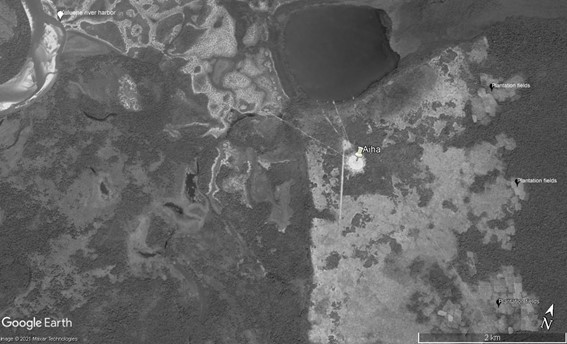

This paper examines some of the implications of a process of rapprochement of the Kalapalo in relation to the “world of white people”.1 The Kalapalo are an indigenous people speaking a variant of karib language, in the Upper Xingu region, Brazil (figure 1). The focus of this analysis is mainly on the opening of a road connecting Aiha village, located on the right bank of the Culuene river (one of the main tributaries of the Xingu river) to Querência, a nearby city in Mato Grosso, and the creation of an internet connection point in the same village. Both processes are directly related to the expansion of money flow in the village, mainly through social security policies (like pensions) and cash transfer, as was the case of Bolsa Família,2 and have been producing significant changes in the daily life of the village since mid-2018. The argument is that these elements - money, the road and the internet - establish new spatiotemporal connections, bringing together territories and people previously unconnected. This creates an expanded notion of territory, which now includes new spaces and relations and expands far beyond the boundaries of the Xingu Indigenous Territory (TIX).

The issues discussed here are based on extensive research with the Kalapalo of Aiha, distributed in several stays in the village between 2006 and 2015, in addition to conversations at other times and spaces (in cities or through social networks). There has also been access to the minutes of the governance meetings (theme to be presented below) held between 2017 and 2019, where the opening of roads constituted the agendas.3 Before proceeding with the argument, however, I present three ethnographic situations that will help to better understand the context.

* * *

In the Upper Xingu villages, illustrious dead and their closest relatives (parents, children, and siblings) should ideally be honoured with a funeral ritual, with the participation of guests from all ethnic groups living in the region. The ritual usually takes place in some of the so considered “main villages” (where many people live, around some “acknowledged” chief), in the same place where the dead are to be buried. However, with the fragmentation of Kalapalo villages over the last 20 years (currently comprising nine settlements, Aiha being the main one) exacerbated by the logistical difficulties of transport, burials cannot always be carried out as desired. The daughter of the main Aiha chief’s oldest sister passed away in 2014 in the small village located next to the local technical coordination of Kuluene, on the south bank of the TIX. Feeling very sad, the family was in a hurry to bury the body, but they had no fuel to transport the body by river to Aiha, where they would like her to be buried. As a result, the deceased was buried in the same village where she died and her close relatives from Aiha went there to weep over her grave. There was no celebration in her honour.

* * *

The year was 2015, the peak of the rainy season. Unlike the dry season, part of the road that cuts through the south of the TIX, allowing access to villages bordering the Kuluene river, was flooded and with restricted traffic. Consequently, a long section of the route between Canarana (the main city in the region in commercial terms and the most accessed by the Kalapalo at that time) and the Aiha village needed to be made by the river Culuene. Despite the logistical difficulties, after raising the necessary money, one of the main fighters of Aiha went to Canarana to buy a highly desired motorcycle, which would be used to access other villages to participate in the intercommunity festivals to come, right at the beginning of the dry season. He came back piloting the motorcycle, but had to carry it on one boat, to get around the more flooded stretch of road. With strong winds and a lot of rain, the boat flipped halfway through. The people on board were able to swim to the shore, but the motorcycle and all his belongings sank to the bottom of the river. The motorcycle was never recovered.

* * *

Between 2008 and mid-2015, Aiha village lacked a construction considered suitable for the activities of the school that operates in the village. After the previous construction, made with a wooden structure and a straw roof, was demolished due to the precarious conditions, a new temporary structure was built, with the mobilization of the village’s teachers. However, this structure was not yet considered adequate, as it was composed of a single setting, which needed to be shared by more than one class at the same time. There were many promises from the municipal and state administrations that material would be sent for the construction of a new school building in the village. Whether due to lack of conditions for transportation, or lack of effective mobilization of the administrators, the new wooden school with a fibre cement roof was only built in mid-2015, using materials and manpower made available by the State Secretariat of Education of the state of Mato Grosso. This new construction allowed the expansion of existing classes and the creation of new high school classes. The new building has three separate classrooms, as well as a space for administrative activities and storage of material.

