Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

CIDADES, Comunidades e Territórios

versão On-line ISSN 2182-3030

CIDADES no.37 Lisboa dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.15847/citiescommunitiesterritories.dec2018.037.art02

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Housing in “intramural favelas”: Considerations on new forms of urban expansion in contemporary times

Habitação nas "Favelas Intramuros": Reflexões acerca de Novas Formas de Expansão Urbana

Cláudia SeldinI; Juliana CanedoII

[I]Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. e-mail: claudia.seldin@gmail.com.

[I]Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. e-mail: j.canedo@campus.tu-berlin.de.

ABSTRACT

This paper develops a deeper look into new residential appropriations of space in marginalized areas of a large Brazilian city, while highlighting the subjective importance of housing and its meaning beyond the idea of shelter. Firstly, it presents a brief history of Rio de Janeiro's favelas – the local version of slums – and its relationship with vacant land over the past 100 years. Then, it explains the value of self-built housing and its contribution to the consolidation of multiple and hybrid territories, highlighting their subjective character. Lastly, it presents a case study called Portelinha, located in a set of favelas known as the Maré Complex, stressing how this mixed occupation has transformed the local urban fabric, leading to the emergence of what is referred to as an “intramural favela”. This phenomenon consists of the self-construction of a smaller-scale set of houses within the walls of a former factory turned into an industrial void in the 1990s. The analysis shows how this housing appropriation is articulated with other activities, especially cultural ones, leading to a diversity of social actors, alliances and conflicts, turning it into a real disputed territory. Cases like this reflect the challenges with which architects and planners need to deal with when working in the unequal urban contexts that are so common in the Global South.

Keywords: housing, favelas, deindustrialization, Rio de Janeiro, occupation.RESUMO

Este artigo desenvolve um olhar mais profundo sobre novas apropriações residenciais do espaço em áreas marginalizadas de uma grande cidade brasileira, destacando a importância subjetiva da habitação e seu significado para além da ideia de abrigo. Em primeiro lugar, apresenta uma breve história das favelas do Rio de Janeiro e sua relação com as terras desocupadas nos últimos 100 anos. Em seguida, explica o valor da habitação própria e sua contribuição para a consolidação de territórios múltiplos e híbridos, evidenciando seu caráter subjetivo. Por fim, apresenta um estudo de caso chamado Portelinha, localizado em um conjunto de favelas conhecido como Complexo Maré, ressaltando como essa ocupação mista transformou o tecido urbano local, levando ao surgimento do que é chamado de “favela intramural”. Esse fenômeno consiste na autoconstrução de um conjunto de casas de menor escala dentro das paredes de uma antiga fábrica que se transformou em um vazio industrial nos anos 90. A análise mostra como essa apropriação habitacional é articulada com outras atividades, especialmente culturais, levando a uma diversidade de atores sociais, alianças e conflitos, transformando-a em um real território disputado. Casos como esse refletem os desafios com os quais arquitetos e planejadores precisam lidar quando trabalham nos contextos urbanos desiguais que são tão comuns no Sul Global.

Palavras-chave: habitação, favelas, desindustrialização, Rio de Janeiro, ocupação.

1. Introduction: about housing in Brazilian favelas

The theme of housing, within the field of Urban Studies in Brazil, was studied for most of the 20th century in a limited or fragmented way due to the strong inheritance of the local modernist movement, in which the “act of dwelling” was seen predominantly as a function; as a simple architectural element that composed a city. For a long time, the value of formal housing that originated from plans and architectural projects was more highly regarded in the field, while informal, do-it-yourself constructions in lower-income regions, especially in the favelas [3] and peripheral neighbourhoods, were often considered a problem and a disruption to the landscape by local authorities and many planning professionals. According to Silva (2001), the discussion around the importance of the favelas' permanence emerged parallel to the official policies focusing on removing and repressing them. Still, initiatives aimed at the improvement of their inhabitants' quality of life through isolated urban interventions were introduced in certain political contexts and were often carried out or supported by the Catholic Church and NGO-like movements. In fact, records of proposals for urban improvements in favelas of Rio de Janeiro, where they have existed for over 100 years, date back to the 1920s and 1930s (especially during Mayor Pedro Ernesto's term, from 1931 to 1936). However, these improvements were offered in exchange for votes and political support from residents, highlighting the perception of favelas as key electoral pools since an early stage.

In the last few decades, the perception about the importance of informal housing to this country's urban development has changed. More studies emerged taking the diversity of existing dwelling options into account and stressing the need to understand and incorporate official policies in the housing solutions that emerge in the favelas. Contemporary research aims to understand and mitigate the various stigmas connected to these areas, recognizing them as integral parts of the cities, while defending that they represent complex and diverse realities that have been tackled in a homogenous or simplistic manner. This renewed view is essential because, regardless of the many urban interventions observed nowadays, favelas are still growing in area and number, not only in Brazil, but worldwide (Davis, 2006) and their inhabitants' quality of life is still precarious, as is their access to basic rights.

Considering the leading role of favelas in contemporary times, this article aims at presenting a hybrid appropriation of space in one of the biggest favela complexes in the city of Rio de Janeiro – the Portelinha Occupation in the Maré Complex. Its main goal is to discuss the process of spatial appropriation itself, proving that, more than an agglomeration of houses, these self-built constructions are full of symbolism and features that go beyond the simple access to shelter. Our intention is to show that, despite the lack of apparent or traditional urban planning or design behind the development of the favelas, particularly in the case of Portelinha, there is in fact an intentional action towards the transformation of urban space. What may be observed is that more than just housing is created through the construction of houses. Portelinha also witnessed the creation of public places, places for exchange and sociability, places full of meaning, places of disputes, conflicts and negotiations. What emerges is more than just space. It is a complex territory that guides the lives of its residents and visitors. In essence, this case study can help urban professionals to reflect upon the observation of a given reality and raise questions about the need for a new and improved planning view in developing cities, focusing on existing bottom-up initiatives that emerge as responses to immense urban and social problems.

The methodology behind this research was divided into two different phases. The first one was the contextual analysis of the existing literature on the subjects of the history of Rio's favelas, the symbolic dimension of housing, the nature of hybrid territories and the local aspects of the Maré Complex, as a means to present the relevant cultural, social and political contexts that make up the process of production of space involved in the urban phenomena of post-industrial housing and “intramural favelas”. The idea here was to address the concept of housing from a broader point of view, considering the many meanings attached to it, exploring its symbolic importance and considering its subjective character – mainly, the relationship between the home and its residents. This contextual analysis took on an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating reflections from other fields of knowledge (such as History, Sociology and Cultural Geography), essential to the understanding of such a complex object.

