1. Introduction

The extended promise of affordable housing to the common person, in contrast with the congestion and squalor of Mumbai, became part of Navi Mumbai’s unique appeal. The city of Navi Mumbai (New Bombay) was envisioned as a twin city to Mumbai (Bombay) located on India’s western coast in the state of Maharashtra. Originally planned to offer a plethora of affordable housing schemes, it gradually ascended into a dominant haven for the ‘middle-class’. The idea of this new town on the undeveloped mainland, evolved to foster an eastward ‘metropolitan’ development of Mumbai. The twin-city, planned as a ‘counter-magnet’ on the eastern mainland across the Thane Creek from the ‘island city’ of Greater Mumbai, is sandwiched between the creek and the Sahyadri hills. The concept of the ‘counter-magnet’, replicated from the Garden City Movement, intended to decongest the existing city by redirecting the uncontrolled urban growth. Two functional problems to Bombay’s development were stressed in the conceptual master-plan blueprint. (Correa, et.al., 1965). One is the growing population and the incapacity of the congested city to accommodate it. The second is the enforcement of a north-south axiality in traffic patterns, perceived as jeopardising a healthy urban expansion.

Navi Mumbai signifies India’s largest post-independence urban project, encompassing an area of 343.70 sq.km, implemented piecemeal over a timespan of over five decades. Planned as a purported ‘metro-centre’, the city evolved at tangents with its original intent to decentralise Mumbai’s N-S axiality. In the planning of habitation, a predilection for mid to high-rise housing development to facilitate suitable densities was exercised, while the focus of the plan was to devise affordable housing as a new model for peri-urban habitats. The ‘Artist Village’ by Charles Correa and ‘CIDCO housing' by Raj Rewal catering to the lower income groups and based on incrementality, and Government Employee cooperative housing societies are notable affordable housing models of Navi Mumbai. As the implications of the development plan are currently under review, the paper presents a critique on the planning policies and the socio-spatial environment it produces. Dominant issues of urbanisation (such as the formation of slums) that have plagued Greater Mumbai now extend to Navi Mumbai.

Though the market for ex novo cities has saturated in some western countries, greenfield cities are still being actively planned and built across the globe from Masdar (UAE) and Songdo (South Korea) to Dholera (India). Primarily planned as intense capitalistic hubs that capture global capital and labour flows, it is imperative to dwell on the human and social dimension these planned habitats produce.

2. Theoretical and Research Framework

The paper examines the spatial logics of habitation in Navi Mumbai, arguing that built-in spatial inequities and changing economic conditions across the millennial turn have led to a disconnect between vision and intentions of the master plan and the emerging realities.

The research questions the initial ambitions and intentions in the planning of habitation in the advent of its current realities. The central motive of the research question attempts to address the emergence of slums in a planned city, one that was designed for majority residential buildings with affordable schemes. The existing city’s theoretical understanding is limited to the vision and concepts offered by its architects/planners. In order to examine points of fissures in the vision and implementation, the research attempts to retrace conceptual/influences, by dissecting not only the vision and concepts published by the urban designers, but also possible alternative global concepts that might have influenced the Indian context during the same time period. Using the help of case-studies as simulative examples of planning morphologies and their trajectories, Navi Mumbai’s contextualisation and spatial logic of housing (design, planning and policies) are read five decades since inception, in order to lend to new perceptions of the planned city.

The first section of the paper examines the spatial logics in the configuration of habitation in Navi Mumbai. The initial vision of concepts of Fordism and industrialisation, import of ‘Euro-American’ ideas, incrementalism and suburbanism are theoretical lenses through which Navi Mumbai’s spatiality is explored, by revisiting the preliminary conceptual settings of its spatial geographies.

In the second section (subheading 5 onwards), the points of fissure (or disconnections) in the state of habitation in both the planned areas and emerging unplanned areas. The research uses qualitative research methods, relying on textual evidence, building policy and development plan documents, and archival material. Annapurna Shaw’s The Making of Navi Mumbai (2004) was a critical resource, offering an in-depth understanding of the early three decades of Navi Mumbai’s inception.

3. Inception of Navi Mumbai

In the 1960s, urban planning strategies aimed towards controlling urban growth. Mumbai’s fast-paced debut as a metropolis, through the growth of its municipal delineations significantly updated in 1950, 1957 and 1965 necessitated new imaginations of ‘regionalised’ and ‘metropolitan’ growth. Within the purview of the Maharashtra Regional and Town Planning act, 19661, Navi Mumbai was first incorporated as a ‘Metro Centre’ into the Bombay (Mumbai) Metropolitan Region delineation in 1967.

As a conceptual idea, prominent architect Charles Correa, urban planner Pravina Mehta and structural engineer Shirish Patel proposed a Master Plan of ‘New Bombay’ (Navi Mumbai) in the 1965 publication of the art and architecture journal, MARG (Modern Architects Research Group) (Correa, et al., 1965). The blueprint gained a cult status, capturing the imagination of the well-read and elite classes. The public interest garnered, and the dialogue with government authorities over the next five years set these plans in motion.

In 1971, the Maharashtra state formed the public sector undertaking CIDCO (City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra), as an exclusive development body for the planning and development of Navi Mumbai. The New Bombay: Draft Development Plan (DP) was proposed by CIDCO in 1973 and sanctioned in 1979-80. This development plan became a statutory document with enforcement controls over land for a 20-year timespan. Within the 343.70 sq.km delineation, carved out of 95 revenue villages across Thane and Raigad districts, a major chunk was undeveloped agricultural land (166 sq.km). Pre-existing developed parcels of gaothans2 (50 sq.km), saltpan land (27 sq.km), and government owned land (101 sq.km) under MIDC, MSEB, and the Defense Department existed within the delineation. The public and private lands were developed in phases across 14 planned nodes after land acquisition by CIDCO. Of the total population of 20 lakhs (as per 2011 census), the planned nodes (similar in size and scale to self-sufficient townships) with 3.7 lakh dwelling units house a population of 11.8 lakhs (CIDCO, 2011), with the rest of the (mainly preexisting) population residing in gaothans. CIDCO’s scope of work was restricted to the planned nodes and infrastructure connecting them, approached as a greenfield development. In order to self-finance the development under a revolving-fund mechanism, land was used as a resource. In 1992, the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC) was formed and CIDCO ceded the control of its developed nodes to it.

In a retrospective article, Charles Correa remarks on the state’s persisting obsession with Bombay, “A city in a very advanced stage of pathological decay, going through the spastic death-throes which superficial observation mistakes for ‘energy’” (Correa, 1997). Under the conceptualisation and delineation of the CBD (Central Bussiness District) nodes, the city was planned as a centre with tertiary employment, under the ‘tacit agreement’ of relocation of government offices from the Mumbai’s old colonial CBD (Fort area), which did not materialise. Commercial enterprises and Industries of MIDC first envisioned as supportive economies became central to Navi Mumbai’s economy until the early 90s when industrial development declined. The notion of Mumbai’s CBD in the southern tip and its island geography as restrictive dominated, against the normative image of the metropolis, with a central core and concentric accretions of urban growth. Within contemporary scholarship, the normativity of this concentric ‘metropolitan’ image is critiqued, but Bombay’s centrality despite its geographically induced congestions is also noted. (Figure 1). Its dependency on Greater Mumbai and perception as an extension of Mumbai, conflicts with its original aspiration to become an independent self-sufficient city with a robust economy and employment pool.