* * *

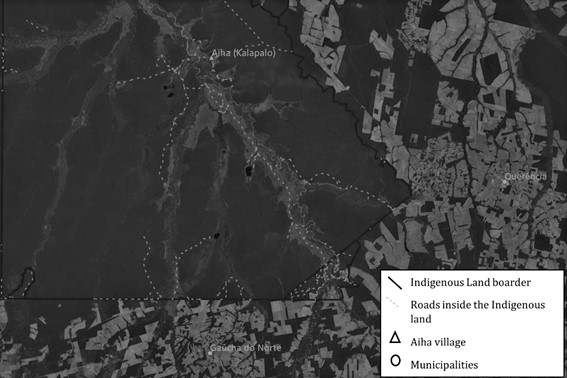

These three reports are some of the many quite recent events that have caused the Kalapalo of Aiha to mobilize for the opening of the road that today links the village to the eastern boundary of TIX, providing easy access for the population of this and other villages to the town of Querência. What I call roads here are dirt tracks, open in the middle of the woods or in the countryside, which connect the upper-xinguan villages to the most diverse locations, within the TIX, regardless of their size or extension. The first discussions I followed about the opening of Aiha’s road took place still in 2014, and in mid-2018 the route was completed, with a total length of about 40 km (figure 2), all of which can be covered with cars or small trucks and vans.

Source: The roads layout was kindly provided by ISA

Figure 2 Roads inside the Xingu indigenous territory

Roads are desired for their potential to create connections and relationships with distant spaces and people (be they Xinguanos, non-Xinguanos or non-indigenous). By creating new connections, they contribute to the expansion of people’s “intersubjective spaces-times” (Munn 1986) and to the shaping of a “territory” (cf.Gallois 2004)4 that is in a constant process of mutation. I propose that, as Calavia-Sáez has pointed out about the Yaminawa, it should be possible to think of Kalapalo territory as something that is constantly created and recreated using established social relations (Calavia-Sáez 2015: 272), in which case roads and waterways play a central role. But the new relationships created with non-indigenous people, at the same time as they are desired, are also feared, since these people mostly reveal themselves to be selfish, greedy, and potentially responsible for illness and death. The solution that seems to have been found by the Kalapalo, in this sense, is the exercise of very particular notions of autonomy, protagonism and self-determination 5 that point to attempts of creating and controlling what can be considered a “good distance” from whites and their spaces.

To develop this discussion, I start by making a presentation of the Kalapalo and Aiha, outlining a brief history of the process of opening the road. I then move on to a presentation on the relationship between the Kalapalo and the cities, finally dealing with the importance of the roads in the upper-xinguan context. I conclude with a concise discussion about the theme of the territory in this ethnographic region, pointing to its transformative and aggregating aspect.

Facing “difficulties” 6 and overcoming “needs”: brief history of the Aiha road

The Kalapalo are one of the five Karib-speaking peoples of the Upper Xingu (along with the Kuikuro, Matipu, Nahukwa and Naruvotu). The Kalapalo account for a little over 900 people, distributed among nine villages, spread over the southern portion of the TIX. This region, also known as Upper Xingu, comprises a multi-ethnic socio-cultural complex composed of 11 peoples speaking three of the main South American language groupings (Arawak, Karib and Tupi), in addition to a language considered isolated (the trumai).

Despite the inherent particularities of each group, these peoples share an intense network of circulation of objects, marriages, and a set of regional rituals, forming a multi-ethnic system. In addition to the Upper Xingu, TIX is composed of three other regions: the Lower Xingu, the Middle Xingu and the Eastern Xingu, where six other peoples from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds live.

The first intentions of the inhabitants of Aiha to open the road appeared in sporadic conversations in the centre of the village 7 and developed gradually (figure 3). Still in 2014, some attempts were made to liaise with the farmers around the TIX and with the municipal governments of the region, with a view to obtaining the support that was considered necessary by the Aiha leaderships for the opening of the road. The Kalapalo requested machinery, material, and personnel from the authorities, especially for the construction of the bridges needed to cross the streams that cut the path that was planned for the road. At the same time, informal talks have begun with representatives from other villages who could also benefit from this road, in order to increase support and, consequently, pressure for the road to exist. In early 2015, with the help of a small satellite geolocation device, the first expeditions of villagers were organized to open the picadas (small passages, open in the middle of the woods, where one can only walk) of what the road would be in the future. But it was only in mid-2018, after a series of discussions and meetings involving all the people of TIX, that the road was finally made official and completed.

