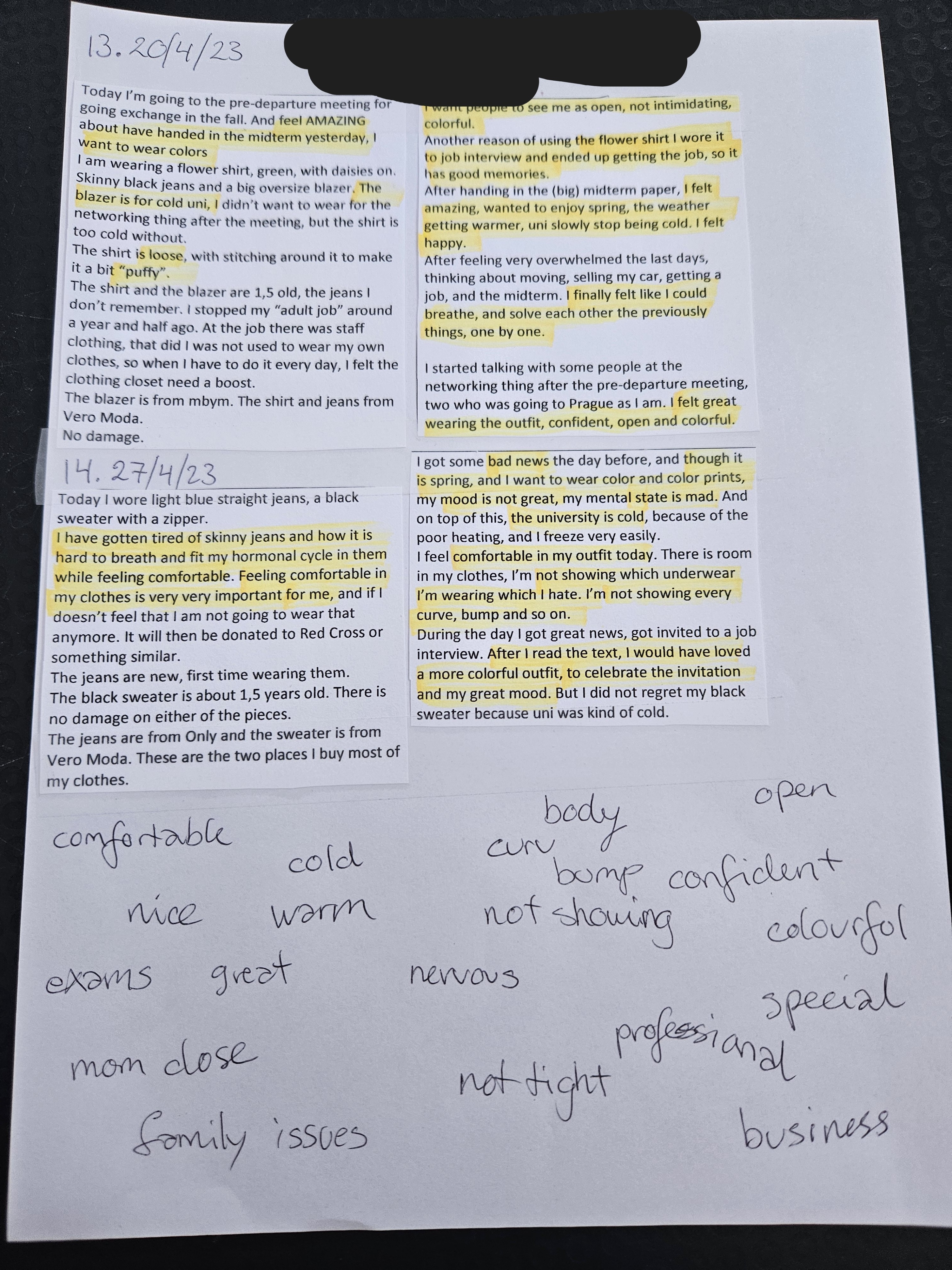

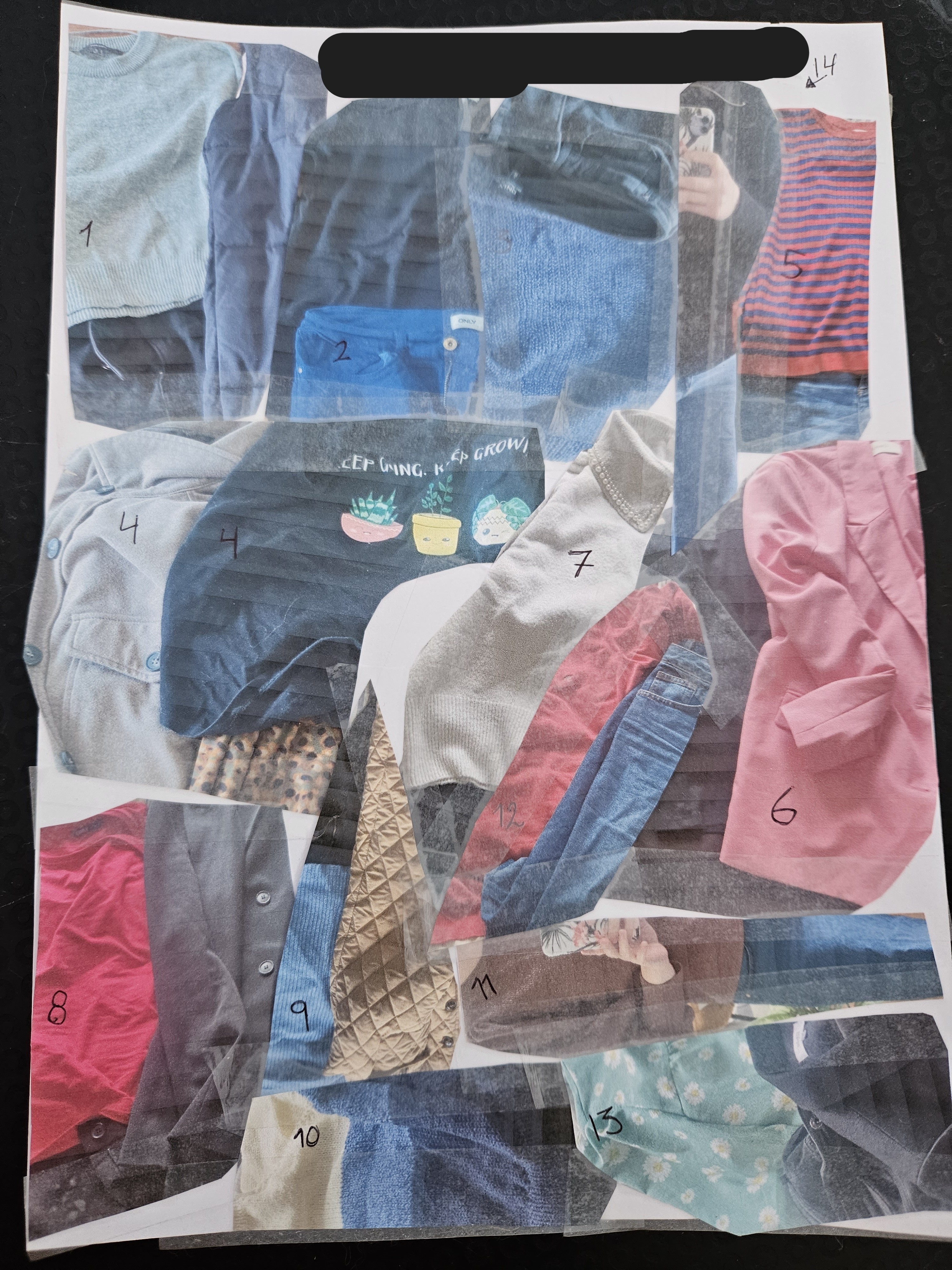

To analyze the data collected from the three complete logbooks, the analytical approach was inspired by method 19 from wardrobe studies (Fletcher & Klepp, 2017). This method involved identifying responses that revealed common themes or offered novel and surprising insights. The data from each respondent was compiled and presented as a collage, capturing their most significant reflections. These collages, used to create keywords for each participant, were especially descriptive advertisements that they frequently used to convey their feelings. In addition to their descriptions, two of the respondents included pictures, which were also compilied into a collage to provide a comprehensive view of their outfit choices side by side (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10).

