1.Introduction

Public healthcare systems worldwide are undergoing profound transformations as they grapple with the challenges posed by an aging population (Cristea et al., 2020). One notable trend is the escalating reliance on unpaid caregiving to meet the ever-growing care needs (Lindt et al., 2020; Medicine et al., 2008). This shift reflects a broader societal expectation that families should bear the responsibilities of caregiving, often without adequate financial and other support structures in place (Willert & Minnotte, 2019). As the global demographic shift towards an older population intensifies, these demands on unpaid caregivers are poised to rise exponentially, raising important questions about unpaid caregiving arrangements. Unpaid caregivers are defined are family members, neighbours, and/or friends who provide unpaid care to someone experiencing a diminishing physical or mental ability, or chronic illness. Unpaid caregivers often find themselves navigating a complex web of responsibilities encompassing emotional support, medical assistance, and daily living activities (del-Pino-Casado et al., 2021). This multidimensional role can place immense responsibility on caregivers who often grapple with the lack of formal training and resources required to address the diverse needs of care recipients. The assumption that caregiving is a natural extension of familial obligations neglects the intricate and demanding nature of the tasks involved. This oversight results in unpaid caregivers being ill-equipped to handle the complex medical, emotional, and logistical aspects of providing care, leading to potential negative consequences for both the caregiver and the care recipient (Broxton & Feliciano, 2020; Schulz et al., 2012).

Unpaid caregivers play a crucial role in supporting individuals in need. Research exploring the experiences and needs of unpaid caregivers is essential to understand their caregiving challenges and support them in their role as caregivers. While quantitative studies may provide a macro-level understanding of caregiving dynamics, they often fail to capture the intricacies and subjective dimensions of the caregiver's journey. The lack of in-depth qualitative exploration hinders our ability to comprehend the diverse challenges, coping mechanisms, and emotional toll experienced by caregivers. Arts-based methods have emerged as a unique approach to delve into the world of unpaid caregivers, offering a creative and expressive avenue to capture their lived experience (Bourne et al., 2020; Lang et al., 2014; Yoon Irons et al, 2020). This scoping review sets out to explore what is known about how arts-based approaches are being used in the context of unpaid caregiving research.

1.1 Background of Arts-Based Methods

Barone and Eisner define arts-based research is defined as “an approach to research that exploits the capacities of expressive form to capture qualities of life that impact what we know and how we live” (2012, p. 5). According to the authors, arts-based research uses the strengths of the arts to produce new information, insights, and perspectives in a variety of fields and disciplines, such as the humanities, social sciences, education, health, and community development. Through this strategy, deep and nuanced aspects of the human experience can be explored in a way that is frequently not achievable through conventional research approaches alone.

Arts-based approaches and practices can encompass a diverse range of methods and practices, but some of the most common methods include, according to Patricia Leavy (2019, p. 4), are:

• Literary forms: essays, short stories, novellas, novels, experimental writing, scripts, screenplays, poetry, and parables;

• Performative forms: music, songs, dance, creative movement, theatre;

• Visual arts: photography, drawing, painting, collage, installation art, three-dimensional art, sculpture, comics, quilts, and needlework;

• Audiovisual forms: film, video;

• Multimedia forms: graphic novels; and

• Multimethod forms (combining two or more art forms).

These methods can be applied individually or in group settings.

1.2 Arts-Based Methods in Caregiving Research

Arts-based methods in research with unpaid caregivers have gained attention due to their potential to provide a deeper understanding of the caregiving experience. Within health research more broadly, incorporating creative arts elements into research has been found to help tap into the emotional and psychological aspects of lived experience that may not be easily expressed through traditional research methods (Fraser & Sayah, 2011).