The second phase was the observation of the Portelinha case study at the Maré Complex through an ethnographic approach in search of qualitative results. This phase included the practice of observant participation and direct observation through field research, and the use of perspective analysis. Several visits to the site known as the Portelinha Occupation took place over many years, beginning in 2007. They were accompanied by interviews to the residents and leaders of two of the existing cultural groups and by photographic records that showed the evolution of the local constructions and its transformations throughout this time. Most of the facts concerning this case have been provided through these interviews, as there are little documented data about it in the existing literature.

Documenting and analysing housing appropriations in Brazil is particularly important because the country suffers from an intensive housing deficit (approximately 6,3 million in 2015) [4] coupled with ironically high figures for empty properties (7,9 million in 2015). [5] This happens because housing occupies an extremely substantial part of urban land, reflecting an important asset in capital investment. In Brazil, the relationship between housing and Urban Studies can usually be summed up by three main strands: the production of social housing resulting from state policies and programmes that increasingly reinforce public-private partnerships; the production of units by the private sector through medium to large enterprises; and the informal construction or occupation in empty, derelict or peripheral areas. The uneven combination of these strands coupled with unequal policies and inefficient distribution of infrastructure have significantly altered the relationships involved in the contemporary production of space, most significantly those occurring in contemporary urban voids of favelas and peripheral neighbourhoods.

2. A brief history of Rio de Janeiro's favelas and vacant land

According to Abreu (1994), the process of occupation of Rio de Janeiro's hills was encouraged by the government. In the end of the 19th century, for example, local authorities allowed the construction of wooden shacks in the vacant areas on the slopes of the Santo Antônio Hill to house the troops from the military campaigns known as Revolt of the Armada (1883-84) and as the Canudos War (1896-97). Simultaneously, the hygienist trend of that period contributed to the demolition of the tenements in the city centre, further increasing the number of poor people without housing. Many of the displaced residents went on to occupy the hills of Santo Antônio and Providência.

The role of private actors was also important to the consolidation of the favelas, especially landowners, who perpetuated the sale or illegal rent of land, most notably in the peripheries, leading to irregular occupations, which became the only viable alternative of housing to a large part of the population. As Holston (2013) puts it, unequal land access policies, such as the “Land Law” (Lei de Terras) [6] of 1850, were instrumental in ensuring that the lower classes occupied devalued areas.

This process was intensified after Rio de Janeiro's first large interventions towards urban modernization and renewal, such as the Pereira Passos projects in the early 1900s (see Vaz, 2002). These interventions were paired with legal evictions legitimized by hygienist trends and aesthetical improvements leading to the further destruction of popular tenements and other vast inhabited areas that were never rebuilt or modernized. The urban projects for the city centre would eventually be considered one of the key catalysts for the increasing of migration to the nearby hills and other vacant land. [7] Meanwhile, the newly restored central district saw the emergency of a high number of urban voids that would remain visible in the landscape for decades (Vaz & Silveira, 1999).

According to Borde (2004), Rio de Janeiro's urban voids are numerous and extremely diverse, varying from those occurring in public spaces to the in-between areas of the built environment. They also date back to different historical times and stem from specific economic, political and social transformations. More recently, many of the housing appropriations taking place in urban voids have been strongly connected to the sites and buildings which have been emptied due to deindustrialization. This phenomenon, which has taken over several large cities worldwide since the 1970s, had its height in Rio de Janeiro in the 1980-90s, generating new vacant land and buildings in former industrial and port areas. In the 2000s and 2010s, in a real estate speculation scenario, voids in strategic location were the main target for large urban projects aiming to reshape the city's global image and attract cultural tourists and investors (see Seldin, 2017). The vacant land and residual sites derived from deindustrialization in the favelas and peripheral neighbourhoods – most of which consist in former warehouses and factories – have remained as urban fringes, marked by self-construction and often improvised occupation, as is the case of the Portelinha Occupation in the Maré Complex.

The combination of self-construction and vacant land is key to understanding housing in Rio de Janeiro's favelas. For over 100 years, the spatial occupation of the poorer sectors of its population has been predominant on the hillsides, riverbanks and in peripheries – all marked by the scarcity of infrastructure and by relatively lower real estate value. Brazilian architect and scholar Ermínia Maricato (1982) claims that the absence of resources led most of the poor located in the large urban centres to self-construct not only their houses, but their collective buildings (i.e. churches and daycare centers) and public spaces (i.e. streets, squares). This self-construction favoured capitalist expansion because it consisted of unpaid labour, allowing the government to redirect resources to other sectors of society endowed with greater economic power. Still according to Maricato (1982), self-construction should be considered as a “possible architecture”, in a context of exclusion and exploitation of the working classes.

In other words, the favelas and their inhabitants have always been inserted in this city's urban reality, evolution and growth. This insertion has, however, been made by exclusion. By moving to the metropolis [8] in search of better living conditions, the poorer population dove into the capitalist system mainly as the cheap labour force determinant to generate its key surplus. For many, living in irregular and often unhealthy housing in the favelas has been the only means of survival and of adjustment to the system (Canedo, 2012; 2017). In fact, their existence may be better understood under the concept of tactics proposed by Michel de Certeau (1980) and Carlos Nelson F. dos Santos (1988). For De Certeau, tactics were the ordinary man's weapon who, faced with the problems of daily life, finds solutions to transform objects and spaces according to the possibilities they offer, subverting references and imposed norms, and opening cracks in the pre-established power relations. Additionally, Santos compares the city to a game with strict rules, in which the players' unpredictable actions lead to unforeseen results. In his game analogy, society rules represent the strategy while the unpredictable actions make up the tactics. In societies where the rules are usually created from a top-down perspective, situations that emerge in a bottom-up manner may allow life to go on. From this perspective, the self-construction of housing may certainly be perceived as survival tactics.

In the favelas, the absence of strict rules and the possibility to tactically shape space according to one's will is the feature that increases the sense of appropriation and belonging (see Jacques, 2005). As the Portelinha case suggests, self-constructed spaces allow for new urban interpretations and new social relations, constituting elements of potentiality rather than mere precariousness. Despite the poor conditions in which some constructions are built, their value is immense to a population segment that must deal with the inefficiency and inequality of policies and the scarcity of basic urban services.

3. Home, housing, subjectivity and territory

In a country and in a city where inequality [9] and housing deficit are so high, understanding the subjectivities behind the request for housing is essential. In this sense, the connection between the concepts of home and housing can be helpful to explain that providing people with a place to create roots is an essential right, which enables a sense of belonging to society as a larger entity.

