At first, it was just putting K and pop together

K-pop, as a musical (sub)genre, can be interpreted as being a transnational artistic production that, in turn, has as its main objective the engagement of audiences, at different levels of industrially created global imagination (Yoon, 2018). Thinking about Appadurai’s (1996) considerations, we can state that this musical genre is guided by a constellation of permanent tensions, between those that are the processes of cultural homogenisation and the processes of heterogeneity (Regev, 2013) and authenticity. Then, based on this assumption, we can say that K-pop is also assumed as a media, cultural and social phenomenon.

In fact, the growth and evolution of K-pop since the 1990s is intrinsically related to the dissemination of pop idols, an aspect that reached a different scale with the globalization of the group BTS. These bangtang boys epitomise the numerous processes of global mediation at the level of the South Korean recording industry, but also regarding digital and non-digital media. Dissemination is perhaps the industry’s main concern, hence it is personalised, multifaceted and global, something visible in the millions of views that music videos get within hours of their release. In fact, a strategy is adopted for each country and, in this sense, for the Portuguese context - being a small country, in the scale of the projection of K-pop bands - the use of and investment in digital media is essential1 (Galloway, 2020).

K-pop is much more than a musical genre demarcated by a geographical context. We ventured to say that, due to the millions of followers, the consumption of merchandising, the dissemination and consumption of other South Korean cultural contents, it can be seen as a revealing element of contemporaneity all over the world, in the sense that it increasingly emphasizes the importance of world music (Shahriari, 2018). Although this genre emerged in South Korea, it is not intended for exclusive consumption by the local population, in fact, it is a genre that is mainly produced for non-Koreans (Yoon, 2018). The construction of idols is paradigmatic. Perhaps it was due to this phenomenon that we felt the need to carry out this work, since memorabilia gravitates around a personal, aesthetic and performative identification of the self with that idol(s) and with that culture, that is, a dialectical relationship is created that attributes meaning to objects (Guerra & Quintela, 2020). In fact, the authors even state that popular music has been deeply associated with practices of preservation of memorabilia and increase of personal archives/collections, however, little academic attention has been paid to these practices and to the objects themselves (Bennett & Rogers, 2016), making it pertinent to fill this gap, starting studies that focus on these cultural expressions that, in their essence, compose modern archives: photographs, record covers, concert tickets, posters, newspapers, among others. Compared to what the authors denote for the field of fanzines and independent publications, with regard to K-pop, we identify the existence of new notions of archive, heritage and memory (Alberto & Guerra, 2019), linked to contemporaneity and that, in fact, demonstrate and reveal hybrid identities. Thus, what starts as a personal desire, quickly becomes a need to belong to a broad movement, the fandom (Choi & Roald, 2015). Groups are a majority in the face of solo artists within K-pop and, whether those emerging or those already established within the music industry, all fit an aesthetic, industrially produced and created standard. Groups such as BTS2, GOT73, EXO4, BIG BANG5, but also women's groups such as BLACKPINK6, Red Velvet7 or Girl Generation8, gravitate around the same image. They are young, physically attractive and artistically multifaceted, as they can sing, dance and act. Another very important aspect is related to the fact that the groups are homogeneous, there are no mixed groups - or at least with the same frequency as male or female groups -, only boy bands or girl bands. To this aesthetic concern is added the musical concern, for the songs meet Americanised industrial demands. Thus, in addition to the songs being catchy, they must be conducive to the creation of custom choreography which, in turn, is rehearsed until synchronisation and perfection is achieved (Lie & Inghyu, 2014). Furthermore, for both male and female groups, utopian aesthetic imperatives persist which dictate appearances and tastes, for example to lose weight, to be beautiful, to have good physical condition, hair, skin, the use of make-up, absence of tattoos or piercings, among others. Although the fandom is homosocial, there are strong gender ideologies present in the K-pop industry (Jung, 2010). In fact, it is these paradigms that mark the K-pop nietizens (citizens of the internet) and that exert a constant pressure towards the members of the groups, creating a hyper-enhanced self-consciousness about their appearance, promoting ideas of integration into specific standards of beauty. Thus, we are facing mass beauty standards, while we can frame them in a duality between progressive/conservative (Laurie, 2016).

However, there is a hidden face of this entertainment industry. This industry does not follow the same procedures as the American industry, for example. Most of the time, artists are not discovered singing on platforms like YouTube, on the contrary. The idols are subject to systematic and hard training, often enrolled in academies (Han, 2015) by their parents and live the life of a trainee from an early age. Being a trainee means living, rehearsing and performing in a group. They all have regular dance classes as well as singing lessons, and some learn rap to set themselves apart from the rest. From an early age, they create YouTube channels to post videos that meet a marketing strategy that encourages the creation of a fandom. They must also maintain their physical fitness, while also excelling in facial expressions while performing (Yoon, 2018). When we are faced with young idols like those who make up the aforementioned bands, we enter another level of rigidity and discipline, just take as an example the prohibition made by labels in terms of love relationships. Many do it in secret and if they are discovered they can even be expelled from the label. The aim is to make fans imagine that their idol could be their love partner.

Thus, this attraction that is created around K-pop and its idols leads us to other issues, namely to the physical field. This article does not intend to approach K-pop from the point of view of industry, dissemination, nor performance. The focus will be on the audiences. Even more specifically, we intend to analyse the collection of memorabilia, since the number of groups in social networks of sale/exchange of merchandising has increased exponentially, especially in Portugal. These labels, such as Big Hit or YG, can be seen as gatekeepers that systematically explore and maintain an international strategy of exporting an imaginary and a high-quality model, but at relatively low prices (Sun, 2020). It is the industry of customisation and embodiment, but also the industry of global imaginaries. This is where the innovative nature of this article lies. Until now there has not been a focus on the material issue of K-pop, on memorabilia, not having also been made an investment in the approach of this dimension and its interface with the transnational experience that K-pop allows, much less in Portugal. In this way, throughout this article we will approach the question of consumptions, but also the connection of these with the emergence of a fan identity, materialized in the objects from the other side of the world. In parallel, images of memorabilia of the Portuguese fandom will be presented, following a qualitative methodology, based on content analysis of items related to the universe of K-pop (Pink, 2020), referring to seven young K-pop fans, aged between 20 and 28 years, following and adopting the methodological procedures proposed by Sarah Pink, at the level of sensory ethnographies. It should also be noted that all the photographs presented in this article were provided by the girls contacted. For this purpose, contact was established through social networks and based on their participation in a closed group of sale/exchange of K-pop merchandising. The first ten publications in the group were contacted, seven of which answered.