While outlining the vision for the city, Correa, Mehta and Patel (1965) wrote:

“This area would then develop into a new self-sufficient city whose continual contact and exchange with the older city would be primarily for social, cultural and commercial reasons and not as a ‘dormitory’ area feeding the already overcrowded island”.

CIDCO, https://cidco.maharashtra.gov.in/

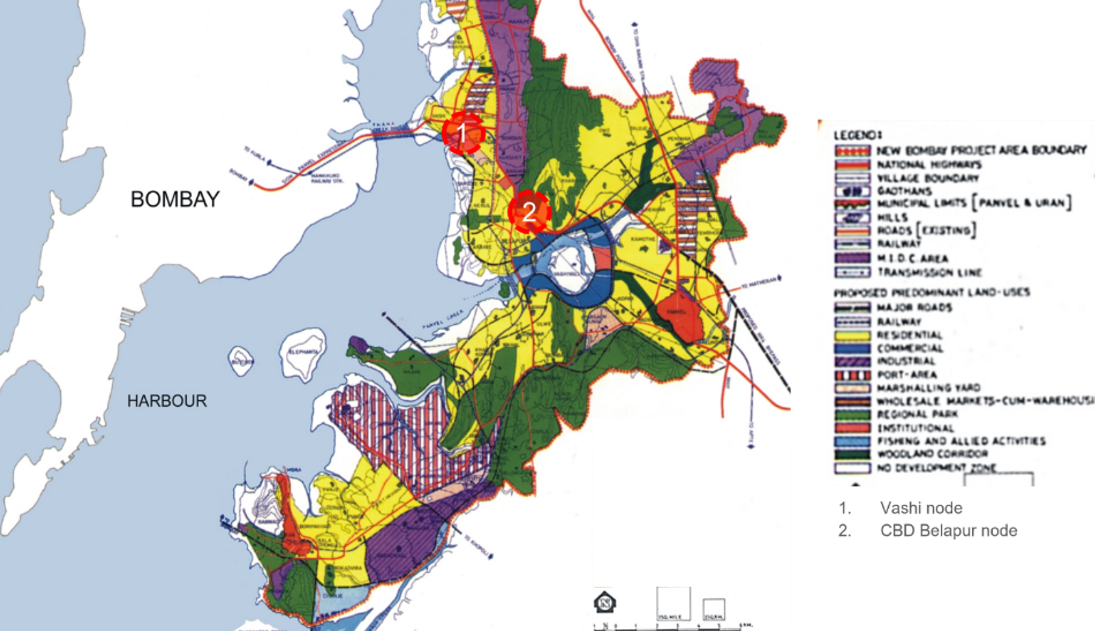

Source Figure 1 Development Plan and Structural Plan for Navi Mumbai indicating residential land (yellow) allocated adjacent to MIDC industrial corridors (purple)

Unlike satellite city development, Navi Mumbai (343.7 sq.km) was envisioned as a large ‘metro centre’, roughly the size of Greater Mumbai (437.71 sq.km) to house a 20 lakh (2 million) population. In comparison, the planned city of Chandigarh (including the peripheries) of 114 sq.km intended to house half a million population. This model mimicked the ‘largeness’ of international planned cities (Edulbehram, 1996) such as Washington D.C and Brasília. With the overshadowing of the micro and meso, the pursuit rested on the grandiose scale in the city planning.

4. Planning Influences, Concepts and Contextualisation

Shaping of Planned Habitation

The visual landscape of Navi Mumbai emulates an austere environment (characteristic of the modernist principles), predominantly populated by ‘government’ style mid-rise apartment typologies, crude simulacra of modernist ‘functional highrises’. In the proposed CBD node of Belapur (Figure 1), and the oldest and highly developed node of Vashi, land-use zoning provides for high rise apartments. 50 years into its existence, as its first housing stock ages out, the assemblage carries visible signs of blight. The housing stock is composed of CIDCO-built housing (37%) and those developed by the private sector (63%). The allocation of housing categorised by income group is as follows: LIG/EWS (upto 25 sq. m.) 16.5%, MIG-I (25- 50 sq. m.) 48.6%, MIG-II (50- 75 sq. m.) 22.1% and HIG (above 75 sq m.) 12.8% (as of 2011) (CIDCO, 2011). Shaw attributes the quality of CIDCO-built housing as the ‘lowest minimum possible’, equivalent to chawls in Greater Mumbai (industrial housing typology built for the working-class) (Shaw, 2004, pp.174). The CIDCO-built housing stock included tenements for HIG, MIG, LIG, as well as EWS3. Vacant ‘serviced plots’4 allocated for various residential land-use typologies of co-operative housing, bungalows, row houses, bulk residential plots and GES plots5 could also be purchased and built-on privately. Land-use categories of different housing groups - the bungalow and row house accessible to high income groups, and the ‘sites and services’ (small vacant plots) availed by the poorest sections, created spatial segregations (Shaw, 2004, p.13, p.18). Key stakeholders for housing types were majorly new citizens (employed in tertiary sectors), the migrant construction and industry workers (in the new petrochemical, quarry sites, and technology parks) and the native residents resettled in gaothans.

Spatial Logics of Habitation

The second Iran International Congress of Architects (IICA), held in Persepolis-Shiraz in 1974, and the first UN Habitat conference (Vancouver, Canada in 1976) were crucial in setting the stage for global exchange of ideas on human habitation, especially in developing countries. The novelty of this international discourse was evident in the architectural outcomes of prominent Indian architect’s participation in the congregation, who were later part of the design of government housing schemes in Navi Mumbai. As a master architect and urban planner, Charles Correa’s adherence to his seven principles (‘Incrementality, Pluralism, Participation, Income Generation, Equity, Open-to-Sky Space and Disaggregation’), as advocated in his seminal work ‘The New Landscape’ is extended in buildings such as Tube Housing and the experimental PREVI Housing, along with architects Raj Rewal and Uttam Jain adopting newly conceptualised philosophies of critical regionalism. (Sedighi and Varma 2018). The 1970s global urban planning theories give us an interesting glimpse of revolutionary changes that took place in the urban context in post-Independent, post-colonial India. In the urban scale, creation of new housing rested on a 'Fordist' notion of planning that made new land available on and adjoining industrial land, and when mass-housing was governmentalised in order to create the ‘ideal suburbia’ for the ‘working-class’.

Using this premise, Navi Mumbai’s conceptual planning can be positioned as influenced by global practices. The following section examines the following five key urban planning concepts and influences that determined Navi Mumbai’s habitat configurations, applying a theoretical lens to examine the spatial logics of habitat planning.