A home, a construction for individuals, represents a place of their own in the world, one that must be cultivated and preserved. So much so that Bachelard (1978), in his phenomenological analysis of the home, explains its symbolic meaning by comparing it to a “nest” or “shell”.[10] The importance of housing cannot be understood without considering its connection to the concept of “home” itself because owning one is a guarantee that links may be established, not only with the built space but also with the surrounding neighbourhood, the community, the city and the country where it is located. In this sense, the spatial fixation through the habitat influences the strengthening of socio-cultural and territorial identities in a broader scale. In the case of Portelinha, for example, self-construction in the Timbau Hill meant that its inhabitants could still live in the Maré Complex after being displaced from its other favelas, thus, maintaining many of their existing ties to the broader local community.

At the heart of this discussion are the issues concerning the right to decent housing (Bonduki, 1999) and the right to the city (Lefebvre, 2001), and the understanding that a home goes beyond the idea of mere access to shelter (see Rybczynski, 1996). For Lefebvre (2001), social life is intensified in cities and urban centres. That is where exchanges take place and spaces are actually built for people to develop an active sense of citizenship and to experience everything that the city has to offer. That is why the right to housing needs to be understood beyond the physical dimension of architectural and urban projects, entering the symbolic sphere.

This right is also connected to the idea of people's claims for “living space”. This concept (see Lefebvre, 2007; Norberg-Shulz, 1984) implies the understanding of urban space as a social production of its inhabitants, who are constantly transforming it. The connection between people and places is mutual: both act by transforming each other, contributing to the creation of identities and to strengthening of the sense of belonging. From this perspective, urban space is primarily the place of relationships, not only social and cultural, but also between individuals and objects (Latour, 1991). In the self-built spaces, such as Brazilian favelas, this is even more evident. Not only because in many cases the urban space is defined and transformed by the dwellers on a daily basis, but also because the lack of participation of the State force the inhabitants to develop their own way of relating to their surrounding and neighbours.

Moreover, the right to housing is also connected to the fact that it constitutes the most important component of the built environment, occupying a considerable part of the urban land and attracting massive investments to the city (Vaz, 2002). When looking at housing solely from the point of view of the constructed elements, it is already a rich and varied object, which could be analysed individually or collectively, considering its architectural and aesthetic aspects, its internal divisions, its relationship with the landscape and so on. However, as a complex urban component, the way populations and authorities approach the issue of housing are traces of history, hence the true “centre of the space-society relationship", as Vaz points out:

We start from the premise that housing is historically defined according to the development of the socio-economic formations in which they manifest, and that there is a correspondence between the transformations that occur in these socio-economic formations and the transformations in housing itself - in their patterns, in the ways of producing them, of using them and of thinking them. It should be noted that we understand housing not only as shelter, a construction or an isolated element, but also as a component of the systems of spaces in which it is inserted, defining its complex use value (Vaz, 2002, p. 17-18).

Considering the need to understand housing as a complex system able to generate meanings, it is not enough to analyse the morphological and quantitative data of the Portelinha Occupation alone. We propose to show the importance of the “intramural favela” by briefly telling the history of its transformation of use – the process beyond its spatial characteristics, emphasizing its subjectivity, its potential for teaching planners and architects about the complex contemporary territories.

The connection between housing and territory in Portelinha is deep because this place embodies much more than the function of dwelling – it also incorporates culture, leisure and work, reflecting the reality of housing places in many self-constructed Brazilian favelas. To explain housing as territory, Ludmila Brandão (2002) takes on the reflections of Deleuze and Guattari about the “territory-home system”, showing the great proximity between these two concepts. She suggests thinking on house itself as a territory, since it transcends the building structure, the architectural set and the spatial configuration.

This relation seems interesting when considering the territory as a complex and contingent object – identitary, social, cultural and spatial, subject to diverse appropriations. The house, as well as the territory, represents a system of fixed objects and actions (Santos, 1997a; Haesbaert, 2010). It is endowed with meaning and with the particular expressions of those who construct it or who live in it. This is not only because its divisions and internal functions are always changing, but also because the definitions of how the house should be and where the house should be fixed can also be multiple, not following a pre-established notion.

This complexity of the territory is very evident through the Portelinha case. As, it will be shown, this place presents a plurality in terms of morphology and typology, corresponding to different layers added through time. The occupation can be referred to as an “intramural favela” – a smaller favela set located in a single land plot, within a larger favela complex. The “intramural favelas” are not exclusive to Maré. Many similar land plots have been emerging in the urban voids left behind by derelict factories and industrial infrastructure all over Rio de Janeiro and Brazil for the past couple of decades. They are frequently located in the fringes between the formal and the informal city, and are mixed with several occupations such as social and/or cultural activities, contributing to the emergence of true hybrid territories (Vaz and Seldin, 2016).

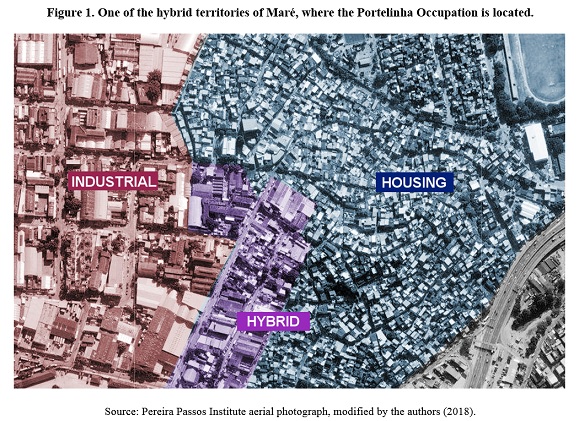

Hybrid territories result from a mix between the planned and the unplanned (Vaz, 2018). They can be perceived as a disorganized merge, very noticeable within the urban; a crash in the pattern of the morphology that often seems chaotic and improvised space (see figure 1). They mix the old and the new, the used and the unused, the designed and the spontaneous. The hybrid territories present new and intertwined land uses, new forms of appropriation, the recycling of old buildings as well as of leftover spaces. They incorporate both fixed and temporary structures and activities. In other words, they consist of new, ever-changing spatial patterns.

The hybridization of territories also goes beyond the physical, including what Nestor Canclini calls the “socio-cultural processes in which discreet structures and practices, that exist in a separate form are combined to generate new structures, objects and practices” (2008, p. 19). Much of the housing in favelas is built in phases, such as layers; and their physicality can reflect the stages of a family life: new stories and sections are added; uses are transformed; connections are built or destroyed. What was once a factory can turn into a cultural centre and then, into an improvised housing complex. Hybridization, as shown in Maré, means the impossibility to establish totalities in the contemporary city, and the need to recognize a tendency towards fragmentation and decentralization in social mobilization.