Three existing reviews explore the use of specific creative methods with caregivers of individuals with neurological conditions, dementia, and patients in a radiation oncology unit. Bourne et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review focusing on dyadic arts interventions for individuals with dementia and their caregivers, finding that participants enjoyed the activities and reported positive effects of participating. Lang et al. (2014) carried out a systematic review exploring the effects of art therapy on caregivers of cancer patients, indicating that this kind of approach effectively reduced stress among caregivers. Yoon Irons et al. (2020) conducted an integrative systematic review of creative arts interventions for older unpaid caregivers of individuals with neurological conditions, underscoring the psycho-social benefits of creative arts interventions for caregivers in this specific demographic. These reviews provided important information on the effectiveness of specific arts-based methods and interventions amongst unpaid caregivers of particular populations. However, to date, there is no comprehensive review that focuses on all art forms and methods to understand unpaid caregivers' experiences. Therefore, this scoping review aims to synthesize available evidence of all arts-based and creative methods more broadly with unpaid caregivers.

As a review method, a scoping review is able to address broader questions than a systematic review, offering the possibility to identify knowledge gaps and map out current evidence (Peters et al., 2020). Scoping reviews allow for the inclusion of different study designs, making it possible to capture an overview of current literature on a particular topic (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). This is thus a suitable method given the exploratory nature of the question being considered in this review.

This scoping review examines existing research to analyse the impacts of arts-based methods on research with unpaid caregivers. The review included 19 English language peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2007 and 2022.

2. Review Question

The overarching research question guiding the scoping review is: What arts-based methods are used to explore unpaid caregiving experiences in Canada and internationally?

Sub-questions:

What are the impacts of arts-based methods on research with unpaid caregivers?

What are the advantages and challenges of using arts-based tools in interventions for unpaid carers?

Within the JBI’s recommended PCC (population, concept, and context) framework (Pollock et al., 2023), this review’s population is unpaid caregivers, the concept of focus is the use of arts-based methods, and the context is caregiving research.

Keywords: arts-based, unpaid caregivers, research, interventions

Eligibility Criteria

The scoping review limited inclusion to peer-reviewed publications published in English between 2007 and 2022. Given the scarcity of available literature on arts-based approaches to caregiving research, a 15-year eligibility was deemed appropriate to maximize the number of eligible papers while remaining current. The review was limited to English language publications as this is the only language all authors have in common. Peer-reviewed publications were exclusively considered in order to maintain a high-quality review. Additionally, to be included, papers needed to discuss both the provision of unpaid care to older adults by unpaid, informal and/or family caregivers and the use of arts-based methods related to caregiving (either as a research method or in the context of an intervention). Papers were excluded if they only addressed paid caregivers. Likewise, papers were excluded where the provision of care for children (unless adult children) was discussed. Papers that discussed both recipients of care and caregivers were included so long as they discussed outcomes for caregivers.

3.Methods

Building on the methodological work of Arksey and O’Malley (2005), this review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for Scoping Reviews (Peters et al., 2020; Pollock et al., 2023) to conduct a scoping review of arts-based methods used with unpaid caregivers. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Trocco et al., 2018) was followed for reporting. No protocol was registered.

3.1 Search Strategy

A Trent University research librarian was consulted in the development of the search strategy. The strategy was then refined through discussion among the authors. Six bibliographical databases were chosen to be both comprehensive and feasible (Levac et al. 2010). To capture both research-based and intervention-based papers, both medical and social science databases were consulted, namely: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest, Sociological Abstracts and Web of Science.

Database searches took place in the month of December 2022. Final search results were exported to Mendeley, and duplicates were removed.

Databases were searched for key terms of caregiver (carer/caregiv*/informal caregiv*/family caregiv*) and arts-based methods (arts-based methods/creative methods), as well as a publication date filter for 2007-2022. Where possible, limits for adult participants were also used. The database searches were conducted by the first author. Following the JBI search process (Peters et al., 2015), the reference lists of all identified papers were searched for additional relevant papers.

