Introduction

POEMS syndrome, also known as osteosclerotic myeloma, is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome associated with an underlying plasma cell disorder.1 First coined by Bardwick,2 in 1980, the acronym stands for some of its main characteristics: polyradiculoneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal plasma cell disorder and skin changes. The diagnosis is often delayed and is a combination of clinical, laboratory and imaging findings.1

This case report illustrates the contribution of imaging studies to the diagnosis of this syndrome.

Case Report

A 69-year-old woman presented to a general practitioner’s consultation with a left supraclavicular lymph node, weight loss and anorexia over the course of 9 months. She also reported paresthesia and numbness of the lower extremities. On physical examination, skin hyperpigmentation was noted.

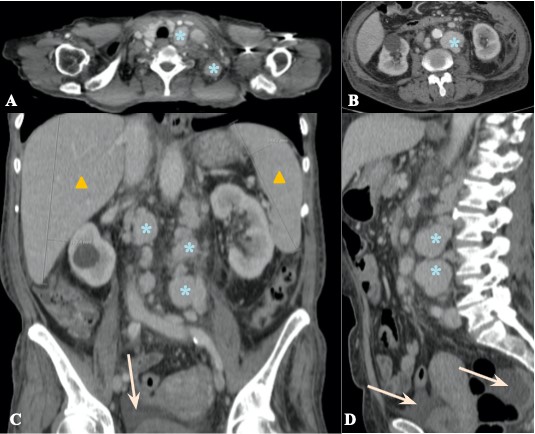

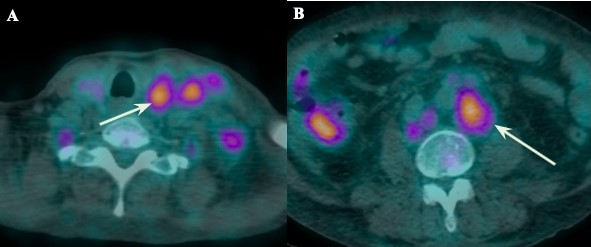

She was referred to consultation with General Surgery and a computed tomography (CT) as well as 18-fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (FDG-PET/CT) of neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvis were ordered. They showed diffuse lymphadenopathy (mostly cervical and retroperitoneal) with homogeneous intense enhancement after contrast administration as well as 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) uptake on FDG-PET/CT, aspects that were characteristic of multicentric Castleman Disease (fig 1 and 2). Associated findings included hepatosplenomegaly and free intraperitoneal fluid (fig 1).

Figure 1: Contrast-enhanced CT scan, soft tissue window (axial plane - A, B, coronal reformatted plane - C, sagittal reformatted plane - D) reveals diffuse lymphadenopathy, predominantly supraclavicular (blue asterisks in A) and retroperitoneal (blue asterisks in B-D) that show enhancement after intravenous contrast administration, findings that were suggestive of multicentric Castleman Disease. There was also hepatosplenomegaly (yellow triangles in C) and mild intraperitoneal fluid (orange arrow in C and D).

Figure 2: 18-fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (FDG-PET/CT) at the level of supraclavicular region (A) and retroperitoneum, just below the renal hilum, (B) reveals 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) uptake by the enlarged lymph nodes, with a SUVmax of 4.45 for the supraclavicular nodes and of 5.44 for the retroperitoneal nodes.

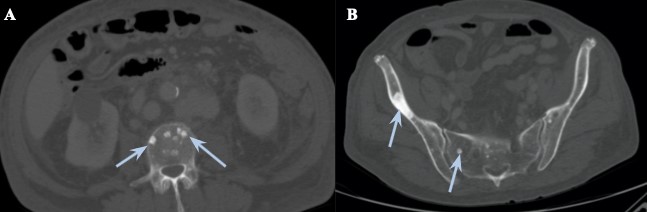

Additionally, there were multiple sclerotic bone lesions spread throughout the vertebrae and the innominate bone (fig 3).

Figure 3: Abdominal-pelvic CT, bone window, at two different levels (A - lumbar vertebrae, at the level of the renal hilum; B - innominate bone) showing diffuse sclerotic punched-out lesions (blue arrows), with the more prominent one in the right ilium.

A decision was made to perform an excisional biopsy of the supraclavicular node. The histology was compatible with Castleman Disease.

After this result, the patient was then admitted to the hospital for further investigation and work-up on this presumed diagnosis of Multicentric Castleman Disease.

Extensive laboratory studies were prescribed, and the main findings were the presence of a monoclonal cell disorder - M protein spike (IgG kappa type) and elevated levels of Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

To further characterize the patient’s paresthesia and numbness, an electromyography of the lower extremities was done and indicated the presence of myopathy with mild neuropathy.

After combining all of these features, a final diagnosis of POEMS Syndrome was established and the patient was referred to Oncology consultation for further treatment.

Following the diagnosis, the patient was first submitted to 6 cycles of chemotherapy with the CyBorDex regimen (cyclophosphamide + bortezomib + dexamethasone), in a total period of 6 months, with good tolerability, having achieved complete response, as proven by the absence of a M protein spike in the subsequent laboratory studies. She was then transferred to another hospital for a hematologic consultation to be evaluated for possible autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), which she underwent 4 months after completing the chemotherapy, roughly 1 year after the diagnosis, with good tolerability and response. Presently, about 5 months post-ASCT, follow-up examinations and consultations have shown no signs of recurrence and absence of relevant clinical symptoms.