Cases of hybridism, such as the Portelinha Occupation in the Maré region, can also be explained by the concept of multi-territoriality, as proposed by Rogério Haesbaert (2010). This Brazilian geographer believes that, contrary to the late 20th century theories regarding the phenomenon of de-territorializing preached by many scholars, the 21st century will be marked by the emergence of multi-territories (p. 32). These territories are multiple, more complex and not characterized by continuity. He also highlights the urgency to examine the disparities and inequalities that cause contemporary accelerated transformations in space.

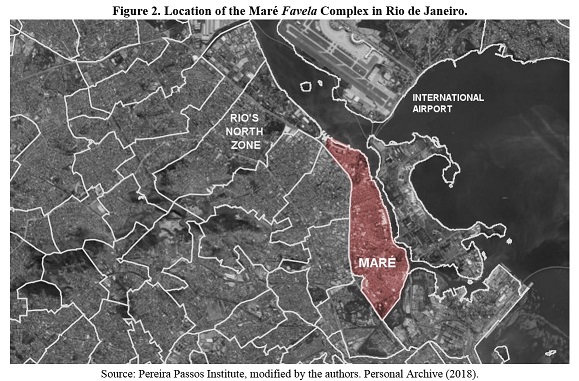

4. The Maré favela complex

The Maré Favela Complex (Complexo da Maré, in Portuguese), located on the northern part of Rio de Janeiro, is an ensemble made up of sixteen favelas, housing complexes and adjacent land plots, with approximately 130 thousand inhabitants in an area of almost 800 square kilometres [11]. In the last decades, Maré, as it is known, has been connected to strong images of violence on account of the constant conflicts between different drug trafficking gangs) and poverty, due to the poor social indicators and the high concentration of low-income population.

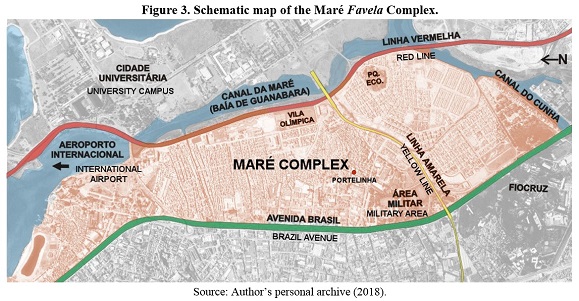

Although it has been considered an official administrative region and district by the local municipality since 1994, Maré is still widely perceived as a mere crossing area because it is located between two of the main local expressways, the Brazil Avenue (Avenida Brasil) and the Red Line (Linha Vermelha). It is also cut by a third one, the Yellow Line (Linha Amarela) (see figures 2 and 3).

In Maré, there has been a minor residential occupation since the Portuguese colonial period (prior to the 18th century), due to the existence of three local ports through which the production of sugar cane from nearby mills was exported. At this time, there was also the presence of small urban units formed by the colonies of local fishermen in the bucolic landscape of beaches and mangroves. However, it was only from the mid-20th century on, with the construction of the Brazil Avenue and the growing industrialization that the informal housing occupation in the region strengthened (Seldin, 2008).

Built on a landfill along the edges of the Guanabara Bay, the Brazil Avenue was inaugurated in 1946, incorporating new areas to the urban space, with the aim of constructing factories along the expressway. The whole region adjacent to the avenue had been formally destined to industrial activity, except for the existing military properties. However, this demarcation was respected, since the intensification of road transport in the country was only effectively strengthened in the 1950s, leading to the beginning of the occupation of empty lands by the favelas (Abreu, 2006). It is worth mentioning that, at this time, part of the new population was made up of the labour force used in the construction of the Avenue.

The increasing use of vehicles and the consequent intensification of the Avenue use would culminate in the proliferation of factories along its extension and in its surroundings, which ended up attracting a large population comprising mainly migrants from the country's North-eastern region. They tried to escape from severe droughts to seek a better life in the city, which was, then, the capital city of the country. The supply of employment in the industry sector and the need to live near the workplace led to the rapid occupation of this region.

Due to its mixed configuration of a marshy region with a small hill, the Maré Complex went through two basic processes of occupation: the construction of shacks in the dry and high regions; and the construction of stilts, initially installed in the marshy areas near the avenue and that, later, extended over the nearby Guanabara Bay. Hence, the occupation of each favela and community in Maré happened in a particular way, culminating in a great diversity of urban morphologies and architectural typologies.

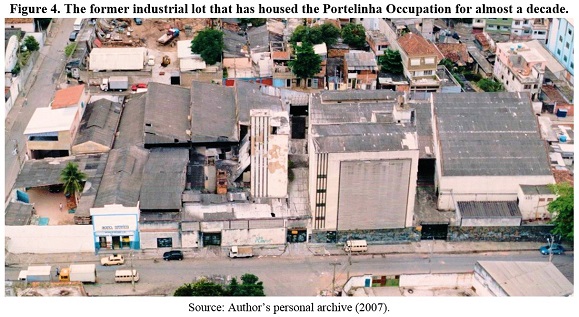

This morphological diversity was even more pronounced in an area adjacent to the Brazil Avenue, formerly belonging to the Bonsucesso neighbourhood. Here, until the 1980s, several factories, warehouses, and similar constructions were installed. They occupied large land plots and contained vast sheds, covered and uncovered patios, which eventually helped shape the local landscape.

This image of a dense industrial “periphery” started to change in the last thirty years, when the factories that had fuelled the local occupation began to close down and move to more profitable locations. This intense process of deindustrialization resulted in numerous urban voids. The area previously characterized by industrial structures was turned into a massive rundown, abandoned neighbourhood, filled with empty warehouses – an image that still prevails.

Nowadays, the Maré Favela Complex's urban space is easily distinguished by the clash between the predominantly residential plots, the two large sites belonging to the military police and the hybrid territory made up of its former industrial area (see figure 1), where overcrowded plots are mixed with abandoned ones and residential plots are mixed with industrial ones, leading to a multifaceted landscape.

5. The intramural favela: a disputed territory

Unlike the urban voids located around the historic centre of Rio de Janeiro, the industrial voids on the outskirts of the city were not targeted by public policies of urban renewal or even private capital-led interventions aimed at renewal processes and placemaking, remaining vacant and abandoned. In the case of Maré, as time went by, the old industrial sites were once again occupied somewhat irregularly, through mixed activities, that had nothing to do with the previous industrial ones, changing the urban space and the local relationships and thus consisting of what both Canclini (2008) and Vaz (2018) would define as hybrid territories.