Since the creation of what was called Xingu Indigenous Park in 1961, the relationship between the peoples living there has been marked by peace, which does not prevent, however, major differences, especially regarding political, economic, and environmental management of the territory. These divergences have become even more evident in recent years, following the promulgation of the National Policy for Territorial and Environmental Management of Indigenous Lands (PNGATI),8 created with the objective of “guaranteeing and promoting the protection, recovery, conservation, and sustainable use of the natural resources of indigenous lands and territories […], respecting [the] socio-cultural autonomy [of the indigenous peoples]” (Brasil 2012: art. 1st). In order to achieve these objectives, the text stipulated the use of two tools, ethnomapsulation and ethno-zoning. These, as far as it is concerned, would provide the basis for the consolidation of the so-called Indigenous Land Territorial and Environmental Management Plans (PGTAs). Built on notions of “autonomy”, “protagonism” and “self-determination”,9 these plans were thought of as “instruments of intercultural dialogue and planning for the territorial and environmental management of Brazilian indigenous lands, prepared by indigenous peoples with support and in dialogue with other partners and the government” (Bavaresco and Menezes 2014: 25-26).

At TIX, since the implementation of PNGATI, the main indigenous non-governmental organization representing the peoples living there, the Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (Xingu Indigenous Land Association - ATIX), in partnership with the indigenous NGO Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), has conducted a series of meetings and workshops involving representatives of the 16 peoples living there, with the aim of training leaders capable of acting in the manner proposed by the policy. As detailed in the TIX Management Plan (ATIX, ISA and Funai 2015: 10), the discussions carried out in this process began in 2009, when the National Indian Foundation (Funai)10 consulted the indigenous peoples about the PNGATI. In the following years, between 2010 and 2012, diagnoses were made, aiming to raise the main problems faced by the peoples who inhabit TIX. Based on these diagnoses, seven priority themes for discussion and action were defined: “culture”, “territory”, “economic alternatives”, “food sovereignty”, “education”, “health”, and “internal infrastructure”. The meetings held in the following years focused on defining proposals to address the problems identified and finally, in 2015, the TIX Management Plan was approved at a general meeting convened by ATIX. The information contained in this document should ideally serve as a guide for future decisions involving each of these issues that directly or indirectly affect the peoples living in the territory. The main leaders of each of the villages participated in these discussions, as well as young people with some educational background, who speak and write in Portuguese, even acting as translators for the leaders during the meetings.

As part of this same process, the representatives of the peoples covered by the territory have defined a decision-making structure, called governança (governance) by them, which is not, therefore, confused with the governance proposed by the PNGATI, although clearly inspired by it. According to the concept of the Xingu peoples, this governance structure “mixes a little of our [read, the xinguano] culture with a little of what we learn from the whites” (ATIX, ISA and Funai 2015: 12) and is divided into three levels: by people, by region (Upper, Middle, Low and East Xingu), and general (uniting all ethnic groups resident in TIX), according to the scope of the subject to be discussed. At the most local level of governance, each people have autonomy to decide how its meetings and decisions should work. Among the Kalapalo there were at least two meetings between the years 2016 and 2017, with the participation of representatives from (almost) all the villages that identify themselves, at some level, as “kalapalo”.11 Their agreement is that decisions should always be consensual, without any vote. This type of decision directly reflects the upper-xinguan political ethos, marked by the idea of non-aggression and self-restraint.12 This does not mean, however, that there are no opposing views and disagreements on the issues discussed, only that such disagreements should not be expressed emphatically in public and collective debates.

The opening of roads within the boundaries of TIX is one of the controversial issues that directly or indirectly affect all residents of the territory. In addition to the discussions and mobilizations held informally by residents and leaders of Aiha, in formal terms the discussion for opening the road began at a local meeting with the participation of representatives of the different Kalapalo villages. At that time, there was a consensus on the proposal to support the opening of a road in Aiha and then the discussion went on to the other levels of governance. The roads were part of the agenda that made up the general meeting held in March 2017, which was attended by representatives of 14 of the 16 peoples who live in TIX. In addition to the request to open the Aiha road, the list attached to the minutes of the meeting (Governança Geral do TIX 2017) included 26 other different requests for roads. The demands covered all four TIX regions, and included roads connecting different villages, roads connecting villages to the boundaries of the territory and roads connecting villages to other pre-existing roads. Each request was detailed by at least one participant of the meeting and there were general but also regionalized rounds of discussion, separating representatives from the four regions. Of the total number of requests made, only six were approved at the end of this meeting: three in the Lower Xingu, two in the Middle and only one - that of Aiha - in the Upper Xingu.

