Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Media & Jornalismo

versão impressa ISSN 1645-5681versão On-line ISSN 2183-5462

Media & Jornalismo vol.17 no.30 Lisboa jun. 2017

https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_30_6

ARTIGO

Sisters doing it by themselves: woda in antinu- clear and other protests from the 1980s onwards

Diana SilverI

I Universidade de Coimbra, Faculdade de Letras, 3004-530 Coimbra, Portugal. E-mail: dianasilver@sapo.pt

RESUMO

Por que razão as mulheres optaram por fazer protestos políticos sem homens? Essa escolha tem validade epistemológica e prática para a ação direta no século XXI? O artigo menciona os antecedentes da ação direta de mulheres-apenas em Greenham, no Reino Unido, na década de 1980; Esta manifestação apresentou a NVDA a um público britânico acostumado a formas de protesto com maior deferência, e encorajou muitas mulheres antes heterossexuais a outras formas de sexualidade. O artigo considera as identidades usadas pelas mulheres nessas ações, juntamente com outras identidades que não surgiram. São discursivamente analisados dois manifestos, de Greenham em 1981 e de ações em 2016, que mostram um afastamento da antiga versão da mulher como pacifista, materna e “vulnerável”. Por enquanto, a guerra nuclear foi ultrapassada por uma série de ameaças ainda maiores, mas todas elas exigem respostas além das urnas, com NVDA criativas e feministas continuando a fornecer um modelo útil.

Palavras-chave: Manifestações feministas; Ação direta não violenta; Armas antinucleares; Campos de paz; Greenham Common

ABSTRACT

Why have women chosen to conduct political protests without men? Does this choice have epistemological and practical validity for direct action in the 21st century? The paper mentions the background of the women-only direct action at Greenham, UK in the 1980s; this introduced NVDA to a British public accustomed to more deferential modes of protest, as well as encouraging many previously straight women towards other forms of sexuality. The identities used by women in such actions are considered, along with some other identities that were not on offer. The discourse of two manifestos is analysed, from Greenham in 1981 and from actions in 2016, showing a move away from the earlier peace-loving, maternal, ‘vulnerable’ woman. For now, nuclear war has been overtaken by a host of even greater threats, but all demand responses beyond the ballot box, with creative, feminist NVDA continuing to provide a useful model.

Keywords: Feminist protest; non-violent direct action; anti-nuclear weapons; peace camps; Greenham Common

Introduction

We constitute identities – including our own – in and through our political practice. (Menon 2004, 233)

Why have women chosen to conduct political protests without men, and does this choice have epistemological and practical validity for direct action in the 21st century? - these are the questions that this study attempts to answer. I shall begin by defining NVDA (non-violent direct action) and WODA (women-only direct action), outlining briefly my personal interest in the topic, before considering what identities were available for women in such actions, taking examples from the antinuclear peace camp at Greenham Common, UK, in the 1980s; finally I compare these paradigms with the discourse of two manifestos, from current actions and from Greenham.

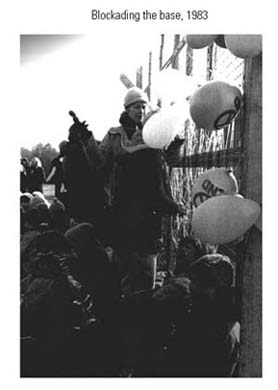

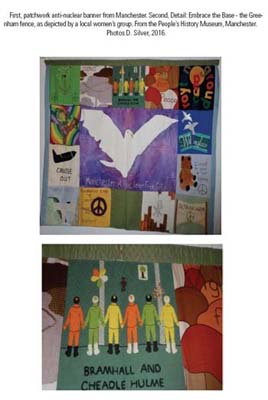

My interest in this topic stems from my own involvement with the Greenham camp in the 1980s. This was a time when Margaret Thatcher’s government, elected in 1979, was transforming British politics, economy and society – forever, as we can now see. While British manufacturing and energy industries were being closed down in the name of global efficiency, the cold war industries of armaments and military forces thrived, in alliance with Britain’s nuclear partner, Reagan’s USA. I and some of my friends found it hard to see all this happening; we had ‘discovered’ feminism through women-only consciousness-raising groups, so to act in some way together with other women seemed natural and right. “People were looking for a focus for their anxieties, and Greenham was it” (Tunnicliffe 2016). So I went down from Manchester to Greenham for special actions such as ‘Embrace the Base’, camped there overnight, and formed part of a campaigning group in Manchester that held demonstrations in the city, raised money for camp supplies, and organized transport to related antinuclear actions (see photographs of actions, below). I shall give more background to the peace camp and its activities below.