Distinct types of spatial appropriations proliferated led by associative movements, cultural groups, service providers and even homeless people, who began to informally divide the land plots, building small sets of houses and shacks. By establishing a residence in the deactivated areas of factories, this population created a new type of appropriation: the “intramural favela” - a smaller-scale favela contained in a single land plot. This type of housing ensemble is not always clearly visible in the local landscape, because its growth occurs inside the warehouses and patios, hidden by the façades and walls of the former factories. It is, therefore, a new way of inhabiting the city, a type of collective dwelling improvisation generated as a response to the continually changing times, when nothing is what it seems, nothing is fixed, and ephemeral occupations prevail.

One of the most noticeable aspects of these new housing appropriations is that they rarely emerge in isolation. The modernist idea of a space being occupied by one singular main function no longer stands. Other types of temporary activities are also recurrent in the land plot, reflecting the post-modern society, were different functions are mixed together. This is the case, for instance, of warehouses where residential and informal services occupy the same space. An example is the large sheds, where shacks are built on top of pillars, while improvised payed parking spots occupy the ground floor. In this case, residence and an informal livelihood occupy the same space. The home is more than just residence: it is also the workplace.

This example shows that although the practices of production and reproduction of spaces within the favelas are increasingly inserted into the logic of the capitalist system (Abramo, 2009), the absence of an official and formal regulatory pattern leads to improvised everyday practices of negotiation that enable the consolidation of a more collective way of life. Abramo's study (2009) on the informality of the favelas ' real estate market and the capitalist practices carried out by their residents and former residents showed that, despite the strengthening of ties that emerged during the fights for property rights, individuals were more interested in working for their own benefit than for the collective. This conclusion is relevant because it stresses the several contemporary contexts in which slum dwellers relate to housing, proving that these occupations are heterogeneous and in constant transformation according to the different interests and powers at play.

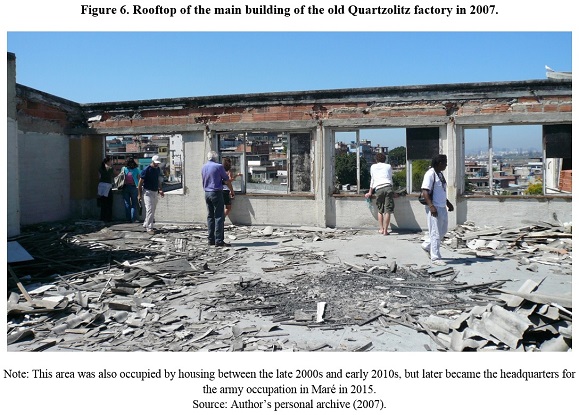

This heterogeneity is precisely what was observed during the field work carried out at the Portelinha Occupation. This example of an “intramural favela” that makes up a hybrid territory included negotiations between a great diversity of social actors in the site of a former paint factory in the Timbau Hill favela – the former Quartzolit factory, located in the Capitão Carlos street. Comprising a five-storey main administrative building, two large sheds and open courtyards (see figure 4), this space stands out due do having already sheltered housing, cultural, social and sports uses.

With the deactivation of the factory in the early 1990s, its legal owners found it very difficult to sell the property, due to the area's stigma of violence and heavy drug trafficking. Aware of the abandonment, the locals saw an opportunity for the graduate appropriation of the empty spaces in the mid-2000s: while some began to build new houses in the courtyards, others vandalized the main building, leading to a massive destruction of property (see Seldin, 2008).

Worried about the building decay after 15 years of abandonment, the Timbau Hill's resident association sought to avoid the more predatory occupations by contacting the landowners and the public authorities with a proposal to clean one of the courtyards in order to convert it into a sports court. This led to a period of articulation and negotiation between a wide range of different actors, which included residents, non-residents, leaders of cultural groups, NGOs, property owners, members of public agencies and even the drug trafficking gangs. The cleaning of the yard was carried out, and the sale of rubble and old iron was reversed for the benefit of the participants, who now felt even more entitled to use the empty spaces for their varied needs.[12]

In 2006, a capoeira [13] group, named Grupo de Capoeira Angola Ypiranga de Pastinha, occupied the ground floor of the main administrative building to ensure space for its cultural activities, preventing further destruction. After its installation, other cultural groups followed their lead (including musical, martial arts and educational collectives), recognized the potential of the building for the development of artistic activities in its ample halls. The artists had long suffered from the scarcity of spaces for their activities in the nearby favelas and decided to seek a peaceful alliance with the other occupants, which led to the creation of an alternative cultural facility in the area, attending to approximately 500 young Maré inhabitants, including 15 musical groups alone (Gonçalves, 2007). In 2007, the place became known as the Maré Popular Arts and Culture Centre.

The presence of multiple actors reinforces the premise that this place can be viewed as a disputed hybrid territory, not only physically but also socially and culturally (see Haesbert, 2010). This daily symbolic construction of housing, work, leisure, cultural options and social exchanges rarely happens without conflicts and the imposition of certain power structures and the Portelinha case is no exception. However, these conflicts should not be considered as a negative element. Learning to deal with them over years (and even decades) helped to strengthen the “insurgent citizenship” that is so characteristic of the Brazilian favelas, as suggested by Holston (2013). In the increasing absence of the state, the rules and hierarchies were defined by the occupants themselves.

The territorial conflicts in Portelinha also included the ones regarding the building owners and the state. In 2008, negotiations for an agreement between the landowners and the municipal government were unsuccessful. Despite the efforts of the community and cultural leaders involved, the slowness of the government, the massive bureaucracy and the lack of necessary resources for the continuous maintenance of the spaces led to a new occupation process of the courtyards and one of the large sheds by people who had been expelled from other nearby favelas in Maré. The construction of their houses inside the old factory plot, hidden by the walls, triggered the emergence of the “intramural favela” itself, later referred to as the Portelinha Occupation.

6. The Portelinha housing Occupation

The co-existence of the Portelinha Occupation and the Popular Arts and Culture Centre turned this site into a hidden, little-known hybrid space for most of the late 2000s. All of the parties involved perceived this location as their own, but with diverse approaches. To each group, the place meant something different. The new inhabitants saw the empty patios as an opportunity to assert their right to housing and to build their houses from scratch in an improvised manner, turning their dreams of having new dwelling spaces into reality. The constructions did not follow specific patterns or urban laws and became a large group of homes, squeezed together in the available land. Some of the original roofs of the old factory were torn down and the vacant space – a classic example of the industrial urban voids conceptualized by Borde (2004) – were divided according to the hierarchy of the occupants. These new dwellers had various backgrounds and most came from other favelas within the Maré Complex, following displacement or violent eviction from drug trafficking gangs. [14] For them, Portelinha meant a second chance to establish roots near their old communities.