Euro-American visions

Suburbanisation

Fordism

Industrial adjacency

Incrementalism

4.1 Euro-American Visions

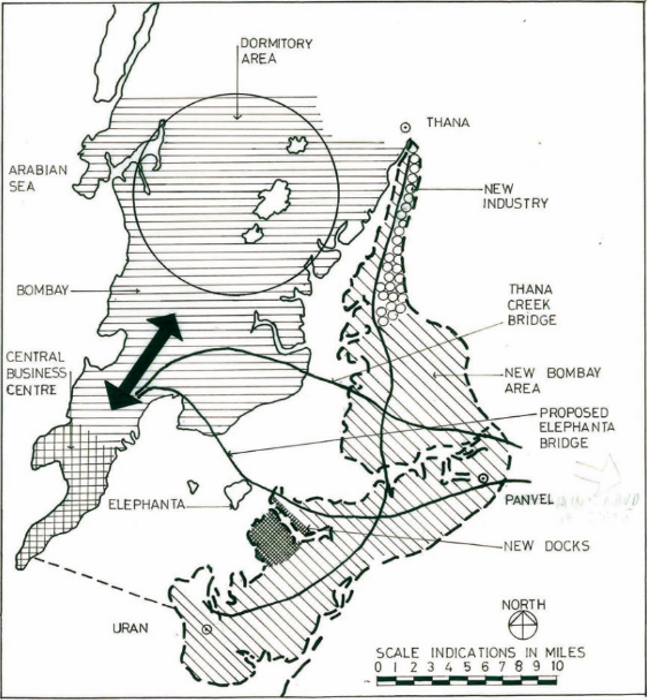

The 1960-70 epoch in Indian urban planning viewed the existing post-independence cities as ‘saturated’ and extended an intentional focus on ‘the larger problem’ towards building new, independent cities, reliant on the metro. In ‘Planning for Bombay’, (Correa et.al, 1965) discuss the planning conceptualisations for defining the idea of the ‘satellite city’. In this case, ‘satellite was imagined as a system of planets, interlinked with a network of resource reliance, such as the gravitational pull between mass and proximity. Here, the distance of small (satellite) towns away from the main metropolis centre was seen as a negative force to urbanisation with a physical disconnect to the main city. Therefore, the satellite town vision was greatly reliant to the services already present in the mainland, so as to subsidise costs (Correa et al., 1965). The planning intended to break the N-S axiality of Mumbai’s linearity and redirect growth. (Figure 2).

In the 1960 and 70s, the points of reference for city planning of Indian post-independence modernist cities included the British colonial towns, and the ‘new towns’ channelised by the Garden city movement6. Chandigarh, one of India’s first generation planned cities, also served as an ideal model of the greenfield city in the Indian context. Its landmark development blazed the trail for Navi Mumbai. The culture of building ‘green-field’ cities through mass conversion of agricultural land set-forth in the making of Chandigarh deeply influences the making of cities to this day. This mainstreamed the capture of hinterlands by the rich (industrialists) and the urban elite class with dislocation of the native locals as accepted practice for future city developments.

https://www.designcurial.com/news/charles-correa-1930-2015-4603293/3

Source Figure 2 Conceptual Planning of the New city (1964) - indicating proposed connections between the main metro city and proposed satellite city

The conceptualisation also relied on ‘seemingly utopian’7 urban strategies, from the modernist zeitgeist such as ‘land-use’ and ‘transit planning’ and the Garden City Movement. There is weight to Fitting (2002)’s critique of Chandigarh’s utopian planning, wherein “the imposition of one "man's" Utopian vision on a culture results in destructive imperialism.” Chandigarh, a direct translation of western ideas of planning, imposed grid-iron layouts, sector planning, hierarchies and typologies. These strategies were critiqued for decontextualising and glossing over the complexities within the Indian milieu.

“Chandigarh […] lacks a culture. It lacks the excitement of Indian streets. It lacks bustling, colourful bazaars. It lacks the noise and din of Lahore. It lacks the intimacy of Delhi. It is a stay-at-home city. It is not Indian. It is the anti-city.” (Kalia (1994), cited in Fitting (2002)).

4.2 Fordist Planning theory and influences on Navi Mumbai

Fordist urban planning theory gained popularity in the USA and western Europe between 1930-1970s with the on-going economic structuring. Fordism was an economic model of mass production and mass consumption (Jeckel, 2021). The key intentions of the post-war USA were separating residential areas and workplaces as distinct areas, as part of distinguishing the unique identities of the urban core and peripheries. (Roost and Jeckel, 2021). Key aspects of Fordist spatial planning include locating industrial districts in the outskirts of the cities, mass production and consumption linked economy and the emergence of the new suburbs. Post-war (Europe and USA), urban planning was highly influenced by Marxist urban theory where the built environment was a site of production. The planners lacked a “map of social reality” (Roweis, 1981). This period of urban spatial organisation was led by State’s interventions and large-scale corporations. The industrial landscape largely guided the shaping of the cities.

The vision of the State Government and planners also followed the Fordist approach of formation of homogenous districts of residential and industrial, promoting segregation and separation. Here, the paper questions the impact of Fordist segregations on housing, specifically in terms of policy accessibility and exclusions, as discussed further in section 5.

4.3 Suburbanisation

In the post-war USA, restructuring housing through the ‘New Deal Housing system’ by way of creating ‘the new ideal suburb’ at a safe distance from the city, was seen as a way to boost the domestic economy (Florida and Feldman, 1988). During this time, suburbanization offered the ‘solution’ of expanding its infrastructure of mass economic production. Suburbanization was led by government programs and led to highly segmented social class relations. The focus of the Fordist city was generating the cycle of production-wage-consumption (Florida and Feldman, 1988), linking suburbanisation to industrialisation. Residential land accounted for a majority (46.64%) of land-use in the Navi Mumbai planned areas (Shaw, 2004). As opposed to an independent city, the spatial organisation of Navi Mumbai emulated a sprawling suburban extension to Greater Mumbai, with low-income housing as urban centres reliant on rail transit to and fro the metropolitan economic centre. While the Fordist planning led to racial segregation via zoning in the USA, affordable housing in Navi Mumbai created a patchwork of infrastructural exclusions. The focus of housing to be the primary anchors and identifiers of the city, preceded several linkages- spatial, infrastructural, social, intangible.

4.4 Industrialisation and the Perils of industrial adjacency to Housing

As India underwent rapid industrialisation, industrial townships with a unique urban spatial form emerged post-independence influenced by the Fordist model. The ‘industrial township’ was a dominant typology among the 112 ‘new towns’ being built in India at the time of Navi Mumbai’s inception (e.g., Jamshedpur, Bhilai). It accommodated India’s rapid industrialisation as the supporting economy.

The post-war order simulated the need for cities to represent ‘production-wage-consumption’ (Florida and Feldman, 1988). The Planning of the MIDC area preceded the development of Navi Mumbai (Shaw, 2004). (Figure 1). Established under the MIDC Act 1961, the role of the MIDC was to ‘develop’ land to support industrial infrastructure. The location of the MIDC lands was planned as the outskirts of the main city and in proximity to the new Satellite towns. The MIDC Thane-Belapur belt was wedged along the base of the Parsik hills on its west.