Discussion

The major criteria for the diagnosis of POEMS syndrome are the presence of polyradiculoneuropathy, monoclonal plasma cell disorder, Castleman disease, sclerotic bone lesions and elevated VEGF. Only the first two ones are mandatory and only one of the other three is required for the diagnosis.1 In this case, all five criteria were present.

Additionally, there are six minor diagnostic criteria: organomegaly (splenomegaly and hepatomegaly), extravascular volume overload (mild ascites, pleural effusion), skin changes (hyperpigmentation), endocrinopathy, papilledema and thrombocytosis/polycythemia.1 In this case, the first three were also present.

Despite it being a mostly clinical diagnosis, imaging plays a key role in identifying some of the major and minor criteria, namely the presence of Castleman disease/lymphadenopathy, sclerotic bone lesions, organomegaly and extravascular volume overload.2

Sclerotic bone lesions are a hallmark of POEMS syndrome and are better depicted and evaluated on CT, as it is more sensitive and displays more sharp outlines of the lesions, when compared to conventional x-ray.3 Most of these lesions appear as densely sclerotic, sometimes in a plaque-like configuration, but there have been reports of other less frequent appearances, such as lytic with a sclerotic rim or even with a mixed soap-bubble appearance.3,4

FDG-PET/CT has also been proposed as a way to depict these lesions, although the FDG-uptake is variable and it occurs more frequently in lytic lesions.1

Additionally, while evaluating the presence of bone lesions, CT is also useful to identify the other diagnostic criteria, such as extravascular overload (ascites, pleural effusion), Castleman disease and organomegaly.

Castleman disease, in particular, when associated with POEMS Syndrome, typically presents as multicentric disease associated with HHV-8 virus, in which contrast-enhanced CT will show diffuse lymphadenopathy, usually with homogenous enhancement after contrast administration. In multicentric disease associated with HHV-8, it has been reported that the degree of enhancement is less pronounced when compared to unicentric cases of Castleman disease.5

While the potential for FDG-PET/CT in the diagnosis, treatment assessment, and follow-up of CD has not been fully demonstrated, some reports say it can help characterize its extent (unicentric vs multicentric) and help in the evaluation of response treatment. However, other causes of lymphadenopathy can also show 18F-FDG uptake, such as lymphoma or sarcoidosis, which can confound the findings.6

Initially, the diagnosis was presumed to be Multicentric Castleman Disease as represented by the diffuse enhancing lymphadenopathy. However, the presence of diffuse bone sclerotic lesions, organomegaly and mild ascites on imaging studies, combined with the other clinical and laboratory findings, allowed the correct diagnosis of POEMS syndrome to be established.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the radiologist can also help guide the treatment by indicating the extent of the disease and the number of bone lesions, as it directly affects the treatment decision. Patients with an isolated bone lesion can be treated with radiation, whereas patients with disseminated bone marrow involvement with multiple bone lesions, as in this case, are usually treated with systemic therapy. Since there are only a few published randomized clinical trials among patients with POEMS syndrome, treatment recommendations are still only based on limited trial data and case series. The most successful outcomes have been associated with therapy that is directed at treating the underlying plasma cell disorder rather than solely focusing on VEFG with targeted anti-VEFG therapy and this is typically done with alkylator based therapy, such as cyclophosphamide. Other therapeutic options include ASCT, bortezomib and lenalidomide.1

One can also differentiate POEMS syndrome from the Castleman disease variant of POEMS syndrome. The main difference is the latter is not associated with a monoclonal plasma cell disorder or polyneuropathy.1 In terms of treatment, in patients with the Castleman disease variant, anti-IL-6 antibodies, anti-IL-6 receptor antibodies, and rituximab are therapies that should be considered in addition to alkylator and steroid-based therapy.7 In this case, as both were present (monoclonal plasma cell disorder and polyneuropathy), it corresponded to a POEMS syndrome.

Different ways of evaluating the response to therapy have been proposed, due to the multisystemic nature of the disease. One can evaluate changes on the hematologic parameters, with a complete response happening when there is no evidence of monoclonal plasma cell disorder. Similarly, normal post-therapy VEGF levels also suggest a complete response. There is also a role for 18F-FDG-PET/CT in evaluation of the treatment response, in which absence of any FDG uptake would indicate complete response.1

In this case, only the hematologic parameters were taken into consideration, and the patient has not performed any follow-up imaging studies.

In terms of prognosis, in general patients have good progression free survival with modern therapies, with overall 6-year PFS of more than 50%. In those patients who achieve a complete response, the overall PFS is higher (5-year PFS 88%).1

It is important that every radiologist is aware of this syndrome and its diagnostic criteria. Particularly, the presence of diffuse sclerotic bone lesions in association with lymphadenopathy should raise the suspicion of a possible POEMS syndrome and encourage the radiologist to look for other signs/criteria. Additionally, when the diagnosis is suggested, the radiologist can also help guide treatment decisions by characterizing the extent of the bone marrow involvement.