Non-violent direct action (NVDA)

Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. (Martin Luther King, 1963)

According to Vogele & Bond, NVDA

“has certain characteristics that set it apart from what might be called ‘routine’, ‘institutional’, or ‘normal’ politics. The key feature […] is the indeterminacy of its outcome, owing to the fact that no rules, norms, or procedures prescribe the outcome.” (in Powers & Vogele (eds.) 1997, 365)

It is different, therefore, from rights-based approaches that use lobbying by legal or political representatives (Abrams 2007, 853). It is particularly appropriate for women’s issues and actions because, according to the Indian feminist Nivedita Menon, democracy does not work for women: we cannot

“address the operation of hegemony in the language of legal discourse”, since “the subject is yet to be made into an autonomous agent”, for “agency is both constituted and subverted by existing structures of power” (Menon 2004, 208-209, 216).

So, instead of lobbying and trying to influence power, there is “engaged critique or resistance” (Abrams 2007, 853). According to the action group UK Feminista, NVDA

“is a powerful campaigning method. […] essentially it involves disrupting or even stopping an injustice. In doing this, activists can expose a problem and highlight an alternative. [It is] DIRECT: During the action, activists themselves make the change directly, rather than asking someone else – such as a politician – to act on their behalf [and it is] NON VIOLENT: […] an active form of resistance which is based on a commitment to end violence and injustice without committing further violence”. (UK Feminista 2013)

It “aims at achieving immediate results, whether visibility, debate or change, through often controversial forms of intervention at the local level”, using actions such as “camps, street parties, [...] sabotage, die-ins, kiss-ins, gatherings and blockades” (Santos 2013, 152), going naked at the World Social Forum (Sutton 2007), or even protesting in your pink underwear (with peace-dove patterns) outside the US Capitol (Abrams 2007, 865). It has been used in support of innumerable issues such as Occupy (Wall Street etc.), Greenpeace and animal right campaigns, and in political protests such as in Tahrir Square and Syntagma Square; in Portugal it was instrumental in the revolution of April 1974, and its use is becoming ever more widespread, given the general sense of disillusionment with the democratic political process, especially among young people. There is always a danger that such methods may be employed by demagogues and dictators as well as by the subaltern and silenced; but when standard processes have been weakened to the point of bankruptcy by the demands of global capital, what else is left for us to do?

The Greenham Common peace camp

Officially an RAF base, as it had been during most of the 2nd World War, and once (as its name shows) common public land, Greenham Common was leased by the British Ministry of Defence to the US air force. As part of NATO’s anti-communist cold war strategy, from 1983 scores of Cruise missiles armed with nuclear warheads were stationed there and were taken out for practice manoeuvres (such decisions, being matters of ‘national security’ were not presented to Parliament, of course). Hearing about the proposed siting of nuclear weapons, some Welsh women involved in anti-nuclear campaigns walked the 180 kms there from Wales in 1981, and decided to stay and camp (Liddington 1989, 222-227), at a time when camping as a means of protest was very new (Rootes 2003, 140). Numbers of protestors grew, and camps were set up at all the main gates to the base. In 1982 the decision was taken that the Greenham camps should be women only.

