I. The need to foster local food systemsi

This article will consider as a starting point the insufficient organic food to supply school canteens in Portugal (Delgado, 2020b; Sousa, 2019). Nowadays, institutional demand for local organic food is swiftly increasing due to the rise of local government`s awareness and willingness to improve school meal quality throughout organic and/or local produced food (Delgado, 2020b). Data from the last Agri-food census (Instituto Nacional de Estatística [INE], 2021) shows that there are 3 963 945ha of agricultural land (Portugal mainland and islands) and 91 781ha of idle agricultural land, i.e., there’s still idle land available for food production.

We sustain that a public policy to facilitate land access to produce local organic food to supply school canteens is the perfect entry point to rethink the existing food systems. In addition, we argue that local authorities have the means and power to play a major role in facilitating access to land for farmers. Our argument is supported by international examples as the ones analysed by International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (2017) or the European Access to Land Network (2017). Besides, this article focus on how to find local land and not on the mechanisms by which farmers to whom land access would be given would be compelled to produce organic food.

The topic is not totally new as notably the National Organic Farming Strategy and Action Plan (Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 110/2017, of July 27th; Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, 2017), approved in 2017, aims to: i) integrate organic products such as milk and fruit in school meals; ii) bring organic products in public canteens menus; iii) foster the creation of organic menus in cafeterias. However, in spite of our efforts so far, nobody from Central Government (Direção Geral de Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural), was able to clarify how those ambitious goals are going to be met. The present article, having Torres Vedras as a study case, might be a contribution for this.

In this article we consider the organic farming and food production definition adopted by Council Regulation (EC) Nº 834/20 (Council of the European Union, 2007), i.e., “a combination of best environmental practices, a hight level of diversity, the preservation of natural resources (…) and products produced using natural substances and processes”. We also recognize that the concept of local production is context dependent, so administrative municipal boundaries were considered as the territorial limit. Finally, the scope of this paper is limited to organic vegetables and fruit production due to its feasibility and market value for school supply.

To foster local food systems, land is needed. In 2012, Portugal central government created the national land bank (Law nr. 62/2012, of December 10th; República Portuguesa, 2012) which, in theory should facilitate the access to public land by making rural land for lease and sale more transparent. However, land being made available through the bank is only state owned, rural and a large amount concerning forestry which cannot be farmed. In addition, no comprehensive connection is made between land demand and supply, out of state possession in Portugal.

Consequently, we argue that local production is limited due to the absence of a multi-sector and multi-actors’ approach to bridge demand and supply, notably regarding land access at local level needed to ensure organic food production. There are at least five main reasons that might explain why land at the local level is not easily accessible despite its availability:

Lack of coherence between national organic food demand and local supply - Data from the National Organic Farming Strategy and Action Plan (Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 110/2017, of July 27th; Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, 2017) shows that land used for organic farming in Portugal in 2015 amounts to 6.6% of the total area used for agricultureii accounted in 2009iii. Updated data from the last Agri-Food Census (INE, 2021) shows that this value decreased to 5.3%, although the increase of 8.1% in the area used for agriculture. On top of this, the organic land for horticultural production is only 1.8ha, as a significative amount of land in organic production is devoted to animal feeding, i.e., 145 100ha (69.1%). The scarce territorial presence of organic farming in Portugal, and the current demand, especially in urban areas (Marian, 2018) explains that 49% of fruit and vegetables consumed and 43% of cereals and legumes are imported (data from 2014 to 2016; Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 110/2017, of July 27th; Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, 2017). In total, eleven countries supplied 480 725 tonnes of organic products (data from 2014 to 2016) to meet national consumption.

Land innovative legislation still lacks an implementation strategy - The Action Plan for Organic Farming (Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 110/2017, of July 27th; Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, 2017), although it is not clear how this will be achieved, it is defined that “the area allocated for organic farming should be 12% of the national agriculture land by 2027, and that land for fruit and vegetable, protein crops, nuts, cereals, and other vegetable crops intended for direct consumption or processing should triple by 2027”.