In general, the speeches of the representatives who supported at least some of the roads demanded were based on the “needs” and “difficulties” faced by the different villages. The arguments, as explained in the minutes of that meeting, included the greater facilitation of the construction of health posts and schools in the villages; the possibility of more effective removal of patients in serious condition to the hospitals of the region; the facilitation of travel to multi-community festivals; in addition to the facilitated access to the cities and to social security benefits. However, the large number of requests for opening roads surprised all participants and prompted some negative assessments, causing some of the applicants to even give up their original ideas. The concerns mainly involved the fear of increasing the use of alcohol and other drugs, especially by young people; the fear of undue invasions of the territory by loggers, farmers, fishermen or unauthorized persons; and the growth in the consumption of industrialized foods and the consequent increase in previously non-existent diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension. During the discussion, representatives from each of the TIX regions were asked to indicate which roads should be prioritized. Thus, after a whole day of meeting, with speeches from various leaders pointing out the advantages and disadvantages of opening the roads, highlighting the “needs” and “difficulties” of their own villages, but without any vote at the end, it was defined which routes would be approved. The decision to authorize only six of the routes did not please all participants, even if it was “consensual”. This dissatisfaction is confirmed by the new requests to open roads (re)submitted at subsequent governance meetings.

In Aiha, this movement to seek an approach to the cities by opening a road was also accompanied by mobilizations of young village leaders to create an internet access point in the village school. Implemented by the State Secretariat of Education of Mato Grosso, this point began operating in mid-2018 (almost simultaneously with the opening of the road), at the school’s headquarters, allowing residents there to connect to the world wide web using their own mobile phones, completely spread throughout the village. Through mobile phones, new connections are created, and relationships strengthened, whether through participation in social networks, the possibility of sharing videos and photos more effectively and with greater reach, the possibility of strengthening political links with other villages, peoples or even non-indigenous considered friends or authorities, or the simple possibility of expanding vocabulary and knowledge related to the world of white people.

But this active search for the world of whites is part of a more complex process with more nuances than it might seem at first, if we consider that it happens concomitantly with the discussions about the opening of a federal highway,13 BR-242, to which the Xinguano peoples (including the Kalapalo) are opposed. This project has been generating great dissatisfaction among the residents of the TIX, as the planned route was just over 10 km away from the southern boundary of the territory and the Pequizal do Naruvotu Indigenous Land, annexed to the TIX. The Xinguanos’ opposition to this highway is based on the potential negative impacts that the work and the subsequent increased circulation of vehicles would promote in rivers and forests, in addition to the expected indirect impacts on the quality of life in the villages, with the emergence of possible “farms, villages, bars, increasing cases of alcoholism, drug consumption and prostitution and the intensification of vehicular traffic and the increase of running over animals and people” (Caciques e lideranças do TIX 2019: 1).

In July 2017, a few months after the general meeting of governance mentioned above, when the road routes were approved, an extraordinary general meeting was convened specifically to discuss the opening of the BR-242 highway. At that meeting, the present leaders prepared a letter disavowing the opening of the highway without proper prior consultation and through a process that disregards the protocol of consultation of the peoples of TIX (ATIX 2016). In the same letter, they requested that the planned route be changed, making use of an existing route, which connects the cities of Querência and Canarana, in order to increase the distance between the highway and the limit of TIX and Pequizal do Naruvotu IL.14

On the one hand, the opening of the Aiha road points to a desire to get closer to the cities and the world of white people. But opposition to the highway seems to point in exactly the opposite direction, in an attempt to pull away and distance oneself from the potential dangers presented by a possible extreme approach to this world, full of hazards and seductions. A contradiction which is only apparent, and which exposes local attempts to control the ways in which the relationship with whites should be established. In order to better understand this double movement - of approach on the one hand and the search for distance on the other - I think it is necessary to address two fundamental questions: the reasons that lead the Kalapalo to seek the cities and a discussion about the importance of paths in the landscape and in the constitution of a territory for the upper-xinguans. Let us move on to the first topic.

From village to city: creating and transforming values

There are several reasons why the Kalapalo seek out the cities. In general, they do so to access social and welfare benefits, industrial goods and create and strengthen their networks of relationships with non-indigenous people. In addition, cities also enable people (especially young people) to study and learn Portuguese (despite the existence of a school in the village). In general, they are young men who move to the cities, bringing along wife(s) and children. The women only go out to study while they are single and, in most cases, are sent to live in other villages that have easy access to some town in the region, under the care of close relatives. Parents express a constant concern for their daughters, fearing that they will become pregnant or get married in the cities.

As I have pointed out elsewhere (Novo 2019, 2018), desire is a fundamental concept for understanding this movement toward whites. It is a bodily state that, if not satisfied, “could lead to a general loss of control and its unavoidable consequences” (Novo 2019: 136), which may include the illness and even death of the one who has not had his desire satisfied, especially when it comes to children. “As incomplete human beings, children are more susceptible to illness and ‘soul-abduction’, demanding particular care” (Novo 2019: 136).