3.2 Source of Evidence Selection

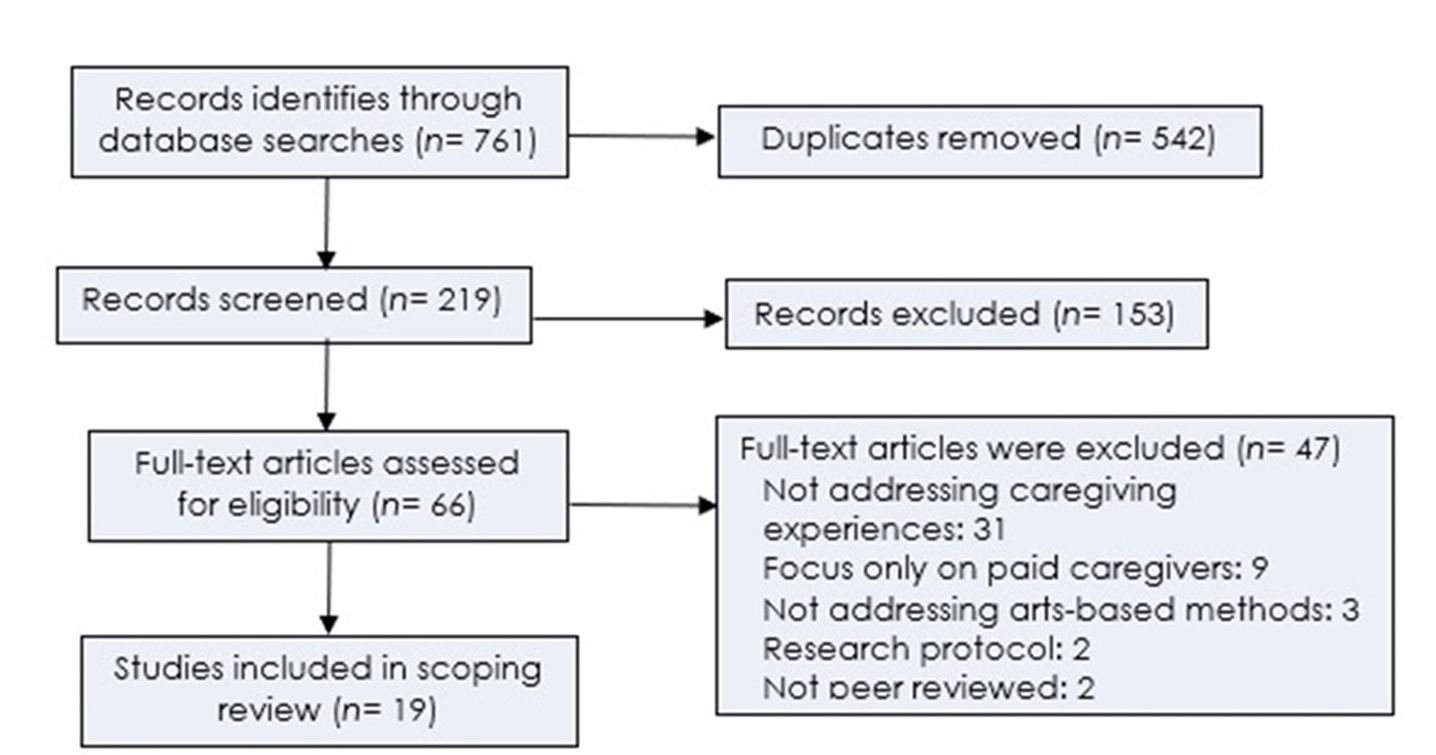

Following the search, all identified citations were collaged and uploaded into Mendeley 2.105.0/2023 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and duplicates were removed. Manuscript titles and abstracts were then screened by First Author and Second Author for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review. Potentially relevant sources were retrieved in full, and their citation details were imported into Mendeley 2.105.0/2023 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands). The full text of selected citations was assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by First Author and Second Author. Reasons for the exclusion of sources of evidence are noted in Figure 1. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved with the input of Third Author.

4.Data Extraction

A data-charting form was jointly created to determine what data to extract. Using Excel, two reviewers charted the data independently, calibrating the form together in an iterative process.