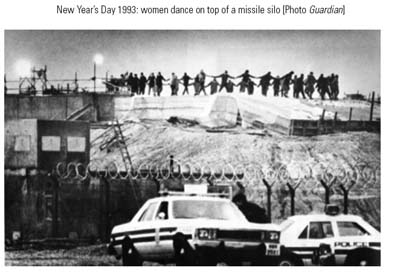

Protesting at Greenham involved a lot more than sitting in a tent in the rain. Campers had to endure repeated, sometimes daily, evictions and arrests. Actions, many of them creative and all illegal by national or local laws, and attracting many thousands of women, included blocking the gates, decorating and cutting the fences, invading the base, dancing on the missile silos, and, in 1982 ‘Embrace the Base’, when 30,000 women (including myself) formed a human chain surrounding the 14.5 kms of the perimeter. Some women camped there for years, others visited for a day of two, camped overnight, and/or participated in particular protest events. Associated actions were held around the country, such as pickets at associated sites, camps at other bases (e.g. the nuclear submarine base at Faslane in Scotland), demonstrations throughout UK (see photo from Manchester, below), and collecting money to support the camp (for waterproof boots, tents, etc.)

The key to the ‘success’ of protests is attracting media attention, for which they must be “big, radical and innovative” (Della Porta 2003, 112), which Greenham certainly was. However, actions there in fact attracted considerable hostility, not only in the mainstream press but even within the peace movement (Roseneil 1995, 169-170). Some of this hostility was related to the identities being eagerly adopted or constructed at the camp and presented to the world by Greenham women. Some of these images were and still are controversial, as we shall see below.

Potential paradigms for the female-identifying antiwar protester

[...] a tendency in antinuclear campaigning to define women in terms of their maternal capacity, associated with peaceability( and a transcendent moralism), while yoking men and masculinity to a predisposition to war and warmongering (and a strategic mindset) (Eschle 2012, 1)

Women now have “a wider repertoire of images and narratives to describe their ‘gendered lives’” (Abrams 2007, 857). According to Eschle (2012, 2), the chief task of the scholar ... should be to destabilize apparent certainties about sex and gender ... rather than reinforce existing power relations”, and we can indeed see below that some of these identities, derived from cultural feminism, are exclusive, essentialist, normative, limiting, or simply false. Here I shall list briefly some of these paradigms, as available at Greenham, together with their possible contestations.

Maternalist (Motherist). This essentially pro-life paradigm assumes that women are inherently antiwar because they can give birth, and can lose sons or husbands in wars. This image, with its stress on women’s suffering and mourning, can alienate non-mothers. De Beauvoir wrote that “Women should desire peace as human beings... Being encouraged to be pacifists in the name of motherhood […] is just a ruse by men”; nevertheless, as Roseneil says (1995, 4), this paradigm “is grounded in the material reality of many women’s lives”.

Mystical. According to this dualistic vision, ‘woman’ has inherent connections with ‘Earth’, with ‘Nature’, over which ‘man’ has exerted dominance. Such a magical, ‘goddess’-related identity means nothing to many women, though it is powerful to a few. According to Rosen (2013, 2), “Traditions inherited - or newly invented – were used to glorify women’s magical healing powers”; though easy to parody, this paradigm certainly gives scope for creativity.

Peace-loving. In this biologically and/or culturally deterministic paradigm, women are seen as inherently less aggressive than men: manhood is naturally pathological, or corrupted by patriarchy. But it was also used strategically as part of the women-only decision at Greenham in 1982, as it was thought that police would behave less violently if they were confronted by ‘peaceful’ women rather than by potentially aggressive men (Roseneil 1995, 40).

Morally superior. Given the long-lasting “normative idea of women as pure and selfless” (Burgin 2012, 20), it is woman’s responsibility to take over control (of Earth? of the Peace Movement?) from man. However, such a highly dubious, essentialist and deterministic view of women has in fact frequently led only to their further exploitation.

Co-operative. This was a key justification for the women-only decision at Greenham. Men, it was said, are inherently competitive among themselves, and tend to take over the lead in mixed-sex activities. This had been seen in the 1960s in the anti-Vietnam war campaigns - indeed it was women activists’ experience then that was instrumental in the rise of second-wave feminism. This paradigm, as expressed in the essentially cooperative nature of the Greenham organization, was something that attracted many women, who said they would not have gone to Greenham if it had not been women-only (Roseneil 1995, 55), something my own Greenham support group certainly agreed with.

