Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Análise Social

Print version ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.214 Lisboa Mar. 2015

ARTIGO

Economic values, beliefs and behaviors: a regional approach1

Valores, crenças e comportamentos económicos: uma abordagem regional

Joao Carlos Graça*, João Carlos Lopes** e Cláudia Niza**

*SOCIUS, ISEG-UL, Rua Miguel Lupi, 20, Gab. 213 1249- 078, Lisboa, Portugal.

**SOCIUS, ISEG-UL, Rua Miguel Lupi, 20, Gab. 404 1249- 078, Lisboa, Portugal.

***ADVANCE, ISEG-UL, Rua Miguel Lupi, 20, Gab. 109 1249- 078, Lisboa, Portugal.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to identify relationships between economic value orientations, beliefs, and behaviors of agents, on the one hand, and differences between levels of economic development, on the other. Empirical analysis is based on a sample of Portuguese municipalities and corresponding parishes, organized in groups according to an urban-versus-rural typology and to levels of development as measured by GDP per capita. Different value orientations, beliefs, and behaviors were identified. Four clusters were considered: stabilization, economic nationalism, entrepreneurship, and consumerism. These clusters are related to the spatial dimensions considered.

KEYWORDS: economic values; economic beliefs; economic behaviors; Portuguese regions.

RESUMO

O propósito deste artigo é identificar relações entre orientações valorativas, crenças e comportamentos económicos, de um lado, e diferenças em níveis de desenvolvimento económico, do outro. A análise empírica está baseada numa amostra dos municípios portugueses e correspondentes freguesias, os quais foram organizados em grupos de acordo com uma tipologia urbano-rural e segundo níveis de desenvolvimento medidos através do PIB per capita. Identificámos diferentes orientações valorativas, crenças e comportamentos económicos. Foram subsequentemente considerados quatro clusters, os quais designámos genericamente como correspondentes a estabilização, nacionalismo económico, empreendedorismo e consumismo. Estes quatro clusters estão relacionados com as dimensões espaciais consideradas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: valores; crenças; comportamentos económicos; regiões portuguesas.

INTRODUCTION

The main purpose of this paper is to identify relationships between economic value orientations, beliefs, and behaviors of agents, on the one hand, and differences between levels of economic development, on the other.

We intend to contribute to the understanding of how psycho-sociological factors impact economic life. Values and beliefs are cognitive components essential in the framing of individuals relationships with the economy, even though the influence of these cognitive components on the economic behavior (specifically regarding saving, credit and investments) is very often overlooked in economic studies and has not yet been fully clarified.

Among other aspects, individual behavior and its determinants are deemed to be fundamental in understanding the processes of economic development (see Altman, 1993; 2006; 2008). Values, beliefs, and motivations may affect the efficiency of production, or how work efforts translate in terms of final economic output, and individuals conscious behavior may no doubt be determinant in matters of regional and national economic development (see Liebenstein, 1979; Porter, 2000). In other contexts economic beliefs have also been associated with pathological behaviors regarding money (Furnham, 1996; 1997) and with the support for different human values (Heaven, 2001).

Based on data collected from eight countries, Bastounis et al. (2004) showed that the control locus (the attribution of the causality of events to factors either external or internal to individuals) is closely related to the economic values supported, which is to say that the external control locus is mostly related to both the absence of trust in firms and to protest against the unfair treatment of workers.

We seek to contribute to:

1) Studying the structure of economic values in a Portuguese sample;

2) Describing the beliefs of Portuguese citizens regarding the functioning of the economy;

3) Identifying the prevalence of saving, credit, demand, and investment behaviors;

4) Understanding the connection between economic values, beliefs, and behaviors.

The empirical analysis presented is based on a sample of Portuguese municipalities and corresponding parishes, organized in groups according to an urban-versus-rural typology and to levels of development as measured by GDP per capita.

Using various empirical techniques, namely descriptive statistics, principal component analysis, and econometrics (General Linear Model – GLM), an in-depth study of values, attitudes, and behaviors is made. We identify different value orientations, beliefs, and behaviors according to either supply-side or demand-side, as well as predominantly State versus Private Sector orientations. Four clusters are considered, generically referred to as stabilization, economic nationalism, entrepreneurship, and consumerism. These clusters are related to the spatial dimensions considered. Parishes named rural, rural-urban, and urban show, albeit to a small degree, a prevailing orientation to the State, whereas developing parishes lean toward the private sector. Rural parishes are markedly consumerist, whereas in rural-urban parishes supply-side orientation prevails. Both urban and developing (corresponding to zones experiencing recent and considerable changes) occupy an intermediate position.

These results may be useful in providing important instruments of analysis and decision support for the implementation of regional policies, taking into account differences between rural and urban values, beliefs, and behaviors, as well as differentiated development needs.

Regarding the specificities of this paper, we should notice that, although several studies have been made concerning values, beliefs, and behaviors of the Portuguese population (e.g. Cabral et al. 2000, 2003; Vala et al. 2003; Vala and Torres 2006; Sousa 2009; Freire 2009; Silva 2013; see also ASP s/d), most of these studies use methods and approaches of a more strictly sociological character, somewhat different from our research strategy and methodology, which is more statistics-cum-econometrics inclined.

METHODOLOGY FOR DATA COLLECTION AND SAMPLE TREATMENT

The methodology for data gathering was based on a classification proposed by Pereira et al. (2008), combining a set of four indicators: 1) rural condition; 2) accessibility to goods and services; 3) income and modernity; 4) activity level and renovation. We made a cluster analysis classifying all the Portuguese parishes (4,037) as belonging to one of four distinct clusters. Supported by a Portuguese tradition of discussing urban issues (Ferrão, 2003; Marques, 2004, Salgueiro and Ferrão, 2005, among others), and specifically examining poverty, Pereira et al. argue that the results of their study confirm the territorys considerable heterogeneity in terms of rurality, accessibility, and economic context. These authors corroborate the coexistence and juxtaposition of the three internal territorial oppositions mentioned by Ferrão (2003): the north/south opposition, the littoral/interior opposition, and the archipelago-like configuration stemming from the emergence of urban agglomerations in the littoral and the interior, both north and south. Moreover, and still according to Pereira et al:

[ ] the results obtained [ ] suggest the interest of considering the four indexes [ ] as an alternative to the urban typology by INE & DGOTDU (1999). On the one hand, we verify a huge dispersion (with overlapping) of values in the indexes of rurality and accessibility for each one of the categories of the mentioned typology. On the other hand, and in spite of the detected association between the indexes of rurality and accessibility, the results suggest the specificity of both of them, and seem to confirm the interest of considering separately these two dimensions in the analysis [ ]. Finally, the diversity of the economic contexts of municipalities, in which parishes are integrated, points to the need to consider those two dimensions [income and modernity, as well as activity level and renovation] that are not reflected in the typology by INE & DGOTDU (1999) [Pereira et al., 2008, pp. 27-28].