Missing links between urban planning, land access and food - In spite of the passionate and thorough debates among scholars and some practitioners, food from production to consumption has been neglected for decades by both urban planners and agricultural policy makers, as urban planners treated agricultural land as potential building ground and agricultural policies focused on rural areas (Lohrberg, 2016). Portugal is no exception. For long time food has been forgotten in city planning and kept far from urban agendas (Pothukuchi & Kaufman, 1999; Tornaghi, 2014). Nevertheless, integration of food into urban planning is becoming an emerging topic (Cabannes & Marocchino, 2018; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2020; Morgan, 2015).

Missing links between existing food stakeholders and initiatives - In Portugal, the resolution taken by the Council of Ministers (Resolution of the Council of Ministers no. 103/2018, of July 26th; Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, 2018) acknowledges the need of a better integration of currently disconnected food actors and sectors. The Portuguese national platform Feeding Sustainable Cities is a civil society initiative aiming at reshaping the Portuguese food systems, that emerged in June 2018 with 40 members and counting with 400 members in 2021 (Alimentar Cidades Saudáveis, 2021). At national and local levels, several organizations are leading isolated food initiatives, some of them struggling to find land (Delgado, 2015; Kruth, 2015; McClintock et al., 2013). Those food initiatives open a huge window of opportunity for food policy formulation aiming at better feeding cities.

Missing integrated sustainable food strategies at local level - The E-book Alimentar boas práticas: da produção ao consumo sustentável 2020 (Feeding good practices: from sustainable production to consumption; Delgado, 2020a) illustrates the multiplies efforts made by local food champions and some local governments. It highlights the diversity of actors involved, their territorial scale, the multiple spaces where they take place; the multiplicity of entry points through which practices are initiated; their dynamics through time; the wide range of entries in the food chain; the diversity of financial resources used and combined. Not surprisingly, there is not a single initiative or program, from production to consumption, that includes access to land. In line with authors as Angotti (2015), and Prové et al. (2016), we argue that the lack of a coherent and integrated food strategy that considers land access as a starting point deserves attention.

In summary, to explore our argument and research question, we will use Torres Vedras municipality as a study case and a stakeholder approach as methodology. Thereby, section one of this paper provides a brief context regarding the National Organic Farming Strategy and Action Plan (Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 110/2017, of July 27th; Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, 2017) as an additional window of opportunity to foster local food systems and explores why land is a key missing piece. Section two summarizes the existing national public policies regarding land and food to illustrate that in spite of the considerable number of policies there is a need for a holistic approach. Section three puts in perspective common land still available in Portugal. Section four presents Torres Vedras, our study case. Section five explains the methodology adopted. Subsequently, section six summarizes and discusses the findings obtained through a stakeholder’s interviews. Concluding remarks and a call for action close the present article.