Here, the idea of the industrial adjacency is examined and assessed to evaluate its role and impact on housing, inclusion of indigenous farming communities and migrant housing. The intentions of MIDC zones were independent and isolated, and the vision of the new satellite city models was designed as a model dependent on the core metropolitan city. The gaps in planning vision are apparent in the unplanned areas left vacant by the planning authorities. Moreover, ‘The MIDC act’ overrides the ecological disturbances caused in the course of its planning conceptualisation. The industrial zone’s physical proximity to the planned nodes and the ecologically sensitive terrain has allowed for the exploitation of hills as quarry sites from the industrial district.

4.5 Incrementality and the manufacturing of housing prototypes (housing scale)

The fourth conceptual vision of the new city that the paper examines is incrementality with respect to housing, which was seen as an instrument to guide the inclusion and acknowledge the upward mobility of low-income groups in urban areas.

Examining housing typologies

Navi Mumbai’s vision was rooted in a new urban landscape of low-income housing schemes (Shaw, 2004), that were based on low-rise, low/medium density prototype units. Broadly, the housing typologies in Navi Mumbai include: CIDCO housing (tenements and non-tenements), cooperative housing societies, bungalow or the row houses, and private housing (Shaw, 2004) made available for broadly four income groups - EWS, LIG, MIG and HIG. At the inception of the city planning, the civic authorities awarded eminent architects contracts to design model housing: Uttam Jain (Panvel, 7), Charles Correa (Artist’s Village), Kamu Iyer, Hema Sankalia (Hudco & CIDCO Housing Sanpada New Bombay) and Raj Rewal (CIDCO Housing) (Ugrani, 2020). The architects consciously emulated an ‘alternative modernism’8 shaping the notion of ‘regionalism’ in India (Sedighi and Varma 2018). ‘Critical Regionalism’ - a term first coined by Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre in the late 1970s as a reaction to the placelessness of the International Style dominant at that time. The discussions of ‘critical regionalism’ were focused on visual contextualisation, incorporation of architectural elements of regional continuity, however, did not specifically address issues of urban scale.

Incremental Housing and the inception of affordability

Architect-designed pilot projects such as ‘Artist’s village’ of ‘incremental housing’ were launched under various housing schemes. Charles Correa’s ‘artists village’ was a visionary model of an ‘urban-rural’ typology. The housing cluster was built to attract the artists from Mumbai to Navi Mumbai in order to generate new cultural environments in the greenfield site. A unit prototype was envisaged for the low to middle income groups, that would cluster as a mass housing model for the newly urbanised city. The housing scheme was subsidised to attract artists from Mumbai to Navi Mumbai. The housing toolkit was a set of 4 typologies, starting with the smallest unit. Design options and suggestions were demonstrated for the houses to expand. In an attempt to allow for the transitional housing to emulate the rural/pastoral landscape of the urban peripheries, Correa chose to adopt a module of housing that was rooted in social cohesion and of individual units, yet with the vision of urban living with private and shared courtyards. The picture presents an ‘idyllic’ living of the ‘Indian’ suburb, with spatial constraints and density. The second housing examples is the CIDCO low-income housing designed by architect Raj Rewal, that embraced the Indian vernacular aesthetic, incorporating the rural lifestyle in the living spaces. The unit types vary in size from around 20 m2 to 100 m2 integrating terraces, balconies, in-built storages.

The third example is the Uttam Jain Housing, in sector 7, Panvel that was part of the CIDCO Housing Scheme, designed as a cluster of 285 units in a twin housing typology.

The toolkit of incremental housing in architectural discourse was not only vital to establish the new image of the urban vision, reimagine a transitory identity of the new city, but also to formalise the idea of ‘self-help’ change and growth by a family unit. The architectural commonality across the housing schemes was that the units offered the possibilities of augmented semi-open spaces as an extension of the indoor areas for opportunity to extensions and appropriation. In India, it is common for a family unit to function as a ‘joint-family’ system, with the multiple generations living together. Charles Correas’ artist village was unique in a way that he formally acknowledged the habitat patterns of pastoral landscapes. The unit sizes of phase one include a singular room, with the washroom utility outside as an independent unit, and the kitchen as a possible extension- representing the socio-cultural spatial structure of an Indian dwelling unit.

Incremental urbanism serves to address the urban issues of the present, focusing on the assimilation and adaptation of the residents within the built and economic landscape (Baitsch, 2018). The framework for incremental housing extensions thereby accounting for the expansions of the family unit. A ‘sites and services’ approach with provisions of serviced land to build incrementally was extended to the poorest population. The study situates the ‘sites and services’ exercises carried out across the globe as prone to failure, further demonstrating the success of the models in Navi Mumbai due to its well-serviced placement, in a planned neighbourhood (Owens et.al, 2018). For an understanding of scale, the Airoli node had around 18190 such plots planned in 1985 spread over a land area of 1.55 sq.km.

While visual surveys suggest the quality of this ‘self-built’ incremental housing to be no different from slums, some empirical studies have noted the ‘sites and services’ within Navi Mumbai as a successful exercise in incrementality (Owens, et.al, 2018).

In part 1, the key hypothesis/questions the paper assimilates are:

Although incremental housing was a model for affordable housing, the masterplan could not include, assimilate or seamlessly integrate the housing projects with existing villagers, migrant workers. Its specific instructions made it difficult to operationalise, and susceptible to failure.

If incremental housing was a stepping stone project for rural-urban assimilation, envisaged between 1970-1990s, how did the municipal authorities look at future assimilation projects- post-2020s?

The following section introduces part 2 of this article (‘examining fissure’), discussing the after-effects/ consequences of the broad urban concepts, through a spatial analysis of the urban spatial form across the millennial turn. It aims to offer a theoretical lens to the understanding of the urban growth trajectory, five decades since its inception. It also offers a critique to the possible points of fissures in housing strategies.