One of the male respondents (Figure 1), referred to as Respondent 1, began his logbook by describing how, a few years ago, he decided to wear what he refers to as "a uniform". His reasoning was to save time, maintain recognizability, and reduce consumption. His uniform and overall clothing choices were centered on comfort, practicality, and blending inconspicuously into his daily life. This emphasis on comfort was closely tied to his workdays, during which he travelled extensively, as he described. He also mentioned that, although he finds sweatpants ugly, he appreciates the comfort they provide. He generally did not ascribe any emotional significance to his uniform, except on one occasion when he wore a sweatshirt purchased in Canada while visiting a friend, which evoked positive memories and thus held affectionate value. Respondent 1's descriptions of his outfits, emotions, and the contexts revealed little expression of creative processes.

Interestingly, Respondent 1 performed drag and had several performances over the weeks, during which his expression of creativity in fashion became more evident. In contrast to his usual, inconspicuous uniform, his drag outfits were described as featuring numerous creative elements, including objects, colors, and accessories, all combined to create his drag persona. While engaging in this fashion activity, his emotional response was ambivalent, oscillating between enjoyment of how striking and frumpy he looked and discomfort with the transformation process. His words to describe the experience were "tight", "hot", and "constricting". While Respondent 1 uses drag performance as a means of expressing creativity, he also experiences bodily and material constraints that limit both his creative process and enjoyment. Simultaneously, these conditions, along with social and societal acceptance, seem to influence his choice of a "uniform" that helps maintain a professional appearance. The ideas presented by Respondent 1 - expressing comfort in wearing garments like sweatpants, which he simultaneously described as "ugly" and inappropriate - contrast with his concept of a "uniform" deemed suitable for most situations, illustrating Goffman's notion of "front stage" and "back stage" (Entwistle, 2015). These social and societal conditions contribute to why we present different "selves" depending on the context. Specifically, there is the notion that we present ourselves in one way on the "front stage" in public, and another way on the "back stage" in private settings such as at home.

The other male respondent, Respondent 2, took daily notes on his phone, accompanied by pictures, instead of using the logbook itself while answering the same questions (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6). Many of Respondent 2's clothing choices were influenced by his daily schedule, as he took into account how his lectures or daily errands affected his decisions. Respondent 2 himself experiments with wearing dresses and skirts and mentions in the logbook that he tries not to look "normal". In his reflections, he noted that, looking back, he would have loved to be more creative and challenging. Many of his outfits focused on looking professional, casual, and nerdy when lecturing, especially when encountering students who were new to him. He was also self-conscious about wearing old shoes and feeling underdressed while visiting a home design store, influenced by the cultural environment and social relations surrounding him. Respondent 2 was sick while using the logbook, which clearly affected his outfits and limited his creativity due to bodily conditions, as his focus was on feeling warm and cozy instead of having fun with his style, as he usually does.

In many respects, these conditions demonstrate how Respondent 2 planned for the spaces he would encounter throughout his day, meaning he had to consider the differing norms of these environments, which varied significantly depending on whether he was teaching at the university or resting at home while sick (Entwistle, 2015).

The female respondent, Respondent 3, devoted much of the logbook to expressing her emotions and struggles over the weeks, including personal, family, workrelated, and study-related challenges (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, and Figure 10). These emotional descriptions revealed the significant impact of her social conditions on her choices and creativity. As she navigated daily struggles, she felt compelled to either dress colorfully to boost her confidence or choose comfortable clothing to alleviate stress. Unlike the other respondents, her descriptions consistently included considerations of the age and wear of the garments, indicating a greater concern for the longevity and materiality of what she wore. Like the other respondents, she selected her clothing based on the people she was meeting and the cultural context she was entering. However, interestingly, throughout the logbook, her choices were also heavily influenced by the weather. Seasonal changes, as well as environmental factors - such as the cold temperature in university classrooms - had a detrimental effect on what she felt able to wear. As the weather improved, her energy increased, and she became more engaged with creativity and enjoyment through wearing dresses, vibrant colors, and floral prints. These environmental changes, both in specific locations and the weather, conditioned the nature of her creative process while simultaneously affecting how she managed other conditions.