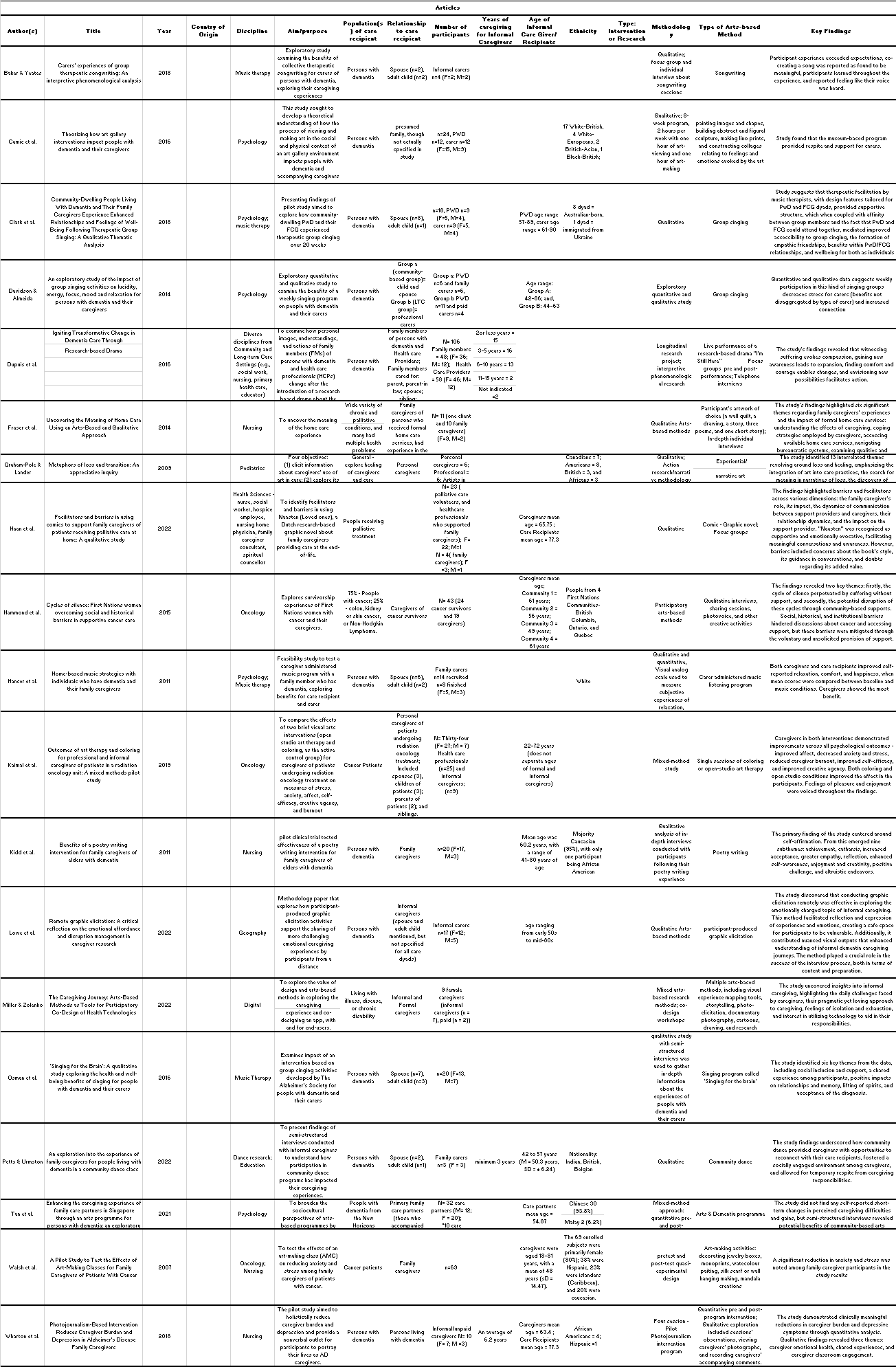

Data items charted included characteristics of articles as well as key findings. Descriptive data included publication details such as authors names, year of publication, country in which the research took place. Data about the population were also charted, including number of participants, population of care recipients, relationship between care recipient and caregiver, age of caregiver/care recipient, ethnicity of caregiver/care recipient and years of caregiving experience. Whether the article presented findings from an intervention or outcomes of a research process were also charted. Details about the aim/purpose of the article were also charted, along with overall methodology as well as the type of arts-based method used. Finally, key findings were charted (see appendix 1).