Creative. Here women are seen as adept at using their artistic creativity, as well as their craft skills (see p. 97), in constructing powerful images in and about their actions, such as dancing on top of the missile silos (see p.98) , or using traditional imagery for women’s creativity, such as weaving and webs (see p. 96). The camps became “laboratories of innovation”, where new arrangements of bodies and objects “re-imagined feminist subjectivities and reoriented the meanings and uses of technologies” (Feigenbaum 2015, 9). For Donna Haraway in typically arcane mode, Greenham women were her archetypal cyborgs, post-modern, post-industrial, science-fictional, in a land of

“Floating signifiers moving in pickup trucks across Europe, blocked more effectively by the witch-weavings of the displaced and so unnatural Greenham women, who read cyborg webs of power so very well, than by the militant labor of older masculinist politics” (Haraway 1991, 154).

(The ‘floating signifiers’ here are the all too solid and deadly missiles, of course).

Finally, there are some crucial paradigms, one set being very much present at Greenham, the other notable for its absence:

Lesbian Feminist. At Greenham it would anyway have been impossible to maintain the standards of physical appearance expected of a heterosexual woman of the early 1980s. Rather, conditions and decisions meant that “Women deliberately presented themselves as outside conventional heterosexual femininity”. But beyond appearance, “as women disengaged from dominant constructions […] they also saw possibilities of new sexual identities” (Roseneil 1995, 161-162).

Lesbians were attracted to go to Greenham, while some other campers rejected their own previously assumed heterosexuality and began to live openly with other women. However, even lesbian monogamy was questioned: “the couples who built benders on “monogamy mountain” rather than sleeping closer to the fire and the heart of the camp in single person or communal benders were [...] teased” (Roseneil 2012, 9). It was a place of discovery, which left many Greenham women changed for good.

Paradigms that were not on offer:

Black. There were very few black women at Greenham, at least before 1987, nor were there many in the British peace movement as a whole. Greenham women recognized this racism, but found it difficult to counter.

Disabled. Admittedly, Greenham’s terrain and actions would have presented great difficulties for disabled women, but in fact disability does not seem to have been on the agenda at all. I have found hardly any mentions and only one photo of a disabled woman (see below).

Paradigms as seen in two examples of campaigning texts, 1981 and 2016

These two pieces, both informational texts addressed to the media and the public, and separated by 35 years, differ in the target of their protests. In A, it is the nuclear weapons we have so far discussed, whereas the current text, B, attacks cuts to domestic violence services. What I find most interesting, however, is the change of paradigms.

A. From Women for Life on Earth, Press Release, July 1981: this was intended to attract protesters to the initial walk from Wales to Greenham.

Most women work hard at caring for other people – bearing and nourishing children, caring for sick or elderly relatives, and many work in the ‘caring’ professions. Women invest their work in people – and feel a special responsibility to offer them a future – not a waste land of a world and a lingering death. Through the effects of radiation on the unborn and very young children, women are uniquely vulnerable in nuclear war.

Women bear the weight of cuts in public expenditure – fewer social services, less provision for the elderly and infirm, cuts affecting schools.

We can see clearly, through the lexis, that the paradigms in operation here, seen as important by the original Greenham women, are the maternalist as well as perhaps the peace-loving and morally superior. It is assumed that ‘most women’ do these ‘caring’ tasks. There is an essentialist assumption that only women, rather than men, are concerned about nuclear destruction and a ‘lingering death’; ‘uniquely vulnerable’ even uses the image of women as weak and passive.

B. From Sisters Uncut (UK), Feministo, 2016. (“Taking direct action for domestic violence services”) – see photo below.

We are Sisters Uncut. We stand united with all self-defining women who live under the threat of domestic violence, and those who experience violence in their daily lives. We stand against the life-threatening cuts to domestic violence services. We stand against austerity.

In the UK, two women a week on average are killed at the hands of a partner or ex-partner. The cuts make it harder for women to leave dangerous relationships and live safely.

Safety is not a privilege. Access to justice cannot become a luxury. Austerity cuts are ideological but cuts to domestic violence services are fatal.