Haru haru. One day after another in the K-pop industry

South Korea is undoubtedly one of the main countries responsible for the distribution of global popular music, hence it is important to look at the impacts of such distribution in countries like Portugal and in the most different spheres because, even though it is a small country, fandom has grown substantially. However, the South Korean music industry has not always been directed towards the world. On the contrary. South Korean popular music included ballads and foreign content that was imported from Japan or the American colonies during the period of military invasions (Oh & Lee, 2014). In the early days of the industry, the kayo (pop music) music genre was associated with a set of deeply stigmatising stereotypes, in the sense that lovers of the genre were seen as gangsters. In fact, this stigmatisation has only changed more recently, as aesthetic choices such as tattoos were frowned upon, as was the case with the artist Jay Park9, for example. As Oh & Lee (2014) enunciate, it was in the 1990s that the first male K-pop group emerged, Sobangcha10 and then the group Seo Taiji and the Boys11. These two groups have largely contributed to overcoming these negative representations associated with pop music, and with them came changes on the part of the public, with singers now being seen as sophisticated and professional stars who use their creativity for the benefit of the public and the industry. Indeed, “while Seo Taiji and the Boys are not responsible for the development of K-pop as a genre, their success proved that a fusion of western music and Korean sounds resonated with a youth that was trying to find its own place in an increasingly globalized world.” (Oliver, 2020, p. 21). Other authors such as Kim (2011) explain the popularisation of the phenomenon in China in the mid-1990s, with groups such as H.O.T12 or solo artists such as BoA13.

Based on the contributions of Oliver (2020), K-pop can be understood as a product of globalization and, as such, it can be seen as a cultural product that is made to please the masses, always maintaining its local character and specificities (Regev, 2013). Based on this premise, this musical genre can be understood as a mix between what is contemporary pop, hip-hop and also - and an element that demarcates the transnational character - we have present quite often, infusions of the English language. In this sense, Oh D.C (2017) states that K-pop is a hybrid format marked by mugukjeok qualities, i.e., qualities that make up for the absence of a nationalistic character, an aspect that largely contributes to its expansion and commercialisation. Another emerging issue concerning K-pop and its consumption is related to the fact that this music genre is future and youth culture oriented (Baker et al, 2016), as attested by the type of performances that are performed, especially by male K-pop groups, where sensuality (Laurie, 2016), but also romance and shyness prevail. In what concerns female groups, the captivation of the audience goes through beauty and shyness, or rather, the captivation is based on a cuteness logic (Han, 2016; Kim, 2011) and on the advent of feminist and empowerment discourses and rhetoric (McRobbie, 2009; Gill, 2016). Something that exacerbates these characteristics is fashion, namely different coloured hair, hairstyles, accessories and clothes, which are part of the K-pop lexicon and, as such, are imperative elements in the groups' visual communication strategies and a constant in memorabilia items. Thus, these elements combined, make K-pop distance itself from the American legacy (Urbano et al, 2020), being the same strongly linked to the creative industry, in the way Flew (2017) tells us, in the sense that they are the driving force behind the creativity of the groups, while these industries are the main causes of the intense relationships between fandom and idols (Sun, 2020).

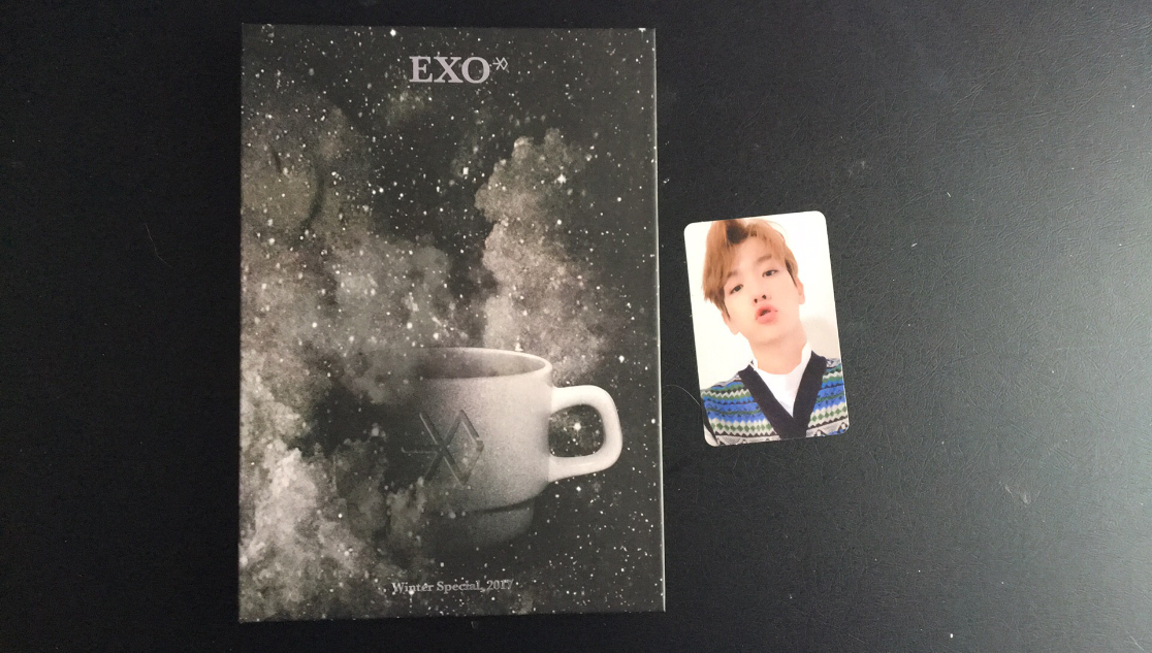

At the same time, the interactions with fans are essential for the maintenance of the industry, as well as for the genre to be successful, as is the appanage of the history of cultural theory (Duffett, 2015), whose practices and activities of fans are considered essential for the industry to work. In this way, there are several vlogs, privileged appearances in talk shows and social networks (although many of them are managed by managers), contributing to the loyalty of fans, recognizing and classifying them as admirers, as connoisseurs of a particular theme/artist, collectors and, ultimately, they are placed in a relentless identity search that aims to identify with a particular style (Duffett, 2015, 2013). So, unlike those that are the American idols (Urbano et. al, 2020), for example, where a difference is marked between the artist and the audience, K-pop idols find their strength here. As Oliver (2020) points out, there are several ways for fans to interact with their idols, be it through involvement in the choreographies, learning the lyrics and, of course, acquiring memorabilia such as CDs, photocards, calendars, lightsticks or other differentiated products such as keyrings, calendars (see Figure 1), posters (see Figure 2) or soft toys. Concomitantly, we must alert to the fact that we are not talking exclusively about fangirls, as is usual for American boy bands because, in the case of K-pop, there is a considerable number of fanboys who make reactions to the music videos on their YouTube channels14.