The cultural groups needed the space to get together and collectively create art. Even though, some members saw the need to temporarily squat in the building in order to guarantee that others would not take over their space, most of them had homes of their own in other parts of the favela complex. For them, the old factory was a place for the act of creation, for creativity, for the production of something immaterial.

The local associations and social mediators understood the factory lot on a broader, urban scale, as a part of the neighbourhood in need of help, either by degradation or by conflict. This approach was more closely related to the idea of a community being able to enjoy a space full of potential together, giving something back to the present construction of the collective local memory.

The actions, networks and relationships created by the aforementioned groups have contributed to transform the existing dynamics of the favela, leading to new local experiences. The continuous construction and reconstruction of the Portelinha Occupation as a territory is, therefore, a process of exchange, in which space is used in different and multiple ways, serving the purpose of unifying rather than fragmenting. The actions of dwelling, working, leisure and circulation are activities not necessarily set apart in this place. They co-exist within space, they are ever-changing, hybrid and they reflect different spatial patterns of spatial occupation.

This case study shows how one place can mean different things to different people and how housing can take on different interpretations depending on its context. Inside Portelinha, the new self-built constructions imply a broader range of uses that surpass the traditional dwelling activities (sleeping, cooking, bathing ). They are also places where some people work, and where others create and play.

Considering this multiplicity of uses, it becomes clear that housing occupations in favelas should be understood as proper urban tools for intervention and transformation of the built space. They can lead to either change or preservation and they reflect a means of resistance to an imposed urban planning model. Self-constructed housing options can even be thought as innovative when considering the different ways of appropriating pre-existing spaces (Canedo and Andrade, 2018). In other words, favelas are filled with people who are so used to improvising that they see the potential to “think outside the box” and create something entirely new to face urban disparities, like a favela hidden by old walls.

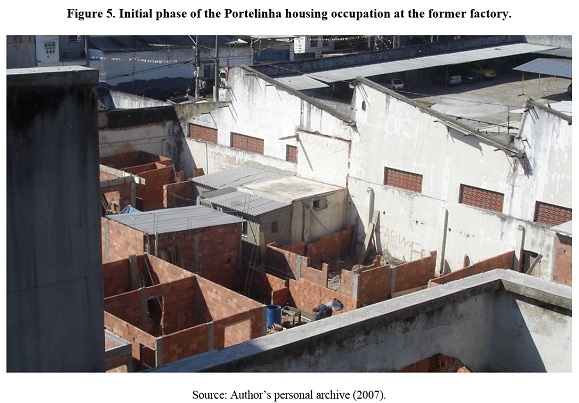

On the other hand, this creativity does not come without a price. While the idea of an “intramural favela” is innovative, the actual living conditions in Portelinha can be somewhat precarious. The houses vary in number of floors and materials not following the local codes. In addition, almost all of them lack exterior coating and finishes, leaving the brick structure exposed. They are mostly all glued together with very little room for ventilation, natural lighting and circulation (see figures 5 and 6). Since they are irregularly and illegally constructed, some of them lack proper connection to the sewage system and water provision can face some problems. Other basic infrastructure, such as electricity, is also illegally appropriated. Moreover, occupants face the uncertainty of not having the property rights to the land plot.

The articulation between different groups at the former Quartzolit factory lasted until approximately 2013. Fearing an eviction due to the growing housing speculation in the city, the occupants began to organize themselves more systematically, promoting meetings in partnership with non-governmental organizations and university institutions (such as the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro - UFRJ) to better understand their legal situation and their rights regarding the property. The Portelinha residential occupation and its approximately 500 inhabitants (Cunha, 2015) benefited from these rights, so eventually, most of the fixed cultural groups, including the capoeira one, left the building as conflicts intensified and the mediations between the different actors became more difficult.

In 2015, the Brazilian army occupied the main building of the old factory as part of a larger security policy of the city. During that time, local cultural groups, such as the newly created carnival band “Magia do Samba”, organized temporary events at the place, which included dance and food parties. One of them, intitled “Charme in a War Zone”[15] represented a clear silent resistance to the often-brutal military presence and included improvised debates surrounding the favela and the city's current political and social situation (see Cunha, 2015). Many inhabitants believed that this presence had more to do with controlling the city's violent image before the 2016 Olympic Games [16] than an actual preoccupation with the well-being of the locals. Considering all the different actors involved in this site for the past decade, it is interesting to stress the level of improvisation of the inhabitants to mediate their conflicts and to deal with each other as part of their daily lives. This mediation is also similar to the tactics proposed by De Certeau (1980) as it happens little by little, according to the given opportunities and the possible occasions that arise from the changing local power struggles in this disputed territory.

Today the patios are fully occupied by houses, but almost a decade after the beginning of the appropriation of this much-disputed site, the situation of the dwellers is still uncertain when it comes to legal issues. What is certain is that their trajectory reflects an increasingly common process in the contemporary Brazilian peripheries, and by extent the Latin American ones: the creation of temporary and hybrid territories and the rise of favelas within favelas – filled with mixed and transitory uses. Portelinha also reflects a meeting of the abandonment of old industrial territories with the need of the population to fix their roots in a place that allows them to build individual and collective memories in their own way. Moreover, this case, along with many other housing occupations spread through Rio de Janeiro, relates to the people's right to shelter, their right to strengthen their ties with the urban space and the fight for the right to the city, reflecting Lefebvre's theory (2001).

Understanding the Portelinha case as a multi, hybrid and disputed territory and connecting it to the struggle of its inhabitants to their right to the city is essential, since it shows that architects and planners must review their professional approaches in contexts marked by great social disparities, such as the Brazilian and Latin American ones. Both the practical and scientific sides of their field must keep going beyond the formal and functional issues that have dominated it for over a century to focus on the aspects that are not necessarily materialized in space; those connected with experiences, sensations and feelings of belonging. According to Luciana Andrade (2002), human and social history are inseparable parts of space, which hinders an outlook solely considering the urban form, the morphologic perspective. Space can contribute (or not) to the development of certain practices and appropriations and planning professionals must always bear this in mind. This approach would be similar to what Jacques (2005) calls “poetic urbanism”, connecting the body of the city to the body of the individual through experiences:

The architect and planner should never - in order not to design spectacular or disembodied spaces - forget to physically or even lovingly, I would say, relate to the city itself, their object. The distance, or detachment, between subject and object, between professional practice and physical-living experience of the city, is disastrous because it eliminates what urban space has that is the most urban, which would be precisely its human character, or worse, it eliminates what is the most human about man: his own body (Jacques, 2005, p. 24).