The important notion thus arises that we should start from the four abovementioned indicators. The first of them uses five initial variables, organized into three dimensions: population size, demographic density, and heterogeneity of population – this last one being measured by levels of instruction, professional qualification, and proportion of natives in resident population (Pereira et al., 2008, pp. 10-11). For the second indicator two fundamental factors are considered: provision of goods and services, in general (referring to a total of 151 items regarding, among others, trade, communications, water supply and sewerage, health services, education, welfare, culture, and sports) as well as provision of public transports (Pereira et al., 2008, pp. 15-20). The third and fourth indicators are both based on a set of five factors: qualifications, demographic dynamics, income and productivity, industrial structure, and labor market (Pereira et al., 2008: 20 ff). For further methodological details, see Annexes 1, 2, and 3 in Pereira et al. (2008, pp. 30-32).

The four indicators mentioned thus allowed the construction of four statistical indexes based on the geographical characterization of each parish (regarding the rural condition and the accessibility to goods and services) and operating also at the level of municipalities membership, resulting from the two indexes of economic contextualization (designated as index of income and modernity and index of activity and renovation). After collecting data on the territorial units, each of the indexes was built using factor analysis techniques. All of these indexes confirm the existence of a largely heterogeneous territory in terms of dimension of rurality, accessibility, and economic context. After identifying the homogeneous parishes according to these criteria a cluster analysis was performed on a sample representative of Mainland Portugal.

MUNICIPALITIES ANALYSIS/CLASSIFICATION OF PARISHES

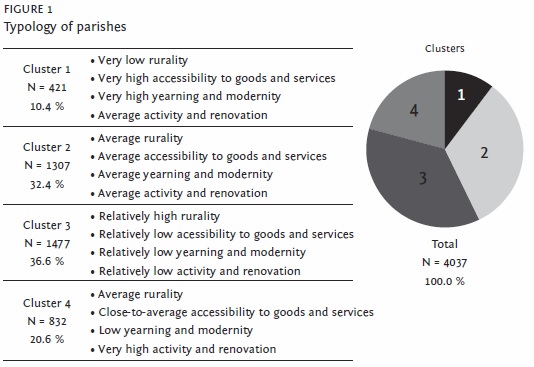

The starting point for the cluster analysis was a classification of Portuguese parishes according to the four indicators mentioned above: rurality, accessibility to goods and services, income-and-modernity, activity-and-renovation. Each parish has one value for each one of these indicators. The cluster analysis performed suggests the existence of four distinct clusters. The final result, with the description of the content and profile of each cluster, as well as the number of parishes by cluster, is in figure 1.

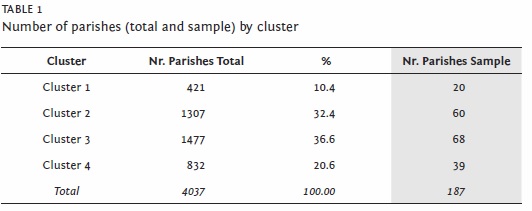

The cluster analysis was made at the parish level, given the fact that at the municipal level results were not statistically robust. Consequently, it was based on the results stemming from parishes that the municipalities were indirectly grouped. The results, with a confidence level of 95% and a sample error of 7%, are in Table 1.

The municipalities were studied with regard to their parishes distribution and number of parishes by cluster: this way we know how many parishes each municipality has in each cluster. We identify those that are the more homogeneous municipalities by cluster, that is, the ones with the parishes more concentrated in just one cluster. This categorization also allows an estimate of the resident population in each cluster.

At this stage the homogeneity of municipalities was not considered, but only which of them would be in each cluster, in order to allow us to approximate total population. The data concerning population by municipality were obtained from INE (2007). Using this procedure we have sufficient and adequate data for specifying our sample. The calculations made point to an adequate sample size of 1,000 individuals for Mainland Portugal: for a confidence level of 95%, a sample error of 3.1% and a Z value of 1.96, we obtained a sample size of 999.

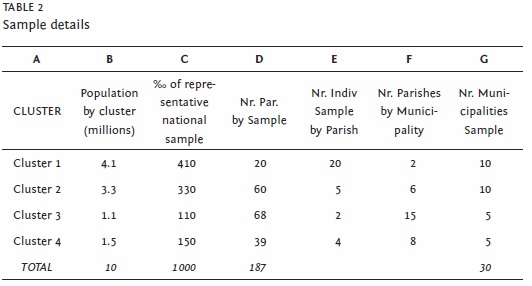

We selected 187 parishes distributed in the clusters. Given the estimate of population by cluster (B) and the correspondence of this value in the sample (C), it is possible to calculate the number of individuals by parish (see Table 2).

Due to the small number of parishes to select in clusters 2, 3, and 4, it is imperative to operate in our final analysis at the municipality level. Since the absolute values to collect in each parish are below 30, we must work with, respectively, 2 parishes per municipality in Cluster 1, 6 parishes per municipality in Cluster 2, 15 parishes per municipality in Cluster 3 and 8 parishes per municipality in Cluster 4 (Column F). Dividing the column D values by these values we obtain the number of municipalities of the sample in column G. For a representative sample of 187 parishes we have then a final sample of 30 municipalities. The numbers in the table are approximate, in order to simplify the calculations.