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 2 Poster of K-pop idol Baekhyun, from the album Delight, the Chemestry version, from Beatriz Faria

When we spoke earlier that K-pop is oriented towards youth cultures, it is important to highlight the fact that more recently there are a considerable number of older fans, i.e., mothers and fathers who follow the tastes of their children and eventually end up surrendering to the K-pop industry (Lie, 2012). As Yoon (2018) states in his work Global Imagination of K-pop, idols must stay true to the image of an accessible star, largely contrasting with Western idols. Thus, the previously stated characteristics, such as beauty, talent and attractiveness, are attributes supported by an investment in the aesthetics of K-pop albums (among others), appealing to the masses (Oliver, 2020). Although numerous studies consider that the purchase of CDs is obsolete, for K-pop the exact opposite is true. The CD remains as a strong attractive and collectible symbol, and cannot be replaced, because its commercial exchange value would no longer be in question (Choi, 2014). In parallel, the CD and other collectibles, as physical objects, can also be understood as a strong symbolism of nostalgic feelings, as well as of fundamental imaginaries for, in the medium and long term, us to understand the ways in which the production and experience of South Korean pop music has been established with the fans (Guerra & Alberto, 2021). Furthermore, part of the success of K-pop albums is related to a strong investment in restructuring marketing techniques and engagement with fans, i.e., products are designed and created after listening to fans’ tastes. As Patryk Galuszka (2014) highlights, the relationship between fans and producers has been widely studied for these reasons, i.e., the fact that there is a dual and ambivalent relationship, but also one of interdependence; however, few studies have looked at the products that are born from this troubled relationship, nor have they detailed the symbologies for fans. Once again Choi (2014) offers us important inputs, in the sense that she states that the Korean music industry has moved from an exchange perspective to a relationship perspective, with an emphasis on the (co)creation of value. Thinking about the memorabilia previously enunciated, there is in parallel a strong investment in the creation of varied, highly collectible products (Alberto & Guerra, 2019).

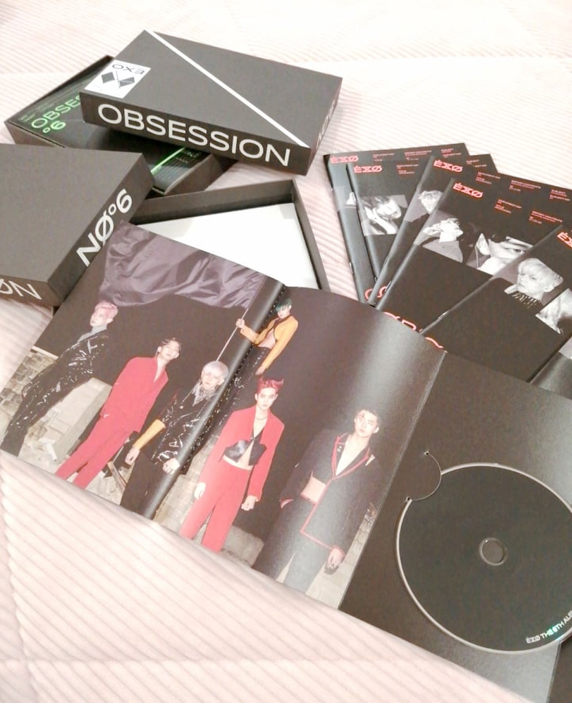

K-pop albums are produced in a varied way, however, four categories seem to emerge: i) the production of the same album, but with different packaging and with exclusive contents; ii) a re-release of an album with additional songs; iii) a separate album in another language, such as English, thus meeting the genre’s claim as being a universal sound, fitting within a universal pop logic (Urbano et al, 2020; Regev, 2013); iv) finally, the re-releases. Some examples of these categories can be given, for example the BTS album MOTS: Persona was made in several versions, with each package having a variation in colour, i.e., it was made in four shades of pink. Or also the albums of Monsta X18 and of WayV19, which were released with English-only tracks, in order to promote their American debut. These types of productions are highly appealing to collectors and fans, mainly because they can enjoy multiple versions and variable contents. Furthermore, photocards are also made, following the logic of postcards but with the image of the idols, as well as photo albums, among others. Both the albums and the other mentioned products are elaborated from the point of view of their design, not only from the outside, but also from the inside and the way the contents are presented, since these products are designed to be consumed in an interactive and highly sensorial way. In fact, K-pop fans even enunciate that,

For me k-pop is not just a listening experience. I don't think it’s funny to walk up to someone and say “listen to that song”. If it's k-pop it has to be “watch that video”. K-pop is not just a listening thing. It's not just about the music: it's a general experience. You must see the video, the dance, the music. (Arthur, “O K-pop não é coisa de miúdos”, In Público, 2018).

And also on the question of aesthetics and monetary accessibility,

They are expensive because they come from abroad, but not only that. For example, on a One Direction CD, you have the CD and the plastic cover with the leaflet. In k-pop they invest in photo shoots, in the CD itself. The last one I bought was from G-Dragon, it’s called One of a Kind. It's the size of a bible. There are two versions, bronze and gold, with different photos. They have photocards, posters. The cover itself is padded. (Sara, “O K-pop não é coisa de miúdos”, In Público, 2018).

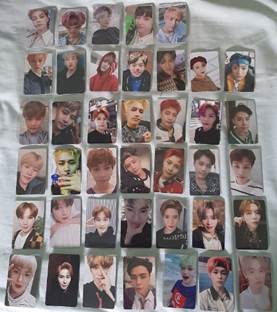

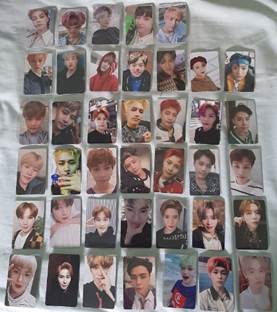

The photo albums, one of the main elements of K-pop products, usually have photos printed on high quality paper. The same goes for the lyric books, which can be bought only as separate booklets from the other products, or they can be included in the content of the photo book or the albums. At the album level, the idols’ photos are staged and concert photos are not used. Photocards, being small-sized photographs, are only of their faces, which can range from selfie-style to professional-style (Oliver, 2020). These can be easily exchanged and collected. So, we are left to ask how these objects, when collected, contribute to the creation of a fandom, as well as to the creation of an identity that is based on the premise of ‘K-pop fan’. Let’s take as an example a sample of the photocard collection of Iolanda, a K-pop fan since 2015, whose collection focuses on her bias, the artist Taiel from the group NCT20,

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 3 Photocards collection of the artist Taeil, from the NCT group, from Iolanda Dias

As Alexandra Borges, 25 years old and a K-pop fan for 11 years tells us during an informal chat at Instagram,

(...) belonging to a fandom creates a certain different identity of ourselves, and the sense that we participate in something and that we belong somewhere, and a lot of friendship and learning comes out of that. Through that learning, certain facts about yourself change and create that different identity. But I think not only identity, but also the way you see the world and other people. Sometimes I think it’s more than a fandom, but a family, because through those people you can be yourself and show your feeling for the group the way you want without anyone criticising you. For me it is a ‘safe place’ where I can be myself without having to worry about other people around me who don’t accept this side of me. (Alexandra Borges, 25 years old, Porto, unemployed, K-pop fan since 2011).