5. Fuzzy Spatialities: Emergence of Unplanned Habitation

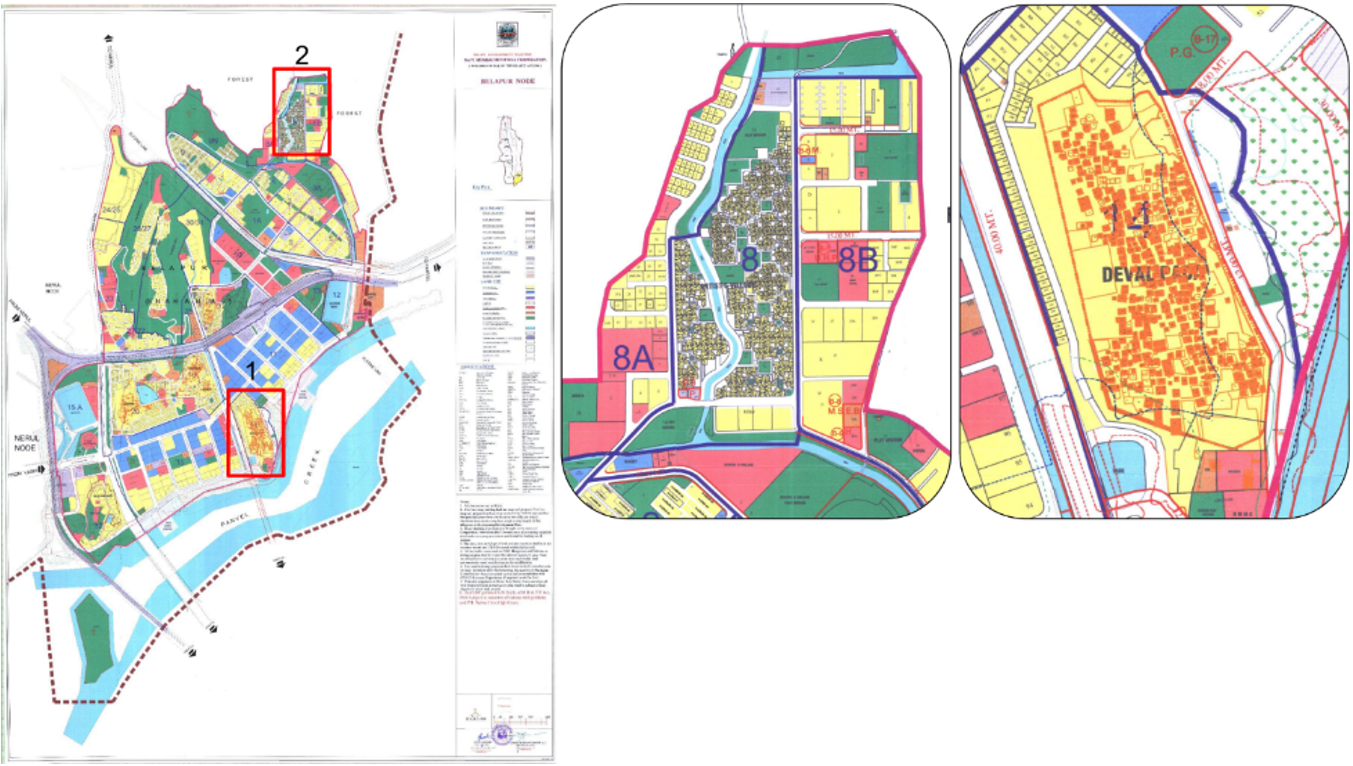

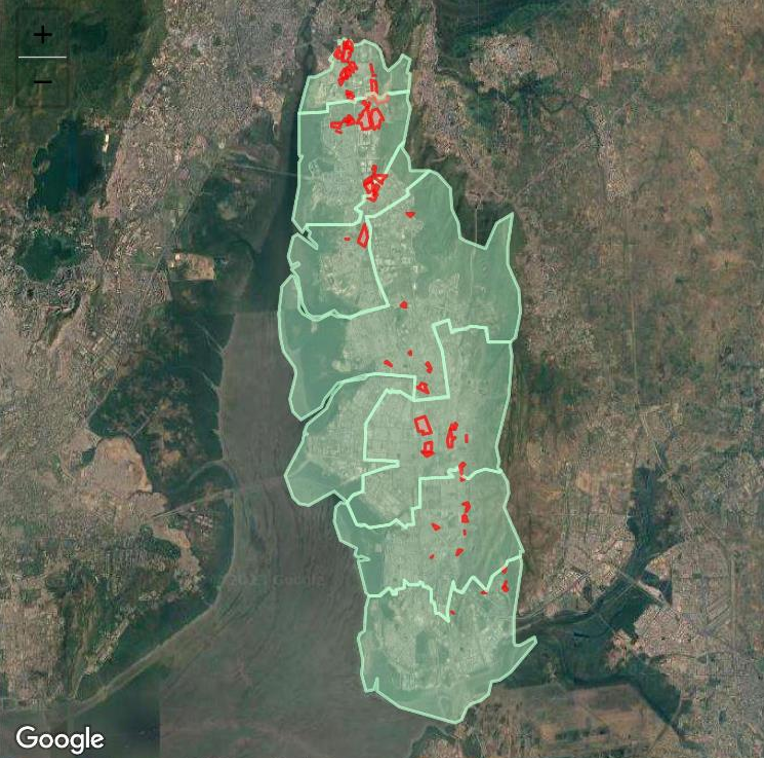

In this section, we analyse indigenous and subaltern urban morphologies such as ‘slums’ and ‘gaothans’, their positioning within the planned city, and the politics of the respective community’s engagement with urban implementation policies causing segregation (Figure 3).

Google Earth, Overlay illustrated by author

Note Source Figure 3 Fuzzy Areas: A cross-section of land adjacencies

5.1 Gaothans

The native pre-existing population, and their descendents, previously subsisting as farmers, fisherfolk and salt-pan workers, now primarily reside in ‘gaothans’9 (urban villages). In Navi Mumbai, special ‘gaothan’ planning areas were allocated to house the resettlers of eviction. Under the Gaothan Expansion Scheme (GES) and the Twelve and a Half Scheme, CIDCO released some proportion of land and affordable housing respectively to the project affected native population. Imbalances and corruption existed within this distribution (Shaw, 2004).

This GES scheme allocation process was far from equitable, with larger land owners bearing greater benefits from the remuneration and land allotments. A large section of the displaced became dispossessed, settling in squatter and slum settlements given the inequities in land acquisition processes (Shaw, 2004, p.221). In the face of active resistance, CIDCO formulated various inclusive measures and policy incentives to the farmers including vocational training to situate themselves in urban-industrial occupations, educational and career opportunities to family members. Some of these were in fact counter-measures to mitigate the slow-down in the land-acquisition process, the increasing resistance and protests, and to erase the ill-effects of the previous forced land eviction undertaken by MIDC a decade earlier.

Within the industry-based city development of Navi Mumbai, urban industrial occupations were forced on the displaced farmers, enabling free flows of working-class labour. Shaw also notes that the hill edges were home to many Adivasi (indigenous people)/ tribal groups, residing in ‘adivasi pada’/tribal hamlets who remained undocumented in the master planning process, and further unable to access benefits availed by other original inhabitants resettled in gaothans (Shaw, 2004, p.236). Whether caste and class divisions influenced the mobilisation of planning strategies and prompted these spatial exclusions remains largely understudied. Caste-based spatial inequities are mostly region-specific and not well understood within Navi Mumbai’s social fabric.

The State’s dialectic control of land-use is seen when the premise of land-conversion is for the welfare of the people, but also to enact Government’s independent agenda (as in the land developed for corporatisation). Here, there is a “redefinition of territoriality is a conflictual and contested process”. When CIDCO assumed an authoritarian approach in the land acquisition process, it faced resistance and sometimes violent protests from locals and political fronts with over 3000 families displaced. The act of retaining urban villages (Figure 4) as a means of low-income urban labour from agricultural occupations, is an act of ‘pauperisation’10 by the State, where the urban policies continue to produce urban poverty in the process of newly planned urbanisation (Edulbehram, 1996).