5. Findings

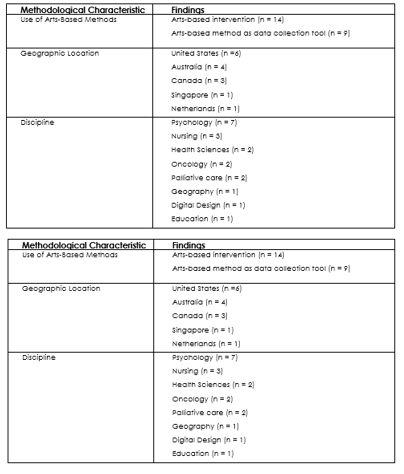

The review yielded studies where arts-based methods were used as data collection tools (n = 9) and intervention research where arts-based methods were used as part of the intervention itself (n = 14), with some including both unpaid caregivers and care recipients (n = 5) while others focused on unpaid caregivers (n = 9).

Of the 19 studies reviewed, the majority were carried out in the United States (n = 6), followed by Australia (n = 4), Canada (n = 3) and the United Kingdom (n = 4), with few from Singapore (n = 1) and The Netherlands (n = 1).

Most of the studies reviewed come from the caring professions, most prominently from psychology (n = 7). Nursing studies also figured prominently (n = 3), followed by health sciences (n = 2), oncology (n = 2) and palliative care (n = 2). Other disciplines represented in the reviewed studies include geography (n = 1), digital design (n = 1) and education (n = 1) was also analysed.