II. Local authorities interest on food and farming need a deeper engagement with land

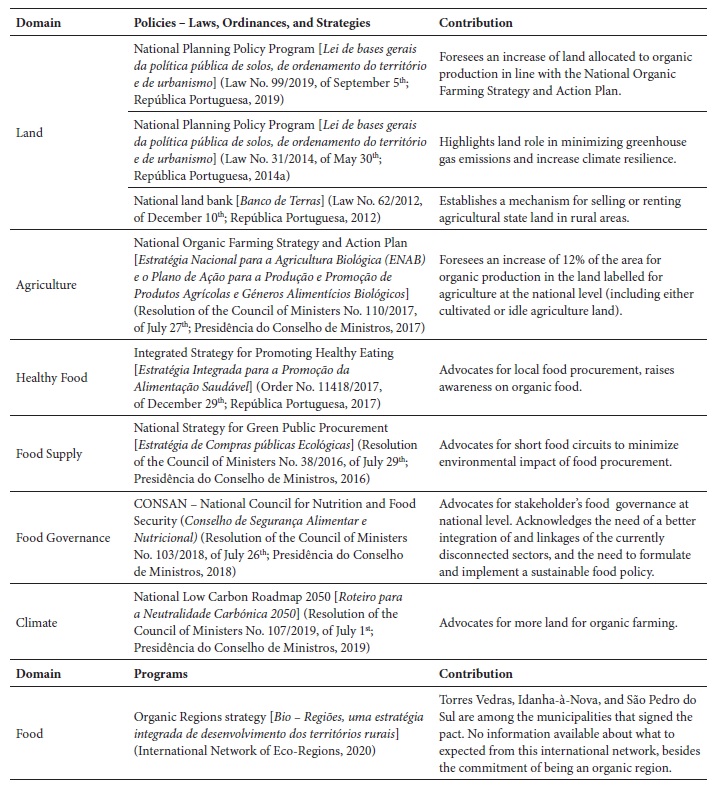

To foster a multi-level land approach a combination of national and local policies is required. To start with, there is a need to acknowledge that central government has tried to do this since 2017, even if with limited success so far. Table I presents a non-exhaustive list of policies directly and indirectly related to the issue of land for food production.

A window of opportunity comes, in particular, from the National Organic Farming Strategy and Action Plan (Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 110/2017, of July 27th; Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, 2017) with several measures regarding the increase of organic production notably, vegetables and fruits as previously mentioned.

As table I illustrates, there is a considerable amount of very well-intentioned top-down policies, embracing laws, strategies, and programs, to be implemented at national level.

Meanwhile, since 2010, an increasing number of local authorities have developed the interest in food, urban gardening (Hortas Urbanas) and the need to reconnect the rural-urban divided, as part of their local development policies and/or their sustainable development (Delgado, 2017; Parceria de Desenvolvimento PROVE, 2013). The reasons behind such municipal choices are very diverse: promoting social cohesion; food awareness; reduction of food waste; helping people in need to be able to reach food, etc. It is time to expand those interest to a more holistic food vision that would be consider an integrated food strategy: promoting local organic food in public schools; restaurants and local markets; developing a land policy to increase local food supply; supporting local businesses and job creation; promoting environmentally friendly forms of farming as a way to manage environmental risks or preserve assets (e.g., land and water resources); or improving their food resilience as part of their climate change strategy.

III. Re-discovering common land for local food production

To understand the common land national background, this section provides a brief literature review and presents the existing common land data in Portugal mainland and the Lisbon district, where Torres Vedras fits in.

The common land is an ancient tradition in Portugal that goes back to the Middle Ages (Brouwer, 1999; Oliveira Baptista, 1994; Paiva et al., 2019). It provides a form of social security for landless poor, who were permitted to pasture cattle and cultivate plots on a temporary basis. In the 1930s, the Portuguese “New State” regimeiv, aware of the existing extensive common land, created in 1936, the Board of Internal Colonization, a body with legal status, and with autonomous operation and administration capacities. The competences of the Board were: “to identify the vacant land reserve of the State and administrative bodies that can be used for agricultural purposes, taking into account the nature of the land, its extension and the benefits of the peoples with regard to their current enjoyment” (Paiva et al., 2019, p. 17). From the moment this Board was created, efforts were concentrated in order to identify in detail the existing common land and its location to better define a national strategy to abolish common land. That decision triggered a strong feeling of revolt and originated a temporary crisis within the government.

Demonstrations were violently repressed and lots of people went to jail, but the baldios (common land) survived. According to Barros (2012) and Paiva et al. (2019) it was the most cunning and oppressive campaign against common land, and for erradicating local communities uses such as pastoralism, gathering firewood and scrubs. The forestation of more than 400 000ha of common land forced many community members to leave herding in spite of local population resistance (Brouwer, 1999; Oliveira Baptista, 1994).