Hallyu. The Portuguese fandom and the Korean cultural wave

Pop culture, as a result of a capitalist system, is one of the main causes for the fact that it is possible for individuals to choose an identity (Kratz & Reimer, 1998), causing a variety of subcultures to emerge (Guerra & Quintela, 2018), which are enhanced by the dissemination of cultural content through the internet (Manago, 2015; Choi, 2015; Jin, 2016). In fact, it is enough to take Alexandra’s speech, presented earlier, as a reference. Nowadays, being a fan is an identity. Or rather, it is even something valued, demonstrating a marked sense of taste. To build this fan identity, there are sets of codes that are followed, not only for the field of K-pop fans, but in a generalized way. If for some musical genres this identity construction is based on lifestyles (Mazur, 2018), for K-pop we can gauge that the same process is based on aesthetic elements, such as clothing, use of vocabulary that is only understood within a restricted group of individuals, by the type of music and, of course, by the most adored idols (Gooch, 2008).

Moreover, at this point we can introduce the considerations of Jenkins (1992) about fan culture very directed to mass culture. However, we consider relevant to adopt Duffett’s perspective (2013), in the sense that we leave aside the negative connotations attributed to fan culture by theorists like Adorno and other sociologists, anthropologists and psychologists, in the sense that fans were often seen as primary representatives of the masses, as alienated consumers and as distant from the processes of cultural production. Also some studies mentioned that being a fan depended on a certain social inadequacy or individual loss, that is, on an absence of dreams or aspirations, only with a focus on the illusions created around idols to compensate for these failures.

The demonstration of identity as a fan can arise as an attempt to build new friendships, but also as an interest in maintaining relationships with those who share a similar taste, hence perhaps the strong growth of K-pop groups on Facebook can be justified (Löbert, 2014). All of them are closed groups, where someone’s acceptance in it, depends on a set of answers facing the genre and the industry, such as ‘What are your 5 favourite K-pop groups’ or ‘Who is your bias’, but also ‘Do you collect K-pop merchandising’ and also, ‘Do you want to buy, sell or trade K-pop merchandising?’22. Thus, in the search for the similar (Chadborn et. al, 2017), collectibles and memorabilia are an essential element to express statements of belonging to a collective as well as a personal identity (Jacobsen & Kristiansen, 2016; Rahim, 2019; Lacasa et al, 2017). As Jenol (2020), Kratz and Reimer (1998) point out, the purchase of these hitherto stated products is nothing more than ways for fans to communicate with each other, but also to make known to which fan group they belong. Jenkis (2004) talks about a social identity which is assumed as a continuation of the personal identity. Now, what does this social identity refer to? It refers to an involvement between that which is the similarity with the other and, simultaneously, denotes the difference. As Duffett (2013) states, fandom is rooted in multiple involvements that are often reinforced by social participation, in this case of K-pop, in somewhat restricted groups and, in this sense, fans are active and not passive as previously thought.

Collecting these items, like almost any other kind of collection, denotes to some extent, a distinct difference between the one who is a fan and the one who is not. Moreover, the objects themselves confer a support to K-pop fans regardless of the individual’s social environment (Jenol, 2020), as identities are not restricted to family background, gender, social class or country of origin, they have rather become something of a broad origin (Giddens, 1991). Within this field, language plays an essential role, also since it promotes an identity based on social relationship, that is, it allows interaction with virtual reality(s) (Locke, 2000). Let us see then that the re-appropriation that is made of the Korean vocabulary by the fans, means multiple spheres of identity performance, causing the creation of a kind of habitus (Bourdieu, 1984) that meets a specific type of cultural capital, skills and dispositions that materialize in ways of life. In fact, there is an appetite to learn the language in non-Korean fans, whether from song lyrics, TV shows or digital content, something that may be due to the need to accentuate a place of belonging to a fandom. As Soompi (2018) refers - and going along with social identity (Jenol, 2020) and the creation of a habitus (Bourdieu, 1984) - dedicated fans will certainly learn to read, speak and write in the language of their idols in order to emphasise closeness to them, as we talked about earlier. It is through the language and the linguistic codes adopted among groups of fans that feelings of belonging to a group emerge and that, consequently, materialize in obtaining memorabilia (Riedel, 2020; Almeida, 2017). Also, the internet assumes a prominent place in this sense, especially because it encourages and allows communication, contributing to the creation of a kind of big brother highly informed about idols, sometimes leading to extremism in fandom (Duffett, 2013; Vieira & Brito, 2016).

Based on this premise, we can gauge that the importance of memorabilia is cemented in the importance of consuming ‘someone’ and everything that ‘someone’ represents (Alberto & Guerra, 2019). Consuming the bias23. Bearing in mind the thought of Todd (2012), it is impossible to have a consumption of something without a deep knowledge about it, however, there is at the outset a greater or lesser possibility of certain fans to participate in the culture, meeting what Bourdieu (1984) states about hierarchy and capital. The K-pop fans consumptions can be seen as products of a hierarchical social system that is institutionalized, through which each fan will create and acquire cultural capital, but that also allows the fan itself to demonstrate certain social and economic capital, establishing itself within a status quo, associating itself to the logics of sharing memories and processes of construction of a collective consciousness (Lévy, 2000).

At this point, we entered the focus of our article, namely the meanings (Silva & Guerra, 2015; Guerra, 2019a). If we think of theoretical currents such as Symbolic Interactionism, we will see that individuals’ behaviours are determined by a set of external micro-scale forces and that it is within this localized social context that they construct and share meanings. This leads us to the concept of the self as Mead (1934) presents it and as Blumer (1969) later works, presenting the three premises of social interaction, namely, i) we act according to the meanings attributed; ii) meanings derive from social action and iii) meanings are managed or changed according to interpretative processes. So, what we intend to envisage is related to the analysis of the construction of meanings by seven Portuguese K-pop fans. More, we intend to understand in what sense memorabilia can contribute to a sense of belonging, as this form of collecting is framed - often - by the belonging to the fandom and, of course, denotes the passion for the genre and the idols, since the objects are preserved in a careful way, as well as follow an expository logic in the rooms of each fan, becoming the same in the new museums (Alberto & Guerra, 2019). As Hellekson (2009) and Turk (2014) describe, the economy of these items gives them satisfaction and makes them feel valued within the community, contributes to their well-being and promotes personal growth and development (Ryff, 1989), while solidifying the K-pop fan identity (Duffett, 2014). In short, we aim to contribute to the advancement of sociology on this theme in Portugal, since we intend to move away from the unilateral vision of the impacts of icons on culture and individuals (Stever, 2009), but to understand how the fans have a connection with the cultural industry and with those same icons, where memorabilia is the fundamental aspect and the main link of connection of these two axes.