With this procedure the data are richer and more exact because we exclude from the municipalities the parishes that are not truly characteristic of that municipality, since they are located in another cluster. We start with a representative sample of parishes, which results in a further aggregation of municipalities.

SELECTION OF THE MUNICIPALITIES TO BE QUERIED

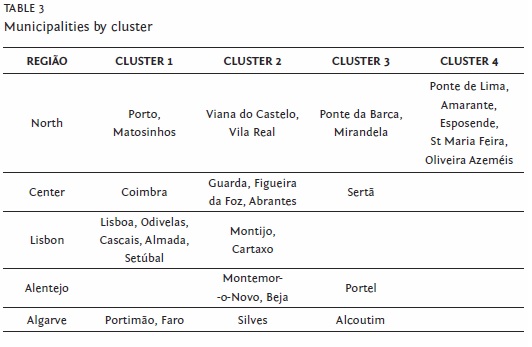

According to Table 2 Column G, we need 10 municipalities in Clusters 1 and 2, and 5 municipalities in Clusters 3 and 4. For the final selection we use the information about the parishes distribution, now in order to:

1. Choose the most homogeneous municipalities by cluster; and

2. Try to obtain municipalities from all the clusters in all the major regions of the country, whenever possible.

In Table 3 we have the distribution of municipalities by cluster, establishing the reference for the choice of parishes.

We have opted for one particular, feasible course of action that respected all the defined criteria. Within these municipalities, parishes were chosen to be considered based on their inclusion in the cluster to which the municipality belongs and in the number (column F) in Table 2.

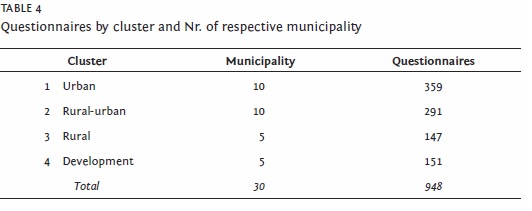

The aim of adopting this methodology was to allow us to proceed with the collection of data in a systematic way. After the selection of municipalities in which to implement the questionnaire, the field work occurred between April and September 2009. On the whole, 948 individuals participated in filling in the questionnaire in a valid way. These were divided by municipalities and clusters according with the results presented in Table 4.

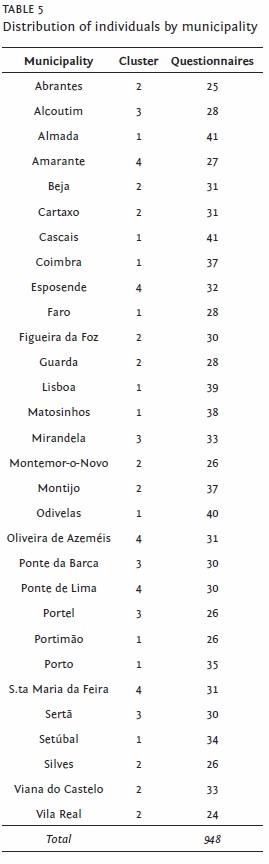

Each municipality received (on average) 32 questionnaires (minimum of 24 in Vila Real and maximum of 41 in Almada and Cascais). The distribution of individuals by municipality is shown in Table 5.

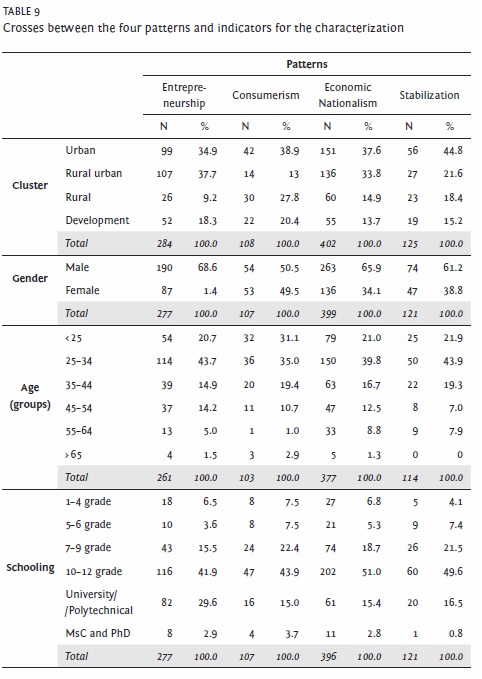

The sample comprises mostly women (64%). The participants minimum age is 16 years and the maximum 84, with an average of 34 (Standard Deviation, 11.9). For further detail concerning socio-demographic characteristics, see Table 9, below.

ECONOMIC VALUES, BELIEFS, AND BEHAVIORS: EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Based on the data and sample treatment previously described, several statistical and econometric methods were used in order to analyze the economic values, beliefs, and behaviors of the Portuguese population.

ECONOMIC VALUES

Regarding economic values, we adopted the Scale of Economic Values of OBrien and Ingels (OBrien et al., 1987), initially developed in the United States and subsequently applied with adaptations in several countries.

A study of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) has in our case uncovered a structure considerably different from the one originally defined by these authors, suggesting that the common ideas about economics are very different between Portugal and the US.

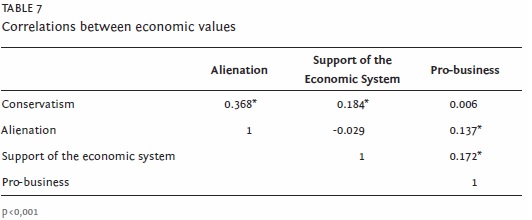

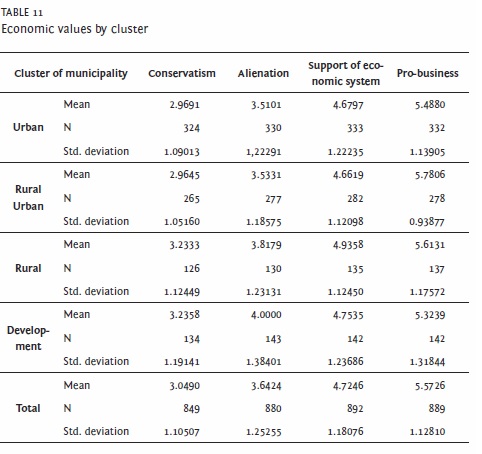

Four components were extracted [Bartletts Sphericity test=1397.943, p<.05, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin .723 p<.05; Minimum communality .382], explaining a total variance of 54.2%. These components are: 1) Conservatism, 2) Alienation, 3) Support of the economic system and 4) Pro-Business leaning. The composition of these components is shown in Table 6.