Every woman’s experience is specific to her; as intersectional feminists we understand that a woman’s individual experience of violence is affected by race, class, disability, sexuality and immigration status.

Doors are being slammed on women fleeing violence. Refuges are being shut down, legal aid has been cut, social housing is scarce and private rents are extortionate.

What’s more, local councils are selling out contracts to services who are running them on a shoestring – putting the safety of survivors at risk and deteriorating the working conditions for those who work with abused women.

To those in power, our message is this: your cuts are sexist, your cuts are dangerous, and you think that you can get away with them because you have targeted the people who you perceive as powerless.

We are those people, we are women, we will not be silenced. We stand united and fight together, and together we will win.

The discourse here, polemical and antagonistic in tone and inspirational in intent, is more complex than in text A. I have indicated specific elements as follows:

Underlined text: these are the ‘we’, the agitators, the activists. The agenda and those setting it are identified, assuming a unified entity of protesters and ‘victims’ (though of course this last word is never used; instead we have ‘those who experience domestic violence’ and the empowering ‘those you perceive as powerless’). The paradigm here is very far from the maternalist and mystical. It is certainly feminist and potentially lesbian (paragraph 4).

Double underlined text: the organisation’s intersectionality (not a concern we would have been likely to find in 1981, as we have seen). Here, ‘Sisters’ is not an unthinkingly inclusive term, as it may often have been in the second wave of feminism. Inclusion of transsexual women is also seen in the first paragraph (“self-defining women”), while current political concerns are included (“immigration status”).

Italics: the ‘you’ who are being addressed. Though the text is ostensibly directed at politicians, it is hard to imagine them being radically shaken in their determination to save money at local level. The text is aimed rather more at onlookers of Sisters Uncut’s street protests, and, like text A, at the media.

These texts show a move away from the peace-loving, maternal, caring, ‘vulnerable’ woman of 1981: the Sisters in text B present themselves as considerably more combative, confrontational and political. Of course not all Greenham women, certainly not all those who settled in or came to the camp after 1981, would have subscribed to the kind of publicity disseminated in text A. And we must remember that not only are the causes different, but the kind of actions being publicised are different too – a long march, over many days, often in rural areas, as opposed to a series of rapid, highly mediatised action in central London.

The political is personal and vice versa: WODA today, and the beneficial liminality of Greenham

In the liminal space of this women’s community, which was literally right up against the fences of patriarchal militarism and at the same time constituted a prefigurative, utopian world apart, radically counter-normative ways of being and living were forged (Roseneil 2012, 8).

The Greenham Common camp became women-only and became increasingly feminist in organisation, rhetoric and ideology after it was founded in 1981. Men were excluded from 1982 onwards, because:

Greenham women felt safer in a space without men-they saw men as more prone to slide into violence (there had been examples of this at the beginning), it was no longer unusual to do so: women-only activities were crucial to second-wave feminism (consciousness-raising groups, self-help therapy groups, etc. ), and because women wanted to present an alternative to male-dominated military-political power structures, which favoured nuclear weapons.

But to what extent are these conditions applicable today? We have seen that some women, such as Sisters Uncut and UK Feminista, consider WODA as still relevant for their campaigns.

The Greenham Common camp meant that women were “Displacing themselves, and relocating themselves into a new environment in which new ways of thinking and being became possible” (Roseneil 1995, 143), (so they became “dissassembled and reassembled”- like Haraway’s cyborgs, perhaps); it introduced many straight women to other forms of sexuality. It also introduced NVDA to a public “whose accustomed political repertoire was almost wholly conventional and apparently deferential” (Rootes 2003, 140). Above all, its creative approach has been deeply influential in many other campaigns.

Nuclear war is no longer the supreme threat it was, largely because it has been overtaken by a host of even greater threats - financial, social, environmental and political. All of these demand responses beyond the ballot box, and for such responses, feminist NVDA continues to provide one useful model. But do these responses have to be single-sex? It may depend on how men behave – if they are now truly able to act as brothers to the sisters, rather than as self-appointed officers in a rowdy army. It must surely depend on how woman-focused the issue is (see Sisters Uncut’s actions against cuts in domestic violence provision). But the actions should have the determination, creativity and sheer staying power shown over the years by the women of Greenham.