Following the Revolution of April 25, 1974, profound societal changes happened. For the first time, the economic and social role of common land and its community ownership was recognized by the state and incorporated in the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic approved in 1976 (Paiva et al., 2019). After 1976, four relevant public policies were established: in 1976 the Decree-Law No. 39/76, of January 19th (República Portuguesa, 1976), in 1993 the Law No. 68/93, of September 4th (República Portuguesa, 1993), in 2014 the Law No. 72/2014, of September 2nd (República Portuguesa, 2014b) and the last one in 2017 the Law No. 75/2017, of August 17th (República Portuguesa, 2017). In 2008, a National Commission for the Development of Communal Territories was created to ensure sustainable forestation of remaining common land. Information obtained from a civil servant from the Institute of Nature and Forest Conservation (ICNF) indicated that this Commission was currently inactive. This corroborates Luz (2017) statement on ICNF largely not complying with its regulatory status, as foreseen by the Law No. 75/2017, of August 17th (República Portuguesa, 2017).

According to the Law No. 75/2017, of August 17th about the rules on common land and other community means of production, an online public platform should have been settled 120 days after its publication (Article 9), i.e., roughly by the end of 2017. This extremely useful platform would include relevant data on common land such as: geographical coordinates; area; management body; user plan; area subjected to the forestation regime, to name a few. Four years after the law approval, the online platform was still at the planning stage (2021).

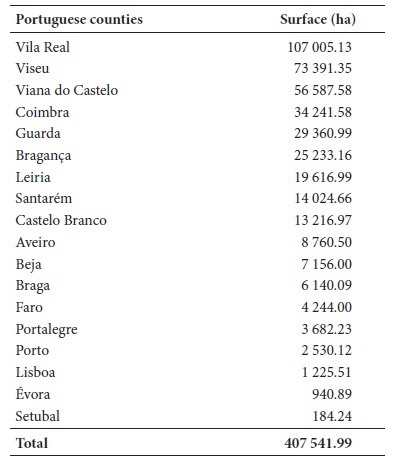

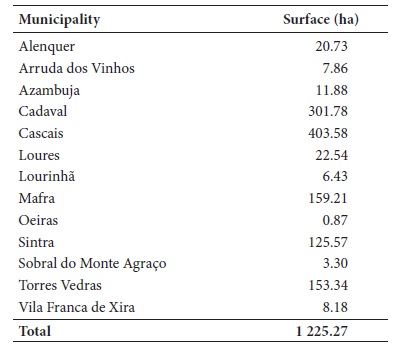

The most accurate information existing so far is still the one from the survey done in 1939 by the Board of Internal Colonization during the dictatorship period. The numbers of hectares are quite impressive as a closer look to table II can illustrate. According to the publication Acknowledgement of the Common Land in Continental Portugal (Junta de Colonização Interna, 1939), there are 407 541.99ha of common land in mainland, especially concentrated in the north and the interior of the country. The common land active in the Lisbon district, in 1939, can be observed on table III. The area of common land is quite high in some municipalities within Lisbon district: for instance, Cascais, a municipality on the outskirts of Lisbon, summed 403.58ha of common land in 1939. Torres Vedras, our study case, comprised 153.34ha of common land. If this land remains available, it is a window of opportunity to produce local food. We will return to this further on.

IV. Towards a policy grounded in local context: Torres Vedras as a paradigm shift

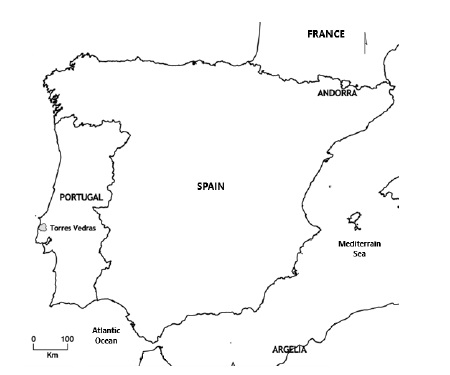

Torres Vedras municipality is located on the outskirts of Lisbon (fig. 1) and comprises 79 465 inhabitants (INE, 2017) within an area of 407km2. Its main economic activity is the third sector (services) that employs 67.1% of the active population, followed by the secondary sector (industry) with 26.7%, and last the primary sector (agriculture and fisheries) with 6.2% (higher than the national average of 3.4%). Torres Vedras is one of the most prominent Portuguese municipality in relation to conventional agricultural, notably polyculture, such as beans and potatoes, and with the largest wine production nationwidev.