5.2 The Development of Slums

In Navi Mumbai’s context, Shaw highlights the ‘dualistic outcomes’ of master plans within planned cities, wherein ‘unplanned’ slums and shanty towns emerge in parallel to ‘planned portions’ of ordered space (Shaw, 2004, p.1). In the 1960-70s, the deeply embedded Euro-American conscience in Indian urban planning festered perceptions of emerging informal settlements as unsightly areas to be corrected through planning recourse and enforcement. Slums emerge as resilient creative solutions by the cash-strapped urban poor in the absence of affordable housing solutions. Slums cluster on government or public land, in voids and inconsequential spaces such as the verges of railway tracks, along transit lines (highways and expressways) and beneath flyovers and low-lying swampy areas (Prasad, 2003). The history of slums in Navi Mumbai matches the timeline of its planned settlements. In a 1991 census survey, around 29 slums were identified, with an estimated population of around 50,000. (Shaw, 2004). CIDCO perceived slums as ‘unauthorised’, demolishing outcrops from time-to-time. These settlements do not have access to civic amenities of permanent shelter, electricity, water supply, sanitation, garbage removal, street lights, paved streets and social infrastructure such as schools and clinics, which are accessible to gaothans. Despite India’s euphoria of a newly independent nation (1947), inherited colonial mentality perceived slums and squatter settlement as an enforcement problem to be tackled by eviction and displacement. Since a bulk of land and real-estate development occurred under purview of the State (CIDCO), the state’s mechanisms for eviction and rehabilitation operated differently from Mumbai. Slums hold a more precarious position in Navi Mumbai than in Mumbai given that a bulk of the housing stock was built with affordability in mind. A specialised statutory body (like SRA of Mumbai) for rehabilitating slum dwellers is absent.

CIDCO, https://cidco.maharashtra.gov.in

Source Figure 4 Urban Villages and their spatial boundaries outside of the planned areas within Belapur Node

A progressively nuanced analysis of informal morphologies and their inter-relationship with the formal emerged in 21st century scholarship. In cities in the Global South, informal settlements present a “generali(s)ed mode of metropolitan urbani(s)ation” (Roy, 2005) as a binary to formal systems. “They are so economically, spatially and socially integrated with their urban contexts that most developing cities are unsustainable without them, yet the desire to remove them persists and is linked to issues of urban imagery and place identity” (Dovey and King, 2011). A majority of the economic activities in Indian cities lie within the informal sector. Despite this, no land allocations are found within the Development Plan. Since the informal is not allocated within land use planning, it often manifests as a non-plan activity within designated public space areas and vacant parcels of government land. While stats greatly vary, over a billion individuals in metropolises in the Global South reside in informal settlements (Dovey et al., 2020). As a metropolis with considerable migrant flows, Mumbai presents a robust informal sector economy that provides a supportive ecology to its formal systems (Chopra, 2018). The undefined place of the informal sector in terms of economy and housing within the planning of Navi Mumbai deterred the sustainable economy and habitation within the city (Shaw, 2004). The extensive public (acquired) land, lying vacant as the ex-novo city was gradually taken over by slums (Figure 5).

“Informal morphogenesis is strongly geared to both natural topography and existing infrastructure.” (Dovey, et.al, 2020).

Spatial Slum Information, Shelter Associates, https://app.shelter-associates.org/

Source: Figure 5 Slums pockets identified and mapped in Navi Mumbai, seen predominantly within/near the MIDC belt

Within Navi Mumbai, certain typologies of slums attach themselves to pre-existing gaothans (marked as special preserved zones within the masterplan). The placement enables access to water, sanitation and other urban resources allocated to the gaothan through the GES scheme. Informal settlements' anchorage along transit corridors, for example along Navi Mumbai’s suburban rail network and the Thane-Belapur Road, are a direct necessity for ease of mobility and access to labour markets. The Thane-Belapur transit corridor, the major arterial spine running north-south through Navi Mumbai presents a unique case of planned development on one side in juxtaposition with slums. A visual survey on Google earth suggests a dominant accretion of slums on the western side of the arterial road in the 16 km long MIDC industrial belt zone. MIDC zones are public land (or land sold/leased to industrialists), under the administrative control of the MIDC. Perhaps the various industries and developers had a lenient approach to workers under their employment. The MIDC land acquisition process of the 60s, pre-dating Navi Mumbai’s, was notorious for its forced evictions of farmers and unequitable remunerations (Shaw, 1990). The sole livelihood of the dispossessed was the land (Shaw, 2004, p.196) and it is possible that the evicted settled down as squatters within the MIDC land right after. For a large-scale urban project built piecemeal over five decades, considerable oversight is seen in housing the labour forces needed to build it. In the absence of dedicated housing for construction industry workers and labourers, pockets of slums emerged as a solution to their housing problem. Also, studies and frameworks for understanding slums, the informal processes and economies within Navi Mumbai are largely absent.

“(...) the expansion of urbanism into peripheral rural areas expands the economic opportunities available to the already 'impoverished' locals. But the process is actually one of proletarianization and pauperization, in which the labor is freed up for working on the developmental activities (construction, etc.) in the area itself, for industry in general, and for domestic help. They join the ranks of the 'urban poor' who are then blamed for blighting the city with 'slums'.” (Edulbehram, 1996).

The disparity in infrastructure and resource allocations of the planned node within the gaothan is just as apparent, as within the ‘slum’. Edulbehram (1996) links the idea of the land conversions to ‘proletarianisation and pauperization’, questioning the power of the State- dialectics of land-conversions. He talks about the paradox of land-conversions as an instrument to serve the housing needs of the urban poor, but at the same time, as a means to exercise power over land allocations for State interests. This dialectic is also seen in the ‘disassociation’ of planning interventions within the ‘goathan’ (village boundaries), to formally establish linkages with the ‘planned urban’ areas.

6. The State of Planned Housing

The premise of Navi Mumbai was the promise of “serviced affordable land that allowed low-income and rich families to build incrementally.” (Mehrotra and Sharma, 2018). Primarily, two beneficiaries are indicated as future residents of Navi Mumbai. With the counter-magnet mechanism, two types of inward migration were expected. A mass exodus of Greater Mumbai to this new ‘metro centre’ was anticipated. The centering of Navi Mumbai’s development around the pre-existing MIDC belt also intended to capture rural to urban ‘migrant inflows’ otherwise aiming for Mumbai. The catering of Navi Mumbai to the middle-class was an unplanned (Shaw, 2004, p. 111), but dominating trend.

6.1 Economic Liberalisation and Affordable Housing

The timeline of economic liberalisation is relevant in the discourse of affordability of housing in Navi Mumbai. Pre-liberalisation, India’s urban space was increasingly controlled by socialist policies (Rajagopalan, n.d.). In this era, The EWS/LIG housing within CIDCO-built housing stock accounted for 50-80% of each planned node (Shaw, 2004, p.184). It is safe to assume that the percentage of EWS/LIG in the total housing stock built would have declined further from the 16% it was in 2011 (CIDCO, 2011).