Another aspect that became clear when comparing the logbooks of the three respondents was the financial situation. While this warrants further analysis, it was clear that there were occupational differences, and therefore financial disparities, among them, with two being academics and one a student. This condition also limits or enables the extent of creative expression possible in relation to the types of clothing one can acquire. During the logbook period, Respondent 3 discovered second-hand shopping, which can foster greater creativity without imposing financial burdens. Additionally, both she and Respondent 2 described repairing their clothing as part of their practice.

The commonalities and differences among the respondents also help to highlight the conditions that shape creativity. While both Respondent 2 and Respondent 3 expressed a need for confidence and feelings of nervousness, Respondent 1 and Respondent 3 described various bodily or material conditions, such as tightness, revealing or concealing curves or bumps, and the importance of comfort.

Additional observations from the logbook that may offer insight into how the respondents engage with their clothing and sense of self include comparing the collage images - focusing on materials, colors, and other elements - with their corresponding emotional descriptions. For example, Respondent 3 described choosing a pink blazer to feel more confident when attending an interview - a material condition that enabled her creativity and enriched her day. This example also highlights an aspect of creativity explored by Kaufman and Glăveanu (2025), who write:

the emotional expression inherent in creativity can serve as a powerful tool for coping with adversity, helping individuals process difficult experiences and find new perspectives. This adaptability is particularly valuable in navigating life's uncertainties, making creativity not just a source of joy but also a key contributor to psychological resilience and overall well-being. (p. 3)

The idea that creativity in everyday practices can contribute to overall well-being is another area that warrants further exploration.

One aspect that did not emerge prominently in the respondents' answers - but remains integral to the cultural and societal/political context - is the issue of gender and race. These conditions influence the ways we consciously dress in response to our gendered experiences and embodied identities; these differences inform our decisions when selecting clothing (Entwistle, 2015). As noted, this topic has been explored by Entwistle and others, but it could be examined further through this proposed method in future studies, perhaps by including targeted questions or selecting respondents with these aspects in mind.

7. Conclusion on Further Possibilities

At the beginning of this paper, various theories on creativity were introduced with a particular emphasis on distributed creativity, which proved to be the most influential in developing the methodology. The study of the simple, everyday act of dressing - and the feelings associated with it - was presented as an attempt to highlight creative practice beyond traditional art forms or other fields typically regarded as domains of exceptional creativity. By investigating this common practice, the aim was to explore how respondents expressed creativity through their outfits and what factors enabled or limited their reflective creativity and sense of self. Although the scope of this paper was limited, it identified several conditions that appeared to influence creativity, many of which may be relevant to a wide range of activities and practices that either constrain or foster creative freedom.

This paper develops and proposes a method - "the logbook" or "Outfit of the Day Logbook" - which can be used to analyze the creative processes of individuals within their specific contexts. Grounded in both wardrobe studies and the theory of distributed creativity, the method highlights the social, emotional, and contextual factors that influence an individual's access to their creative potential. Furthermore, it serves as a qualitative research tool with interdisciplinary potential, applicable in fields such as consumer research, fashion design, and other related practices where engaging respondents in their emotional, social, and material contexts is essential. At this stage, the method remains an initial proposal and should be further refined or adapted to suit specific research questions and study designs.

A possible contribution of this work is the integration of qualitative methods from fashion studies and theoretical perspectives on creativity into our understanding of creative experiences and expressions in everyday life, rather than merely as finished products (Glăveanu & Beghetto, 2021). As Verger et al. (2024) note, "more recent theorisations are moving in the direction of a process approach to creation that moves away from viewing creativity as tied to the products created" (p. 277).