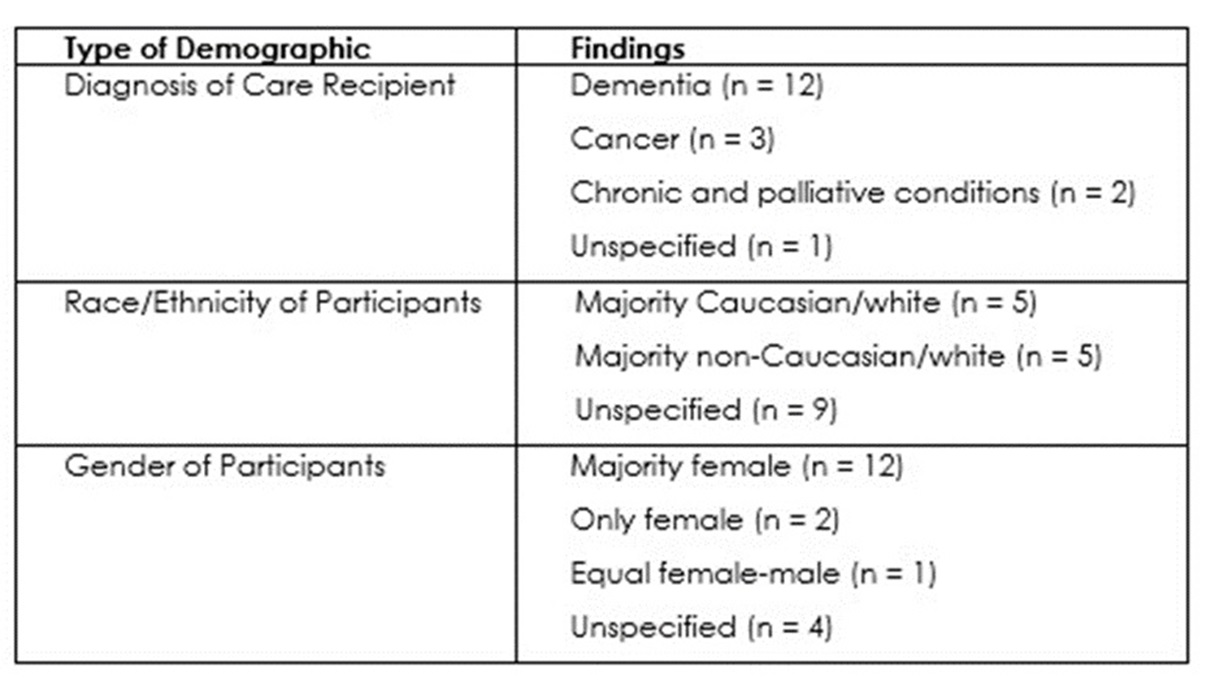

The majority of the studies addressed experiences of unpaid caregiving for a person living with dementia (n= 12), and cancer (n= 3). Studies explored caregiving for a variety of chronic and palliative conditions (n= 2), and other studies were unspecified with respect to the condition of the care recipient (n= 2).

Race and/or ethnicity of participants was not always addressed in the review studies. Where this data was available, it showed limited diversity across the unpaid caregivers included in these studies. The unpaid caregiver participants in the majority of the reviewed studies are predominantly Caucasian from Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. The exceptions to this are: Hammond et al. (2017) focus on First Nations cancer survivors and their caregivers in Canada, Petts and Urmton (2022) explore the experiences of participating in a community dance program for family caregiver where two of the three participants where South Asian, Walsh et al. (2007) undertake art-making classes amongst caregivers of cancer patients in the United States where 20% of their participants are Caucasian, Wharton et al. (2018) undertake a photojournalism pilot project to explore caregiver burden with two African American participants and one Hispanic participant, and Tan et al. (2022) who are studying an arts and dementia program among predominantly (93.8%) Chinese participants in the Singapore context.

Gender was more consistently reported on than race and/or ethnicity in the reviewed studies. Most reviewed studies had more female participants than male (n = 12), with many reporting more than twice the number of female to male participants (n = 7). One study consisted of an equal number of female and male participants and two studies had only female participants.

The results of the thematic analysis are described in the following subsections.

5.1 Arts-Based Methods Used in Reviewed Papers

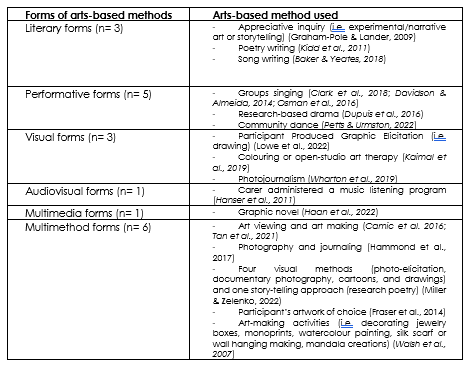

Returning to Leavy’s (2019) categorization of arts-based methods, the following is a breakdown of the forms of arts-based methods used in the reviewed studies (interventions have been indicated in italic).

Multimethod forms, including two, or more, arts-based methods, were the most popular amongst reviewed studies, with an even split between intervention research and arts-based methods research. This is followed by performative forms which included only intervention research, of which singing was the most common. Literary and visual forms were also well represented.

5.2 Using Arts-Based Methods for Data Collection or Data Creation

The scoping review findings suggest that the use of arts-based methods for data collection can have a positive impact on caregivers and the caregiving experience. Arts-based research methods were also noted to help nurture a safe environment for participant expression, particularly in the emotionally charged context of caregiving (Fraser et al., 2014; Lowe et al., 2022; Graham-Pole & Lander, 2009). Lowe et al. (2022), who carried out their interviews remotely, credit their graphic elicitation method for allowing participants to be vulnerable despite the physical and social distance involved in phone interviews.

Arts-based methods can help caregivers gain a deeper understanding of themselves and their caregiving experiences and lead to increased self-awareness and self-care for caregivers (Miller & Zolenko, 2022). The non-verbal nature of visual methods is also reported to offer participants opportunities for reflection (Hammond et al., 2015).