This renewed professional approach that embraces and works with hybrid territories such as Portelinha has much to do with understanding that the physical urban space, no matter how precarious, carries a lot of symbolic meaning (see Santos, 1997b; Lefebvre, 2001). The physical environment interacts with the social one, influencing and transforming its dynamics and vice-versa, in a continual and dialectic process that will never be fully apprehended by architects, urbanists and planners. What these professionals must learn how is to incorporate the symbolic into their practices, in order to deal with these new urban phenomena, such as the “intramural favelas”, dignifying them, instead of trying to impose an external social living experience through a pre-determined way of designing and planning. It is imperative for them to understand that the physical structure of space emerges as a means of support to pre-existing and mutating social dynamics. The physical structure must be constantly adjusted and flexible, so that it can also transform according to the community that uses it. To sum up, it is necessary to pair technical knowledge with living experience, incorporating in a more incisive way the daily lives of people in the elaboration of the urban projects, designs and plans.

7. Final considerations

The intention of this article was to study new ways of urban expansion through housing in the contemporary informal city, going beyond the design aspect and taking into account the subjectivity of housing as part of the territory around which social relationships are built.

The case of Portelinha in Rio de Janeiro shows how even an abandoned and degraded space, located in an extremely undervalued urban area can possess great worth for many people, especially in terms of the possibility to gain the right to belong to the city, to be seen as a place to build or rebuild life within a specific community. It also shows how urban voids, characteristic of the deindustrialization phenomena, are appropriated in this specific context of social, economic and cultural inequalities. This study shows that the worldwide trend of spectacular appropriation of space through placemaking strategies (see Seldin, 2017) does not occur in the contemporary city as a whole, in an even manner. Policies and strategies focusing on the cultural renewal of vacant sites can be very unevenly distributed through present-day cities, favouring solely the areas that are attractive to the development of real estate markets and further deepening pre-existing disparities. In Rio de Janeiro, the unequal policies end up reinforcing the precariousness of certain areas. In these areas, people are forced to improvise, self-build and create new uses that subvert the local zoning laws as a way to guarantee their right to housing (and culture). In doing so, they create new forms of territories, which are multiple, hybrid and disputed in accordance to the framework proposed by Canclini (2008), Haesbaert (2010) and Vaz (2018). These territories do not fit into the pre-established patterns with which architects and planners are used to work, so they must learn to deal with them, seeing their potential and not only criticizing their negative aspects.

Dealing with informal settlements and spaces that have been built in layers without the technical expertise of architects and urbanists through decades, hosting temporary and ephemeral uses, is a challenge. It surpasses the aspects of typology and morphology because it also entails in proposing betterments to the ampler urban infrastructure and mobility, requiring solutions on how to access work, leisure and cultural places. The challenge also lies in dealing with a complex and negative broader political, economic and cultural context. This research was conducted through a long period of time that saw major corruption scandals involving big building and developing firms and considerable changes in Brazilian government, redirecting the priority of federal policies. After elected president Dilma Rousseff's impeachment in 2015, a number of measures have been taken to accentuate the capitalist and neoliberal agendas in the Brazilian cities.

In Rio de Janeiro, in particular, the disparities have become even more ramping after the Olympic Games and megaevents, when many resources were redirected to raise the local urban image by building spectacular facilities in strategic, central and more affluent neighbourhoods. After massive expenditure, many construction firms' leaders and locally elected representatives are currently in prison or under investigation for intricate money laundering schemes that left the broader state of Rio de Janeiro bankrupt. This has significant consequences to the local social movements, especially the ones linked to the fight for housing, which is the focus of this study.

The economic crisis and political instability have worsened in recent years and this fact has tremendous impacts on the most vulnerable population of the city. Considering this current context, the very existence of Portelinha configures a resistance to the many processes of real estate valuation that keep displacing the poorer classes to the more inhospitable city regions with less urban infrastructure and services. This resistance is not only perceived through the social fight for housing itself, but also through the construction of alternative urban dynamics, alternative relationships between housing spaces and living spaces, alternative multi-territories and the reconstruction of a new notion of citizenship, the “insurgent citizenship” proposed by Holston (2013).

In conclusion, in this post-modern context of inequalities observed in contemporary Rio de Janeiro, plagued by complexity and difficult territorial conflicts, new and differentiated forms of urban growth and expansion take place, as creative and challenging solutions that need to be better understood by professionals, so that their priorities can be readjusted, and urban planning may move towards a fairer city.

References

Abramo, P. (2009) (Ed.) Favela e Mercado Informal: A Nova Porta de Entrada dos Pobres nas Cidades Brasileiras , Porto Alegre: ANTAC. [ Links ]

Abreu, M. (1994) “Reconstruindo uma História Esquecida: Origem e Expansão Inicial das Favelas do Rio de Janeiro”, Espaço e Debates - Revista de Estudos Regionais e Urbanos, XIV, n. 37, 34-46.

______ (2006) Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro: IPP. [ Links ]

Andrade, L.S. (2002) A Constituição de Espaços Públicos em Favelas, Rio de Janeiro: Faculdade de Geografia - UFRJ (Doctoral Dissertation) [ Links ]

Bachelard, G. (1978) La Poétique de l'Espace, São Paulo: Abril Cultural. [ Links ]

Bonduki, N.G. (1999) “Do cortiço a moradia digna: uma questão de vontade política”, Urbs, São Paulo, n. 11.

Borde, A.L.P. (2004) “Vazios urbanos: Avaliação Histórica e Perspectivas Contemporâneas”, in M.C.S. Leme, R. Cymbalista (Eds.) 1990 a 2008: Dez Seminários de História da Cidade e do Urbanismo, v. 8, n. 5.

Brandão, L. (2002) A Casa Subjetiva, São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva. [ Links ]

Canclini, N.G. (2008) Culturas Híbridas: Estratégias para Entrar e Sair da Modernidade. São Paulo: EDUSP. [ Links ]

Canedo, J. (2012) Intervenções Urbanas em Favelas - O Arquiteto no Processo Coletivo de Construção e Transformação das Cidades , Rio de Janeiro: PROURB/FAU/UFRJ (Master Thesis) [ Links ]

______ (2017) Direito a Outra Cidade: Ocupações e Favelas Como Táticas de Resistência e Transformação , Rio de Janeiro: PROURB/ FAU/ UFRJ (Doctoral Dissertation) [ Links ]

Canedo, J., Andrade, L.S. (2018) “Espaços de Experimentação: a Favela Indiana Como Reflexão para Práticas de Transformação do Espaço Urbano” in L.F. Vaz, C. Seldin (Eds.) Culturas e Resistências na Cidade, Rio de Janeiro: Rio Books, 193-215.