Fig. 1 The location of Torres Vedras in Portugal and Iberian Peninsula. Source: adapted from Torres Vedras Municipality (2020)

In 2014, the municipality started a successful Food Program for School Canteens (Programa de Sustentabilidade na Alimentação Escolar - PSAE). In a nutshell, the program aims to promote local economy, environmental sustainability and improve school diet. This is done by facilitating the connection between local producers and local not-for-profit organizations with parishes kitchen facilities cooking school mealsvi. The program provides 720 000 meals a year (2018) to 37 local kinder gardens and 41 elementary schools (4170 students): 1300 meals are cooked per day by the municipal central kitchen, while 2700 come from local not-for-profit parish-based organizations (Rodrigues, 2020). In 2018, the municipality launched an organic school meals pilot program with the explicit aim to be locally supplied.

Today, the number of students below city jurisdiction increased to 6000 and therefore the supply challenge increased as well. The municipality is facing two options, either buying organic food outside the municipal boundaries or increasing local land availability for organic production, possibly considering Mouans-Sartoux municipality approach as referencevii.

In an attempt to choose an adequate solution, Torres Vedras joined national and international initiatives and exchanges on policies and practices, including the ones listed below:

The city is a partner of the BioCanteens Transfer Network (URBACT, n.d.). This network is key for the replication of Mouans-Sartoux’s Food Schools Canteens initiative that fully relies on organic food produced locally.

The city signed the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (Milan Municipality, 2015), an international protocol that brings together over 200 cities committed to implementing coherent municipal food-related policies and programmes.

The city is a member of the international CITYFOOD network, coordinated by the Resource Centres on Urban Agriculture & Food Security ([RUAF], 2019), a global partnership on sustainable agriculture and food systems and ICLEI - Local Governments for Sustainability (n.d.), a global network of over 1750 governments committed to sustainable development. The mentioned network aims to accelerate local and regional government actions on sustainable and resilient city-region food systems.

Regarding land management, the city is undergoing its Master Plan (Plano Director Municipal) revision since 2018 (Direção-Geral do Território, 2021). In short, the Municipal Master Plan sets out the territorial development strategy, i.e., the land-use management as well as other urban planning policies. In addition, the master plan integrates and articulates the guidelines established by national and regional territorial management instruments. Considering this open scenario, it is an extraordinary prospect to integrate the food planning dimension in the city master plan, and to link urban planning, land access and food in Torres Vedras.

V. A stakeholder approach to find local land for food

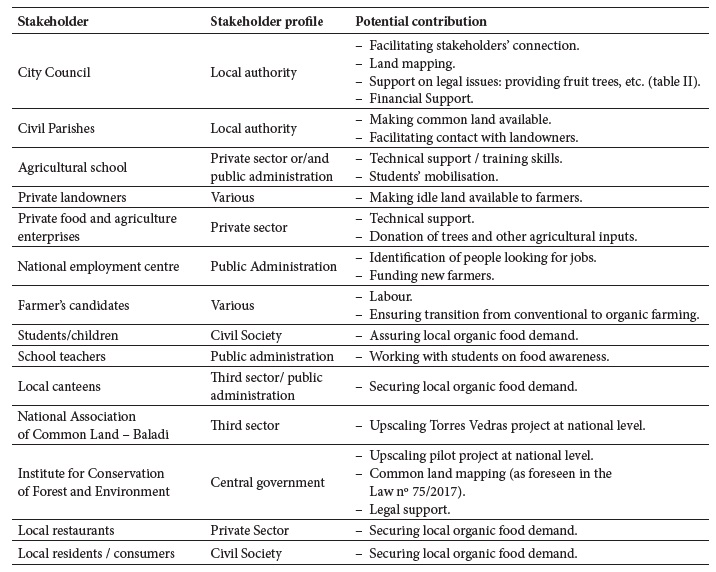

To understand which would be the best land policy approach we used a stakeholder mapping methodology, i.e., a collaborative process of research, analysis, debate, and discussion that draws from multiple perspectives such as determining a list of key stakeholders across the entire concerned actors’ spectrum, based on their relevance, values, and engagement (Taylor, 2019).