Catch Me If You Can: the possible construction of meanings

Continuing the same logic of thought of the previous section, we questioned in what sense the objects cultivate a connection between fans and idols, since these same relations are built from a visual base (Guerra & Alberto, 2021). Now, this visual basis meets the thematic elements that are associated with the K-pop fandom, which we will illustrate further on through the photographs provided by the contacted fans. However, what we can ascertain is that, as Barthes (2005) states, deconstruction processes of K-pop visual materials can (and should) be done, that is, if we remove the context from the idols’ images, the original meaning of the image also disappears. This is where the contributions of sociology are centred, in the processes of deconstruction and eventual decolonisation of a sociology of popular culture. In other words, if we remove the fans from the equation of consumption, the memorabilia items, especially the more specific ones referring to bias, lose their meaning as well as the narrative constructed by the South Korean K-pop industry, since all marketing is done thinking about the fans. If we remove the context and the image from a K-pop album, independently of the group, the visual narratives associated to it lose meaning and it’s these meanings that interest us, as well as the feelings of belonging that are lost and what was a culture created for the world, besides being ruled by a nationalist absence, it would become null and non-existent.

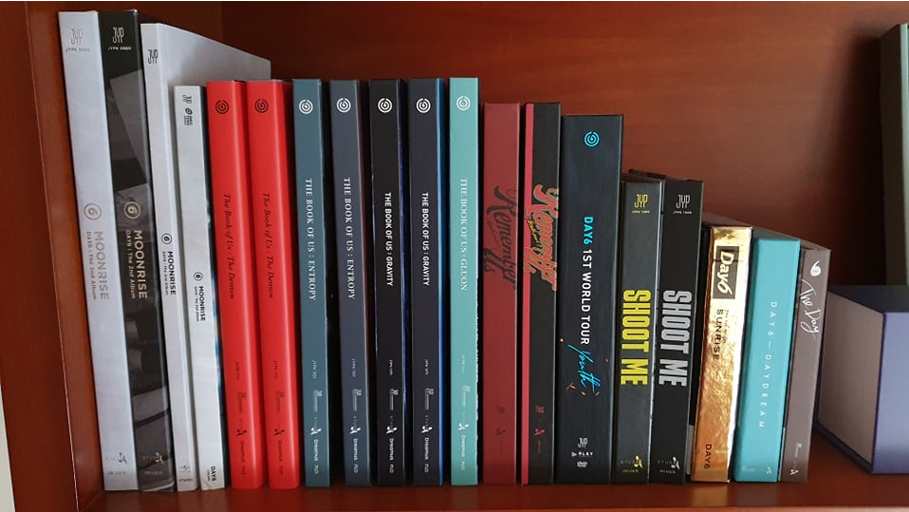

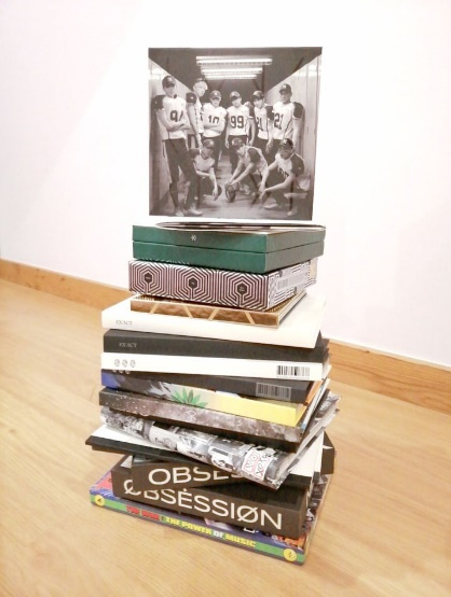

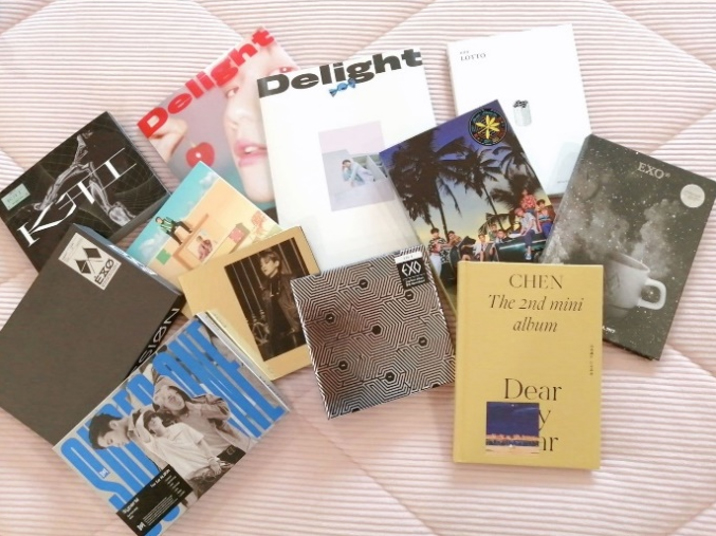

All the items given to us by fans, from albums, photocards, soft toys, lightsticks and others, can be analysed from various angles and from different perspectives. On the one hand, there is the question of authenticity and originality. Let’s see that the album covers themselves are contradictory when compared to the Anglo-American industry, where they are worked on from an artistic point of view. In K-pop, covers tend to be minimalist, but the investment and creative work is inside the album and in the other items that accompany it. This ends up being an extremely attractive factor for fans, more specifically the fact that these are not conventional albums, like so many others in which only the cover differentiates them. This is how the individual symbolic value and collective value is created for a certain product within each fandom and, of course, the interaction with the materials becomes an extremely pleasant and sensorial experience, emphasized by the tactile nature of the objects themselves. We thus take into account the construction of an aura as Walter Benjamin (1994) referred which, in parallel, is maintained through the authenticity of the products. Thus, we mean that it is also through the aura of the objects that fans’ relationships with the objects are cemented, as well as the need to keep consuming them is maintained, especially by the strong relationship that is created with the source of origin and the image of the product. The aura of these objects conveys a feeling of individualization, as opposed to the idea that they are receiving/buying a mass product (Oliver, 2020). In fact, the very format of the albums comes to ensure the idea that only K-pop fans would be able to recognize and, consequently, acquire them. Thus, this idea also comes to emphasize the special character that fans possess for the promotion of the genre. Here are some examples:

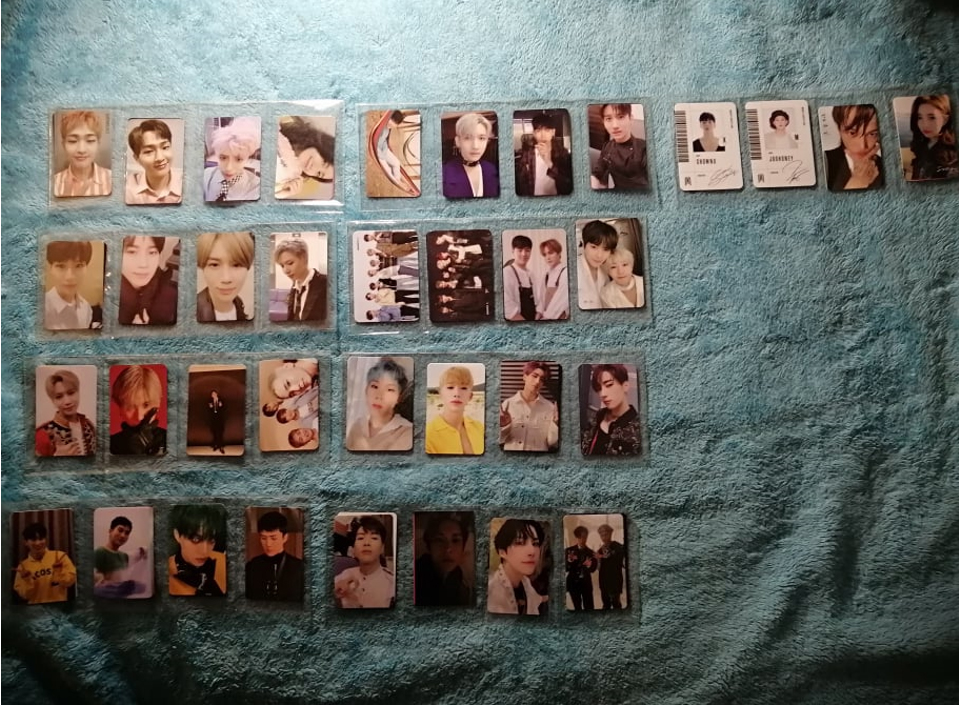

Alongside albums, photocards are also extremely relevant, and are perhaps the most collectible items. Moreover, this is a way to strengthen, as well as to provide continuity, to the sense of community and belonging among K-pop fans (Galloway, 2020). Why is this? Well, when a fan buys a K-pop album, there is an element of surprise as to which photocard will be included, and it may not correspond to the preferred member. Thus, the processes of exchange, sale and purchase of these items are encouraged, with the aim of collecting the ultimate bias25. Moreover, the preservation of the photocards is also a process that cements the affective relationship that is created between the group and the fan, since there is a preservationist feeling (Heinich, 2010) towards them. For example, they are placed in protective covers and are organised according to certain logics. Even in the sent photographs one can see care and concern regarding the way the items are presented, as they are aligned and within skins. In this way, we can consider that these items are a form of material heritage, although they are not yet recognised as such. An example of this care is the collection of Jéssica Barros, a K-pop fan for eight years. In conversation, she mentioned having in her possession 85 photocards and about 66 albums.

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 8 Note: Referring to groups such as EXO, TVXQ26, BTOB27, MonstaX, SuperM28, SHINee29 and NCT. Sample of the photocards collection, from Jéssica Barros

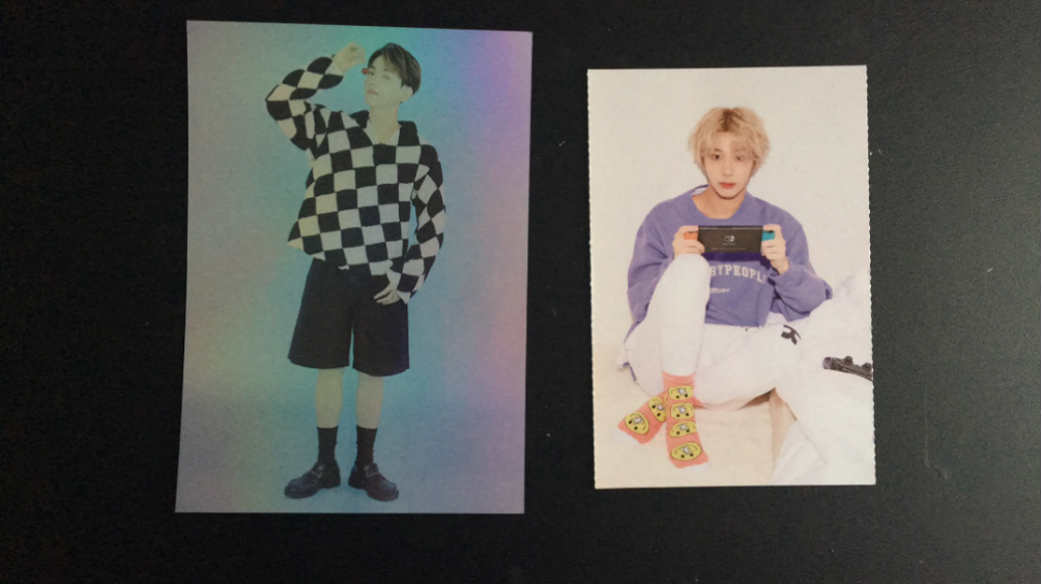

Beatrice also follows the same pattern, an assumed fan of MonstaX and EXO. Her ultimate bias, as she tells us, are the artists Hyungwon from the group MonstaX and Baekhyun from the group EXO and it is around these idols that she has built her collection.

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 9 Photocard of Baekhyun from the album Delight and photocard of Hyungwon from 4th Fanclub Monbebe

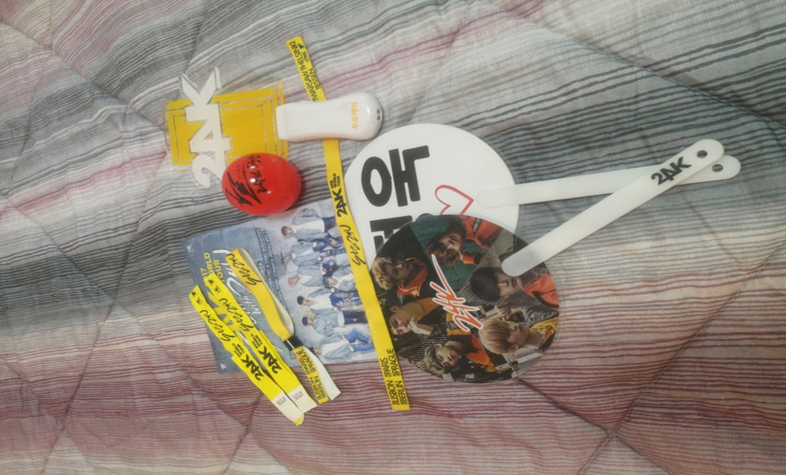

Still regarding the photocards, this preservation logic is also associated to the albums, as well as to other items, such as soft toys, lightsticks and, of course, to other items related to Meet & Greet. This way, the photocards become themselves carriers of meanings within a unique subculture, which aims at indicating a preference for one or more artists, as is the case of Beatriz. The same applies to lightsticks or special items, such as concert bracelets or banners, these rarer in the Portuguese context as K-pop concerts do not take place on a regular basis because this country is considered too small to host the bands’ giant artistic productions. One example is the collection of Andreia Caetano, 28 years old and a K-pop fan since 2016, which includes souvenirs from two concerts in Lisbon and one in Madrid.