Bibliography

Abrams, Kathryn (2007.) “Women and Antiwar protest: Rearticulating Gender and Citizenship” Boston University Law Review 87, 849-882. Consulted 27/4/2016 at http://www.bu.edu/law/journals-archive/bulr/documents/abrams.pdf [ Links ]

Burgin, Say (2012) “Understanding Antiwar Activism as a Gendering Activity”. Journal of International Women’s Studies 13 (6), 18-31 [ Links ]

Della Porta, Donatella (2003) “Social Movements and Democracy at the Turn of the Millennium” in Ibarrra, Pedro (ed.) Social Movements and Democracy. London: Palgrave Macmillan [ Links ]

Eschle, Catherine (2012) “Gender and the Subject of (Anti)Nuclear Politics: Revisiting Women’s Campaigning against the Bomb”. International Studies Quarterly 2012, pp. 1-12 [ Links ]

Feigenbaum, Anna (2015) “From Cyborg feminism to Drone Feminism: Remembering Women’s Anti-nuclear Activisms”. Feminist Theory 16 (3), 265-288. Consulted 4/5/2016 at http://wwww.eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/22662/4/Feigenbaum_Final_AF_edits_28_July_.pdf [ Links ]

Haraway, Donna (1991) Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: the Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge [ Links ]

Liddington, Jill (1989) The Road to Greenham: Feminism and Anti-Militarism in Britain since 1820. New York. Syracuse University Press [ Links ]

Menon, Nivedita (2004) Recovering Subversion: Feminist Politics beyond the Law. Urbana: Permanent Black [ Links ]

Powers, Roger & Vogele, William (eds.) (1997) Protest, Power, and Change: an Encyclopedia of Nonviolent Action from ACT-UP to Womens’ Suffrage. New York: Garland [ Links ]

Rootes, Christopher (2003) “The Resurgence of Protest and the Revitalization of Democracy in Britain” in Ibarrra, Pedro (ed.) Social Movements and Democracy. London: Palgrave Macmillan [ Links ]

Rosen, Ruth (2013) “Woman and the language of peace protest”. 50.50, 2013. Consulted 28/4/2016 at https://www.opendemocracy.net/5050/ruth-rosen/women-and-language-of-peace-protest [ Links ]

Roseneil, Sasha (1995) Disarming Patriarchy: Feminism and Political Action at Greenham. Buckingham: Open University Press [ Links ]

Roseneil, Sasha (2012) “Queering home and family in the 1980s: the Greenham Common Womens Peace Camp”. In: Queer Homes, Queer Families: A History and Policy Debate, 17 Dec 2012, British Library, London. (Unpub.) Consulted 8/6/2016 at http://www.eprints.bbk.ac.uk/7874/

Santos, Ana Cristina (2013) Social Movements and Sexual Citizenship in Southern Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan [ Links ]

Sisters Uncut (2016) Feministo. Consulted 29/4/2016 at http://www.sistersuncut.org/feministo/ [ Links ]

Sutton, Barbara (2007) “Naked Protest: Memories of Bodies and Resistance at the World Social Forum,” Journal of International Women’s Studies 8 (3), 139-148 [ Links ]

Tunnicliffe, Anne (2016) “People were looking for a focus for their anxieties, and Greenham was it”. The Guardian, 16 May [ Links ]

UK Feminista (2013) Action Toolkit: How to use Nonviolent Direct Action. Consulted 2/5/2015 at http://www.ukfeminista.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/NVDA-guide.pdf [ Links ]

Artigo por convite/Article by invitation

Diana Silver – É detentora de um M Phil em literatura inglesa medieval pela Universidade de Newcastle e um M Ed em ensino de línguas pela Universidade de Manchester. Foi professora de Inglês nos programas de graduação e mestrado na Universidade de Coimbra até 2015. Antes, lecionou escolas e universidades da Grã-Bretanha (Newcastle e Salford), Índia (Mumbai) e China (Wuhan). Desde 2015 é doutoranda em Estudos Feministas na Universidade de Coimbra.