Based on the correlation analysis, one of the main conclusions is that Conservatism values are strongly connected with Alienation, and also with Support of the economic system, but to a lesser extent. Alienation is also positively correlated with Pro-Business values as well as the Support of the economic system (see Table 7).

ECONOMIC BELIEFS

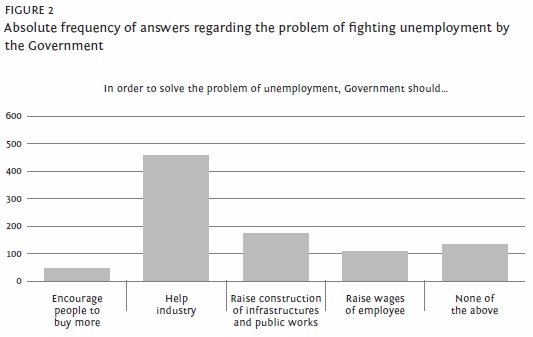

With the purpose of studying the economic beliefs of Portuguese citizens, we used the scale proposed in Leiser and Briskman-Mazliach (1996) regarding the common understanding of the functioning of the Economy. This scale measures the explanations given by participants in multiple choice answers about the unemployment-inflation trade-off, the causal factors being attributed to the individuals, the firms, or the State. A succinct descriptive analysis of the reported beliefs is in Figures 2 to 6.

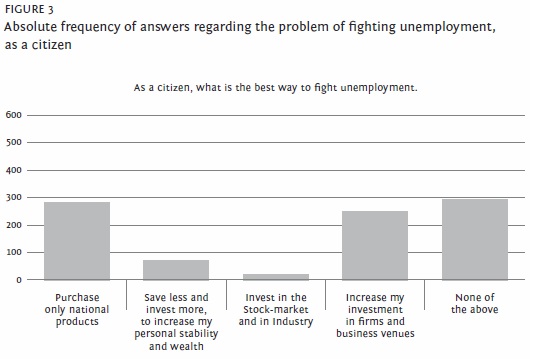

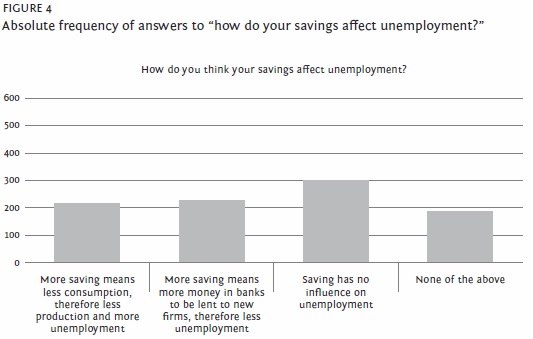

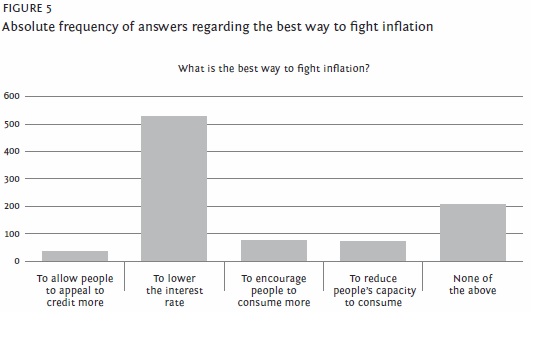

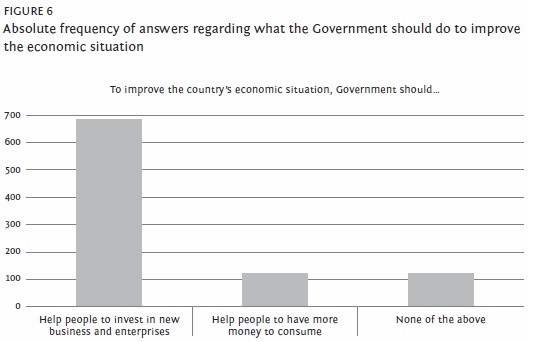

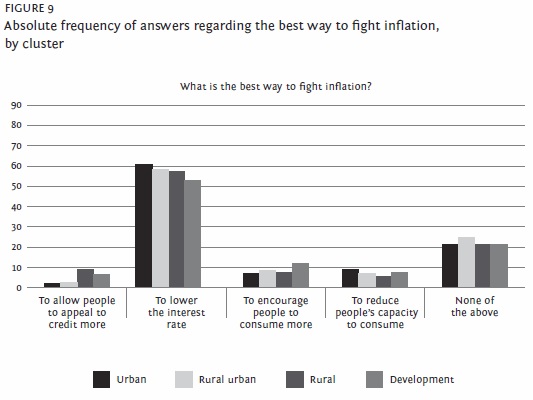

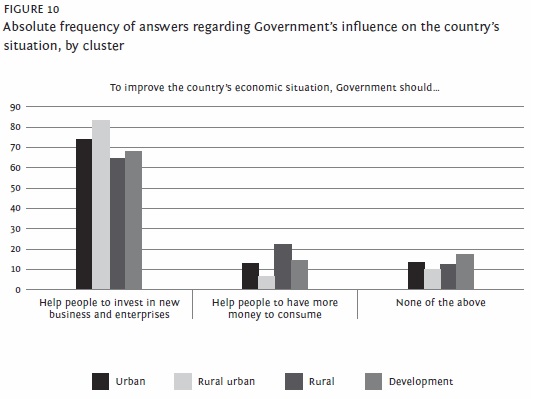

The majority of respondents think that in order to mitigate the unemployment problem the government should help firms, citizens should buy only domestic products, and investment in firms should be increased. On the other hand, most consider that saving has no impact on unemployment. The best strategy to fight inflation is, according to the majority of respondents, to lower the interest rate, which may indeed also be considered as a clear indication of economic illiteracy. Finally, the respondents agree with the idea that government should help people to invest in new businesses in order to improve the economic situation of the country.