The desire fostered by the city is intense and, when it comes to the relationship with the industrialized objects, several characteristics are involved in the evaluations of what is or is not desired and, therefore, considered beautiful-good (hekite). Such evaluations apply to all kinds of objects, clothes and industrialized hammocks, going through glass beads and cotton string, used in the production of ornaments, household appliances, electronic equipment, sports equipment, toys, food…

In order to access the desired objects, however, the Kalapalo must first access the money. The main sources of income in the village today are, apart from salaries (received by a small minority of professionals hired in the village as teachers or indigenous health and sanitation agents), social benefits from social security policies (retirement or maternity pay), or cash transfer policies, such as Bolsa Família. These benefits guarantee the income of most of the houses in the village, which allows people to fulfil their desires and those of their close relatives.

But the approach to the cities, although much desired, is also feared, as pointed out in the oppositions shown both to the opening of a large number of roads within the TIX and the highway, to the south of the territory. Cities are at the same time perceived as spaces of abundance, where you have everything you want, whenever you want, and as a space of poverty, suffering and constant danger. It is quite common to hear assessments that say that in the city, “when you are hungry you just go to the market and get it. In the village, sometimes there is no fish. So, you still have to fetch it, prepare it. It’s hard”. At the same time, the general view that people living in the village have of the indigenous people who are in town is that they are jatsi, “poor people”, who need to go on “begging for change”, because they never have enough money to maintain themselves comfortably.

Frequently, people complain about the time they stay in the city - be it days, or months - saying that “it’s very difficult to stay there, it’s not like the village”, “here [in the village] there’s lots of food and it’s all free”, “in the city you have to pay for everything”, or stressing all the suffering they face when they stay for long periods in urban environments. The scenario is always more difficult when they take their young children with them, as this makes the journey significantly more expensive. The children have a much lower capacity to contain their desires and “want to eat all the time, keep asking for ice cream and soft drinks”, requests that cannot be denied.

Even if they have financial resources from the cash transfer policies, young people who move to the cities to study, especially when they carry wives and children along, are forced to work to support themselves while studying. This situation also makes the experience more difficult, for both men - who work all day and still study at night - and women - who spend all day at home alone, taking care of their children. The city is perceived by those in the village as a space of much solitude and reduced sociability (at least in theory), which can cause nostalgia and sadness - and therefore illness - in people. Looking from the village point of view, one has the impression that far from the networks of kinship, the life of these young people would be of much suffering and white-like, with no one to share food nor whom to count on in times of difficulty. The inexistence of networks of sharing - of kinship, therefore - provides great suffering and, in more extreme cases, leads to sickness and death, this being one of the main fears when the Kalapalo deal with the possibility of “becoming white”. A boy who took a technical nursing course and returned to the village told me of his plans to continue his studies in the city, taking some higher education. I asked him if it would not be too difficult, thinking about the long stay in the city required in this case and the answer I received was that “suffering is normal”, indicating that the expectation they have to go and live in the city is always to face difficulties.

This theme of suffering associated with staying in the city also appears frequently in the posts of many upper-xinguans I follow on social networks, who claim that “struggle”, “suffering” and “difficulty” are necessary paths to “fulfil their dreams”, that is, to fulfil their desires. Here it is necessary to recover Carlos Fausto’s argument about the value of objects which, as I suggest, can also be extended to the experiences lived in the cities. According to the author, the value of objects - particularly “traditional” objects - for Kuikuro is associated “with the fatigue, the suffering and the difficulty involved in their manufacture” (Fausto 2016: 135). In my experience with the Kalapalo, although these questions are considered in the assessment, they are not definitive criteria to define the value of an object. This criterion, however, seems to give the undergone experiences a much higher value. Thus, when a shaman reports the experience of his formation as a shaman, the narrative focuses largely on the suffering and difficulties of the process. The same is true for young people who live in cities. To some extent, both experiences (of shamans and young people in cities) can be comparable: they are long, suffering-laden processes through which people perceive another world, becoming potential mediators in the relationships they establish with that other world. Not by chance they are two processes that have a direct impact on the bodies of those involved and that allow one to experience (even if temporarily) different affections and diseases and the “expansion of knowledge about other ways and possibilities of Being in the world” (Capiberibe 2018: 72), allowing the expansion of interpersonal spaces-times. However, distinctly from the process of shaman production that does not seem to produce much desire in people (after all, my hosts claim that there are no young people interested in becoming shamans, precisely because of all the difficulties and dangers involved in the process), establishing more or less lasting relationships with the world of whites seems to be a personal project of many people today.