Within fashion studies, this method expands upon traditional wardrobe methods, which tend to focus on the object in a static place (the wardrobe). Although not the central focus of this study, given its emphasis on distributed creativity, the logbook method offers a more phenomenological approach, centering on the dressed body and its lived experience, thus framing clothing as objects in use by the subject. As Entwistle (2015) writes:

even the literature which takes account of the body tends to focus on the textual or discursive body and not the lived, experiential body that is articulated through practices of dress. Dress in everyday life is about the experience of living and acting on the body. (p. 5)

This perspective is crucial to understanding how creativity operates beyond the mind and the individualistic I-paradigm.

Grounded in the theoretical basis and supported by the findings from the analysis, this paper proposes a preliminary framework for investigating the degree of creative freedom within everyday fashion practices. The framework assesses how various conditions influence the ability to engage creatively with dress. Similar to the theory of distributed creativity, the analysis identified seven contextual conditions that may either enable or constrain the freedom to engage with one's creativity, specifically within fashion practices.

Conditions that limit or enable creativity include bodily, material, financial, social, societal/political, cultural, and environmental factors.

Each condition varies in its degree of influence and can be affected by others, resulting in an interdependent relationship that either facilitates or constrains the freedom to creatively fashion oneself. With further analysis, this framework could be refined and extended beyond fashion to other domains where assessing the conditions of creativity would be valuable.

Overall, the research provided insight into the importance of creativity within fashion practices, highlighting how we use clothing to construct our self-image. The analysis revealed that both internal and external conditions influence the extent to which respondents feel free to express their creativity. In particular, contextual factors such as cultural, social, and societal conditions were found to play a significant role in either limiting or enabling the respondents' confidence to experiment with their style, thereby shaping their everyday fashion practices. Just as weather, materials, and body influence our clothing choices, so too do the surrounding culture, the people we meet or socialize with, and the values and symbols embedded in society. These contextual factors critically shape the conditions that either limit or enable creativity within fashion choices. Understanding such conditions may empower us to challenge the limitations they impose, thereby fostering greater creativity and allowing more authentic expressions of self-identity. As we become more conscious of what we wear and why, we may be encouraged to reuse clothing that boosts our confidence, brings joy, and aligns with our style or body. By engaging more deeply with our creativity and becoming mindful of the conditions that influence us as creative consumers, we may also use our wardrobes in more sustainable ways. Recent research by Glăveanu and other authors explores how creativity can support degrowth - a concept that encourages reimagining society and questioning the assumptions underpinning current modes of resource use (Verger et al., 2024). They argue that we "need to contribute to imagining new ways of relating to materiality within our ecosystem" (Verger et al., 2024, p. 269) and propose a framework of creative preservation. They describe practices aligned with this approach as follows: "the creative preservation framework brings together practices that help to create a harmonious and sustainable cohabitation between humans and the things-in-the-world" (Himley et al., 2021, as cited in Verger et al., 2024, p. 269). Such cohabitation becomes possible through forms of creation that connect the past, present, and the future, thus ensuring the continuity of objects and ideas in a world of perpetual change (Verger et al., 2024).

Even within the scope of this small study, there is evidence of a respondent who focused on materials, second-hand clothing, and ways to extend the lifespan of garments. By focusing more closely on this subject and drawing on ideas about how creativity can be used not only to produce new goods but also to find new purposes for what we already have, future research could expand this line of inquiry. It would be valuable, for instance, to use a method like the logbook to better understand why individuals or collectives engage in practices that support degrowth, such as upcycling, second-hand shopping, or restyling used clothes (Verger et al., 2024). As the authors ask in the article: "what if the greatest way for thinking about how to improve the future was, in fact, thinking about preservation and renewal?" (Verger et al., 2024, p. 269).

This serves as just one example of how the method can be applied in practice by consumers, designers, fashion researchers, or the fashion industry. Beyond everyday practice, the research also offers insights into how a method situated at the intersection of fashion studies, psychology, and creativity theory can be utilized and further developed across other fields. While the use of journals or logbooks, as referenced in the development of the Logbook concept, is not new, this particular focus on recording emotional experiences alongside the material experience of embodiment presents a valuable approach for studying the relationship between body and mind within various everyday contexts.

texto em

texto em