Charged by capitalistic and neoliberal undercurrents of India’s economic liberalisation in 1991, the existent development of Navi Mumbai shifted focus to service the elite and middle class, despite the initial endeavour for socially just housing solutions. By promoting private and foreign investments, industrialisation, and introducing a free-market system, the economic liberalisation catalysed urban growth in states of Gujarat and Maharashtra deemed ‘miracle growth states’ due to their investment ripe climate and presence of industry (Ghuman, 2000). Neoliberal policies suitably explain the accelerated urban growth and investments in Navi Mumbai, which had developed at a slower pace than envisioned in its first twenty years. The 89-90 housing policy change opened Navi Mumbai’s housing to private investment. The increased level of options for housing, cash flows, investment and career opportunities helped in populating Navi Mumbai. The population of Navi Mumbai grew at 119% between 1991 and 2001 (Mehrotra and Sharma 2018).

The process of liberalisation skewed income inequalities in India, with the income of the top 10% population increasing from 34.4% in 1991 to 57.1% by 2014 and the bottom 50% reducing from 20.1% to 13.1% (WID, n.d.). The growing social inequities and income disparities and privatisation of the housing market in parallel with the economic liberalisation played into the unaffordability of supposed “affordable” housing in Navi Mumbai. Some empirical studies attest the market pressures of Mumbai’s capitalistic economy and real estate pressures in Navi Mumbai responsible for the gradual decline in affordability of the housing stock by the urban poor (Jana & Sarkar, 2017). By the 90s, housing for the poorest 30% became unaffordable (Shaw, 2004). Even with the subsidy on the reserve price (the base price set by the CIDCO per sq. ft area), the housing stock became increasingly unaffordable to the urban poor (LIG and EWS).

6.2 Suburban Middle Class and Housing Affordability

Up until 1990, the low-income CIDCO-built housing was made affordable through cross-subsidisation methods from HIG housing (High-Income Group) and commercial developments. From 1989-90 onwards, a change in the CIDCO housing policy allowed private developers to build houses on a turn-key basis. This privatisation of the housing market to increase supply and improve quality escalated the affordability crisis, as consumeristic and market-responsive behaviour favoured higher income groups (Shaw, 2004, pp.174). The range of affordable housing provisions for middle-income groups in Navi Mumbai is more affordable in comparison to other suburban areas at a similar distance from Greater Mumbai, with the added benefit of being a serviced development.

The unaffordability of land due to CIDCO’s escalating ‘developed land’ (service land) prices contributed to the ascendance of the middle-class populace. With the planned nodes, most land-use percentages are attributed for residential land-uses (24.7% on average). (Shaw, 2004, p.146). There is an increased allocation of residential land-use, in place of public institution land-uses (which were ear-marked for a shift in government offices from the city). More than the demand for ‘dormitory housing’ for Greater Mumbai, this addresses a demand for affordable housing in general by the MMR. The deliberate addition of more residential land-use correlates with ‘housing stock’ and ‘land’ sale as profitable sources of revenue for the CIDCO as an enterprise. This extensive residential allocation has led scholars (Mehrotra and Sharma, 2018) to deem Navi Mumbai as a mere ‘bedroom suburb’ of Greater Mumbai. We contest this labelling, arguing that the increased housing land-use alone cannot indicate the transition to a dormitory suburb. We compare Navi Mumbai in juxtaposition to Vasai-Virar11, a suburb located in MMR’s northern fringe beyond Greater Mumbai, often pitted as the competition to Navi Mumbai’s development scenarios and affordable housing. This region witnessed an accelerated growth of unplanned, mass-produced low-end housing, becoming a dormitory suburb, with affordable housing stock, deemed “refuge of the poor” (Jose, 2022). Unlike Vasai-Virar, Navi Mumbai has some degree of commerce and industry that engages the working population locally (68%) (CIDCO, 2011).

6.3 Issues with Incremental Housing

The idea of incremental urbanism was abandoned in the 1990s (World Bank, 1997). With the economic shift, incrementality as a concept rewarding to the low-income communities, already unsupported by policy or praxis, was discarded for profitable ventures. The state of the incremental housing projects not only reached their maximum potential, but most of the home-owners rejected the incremental framework and instead adopted a conventional builder-driven housing layout12. Instead of incremental growth, the home owners completely demolished the existing structure and remodelled a house, independent of the original architectural plan. This meant a complete enclosure of open and semi-open spaces, indicating a disconnect between the phase-wise framework for incrementality, economic upward mobility and architectural aspirations of the homeowners. This also indicates the disconnect between the architect and the methods of the community. The core intentions of incremental housing were to provide a loose and flexible framework that would allow for ‘self-building’, including the opportunity for the residents to express their individual aesthetic styles. However, once the units were completely demolished and built to 100% capacity, the scheme lacked a sense of ingenuity and continuity. The lack of policies to regulate and repair the low-cost housing schemes have left the housing complex in dilapidated conditions. Post-liberalisation, new proposals towards experimenting with the low-cost incremental housing architecture saw an abrupt end and the housing landscape was dominated by builder-driven mass housing. Despite the original intent to be a “... self- help city”, where serviced, affordable land could allow both low income and rich families to build incrementally”, (Mehrotra and Sharma, 2018) the housing stock affordability by low-income groups faced a gradual decline even at subsidised prices and Navi Mumbai became a haven for upper and middle class income groups. Preference of high-rise buildings at par with the high FARs suggested, with the shift in the planning authority naturally excluded low and mid-income populations from accessible and incremental housing. (Mehrotra and Sharma, 2018). The execution of incrementality as a policy, while preferred, there were no mechanisms to do so for high-rise, high density settlements for lower-income individuals.

7. Corporate Knowledge Parks and Changing Housing Needs

The Post-Fordist notion of planning was a reaction to large corporatisation of urban space. Parallel to de-industrialisation processes, the rise of the Information Technology (IT) Industry in India began to reflect in its spatial planning schemes. IT parks mushroomed in metropolitan cities like Mumbai and Bangalore at an unprecedented scale. The Bandra-Kurla Complex13 model for the new Business Park (as a need to reposition a new CBD for the city) aimed to represent the ‘new’ global city, housing the multinational banks, corporates and consulate buildings. However, the business district relies on residents of informal housing outside of its planning schemes to procure domestic and low income labour. The Knowledge, Technology and Business Parks models SEZs (Special Economic Zones) in India are controversially infamous for being hyper-classist models of exclusions, that are incognizant of social spillovers and economic connections (Saleman et al., 2015).