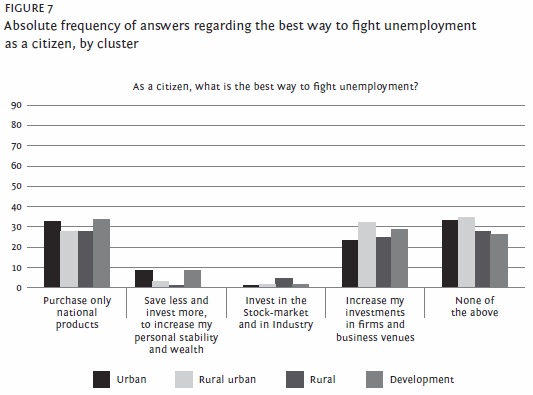

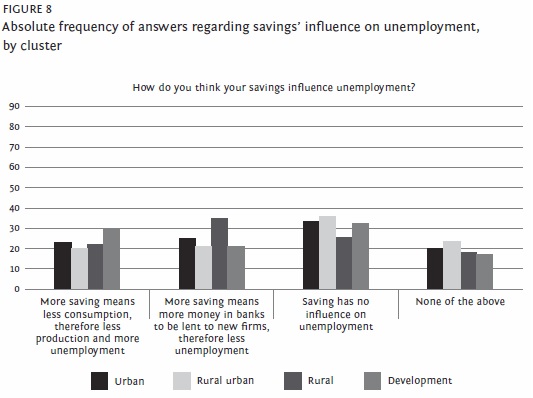

It is useful to consider each of the clusters individually. Analysis of the individuals economic beliefs by cluster reveals the existence of some significant differences. Although there are no differences about either how the government should solve the unemployment problem (χ2=15.777, p>.05) or about the causes of inflation (χ2=14.719, p>.05), there are differences across clusters about the way citizens should contribute to lower unemployment (χ2=30.669, p;=.002), about how savings influence unemployment (χ2 =17.614, p=0.04), about how to avoid inflation (χ2=23.537, p=.023), and about how the government should improve the economic situation of the country (χ2=28.250, p<.05) (see Figures 7 to 10).

The urban-rural cluster includes the participants that are less inclined to invest in their personal wealth and more inclined to investment in businesses as an instrument to fight unemployment. Concerning the way savings affect unemployment, development clusters participants believe mainly that saving more increases unemployment, while rural clusters members believe that saving more diminishes unemployment.

In order to avoid inflation, individuals of the rural cluster believe more than others that persons should have easier access to credit, but in the so-called development cluster the opinions are more supportive of the idea of increasing consumption. Last, rural-urban members are those who agree more that government should help people to invest with the aim of improving the financial situation of the country.

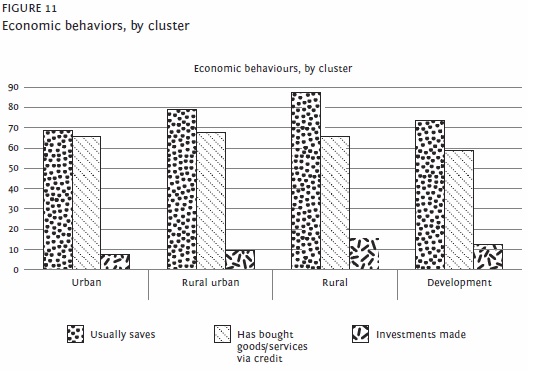

Regarding economic behaviors (Figure 11), the main conclusion is that the majority of respondents claim to save (71.84%) There are differences by cluster concerning the experiences of saving (χ2=20.904, p=0.000). Rural clusters individuals (87%) claim to save more than other clusters individuals, although all the values are high. More than half of the respondents say they have already bought through credit (62.34%). On the other hand, many have no kind of investment (84.81%) and this result is consistent by municipality (χ2;=40.145, p=.082). Regarding the act of buying through credit, there are no differences across clusters (χ2;=3.123, p=0.373), with values of magnitudes ranging from 60% to 70%. The values for investment are much lower and show only a marginal difference across clusters (χ2;=7.603, p=0.055). The clusters in which citizens claim to tend to invest more are, somewhat surprisingly, the rural (15.2%) and the development ones (12.4%).

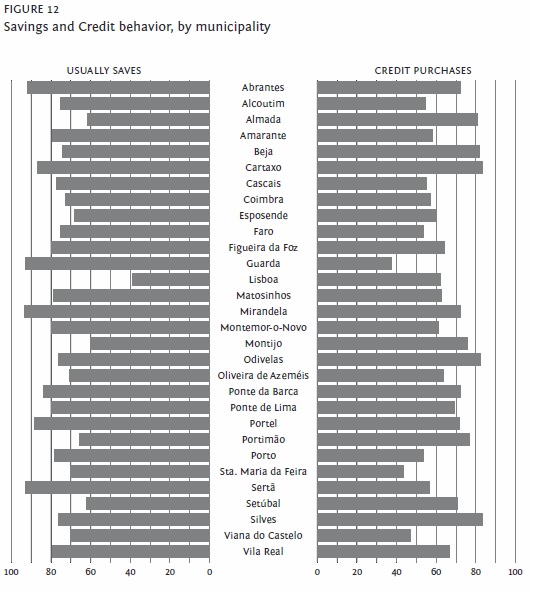

Regarding savings, there are significant differences (χ2;=68.812, p<.05) across municipalities. The municipality with participants claiming to be less prone to saving is Lisbon (38%), while the more savings-inclined are Abrantes (91%), Guarda (92%), Mirandela (93%), and Sertã (92%) (see Figure 12).