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 11 Note: Souvenirs of the groups ATEEZ31, VAV32, ACE33, 24K34, PENTAGON35 and BLOCKB36 Banners, meet&greet photos, concert photos and lightsticks

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 12 Souvenirs from the two concerts of the 24K group in Lisbon (2017 and 2018)

Based on this assumption, we returned to Bourdieu’s contributions (1984) when he enunciates the different types of economic, cultural and social capital. Let us see that the interaction of the authors with these fans, as well as the explanation of each of the photographs provided, denotes a strong cultural capital. Thus, as Oliver (2020) enunciates, this cultural capital manifests itself according to the form of knowledge about K-pop. On the one hand, by the investment made in memorising and/or knowing the names of the albums and whether they are special editions, but also by the time invested in knowing the names of the members and specific characteristics, such as height or weight. Furthermore, knowing the names of the songs, the lyrics and which album they belong to also requires a strong investment, because a true fan knows how to differentiate between a debut and a comeback, something quite common in K-pop. This differentiation is one more marketing strategy that aims to capture the attention of fans (Sun, 2020), reminding us to what was assessed at the beginning of the article, about the fact that there is a need to attend all the live performances, thus meeting this differentiation. So, this knowledge about K-pop, recognized as the aegis of the cultural capital, manifests itself in the intention to buy and consume more items of this genre, appearing as a reinforcement to their personal and collective identity (Jenkins, 1992). Thus, also as a form of recognition and appreciation of the individual and the items acquired, the need to exhibit them arises. Not only the albums, but all the items related to the bias.

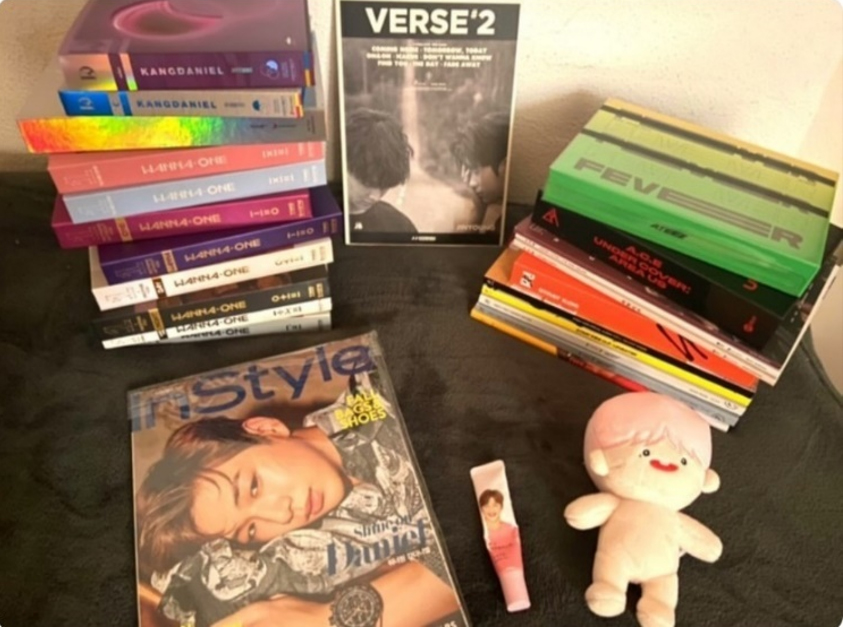

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 13 Collection of photocards and a binder with other photocards (exposed ones are the most cherished)

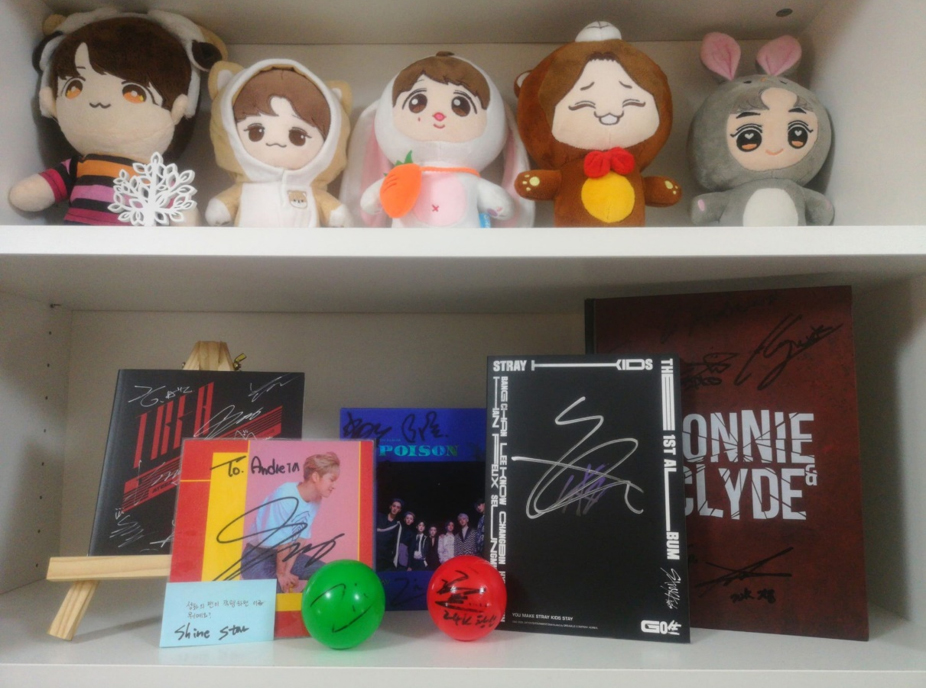

With the image above (Figure 14) we have presented the variety of products that can be collected within the K-pop genre. Thus, in the two photographs, according to Alexandra Borges, a 25-year-old young woman and K-pop fan since 2011, all the items that she esteems the most are present, such as the albums of the groups GOT7, A.C.E, ATEEZ, Stray Kids37 and by the artist Kang Daniel. Again, on the importance of the proximity to the idol (Oliver, 2020), we have (see Figure 16) a set of items that meet this idea, and the magazines are also of important relevance38, as ‘inStyle’, the first in which the artist Kang Daniel featured on the cover, as well as a K-pop Doll of the same artist, and also a lipstick of the innisfree line39 in which the WANNA ONE group40 was the face of the brand. Each member had a different colour lipstick, Alexandra acquired the one of her bias, Kang Daniel. Otherwise, the representations that are constructed around the items, lead us to others, such as authenticity, beauty, monumentality and meaning, which are essential characteristics identified by Natalie Heinich (2017) towards heritage value and which, in turn, can also be identified in memorabilia items.

Thus, we consider that we are facing what Stuart Hall (2005) states about the postmodern subject, since we are facing cultural identities (Williams, 2006) that allow the integration of the individual in a movement that goes beyond the musical taste, but that aims, indeed, at the integration of the individual in an active culture, promoting socialization and the dissemination of ideas with other individuals who share the same taste. This post-modern identity serves as a basis for our understanding of the ways in which South Korean culture is consumed, especially in terms of memorabilia, almost as if it were a way of recognizing it as their native culture. We are thus in hybrid identity processes that emphasize the relationship with the consumed products and that, in turn, contribute to its dissemination. In this way, the fans see themselves as a fundamental element for the dissemination of the genre.