In the Upper Xingu all things have an “owner”, that’s how the Kalapalo - and the other Karib-speaking peoples of the region - translate the term oto. But this translation by itself is somewhat problematic given the fact that, when talking about owners, the Kalapalo (and possibly the other peoples of the region) are dealing with something quite different from the western conceptions that enlighten our ideas about possession and property. In general, this relationship is more related to an idea of care, which can be thought of as extensions of a feeding relationship, in both a literal and metaphorical sense. Thus, they comprise actions that include, but extrapolate, the supply of food (following Costa’s [2013] argumentation), and that compose a picture in which one, or what is possessed, is fed/cared for by its “owner”. “Owners” are also those who can dispose of some object, whether by offering, selling, exchanging, or even destroying/rendering it.

Thus, for the Kalapalo, whites are the true owners of the industrialized objects, and it is their role, ideally, to make them circulate. Since whites are the owners of the desired goods and have shown, over the last decades, some willingness to give them - for example, using objects as a form of attraction of indigenous peoples at the beginning of the “contact” process -, it is up to the Kalapalo to ask for them, encouraging exchange - which is, as far as they are concerned, part of their own ethos (cf.Novo 2018: 38-85). When the requests made have the desired effect (meaning they are accepted) these whites are considered friends (ato) - the way the Kalapalo refer to most of the whites they know and have cordial relations with.

Friendship is a very common type of relationship among the upper-xinguans and involves people of the same sex who exchange things with each other in fairly long-lasting relationships. When it comes to non-indigenous friends, exchange circuits that imply longer periods of indebtedness also serve as a kind of relationship thermometer, indicating that the white person has real intentions of returning to the village and/or keeping the relationship active. It is a form of relationship distinct from that which they establish with whites that are considered “powerful” or representatives of the “government” (“authorities”). In this case, like the Paumari presented by Bonilla (2005), the Kalapalo place themselves in a submissive position, as children in front of their parents (employees in front of their employers, in the case of the Paumari), seeking to extract from those with whom they relate generosity and care, materialized in the offering of money, objects and varied resources. With their friends, on the other hand, the relationship should be more symmetrical and always demands the retribution of the goods offered with other goods.

But the willingness of non-indigenous people to circulate their objects is always very restricted and their selfish and greedy attitudes make them unable “to live correctly among relatives or to produce people as relatives” (Mantovanelli 2016: 220), in the Kalapalo’s perception. That is also why the marriages of upper-xinguan men and women to whites are so poorly appreciated and often emphatically dissuaded. In discussions during the II Meeting of the Kalapalo People there was consensus that “The Kalapalo people do not allow the marriage of both sexes to whites” (Povo Kalapalo 2017). As I was told, this type of marriage is awfully bad because it has a great capacity to “put an end to culture”, since the spouses, in these cases, “do not dance at parties, and do not cut their hair properly”. Marriage is considered a possibility of relationship, therefore, it happens only when it adds new people (and, consequently, their things) to the daily life and ritual of the villages; to marry with a non-indigenous is a possibility only when the person with whom one marries becomes “kalapalo-like”. When, on the contrary, the union leads to the spouses moving to the city or other distant places, this makes it impossible to maintain a frequent relationship with the relatives who remain in the village and causes, in their evaluation, the rupture of the relationship.

From these discussions, one can perceive the complexity and dubiousness of the relations of the Kalapalo with the whites and the cities. If, on the one hand, cities and objects are desired, on the other there is a permanent feeling of fear/dread in relation to whites and their world. But this transit through spaces inhabited by others, potentially dangerous beings, has always been part of the upper-xinguan way of life. The paths that connect worlds and beings and allow them to create relationships and expand their spacetimes have always made up the territory inhabited by them.

A jagged territory

Several studies have pointed out that roads and paths have always played a central role for the Amerindian indigenous peoples, serving as means of interconnection and maintenance of intense exchange networks and circulation of goods, people, rituals.15 In the Upper Xingu, the scenario is not different. Despite the sedentary nature of the process of “xinguanization” of the people living there (Heckenberger 2001), the paths have always played a fundamental role. Looking at the local topography, one can easily observe the presence of a series of paths that depart from the villages, cutting the woods and fields around them, leading to the main fishing spots, the gardens, the ports, the other villages in the region and, currently, also the cities (figure 4). This model of space occupation is not recent, as shown by archaeological research conducted by Heckenberger (2005; Heckenberger et al. 2003). According to this author, by the 15th century the Upper Xingu region was densely populated and distributed in several villages that were ten times the size of today’s. According to Heckenberger, “the villages articulate with the local landscape and with other similar villages in a fairly standardised way […] they distance themselves from each other according to a virtually regular pattern of spacing […] and are interconnected by a complex system of paths, bridges, ports and campsites, which also form an integrated network in the territories of the other villages” (Heckenberger 2001: 32). As well as the large village complexes, the paths that connected them were also quite imposing, and were described by Heckenberger (2005: 118) as “curbed highways of at least ten meters wide”.