Concerning the use of credit, there are also considerable differences across municipalities (χ2=56.762, p=.02). Guarda, Santa Maria da Feira, and Viana do Castelo are those where the respondents mention less buying through credit, while Almada, Beja, Cartaxo, Odivelas and Silves are the municipalities with greater declared use of credit instruments (Figure 12).

PRINCIPAL COMPONENT ANALYSIS AND MULTIPLE CORRESPONDENCES: PATTERNS

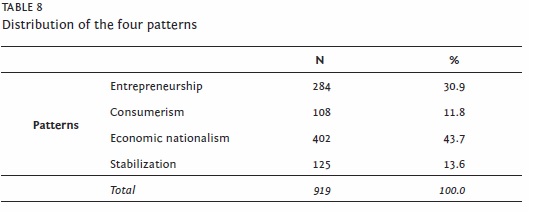

Analysis of multiple correspondences determines the relationships between different variables, reducing data complexity and thereby allowing patterns to emerge. Four patterns were found, organizing data in a way that allows an aggregate interpretation. The number of individuals corresponding to each pattern is shown in Table 8.

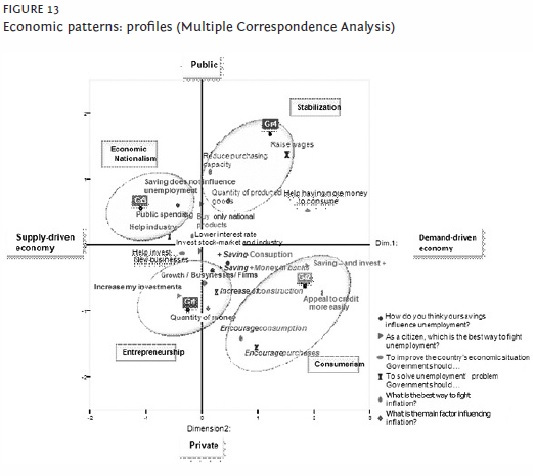

Dimension 1 (axis of abscissa – Figure 13) distinguishes the main perceived influences upon the Economy as being either Demand-side (+) or Supply-side (-). Dimension 2 separates the individuals who attribute the Economys prevalent direction to either the Public sector (+) or the Private sector (-). The interception of these dimensions identifies four patterns. A typical borderline case is the category referring to buy only national products, that is shared simultaneously by group 3 and group 4. The 4th quadrants categories increase of construction, encourage consumption and encourage purchases are features common to groups 1 and 2. The two categories corresponding to the indicator In order to improve the economic situation of the country, Government should are marked, and each of them is also associated with a pair of groups, such as pointed-out by the double arrows.

Next, a brief description of each pattern is made. Pattern 1 combines an orientation to the supply side with dominance of the private sector – firms growth – that was named Entrepreneurship. Pattern 2 is characterized by an orientation to the demand side and also leaning to the private sector – consumption and use of private credit – which we designated as Consumerism. Pattern 3 is also related to the demand side, but in this case connected with the public sectors influence; it was termed Stabilization as it combines the drive for wage growth with a concern vis-à-vis the reduction of consumptions capacity. Finally, group 4, combining the influence of the public sectors supply with the defense of public spending reduction, was named Economic Nationalism.

PATTERNS, ECONOMIC VALUES, AND TYPES OF MUNICIPALITIES

Patterns and types of municipalities

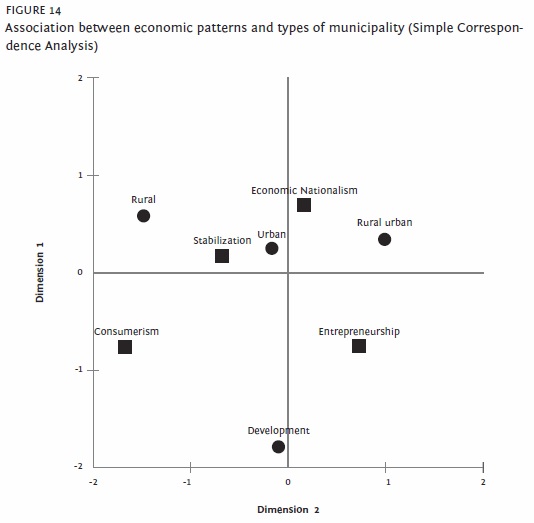

There are note-worthy differences by cluster (χ2;=45.012, p<.05), gender (χ2;=12.111, p=.007), and schooling (χ2;=32.054, p=.06), but not by age (Table 9). The associations between these variables are shown in Figure 14. The Development cluster is connected to both Entrepreneurship and Consumerism. The Rural-urban cluster is especially associated with Economic Nationalism. The Urban cluster has associations with the patterns of both Economic Nationalism and Stabilization, while the Rural cluster links only with the latter.

Women are associated with patterns of Entrepreneurship and Economic Nationalism, while men are closer to Consumerism. Regarding education, extreme levels (1-4 years of elementary school, together with third-level graduates) are associated with Consumerism, professional-technical education is mostly related to Nationalism and Economic Stabilization, and Entrepreneurship denotes particularly individuals with secondary school degrees. Cross-relationships of socio-demographic characteristics are shown in Table 9.

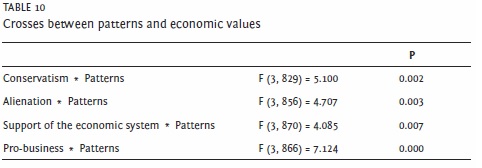

Patterns and economic values

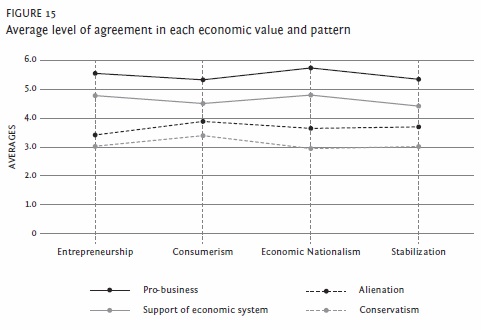

The economic values reported by the participants have mean values that differ significantly by pattern (Table 10) and the profile of each pattern concerning the four components of economic values found is shown in Figure 15.