Corporate Business Parks in MIDC, Navi Mumbai concentrate around Ghansoli/Airoli nodes. A singular transit roadway (Thane-Belapur Road) separates the Reliance Corporate Park from the Ghansoli village and the Nosil Naka Samrat Nagar Golden Colony14 slum pocket. The highly privatised business parks, (located on 18 hectares of MIDC land, while of the other 95 plots, 65% are engineering units and 25% chemical units) indicates a total concentration of land towards industrial/commercial use (Shaw, 1990). Consequently, the responsibility of accommodation, utilities and services for the corporate and industrial workers fell on the neighbourhoods adjoining the MIDC areas. The workers in the MIDC zones relied on housing outside the Industrial zone. Much of the housing needs are borne by the CIDCO mass housing schemes, villages and inevitably, through formation of slums. A recent phenomenon that needs to be understood is the demand for a new HIG housing, as the belt shifted from ‘industry’ to ‘IT’ across the millennial turn. Airoli, notably, was one the nodes built with higher concentrations of LIG and EWS for housing a ‘working class’ due to its proximity to the MIDC industrial belt. Gentrification and urban transformation to accommodate the emerging elite class within the node seem inevitable as the site of adjacent work shifts from ‘blue-collar’ to ‘white-collar’. The focus on infrastructure and concentrations of homogenous income groups are aspects that negate affordable housing needs.

8. Policy conflicts and Excluded groups

8.1 Cartographic Omissions

Planning models and the ‘professionally elite’ planners notoriously apply a top-down view of poverty and its alleviation. It is safe to assume that the preparatory surveys before the making of Navi Mumbai often presented the native population as numbers, without co-relationing their geographical locations on existing maps and cartographic documents. These cartographic omissions have persisted for decades, and the making of Navi Mumbai continued to be envisioned as a ‘green-field’ development. Government organisations rely on cartographic maps and surveys inherited from the British colonists, thereby carrying forward the spatial exclusions. Standardised ‘land-use’ categorisations of residential, commercial, industrial, etc. also exclude traditional subaltern morphologies. The revised DP 2018 identifies 21 gaothans (dense villages of residential settlement) primarily belonging to Agari and Koli communities within the NMMC (Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation, 2022). The 2018-38 DP notes that no land documents exist entailing the nature and extents of the koliwadas (indigenous fishing villages) (Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation, 2022).

8.2 Spatial Exclusions

A persisting critique of Navi Mumbai’s planning is the framing of its policies to benefit the rich, while appearing as accessible to the poor (Mehrotra and Sharma, 2018). Land acquisition processes through farmland conversions created systems of exclusion. “The gradual capture of hinterland at the periphery of a city by builders and urban elite by displacing the rural population is in no way different from other processes of ‘development’ visible in the country.” (Edulbehram, 1996). A politically powerful ‘elite class’ was noted to have emerged within the native farmland owners as well, as owners of large parcels of land becoming a ‘wealthy class’ from land compensations. The benefits from CIDCO were often appropriated by the wealthy class, consisting of village leaders, sarpanch and police patil (Shaw, 2004, p.213). The establishment of ‘elitist’ and classist social groups as dominant residential owners escalated discriminatory spatial practices - enforced in the form of exclusive housing cooperatives, gated communities, etc. Socio-economic surveys (CIDCO, 2011) further indicate primarily upper caste (listed as general) (73%) ‘Hindu’ (90%) demographic as urban dwellers. This is critical, in comparison to Greater Mumbai where a heterogeneous cosmopolitan mix of religio-ethnic groups exist. (65.9% Hindu, 20.65% Muslim, 3.27 % Christian, 4.10 % Jain, 0.49 % Sikhism, 4.85% Buddhism, etc.) (Census, 2011). One explanation could be the unbalanced distribution of remuneration based on size of the land. Since upper-caste individuals were likely to have owned larger parcels of land, they reaped better benefits from the remuneration. Given these realities, lower-caste individuals often owning smaller parcels of land could have been pushed further into poverty (finally ending up in slums). As discussed earlier, the aspect of caste in relationship with the allocation of affordable housing in Navi Mumbai remains largely understudied. Another possible explanation is that the tertiary-sector middle-class who decided to migrate from Greater Mumbai were dominantly upper-caste Hindu. Alternatively, Mumbai’s heterogeneous mix may be a result of its cosmopolitan culture and its positioning as a cultural melting-pot.

9. Contextual Delinkages

There is merit to ‘green-field’- cities as laboratories for experimentation in city design, either by imposition of global references (Euro-American Visions, Fordism), or home-grown experiments (incrementalism). The decontextualising nature of the ‘Euro-American’ visions and Fordist and Suburban reference models enforced spatial disparities. The proposed sites for new satellite towns overlooked the complexities of the rural Maharashtrian landscape that were dotted with agricultural and fishing economies, tribal habitats, and local political divisions. The planning vision of the ‘urban’ delinked the notion of the ‘subaltern urban’, or the autonomous potential of small towns/villages to self-sustain and function within their independent identities. With various planning authorities working independently, the housing disparity widened at the fringes. The amassed centrality of the middle-class to affordable housing in Navi Mumbai skewed access of marginalised communities. As the promise of affordability hangs in the balance, considerations for a socially just city are to be prioritised. The paradoxical linkages of economy and affordability become apparent, where capitalism and neoliberalism endanger affordability, but the finance of social infrastructure mandates undisrupted capital inflows. The ‘social’ perceived as disparate from finance and economy should be substituted for alternately financed social enterprise. While the revelled ‘cantonment town’ paints an idyllic picture, colonial planning, by design, enforced segregation and skewed allocation of infrastructure and resources across social classes. Ideas of displacement and dispossession are a byproduct of inherited colonial mentality in planning. Navi Mumbai was not immune to these pitfalls either.

10. Way Forward: Master Plan Futures

The transition from homogenised land-uses, with industrial centralities, to neo-liberal, post-Fordist urban spatialities within the masterplan, requires critical policy interventions and a collaborative approach. From the highly segregated model of planning (habitation), the move towards a liveable mixed-use requires collaborative communication between various actors. The idea of ‘urban development’ needs to shift towards the anti-anthropocene, where the idea of the farmlands and wetlands co-exist with human habitats. A drastic shift towards slum-free cities can be possible by not only adding to the housing stock, but also applying changes in the collaborative policies, and viewing smaller agglomerations as a vital part of autonomous, subaltern urbanism.

The failure to provide a socially-just habitation (though partial and not absolute), and ultimately catering to the middle class and upper echelons of society attests to the planning failure and lack of suitable precedent. The emergence of fuzzy spatialities such as gaothans and slums clearly indicates exclusionary housing practices. It is pertinent to note that the planning of Navi Mumbai happened over five decades ago, and in that regard, critiques comparing the social-justness and inclusiveness of a fifty-year-old planning model would be akin to judging a fifty-year-old movie for its unjust ‘representation’ and lack of ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusivity’. That being said, in the making of a city, a development plan is understood as an iterative process and failures can be course-corrected in the next iterations as best suited to the needs of the future generations. New Delhi, launched the ‘Main bhi Dilli’ (I, too, am Delhi) campaign in 2018 to mainstream subaltern and marginalised voices in its 2041 Master Plan revisions. In the revision of the Navi Mumbai’s masterplan, currently under review, democratic and participatory nature should become the new mandate.