The upper-xinguan villages are circular, formed by a patio surrounded by a set of houses. Near the centre of the patio is the “men’s house” (kuakutu), a space where the sets of flutes forbidden to women are kept, as well as some other ritual aids (figure 3). In these villages there is a great concern with the aesthetics of the surroundings and the maintenance of collective spaces such as the patio, the men’s house and the main roads that give access to the village. Thus, besides the space formed by the patio, the houses, and their immediate surroundings, the upper-xinguan villages are also made up of paths, which connect this “centre” to a “periphery”, composed of the gardens, regions of fruit gathering, fishing, etc. Additionally, the Upper Xingu presents a more complex spatial distribution. Because it is a “regional culture”, the people living there have a sociality and ethos that “both promotes and is based on intra- and inter-village interaction, hospitality and adaptation” (Heckenberger 2001: 35). In practical terms, interaction has always been possible - and desirable - precisely because of the existence of roads and paths (whether terrestrial or aquatic); the narratives tell of long journeys that included walking parts, in addition to other segments that were travelled in canoes, following the course of rivers and lakes in the region.

Referring to a process of documentation of one of the ancient territories occupied by the Kalapalo before the creation of the Xingu Indigenous Park, Guerreiro (s.d., highlights in the original) points out as “the [kalapalo] filmmakers intentionally recorded several minutes of pure walking, as an explicit attempt to capture how they move through the land, always walking in line, following an elder leader: ‘That’s how we go from one place to another’ […]. Rather than representing the land statically on a map and time through stories, they tried to actually recreate the movements that characterize it”.

Additionally, it is possible to learn from Xinguano mythology that it was through contact with distant beings (especially with the hyper-beings itseke) that people (kuge) acquired essential cultural goods, such as water, or objects considered valuable, such as uguka, a belt (when used by men) or necklace (when used by women) produced from round plates of the inhu snail (Megalobulimus sp.).16

The Kalapalo ancestors always maintained intense relations with neighbouring peoples, but also with other beings, whether itseke or white, some of them more dangerous and others more willing to establish cordial and peaceful relations. From the everyday experience of the Kalapalo, the relationship with whites is closer to that established with predatory beings than that maintained with beings whose behaviour is more like the ideal behaviour of kuge.

This description raises important elements regarding the notion of territory in the Upper Xingu. As several works have pointed out (Laboratório de Antropologias da T/terra 2017; Gallois 2004; Calavia-Sáez 2015; Vieira, Amoroso and Viegas 2015), the conception of territory for the Amerindian peoples is considerably far from the juridical-legal conception of territories demarcated by borders, transposed on static maps. In the case of the Kalapalo, it seems to make more sense to think of the territory as something closer to the definition of Bonnemaison (1993: 211), to whom “territoriality can […] be much better defined as the social and cultural relations that a group maintains with the web of places and itineraries that make up its territory than as a reference to the usual concepts of biological appropriation and boundary”. From this definition, territories are no longer understood as delimited spaces, but as a complex of paths connecting points, drawing closer to an idea of a network, or what Albert (2007: 584) calls “reticular space”. This definition also allows a more integrated understanding of the processes of opening the road in Aiha and creating an internet access point in the village, since both allow exactly to connect points - physically or virtually. Both forms allow expansions of the spacetime of those who live in the village, creating and strengthening relationships and expanding their territory.

As discussed in the previous section, currently, in addition to connecting different villages, or villages and fishing points or even gardens, the desire of the Kalapalo is to also connect themselves to the surrounding towns. Whether physically or virtually, with roads or the internet, the Kalapalo seek to approach, in their own way, the “world of whites” and their objects and knowledge. The road and the internet are paths that enable, each in its own way, the transit of bodies to other worlds and worlds of others. They allow people to experience different ways of being through the type of clothing worn, the language spoken/written, or the personal names used. And with this, bodies also transform, magnify and add to themselves the new relationships created and experienced. As Horta points out, “what brings the indigenous to the city is not a lack, which if supplied inside the village, will solve the issue and keep them in place. No. The indigenous person goes to the city to do something, to produce a transformation in himself and in the world: this is his desire, and he connects a plurality of elements and perspectives that are not ordered as means and ends, terms and functions, but that hook each other and provoke, in the complexity of these relationships of alterity without conditionals, a productive movement - a desiring machine.” (Horta 2018: 96)