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 15 EXO member Lay’s soft toy and extras and Andreia Caetano’s ultimate bias

Also in the following figure (see Figure 16), Andreia reinforces the previous idea, as she provided us with a detailed description of each of the items. Thus, we ask the reader to read the image from left to right, since we will provide the legend as she indicated. We decided to do so since we have denoted a strong sense of pride in the items, as Andreia goes to concerts and has participated in meet & greet. In parallel, it is also important to demonstrate her knowledge as a fan, her cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984; Oliver, 2020). Another curiosity, being in front of albums signed by her idols, we asked her about the prices, an issue already stated here in the article, and Andreia stated that these would be the most expensive ones she acquired, in fact she even pointed out that the most expensive one is NAMANANA of the artist Lay - her bias - and that it cost 55 euros. So, from this example we can reinforce what was said before, that it is a strong cultural and economic capital, in the sense that, regardless of the price, the focus is on establishing a relationship with the idol, acquiring all the products related to it.

Source: provided by herself.

Figure 16 Note: Ateez ep2 signed by all members; Ateez Illusion version signed by Seonghwa and with an answer to a question; VAV Poison signed by all members; Stray Kids GO signed by Hyunjin; 24K Bonnie & Clyde signed by all members; Green ball signed by Ziu (VAV in concert) and red ball signed by Hongseob (24K in concert) Signed albums, from Andreia Caetano

There are also some examples of lightsticks used in concerts, which are considered an important part of the memorabilia, mainly because they accentuate the presence of fans in the shows, as well as their support to the artists. It is important to note that in these three images we observe the customization of products, since the lightstick of the EXO group of Erica’s collection (see Figure 18) and the one of Jessica’s collection (see Figure 19), although both have flowers inside and have the same format, their colours are different, as well as the positioning of the name of the group.

Thus, it is also important to highlight that the purchase of these items denotes a strong nostalgic feeling, as well as a strong sense of belonging. Moreover, K-pop - within popular music - has become a cultural heritage, in which the memorabilia associated with this genre reveals nostalgic properties (Guerra, 2010) deeply connected to the idols. On the one hand, and meeting what was previously said about the knowledge obtained and demonstrated about the world of K-pop associated with the possibility of making it known, it may cause feelings of fulfilment, as well as give them a sense of belonging since, especially in the Portuguese context, a strong stereotyping towards K-pop fans still remains. These stereotypes (Duffett, 2013) are built from the idea that K-pop fans are introverted, shy and with weak socialization skills, a bit like the stereotypes that exist about fans of manga or comic books.

In a systematic way, we can assess that global audiences connect with K-pop through digital media, thus having implicit a connection between the meaning and the object that, consequently, ends up being shared as a form of communication, through the purchase of albums and other products. These relationships created with the objects exalt multiple reflective elements on consumptions, but also on collective memories (Halbwachs, 1992; Alberto & Guerra, 2019), something as much, or even more, evident because there are numerous fans who have the same bias, or who share the same K-pop items, thus giving rise - and materialising - in distinct types of sociabilities and ways of life (Guerra, 2018; 2019b). The items presented above, as well as the care mentioned regarding the presentation of the items in the rooms, combined with a preservationist logic (Heinich, 2010), point us to the idea of museification (Duarte, 2014) of private spaces. Well, these processes and the collecting practices around K-pop items should thus be taken into account in a sociological approach such as the one we propose here, especially because it refers us to different forms of cultural heritage (Roberts & Cohen, 2014), different symbologies and, of course, enunciates the importance of the materiality of popular culture, namely of South Korean popular culture.

Through the photographs we received, as well as through the informal conversations established by social networks such as Facebook and Instagram, we were able to denote the notion of ‘patrimonial emotion’ (Fabre, 2013), since a set of emotions and feelings is constructed in relation to the idol and the groups, but also in relation to their objects that, in essence, constitute and compose a common heritage that is lived according to a reality of meanings (Godelier, 2008).

MoneyMakerz. Debut or comeback of the Portuguese fandom?

With the elaboration of this article, it became possible to assess that K-pop, besides being a musical genre that is considered as a product of a systematic globalization process (Oliver, 2020), can also be considered as a new way of perceiving the importance of the local context. Thus, parallel to the fact that it is a product that aims at mass appeal, it simultaneously manages to adapt itself to each regional and local specificity, something even more visible with the visibility of each group per country. We can see that, in the collections that were presented, almost always the same groups appeared, such as EXO, Day 6 or StayKids.

In this article, we got a glimpse of a strong wave of memorabilia collection within the Portuguese fandom, an aspect that has been accentuating gradually, also considering the changes within youth cultures. Digital networks are also a factor to be taken into consideration, in the sense that they provide interaction based on the images and productions of idols. Moreover, as Duffett (2015) states, the new environments created about and from the social networks, bring the fandom closer and play key roles at the levels of artistic productions and consumption, since the products are made thinking about the fans (Sun, 2020). Thus, the performances, the appearances, the use of social networks, the songs, the video clips and merchandising - among others - when associated with this musical genre, always assume vast and distinct proportions and materializations, turning it into an even more profitable genre, cementing itself continuously in the young fans’ imaginaries. Another point that this article has highlighted is that fan culture in contemporaneity, at least as far as K-pop is concerned, is not limited to the online universe, materializing in physical and collectible objects, as in the 1980s and 1990s, thus having a duality between contemporary and traditional, exalting a kind of nostalgia (Alberto & Guerra, 2019).

Being a fan is not restricted to the end of a concert or a performance; in fact, it extends to several dimensions of individual and collective social life. If it seemed that the fan identity no longer had the same strength as in the 1980s, 1990s and even in the early 2000s, due to the immensity of mass-produced cultural products, with K-pop it seems to be the opposite. An example of this is the importance given to CDs - something that in American and Western culture is not really the case - without neglecting the importance of digital platforms and vice versa. Thus, we are left to think and reflect on the importance of objects and memorabilia associated with K-pop, mainly from the point of view of the creation of an identity, but mainly from the attribution, sharing and construction of meanings vis-à-vis these items (Guerra, 2019a; Blumer, 1969). Rather than being something temporary, a fever for idols similar to what happened with other western boy and girl bands, the appreciation and demonstration of taste for the groups and the musical genre, even contributed to the permanent creation of a sense of belonging (Ryff, 1989).

In short, with the writing of this article we intended to counter recent studies focusing on the impacts of icons on culture and individuals (Stever, 2009), but also to move away from an economic and commercial view of K-pop merchandising items. So, we consider that it will be important to resume and deepen this issue in future researches, extending the age groups, and also widening the geographic scope, in order to foresee similarities and differences regarding this type of consumption, according to the country of origin of each fan.

Acknowledgements

A word of appreciation to Alexandra, Andreia, Beatriz, Érica, Iolanda, Jéssica, Joana, and Ana Oliveira whose help and availability was indispensable for the preparation of this article.

This article is part of the project ArtCitizenship - Youth and the arts of citizenship: creative practices, participatory culture and activism (reference: Project/Contract PS: 28655) developed by CICSNOVA - Universidade Nova de Lisboa in partnership with IS-UP and funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology, as well as in KISMIF International Conference 2020 - Keep it Simple, Make it Fast! DIY Cultures and Global Challenges 2021.