The first mapping was brainstormed with the department in charge of the Sustainable Schools Meals Programme. At this point, four city departments were identified: 1) Urban planning; 2) Education and sport; 3) Environment and sustainability; and lastly 4) Social development.

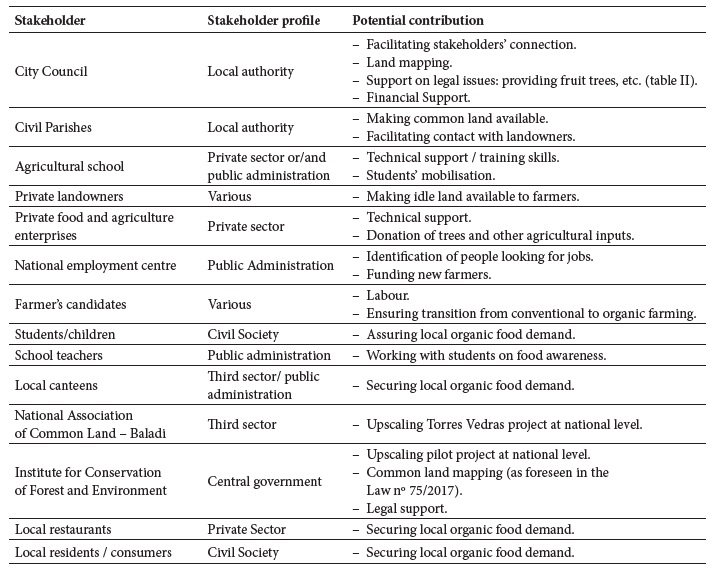

From February to March 2020, we launched a round of meetings with these four council departments. The conversation was based on a semi-structured interview. Its aim was to identify potential department contributions to facilitate local land access in Torres Vedras, then discuss and rank potential policy approaches to facilitate land access to local organic production and, lastly, to identify other potential stakeholders that could be involved. Table IV demonstrates the stakeholders mapped during the first round and how it has evolved through a snowball process that led to a second list of potential stakeholders. The potential contributions of these stakeholders are indicated in the second part of table IV.

Vi. Some findings on how to find local land

Throughout the meetings, we observed a huge potential for collaboration, facilitated by an extremely motivated staff, contrasting with a significant lack of knowledge about the projects carried out by other departments.

The most relevant stakeholder for our research was the representative of Urban Planning department. Nevertheless, municipal land resources are not managed by this department, but is in charge of the Public Procurement and Patrimony one. During the meeting with the mentioned department, the absence of municipal land was confirmed, yet a window of opportunity opened by chance through a civil servant knowledge, that had worked in Carvoeira and Carmões Civil Parish Union, and who was aware of the availability of baldios, i.e., common land.

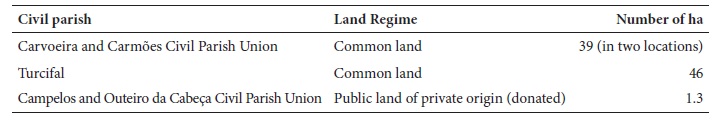

As a follow-up, three out of thirteen Torres Vedras civil parishes were visited. At least two typologies of land regime were found: 1) common land, and: 2) private owners donated land to civil parishes in 2000 that, subsequently, became public land. Torres Vedras common land is in two out of its thirteen civil parishes: Carvoeira e Carmões Civil Parish Union, and Turcifal (table V). Based on information given by the mentioned civil parishes representatives, Torres Vedras common land area increased from 153.34ha in 1939 to 172.00ha today.