Regarding Conservatism there are significant differences between the pattern of Consumerism and the other three patterns (p<0.05). On Alienation, meaningful differences are also identifiable between the pattern of Consumerism and Entrepreneurship (p<0.01). Concerning Defense of the economic system we notice significant differences between the patterns of Economic nationalism and Stabilization (p;<0.05). On Pro-business, the pattern Economic nationalism presents significant mean differences with both the pattern Stabilization (p<0.05), and the pattern of Consumerism (p<0.001).

There is an association, on the one hand, between Conservatism and Alienation and, moreover between Pro-business and Support of the economic system.

Economic values and types of municipalities

As for municipalities, those belonging to Rural and Development clusters are more associated with the values of Conservatism and Alienation. The Rural-urban municipalities have strong links to the values of Pro-business and Support of the economic system. With regard to the municipalities of the Urban type, there are average levels below the overall average, and these are clearly identified with each of the economic values (Table 11).

Patterns, economic values, and types of municipalities

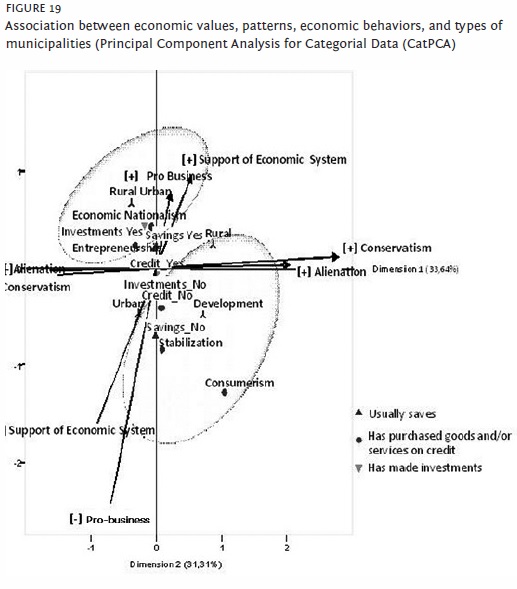

To further analyze patterns, economic values, and types of municipalities, we used an analysis designated CatPCA (Principal Component Analysis for Categorical Data), which is a variety of factor analysis allowing the conciliation of quantitative variables with qualitative variables. Quantitative variables are represented by vectors and qualitative variables by points that match their categories.

As for the positioning of the patterns, CatPCA shows that the pattern of Consumerism is clearly associated with the values of Alienation and Conservatism. The same type of association, although less intense, is also found for the pattern of Stabilization.

The patterns that point to Entrepreneurship and Economic Nationalism are mostly associated with Pro-business and Support of the economic system values, exactly the opposite of the patterns of Stabilization and Consumerism.

Continuing the exploration of the associations between economic values, patterns, and types of municipality, let us now assume that we wish to test the model of moderation. The central question is: does the variable type of municipality convey any influence or effect on the relationship between patterns and economic values? We test the model illustrated in Figure 16.

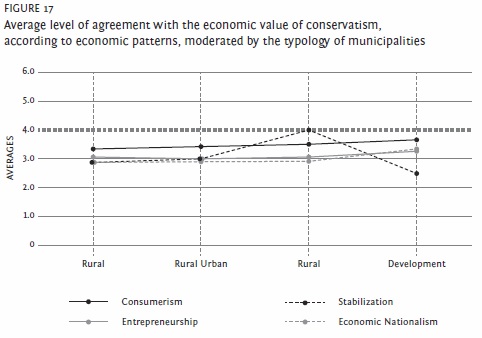

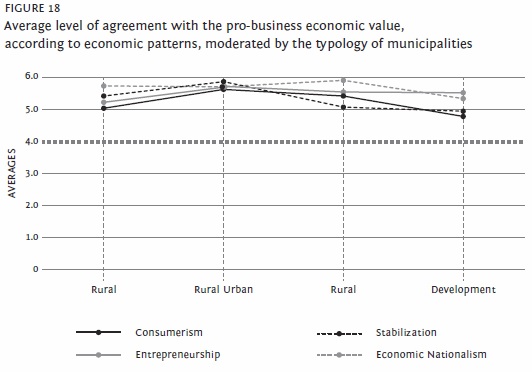

It is only interesting to determine whether the effect of interaction is significant. Through the results obtained with an econometric analysis using the General Linear Model (GLM) we conclude that there is a moderating effect (interaction) to the economic values: Conservatism (F;=2,405, p=0.011) and Pro-business (F;=2,097, p=0.027). The profile plots (Figures 17 and 18) show the contours of the interaction effect in each of the two situations with significant effect.

Returning to the relationship between economic values, patterns, and types of municipality, we add the economic behaviors (Q5 – do you usually save?, Q10 – have you already bought goods and services on credit?, Q17 – do you have investments?). To this end a further analysis of the CatPCA type (Figure 19) was made. Given the configuration already obtained in the earlier CatPCA, it is perceptible that the buying behaviors involving having made investments, having borrowed, and having savings are associated with the profile that combines the values of pro-business and support of the economic system with the patterns of pro-investment and counter-investment, and also the predominance of municipalities of rural-urban type.

The absence of those economic behaviors is mostly associated with another profile. The pattern of consumerism is more associated with the refusal of the economic behaviors in question. The agreement with values such as alienation and conservatism is also worth noting. This seems to be the profile of both rural and developing municipalities.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This paper seeks to identify relationships between evaluative economic orientations, beliefs, and behaviors of agents and differences in levels of regional development. The empirical analysis was based on a survey of almost 1,000 persons living in Portuguese municipalities (and respective parishes), that were selected in order to construct a sample representative of the whole nation, according to a rural/urban typology and also taking into account the level of development as measured by GDP per capita.

We identified patterns considering a higher prevalence of orientations for either the supply-side or the demand-side, as well as orientations predominantly for the State or for the market. This methodology allowed us to construct four clusters: stabilization, economic nationalism, entrepreneurship, and consumerism. These clusters were then framed in a context of spatial analysis, and crossed with different typologies at this level of analysis.