The road and the internet also give the Kalapalo from Aiha a dimension of autonomy: they no longer depend on others to mediate the relations established with the whites, or to watch over their cars and trucks that remained parked in the ports near the roads of other villages. And considering that all spaces have owners - be them human or non-human - the road also allows them to travel less, since the journey is shorter, through spaces of “others” to reach the city, becoming less exposed to looks and envy (both potential sources of illness and even death). And while it allows - and in a way encourages - more frequent visits to the city, the road also allows the Kalapalo of Aiha to stay in the cities for a shorter time. The prolonged stay has always been seen by them as a major problem, both in terms of the expenses created and the prolonged distance from the village’s affairs. The difficulty of traveling to Canarana, associated with the high cost of the trip, often resulted in the need to stay in the city for several days. With the easy access to Querência county, the incursions can be shorter and more precise, even if they are more frequent. From the Kalapalo’s point of view, this change is significant in that, at least in theory, it takes people away from their family less as well as from collective responsibilities in the village, giving them some sense of control over how the relationship with others - in this case, non-indigenous - is established.

This idea of control - and the difficulty of always maintaining it - was made explicit during the pandemic that struck the world in 2020. Afraid of what was to come, and still having a very close memory of other epidemics that killed so many of their own, the Kalapalo decided, as soon as the first cases in Brazil appeared, to “lock themselves” in their villages, avoiding as much as possible contact with people coming from the cities. At that moment, the road proved to be a hindrance. As soon as the decision to close was made, the Kalapalo from Aiha were ready to restrict road traffic using a large log blocking the way. However, a few days later they saw the need to reinforce the barrier, building a wooden gate closed with a lock that needed to be changed a few times, after being broken by people who remained in transit among towns and villages without proper permits.17

The rejection of the opening of the federal highway close to the boundary of its territory is based on this same perception of control over how the relationship with others is established - or should be established. Although the desire for the world of whites is explicit and gains strength in the village, somehow the Kalapalo realize that this has been done according to their own conditions, their own ways. From the moment a highway cuts into their territories (even if outside the boundaries of TIX), they would find themselves victims of a type of forced and potentially dangerous relationship, including several unknown and unwanted people and situations.

Expanded territories

The Xingu Indigenous Park was the first indigenous territory demarcated in Brazil, in 1961. Since its creation, the demarcated territory has already suffered alterations, which included the dismemberment of the region that would become the Capoto/Jarina Indigenous Land, with the creation of the BR-80 highway (now MT-322), in 1971. A few years later, in 1978, Federal Decree no. 82,263 changed the name of the Xingu National Park to Xingu Indigenous Park. In the last ten years, with the discussions about the management of the territory provided by the PNGATI, the Xinguanos started to use the term indigenous territory, instead of continuing to use park (the official nomination of the demarcated land). In this case, the idea of a territory broadens the spatial dimension of the demarcated land, as it adds three other adjacent demarcated lands to the Xingu Park: Wawi, Batovi and Pequizal do Naruvotu.

This expanded concept of territory can also be seen in the processes of opening roads within TIX, as I pointed out throughout the text. But this is not a territorial expansion that aims to incorporate new spaces into the demarcated territory. This expansion is related to an idea of traffic, of circulation - through the city or other territories with other owners - and, in this sense, linked to the creation and establishment of interpersonal relationships. This circulation, in turn, reinforces the impossibility of a rigid distinction between “village Indians” and “city Indians”, as the current Brazilian indigenous policy intends. Although they are often in transit through the cities, the Kalapalo always express their desire and the importance of returning to the village, to their relatives and to the planting care tasks. Therefore, attempts to approach non-indigenous people do not represent a process of “becoming whites” or incorporating others, but exactly of allowing temporary experimentation of other ways of living and relating, expanding repertoires and (re)creating relationships.

Considering the above, we can see that the Kalapalo’s approaches to cities and the world of whites should not be treated only as a “break with the ‘traditional worldview’ of the Indigenous people” (Miller 2005: 190), creating both continuities and discontinuities throughout this process. If opening paths is one of the “traditional” ways for the Kalapalo to deal with the relationship with others (from the closest, such as the nearby upper-xinguan villages, to the farthest, such as the hyper-beings/spirits itseke, and now white people), cities and whites seem to set new challenges and effects that are not always expected or even well evaluated. The possibilities of effective relationships with otherness are always subject to experimentation and reformulation, according to the way in which others also behave in response to kuge/people’s actions. White people were, from the beginning, classified by the upper-xinguans as “others” who, in some moments, were close to hyper-being (itseke) and, in more unusual moments, also to kuge people. And it is fundamentally because of this ambiguity of behaviour that the upper-xinguans need to maintain a “good distance” and, additionally, frequently re-evaluate the possibilities of relationship with these beings who are so feared and, at the same time, so desired.