Certeau, M. (1980) L'Invention du Quotidien. 1. Arts de Faire, Petrópolis: Editora Vozes. [ Links ]

Cunha, R.J. (2015) “Charme em Zona de Guerra da Maré”, Quartzolit. Jornal da ASFUNRIO, jul. Available at: http://asfunrio.org.br/editorias2015/JornalOnline/mkt2015-010-01.htm. Accessed on 13 December 2018.

Davis, M. (2006) Planet Slum, São Paulo: Boitempo. [ Links ]

Gonçalves, M. (2007) “De Fábrica Abandonada a Centro Cultural”, Jornal O Globo, Zona Norte, 3 jun.

Jacques, P.B. (2005) Errâncias Urbanas: A Arte de Andar Pela Cidade. Caminhos Alternativos à Espetacularização das Cidades , Porto Alegre: ARQTEXTO (UFRGS) [ Links ]

Haesbaert, R. (2010) O Mito da Desterritorialização: Do Fim dos Territórios' à Multiterritorialidade , Rio de Janeiro: Ed. Bertrand. [ Links ]

Holston, J. (2013) Cidadania Insurgente: Disjunções da Democracia e da Modernidade no Brasil , São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (1991) Nous n'Avons Jamais Été Modernes. Essai d'Anthropologie Symétrique. Paris: La Découverte. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. (2001) The Right to the City, São Paulo: Centauro. [ Links ]

__________ (2007) The Production of Space, Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Maricato, E. (1982) “Autoconstrução, a Arquitetura Possível”, in E. Maricato (Ed.) A Produção Capitalista da Casa (e da Cidade) no Brasil Industrial, São Paulo: Editora Alfa-Ômega, 71-93.

Norberg-Schulz, C. (1984) Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. New York: Rizzoli. [ Links ]

Rybczynski, W. (1996) Casa: Pequena História de uma Ideia, Rio de Janeiro: Editora Record. [ Links ]

Santos, C.N.F. (1988) A Cidade Como um Jogo de Cartas, São Paulo: FINEP/IBAM. [ Links ]

Santos, M. (1997a) A Natureza do Espaço. Técnica e Tempo. Razão e emoção, São Paulo: Hucitec. [ Links ]

________ (1997b) Metamorfoses do Espaço Habitado, São Paulo: Hucitec. [ Links ]

Seldin, C. (2008) As Ações Culturais e o Espaço Urbano: o Caso do Complexo da Maré no Rio de Janeiro , Rio de Janeiro: PROURB/FAU-UFRJ (Master Thesis) [ Links ]

________ (2017) Imagens Urbanas e Resistências: Das Capitais de Cultura às Cidades Criativas . Rio de Janeiro: Rio Books. [ Links ]

Silva, M.L.P. (2001) Olhando a História para Entender o Que é Realmente Novo no Presente , Salvador: Fórum Habitar 2000. [ Links ]

Vaz, L.F. (2002) Modernidade e Moradia; Habitação Coletiva no Rio de Janeiro - Séculos XIX e XX , Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras. [ Links ]

________ (2018) “A Cultura e o Território: Uma Reflexão sobre os Espaços Opacos Cariocas” in L.F. Vaz, C. Seldin (Eds.) Culturas e Resistências na Cidade, Rio de Janeiro: Rio Books, 25-41.

Vaz, L.F., Seldin, C. (2016) “From the Precarious to the Hybrid: The Case of the Maré Complex in Rio de Janeiro”, in K. Kosmala, M. Imas (Eds.) Precarious Spaces: The Arts, Social and Organizational Change, Bristol/Chicago: Intellect, 37-59.

Vaz, L.F., Silveira, C.B. (1999) “Áreas Centrais, Projetos Urbanísticos e Vazios Urbanos”, Revista Território, IV, n. 7.

Received: 12-04-2018; Accepted: 28-12-2018.

NOTES

[3] The term favela refers to the Brazilian version of slums, sprawled on either flat land or climbing up the hillsides. They usually replace the former green areas and hills with a morphology of densely packed constructions, often shacks of low-quality infrastructure, where the poorest population inhabits (Vaz & Seldin, 2016).

[4] Data taken from the João Pinheiro Foundation website. Available at: http://www.fjp.mg.gov.br. Accessed on 11 December 2018.

[5] Idem.

[6] Law n. 601 of 18 September 1850 was created to organize records of land donated from the colonial period and to legalize the lands occupied without authorization, later recognizing the so-called vacant lands as property of the State.

[7] It is important to highlight that the increase in migration from other states of Brazil (especially those located in the Northeastern region) to Rio de Janeiro also played an important role in the growth and consolidation of the local favelas throughout the 20th century.

[8] Rio de Janeiro is Brazil's second largest city in population and was the country's capital until 1960 – facts that attracted a large number of migrants from other cities.

[9] According to Oxfam, the reduction of the gap in income inequalities in Brazil stopped in 2017 after 15 years and the country became the 9th most unequal nation of the world. It registered 15 million poor people in the same year, with a daily income of US$ 1,90. That number was 1,7 million higher than in 2015. Information available at: https://gazetaweb.globo.com/portal/noticia/2018/11/_65216.php. Accessed on: December 12th, 2018.

[10] When speaking of the "nest", Bachelard (1978) evokes images of simplicity, resting, retiring in tranquility and of recollection from the rest of the world. The house is presented as a comfort place and also a refuge. When speaking of the "shell", the author emphasizes the role of the solid walls, which protect and allow closure, the preservation of intimacy, protection and security. When comparing the house with such elements, Bachelard emphasizes the natural character of dwelling, placing it as a natural necessity of human beings. The house is people's nest and shell in the world, a place that shelters both physically and mentally, allowing and nurturing the development of imagination and dreams.

[11] According to the 2010 demographic census and the Pereira Passos Institute.

[12] Information taken from interviews to the leaders of two groups who occupied the place in 2007 and 2008.

[13] Capoeira is a cultural practice that mixes sports, fighting, game, music and dance. It started in Brazil and has spread worldwide.

[14] Information taken from the observation during the field research and from interviews with the leaders of two groups who occupied the site in 2007 and 2008.

[15] Charme (“charm” in English) is a Brazilian rhythm that is a strand of R&B. It incorporates elements of the hip hop movement adapted to the Rio de Janeiro scene.

[16] Rio de Janeiro was the host of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and of the 2016 Olympic Games. The Maré Complex was held as a strategic territory regarding the city's violent image not only because of its frequent shootings, but because of its location – close to the international airport, meaning that many of the visitors would have to pass by it once arriving from abroad.