A key finding is that the parishes named rural, rural-urban, and urban show an orientation (although in general not very marked) that emphasizes the role of the State, while the parishes described as in development (i.e., those belonging to regions that have recently undergone a strong structural change) are markedly oriented to the market.

Another important conclusion, and indeed somewhat unexpected, is that the rural parishes are markedly consumerist, while the rural-urban are dominated by an orientation toward supply. Interestingly, both urban and developing regions occupy, regarding this criterion, an intermediate position. In fact, the cluster in development is associated with both entrepreneurship and consumerism. The rural-urban cluster is particularly related to economic nationalism. The urban cluster has associations with patterns of economic nationalism and of stabilization, while the rural cluster relates only with the latter.

Regarding the intersection with values, we found that the pattern of consumerism is clearly associated with alienation and conservatism. The same type of association, though less intense, is shown by the pattern of stabilization. The patterns pointing to entrepreneurship and economic nationalism are predominantly associated with pro-business and support of the economic system values, exactly the opposite of the patterns of stabilization and consumerism.

Concerning the moderation according to the typology of municipalities, we found the important fact that the values of pro-business and support of the economic system are linked with the municipalities of the rural-urban type. The absence of these economic behaviours is mostly associated with the other profile. The agreement with values such as alienation and conservatism is also worth noting. This seems to be the profile of both rural and developing municipalities.

These results are important for the formulation of economic and social policies taking into consideration the regional dimension, which is, in our opinion, a crucial element for a better knowledge of economies and societies, given the significant geographical differences in economic values, beliefs, and behaviors.

Last, we should mention the important aspect that the enquiry supporting this study was carried out before the ongoing economic crisis or in its very early stages, and as a consequence, an important final suggestion is that an updating/enlargement of the field research that we have undertaken is likely important in order to assess both elements of permanence and possible shifts in mentalities accompanying changes in economic situations, and vice-versa.

REFERENCES

ALTMAN, M. (1993), Human agency as a determinant of material welfare. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 22 (3), pp. 199-218. [ Links ]

ALTMAN, M. (2006), Human agency and free will: choice and determinism in economics. International Journal of Social Economics, 33 (10), pp. 677-697. [ Links ]

ALTMAN, M. (2008), How much economic freedom is necessary for economic growth? Theory and evidence. Economics Bulletin, 15 (2), pp. 1-20. [ Links ]

ASP (s.d.), Programa Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses, available at http://asp.ics.ul.pt/, [last accessed at 17-3-2014]. [ Links ]

BASTOUNIS, M., LEISER, D., ROLAND-LÉVY, C. (2004), Psychosocial variables involved in the construction of lay thinking about the economy: results of a cross-national survey. Journal of Economic Psychology, 25, pp. 263-278. [ Links ]

CABRAL, M.V., VALA, J., FREIRE, J. (orgs.) (2000), Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses 1 – Trabalho e Cidadania, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

CABRAL, M.V., VALA, J., FREIRE, A. (orgs.) (2003), Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses 3 – Desigualdades Sociais e Percepções de Justiça, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

FERRÃO, J. (2003), Dinâmicas Territoriais e Trajectórias de Desenvolvimento, Portugal 1991-2001. Revista de Estudos Demográficos, 34, pp. 17-25. [ Links ]

FREIRE, J. (org.) (2009), Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses 9 – Trabalho e Relações Laborais, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

FURNHAM, A. (1996), Attitudinal correlates and demographic predictors of monetary beliefs and behaviours. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17 (4), pp. 375-388. [ Links ]

FURNHAM, A. (1997), The half full or half empty glass: The views of the economic optimist vs. pessimist. Human Relations, 50 (2), pp. 197-208. [ Links ]

HEAVEN, P. (2001), Economic beliefs and human values: Further evidence of the two-value model?. Journal of Social Psychology, 130 (5), pp. 583-589. [ Links ]

INE (2007), Anuário Estatístico, Lisbon. [ Links ]

LIEBENSTEIN, H. (1979), A branch of economics is missing: micro-micro theory. Journal of Economic Literature, 17, pp. 477-502. [ Links ]

LEISER, D., BRISKMAN-MAZLIACH, R. (1996), The Economic Model Questionnaire, Beer Sheva, Ben-Gurion University. [ Links ]

MARQUES, T.S. (2004), Portugal na Transição do Século. Retratos e Dinâmicas Territoriais, Oporto, Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

OBRIEN, M.U., INGELS, S.J. (1987), The economics values inventory. The Journal of Economic Education, 18 (1), pp. 7-17. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, E., PEREIRINHA, J., PASSOS, J. (2008), Desenvolvimento de índices de caracterização do território para o estudo da pobreza rural em Portugal continental. Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais, 21, pp. 3-32. [ Links ]

PORTER, M. (2000), Attitudes, values, beliefs, and the microeconomics of prosperity. In L.E. Harrison & S.;P. Huntington (eds.), Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress, New York, Basic Books, pp. 14-28. [ Links ]

SALGUEIRO, T.B., FERRÃO, J. (coord.) (2005), Geografia de Portugal. Sociedade, Paisagens e Cidades, vol. 2, Mem Martins/Rio de Mouro, Círculo de Leitores. [ Links ]

SILVA, F.C. (org.) (2013), Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses 12 – Os Portugueses e o Estado-Providência: uma Perspectiva Comparada, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

SOUSA, L. (org.) (2009), Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses 8 – Ética, Estado e Economia: Atitudes e Práticas dos Europeus, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

VALA, J., CABRAL, M.V., RAMOS, A. (org.) (2003), Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses 5 – Valores Sociais: Mudanças e Contrastes em Portugal e na Europa, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

VALA, J., TORRES, A. (org.) (2006), Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses 6 – Contextos e Atitudes Sociais na Europa, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

Received 29-04-2013. Accepted for publication 16-05-2014.

NOTAS

1 Financial support from FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia), Portugal, is gratefully acknowledged. This article is part of the research project Values, Beliefs and Economic Behaviors, PTDC/SDE/73494/2006, SOCIUS, ISEG-UL (2007-2009), and of the Strategic Project, PEst-OE/EGE/UI0436/2011, UECE, ISEG-UL.