5.3 Using Arts-Based Interventions

The use of arts-based tools within caregiving interventions has been reported to offer a myriad of benefits, contributing significantly to the well-being of both caregivers and care recipients. One prominent advantage is the enhancement of contentment and social engagement (Clark et al., 2018; Davidson & Almeida, 2014; Hanser et al., 2011; Osman et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2021; Warton et al., 2018). Through artistic activities, individuals involved in caregiving experience a positive influence, with stress reduction being a notable outcome (Clark et al., 2018; Davidson & Almeida, 2014; Hanser et al., 2011; Kaimal et al., 2019; Kidd et al., 2011; Osman et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2021; Walsh et al., 2007). This positive impact extends to fostering a reconnection between caregivers and the individuals they care for, as evidenced by studies conducted by Clark et al. (2018), Petts and Urmston (2022), Osman et al. (2016), and Tan et al. (2021).

Furthermore, the use of arts-based tools has been recognized for providing caregivers with a sense of being seen and heard, as elucidated by Baker and Yeates (2018). Additionally, these interventions facilitate the creation of connections among caregivers, offering them a supportive network, as emphasized in studies by Kidd et al. (2011) and Warton et al. (2018). The process of engaging in artistic activities also promotes self-reflection for caregivers, aiding in personal growth and understanding, as observed in works by Baker and Yeates (2018), Kaimal et al. (2019), and Kidd et al. (2011). Moreover, arts-based caregiving interventions are acknowledged for providing respite to caregivers, allowing them a moment of reprieve from their demanding responsibilities (Camic et al., 2016; Petts & Urmston, 2022; Warton et al., 2018).

Despite the extensive exploration of the benefits, it is noteworthy that challenges or drawbacks associated with the use of arts-based methods in caregiving interventions were rarely discussed in the reviewed literature.

The focus has primarily been on the positive impacts, suggesting a need for further research to comprehensively understand the potential limitations and to then address them in the implementation of these innovative approaches.

Of note, two intervention studies reviewed employed arts-based methods as tools for raising awareness about illness and caregiving experiences (Dupuis et al. 2016; Haan et al., 2022).

6.Discussion

Data about the race and/or ethnicity of participants was often absent in the reviewed studies. When this data was available, participants were predominantly caucasian/white, with 3 notable exceptions. This suggests both that more nuanced reporting about race and/or ethnicity, and that arts-based research and intervention work is needed amongst a more diverse population of unpaid caregivers.

While the gender of participants was often reported on, the strong majority of female participants present in most of the reviewed studies reflected the gendered reality of care work (Ophir & Polos, 2021). The reviewed studies did not address the ways in which experiences of caregiving are profoundly shaped by gender, suggesting that applying a gender analysis in future research could be worthwhile.

Though unpaid caregivers were often included in interventions, where unpaid caregivers and care recipients were both included, studies often had care recipients as their primary focus. While this generated some interesting insights, more arts-based research and interventions which seek to explicitly address caregiving concerns and experiences are needed.

Additionally, 12 of the 19 studies reviewed focused on caregivers of people living with dementia. Though dementia is an important focus, new research or intervention work could broaden the application of arts-based methods to a greater range of caregiving experiences.

Lastly, within literature on arts-based methods, there seem to be an emerging discussion on the distinction between active and passive forms of arts-based methods (Yoon Irons et al., 2020). This discussion draws attention to the differences that might arise between the use of methods where the participant is doing/making and where the participant is listening/watching. Two of the studies reviewed would be considered passive (Hanser et al., 2011; Wharton et al., 2019). From the reviewed studies, it appears that the experiential element of the active forms of arts-based methods have the added benefits of more fully engaging participants. It would be worthwhile exploring whether, and if so how, this distinction is useful for the design and implementation of arts-based methods and interventions.

7.Final Considerations

The use of arts-based methods in research with unpaid caregivers aligns with the broader goal of enhancing caregiver and care recipient experiences. By incorporating creative approaches, researchers can not only document the challenges faced by caregivers but also highlight their resilience and coping strategies. Understanding the multifaceted experiences of caregivers through arts-based methods can lead to more tailored and effective support programs that address their unique needs.

The use of arts-based methods in research with unpaid caregivers offers a promising avenue to explore the complexities of the caregiving journey. Future research can shed light on the impact of creative interventions on caregiver well-being and pave the way for more comprehensive and empathetic support systems.