A significant amount of common land in Carvoeira and Carmões Civil Parish Union is idle. According to the parish president a touristic project is a possibility under discussion. The remaining land is occupied by wind turbines. In the parish of Turcifal a significant amount of forest land is rented to a national paper company. There is also an ongoing project for an orchard, and idle land that could be available for local organic food production, in particular horticulture, orchards, and animal grazing. Grounded on a statement of the Turcifal civil parish representative, human resources for farming can be found if demand for food production exist. Figure 2 shows common land in the civil parish of Carvoeira and Carmões Civil Parish Union and in Turcifal civil parish.

Regarding specifically common land, two other relevant stakeholders were interviewed. First, the National Association of common land - Baladi (third sector), and second the Institute for Conservation of Forest and Environment (Instituto de Conservação da Natureza e Floresta), a state body who is today managing common land in Portugal. Beyond city department and civil parishes, a set of additional local stakeholders should be involved in the collaborative process. Table VI gives some insights on potential contributors.

Fig. 2 Common land in the civil parish of Carvoeira and Carmões Civil Parish Union (left) and in the civil parish of Turcifal (right). Colour figure available online. Source: C. Delgado (2020)

In conclusion, together, two civil parishes, Turcifal, and Carvoeira and Carmões Civil Parish Union hold 85ha of common land available which could produce local food for the benefit of the community. In addition, Turcifal`s common land is under a special landscape regulation (Edital No. 1169/2015, December 22th; Município de Torres Vedras, 2015) which support and protect traditional land uses notably agricultural ones. Torres Vedras enjoys outstanding facilities to implement a public policy fostering land access. To move forward the municipality should work with the civil parishes on the most suitable common land use model.

VII. Final remarks - a policy approach to turn land available for farming

Local authorities can turn idle land into the decisive element to increase local food system ability to fully supply primarily local schools’ canteens as well as local consumers. To do so, local authorities should develop a sustainable food vision, strategy, and policies for their territory regarding food from “production to consumption”, in coherence with other existing municipal activities and programs.

Grounded on Torres Vedras study, we acknowledge that local stakeholders as authorities, local organizations, farmers, consumers, among others, have unique skills that need to be considered and combined in order to develop a more effective and sustainable local food systems. We acknowledge as well that changes require political will and commitment. At the same time, changes are easier to happen at local level where decision making structures are lighter and stakeholder connections are easier to build.

This being said, we argue that idle common land should be identified and mapped out by local authorities. Those lands should be made available to organizations and farmers willing to supply primarily local schools’ canteens and local consumers as well. From the local authority’s political point of view, at least four reasons substantiate such a proposal:

In case common idle land is not being used, public resources are not used and bear an additional maintenance cost that is being indirectly supported by taxpayers. Turning that land available for farmers should be the prime option considering the following: 1) common land must be re-appropriated for uses bringing benefits to the community; 2) common land is in danger of being privatized; 3) there is an urgent need of rescuing the meaning of commons and common good. Food should be seen as part of it, in particularly food for children and vulnerable people;

Local authorities should have a more pro-active role regarding land needs for local organic farmers to fulfil the needs of local communities in uncertain times. Food is today considered a life sustaining function. The political motto “let´s use our land to feed our children” can raise community support and could be a powerful and consensual starting point;

No significant additional budget is required to kick off the process, as implementation costs are quite limited. What is needed is political will and a person with negotiation skills from local authority staff. For instance, trees for planting orchards or seedlings can come from municipal nurseries; available labour force could be identified through the unemployment national centre or from new leaseholders’ farmers or even, by agricultural schools as part of their practical training;

Such policy can be implemented straight away, and results can be obtained during the next harvest, in case land is made available. Given the food shock caused by the uncertain times we are living, “reclaim our land today” could not be more on the right time.

In conclusion, local authorities are becoming aware of the urgent need to be more food self-sufficient notably to supply local school canteens. To do this, land availability needs to be centrally taken into consideration. When common land exists, a land access political framework to facilitate farmers and organizations willing to supply local schools, should be facilitated by local authorities. According to our research field, cooperation across city departments and local stakeholders is possible, and could spearhead an integrated food policy to turn idle land into a decisive element of the local food system. Finally, local authorities are the key players in such a process as they have the resources and the power to lead the change.