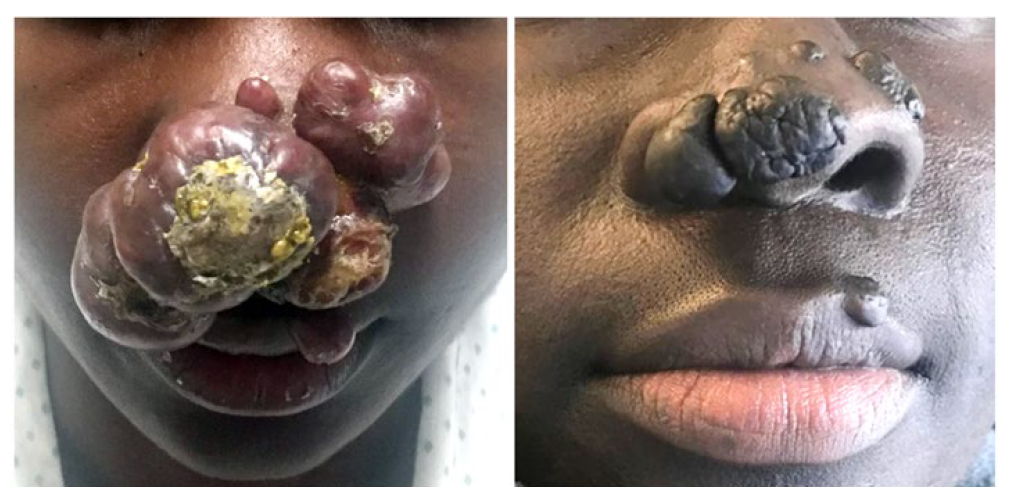

A 36-year-old woman from Guinea-Bissau was evacuated to Lisbon, for a neoplasm of the nasal pyramid, with eight-month evolution associated with likely cutaneous dissemination of similar smaller lesions.

At admission, it was described a multilobulated lesion of the nose, with approximately eight centimetres, associated with a lesion of the upper lip, and local invasion of the skin. (Fig. 1, left) Other smaller similar lesions, in the thorax, limbs and vulvar mucosa were also described at this point. The patient mentioned mild haemoptysis, amenorrhea, asthenia and unquantified weight loss. No relevant personal nor familial history were known.

The initial laboratory evaluation diagnosed HIV-1 infection and the patient was transferred to the Infectious Diseases department. At this point a biopsy of one of the smaller dorsal lesions was done.

During inpatient stay an HIV-1 viral load of 1.910.000 copies/ mL and a lymphocyte T CD4+cell count of 184 cells/μL were documented. Mild anaemia and leucopoenia was also diagnosed. The serologic reaction to HHV-8 IgG was positive

and pregnancy was ruled out.

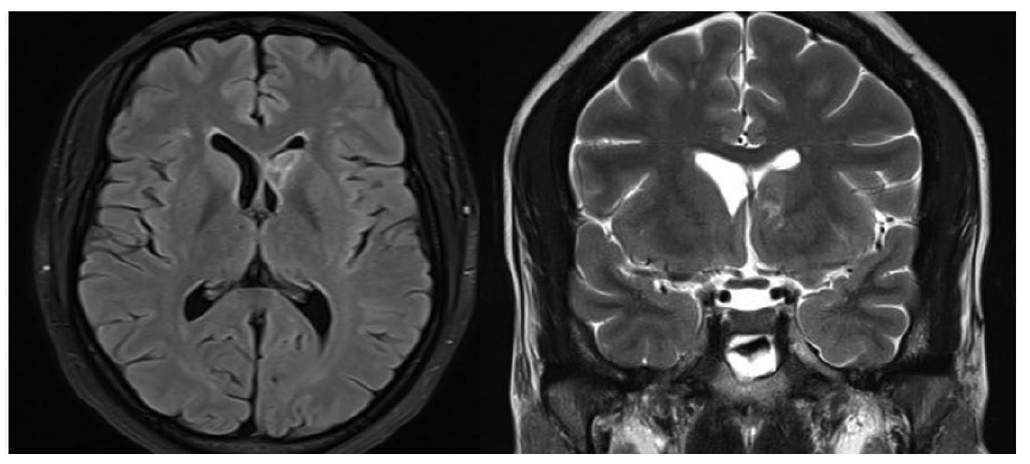

A facial and cranioencephalic computed tomography (CT) described nodularity and mucosal thickness of paranasal sinus, and later magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an oval lesion measuring 18 mm partially filling the left frontal

horn of the lateral ventricle, unspecific in nature (Fig. 2). The cerebrospinal fluid analysis had no chemical nor cytological abnormalities. The thoracic CT described multiple nodules in both lungs, with peribronchovascular distribution. The abdominopelvic CT showed no alterations.

A bronchofibroscopy was performed, where mucosal lesions compatible with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) were described.

The bronchoalveolar lavage had a positive nucleic amplification test for HHV-8.

The diagnosis was confirmed after the result of the biopsy of one of the dorsal lesions.

The patient was immediately started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), with abacavir/lamivudine/dolutegravir, while genotypic drug-resistance test was ongoing, also starting chemotherapy with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD), after one week of inpatient stay, when the histopathologic result of KS was made available.

The genotypic drug-resistance test documented resistance mutations to nucleoside and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and therefore HAART was changed to dolutegravir and darunavir/cobicistat.

During inpatient stay, she was submitted to two cycles of chemotherapy and maintained HAART, with no significant side effects whilst showing marked clinical improvement both in reduction of the dimensions of the nasal lesions and total number of skin lesions. (Fig. 1, right)

The patient is currently under clinical follow-up at the Infectious Diseases department and the Oncology department, having already completed the full course of chemotherapy. Six months after beginning of HAART, indetectable viral load and

TCD4+lymphocyte cell count of 350 cells/μL were documented. Further evaluation after end of treatment showed a favourable evolution of the lung lesions as well as retraction in size of the brain lesion.

Even though the extension of the nasal lesions raised doubts about the diagnosis, KS should always be suspected in a patient with cutaneous neoplasms and HIV infection.1-3

The advanced immune depression and the positive PCR for HHV-8 supported this diagnosis. Nonetheless, the histopathological exam was essential to the definitive diagnosis. Due to exuberant cutaneous and visceral extension, the patient was started on PLD, in addition to HAART, achieving rapid response and positive clinical evolution.

Although KS brain involvement was suspected, this hypothesis was not confirmed with a biopsy given the risk of the procedure. The MRI had unspecific characteristic features (single intraventricular homogeneous lesion), and the cytological exam of the cerebrospinal fluid was normal. As such, and weighing pros and cons in an asymptomatic patient, a more conservative approach was adopted. There are few reported cases of brain involvement with KS and only a minority of these was confirmed histologically.4 Given the imagological features and location, with absence of neurological symptoms, an infectious cause was less likely.5 Primary central nervous system lymphoma is a possible cause, but intraventricular location is rare.6

It is also important to remark the importance of selecting an HAART regimen with high genetic barrier in situations when no genotypic drug-resistance test results are available and immediate HAART is clinically relevant. This is of particular relevance in patients who came from areas where transmission of resistance mutations has a high prevalence.

Figure 1: Left: At admission, multilobulated lesion of the nasal pyramid, with approximately eight centimeters, associated with a lesion of the upper lip, and local invasion of the skin. Right: Marked clinical improvement. After four weeks of HAART and two cycles of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

.