Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicação e Sociedade

versión impresa ISSN 1645-2089versión On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.44 Braga dic. 2023 Epub 23-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.44(2023).4708

Thematic Articles

Transparency as a Quality Dimension: Media Ownership and the Challenges of (In)visibility

1 Departamento de Comunicação, Faculdade de Comunicação, Arquitetura, Artes e Tecnologias da Informação, Universidade Lusófona do Porto, Porto, Portugal

2 Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

O princípio da transparência tem sido considerado como uma resposta política consensual às preocupações com a falta de pluralismo e de confiança no jornalismo. De caráter multidimensional, a transparência relativa à propriedade é uma das exigências legais mais correntes. O foco nos “donos” dos média não é recente, dado o impacto que a propriedade pode ter nos conteúdos produzidos. A propriedade é, por isso, considerada essencial quando se avalia a qualidade no jornalismo. Em Portugal, a propriedade dos média é sujeita a regras de transparência, que implicam a divulgação de informação sobre a estrutura empresarial e dados financeiros, cabendo à Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social monitorar o seu cumprimento. O modo como as empresas de média em Portugal têm respondido às novas exigências legais não tem sido investigado, apesar de essa análise poder contribuir para se compreender os desafios que se levantam ao exercício de um jornalismo independente e plural. O objetivo deste estudo é assim perceber de que modo o princípio da transparência dos média tem sido recebido pelo mercado em Portugal, averiguando os incumprimentos e as objeções levantadas à divulgação da informação requerida. Esta análise, realizada a partir das deliberações da Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social, evidencia o papel central da escala na adequação ao novo enquadramento legal: os incumprimentos declarativos ou pedidos de sigilo partem sobretudo das empresas de menor dimensão, detentoras de média locais ou de revistas especializadas. Ainda, a informação de caráter financeiro é a mais crítica. Estes dados apontam para fragilidades a nível financeiro, o que pode levantar dúvidas relativamente à independência dos média face a agentes externos. Por outro lado, o princípio da visibilidade da transparência não contribuiu para a discussão sobre o cenário mediático em matéria de concentração da propriedade ou de pluralismo, o que demonstra a insuficiência deste princípio como principal política relativa à propriedade dos média.

Palavras-chave: propriedade; regulação; captura; sustentabilidade económico-financeira; qualidade do jornalismo

The principle of transparency is widely accepted as a political response to concerns about the lack of pluralism and trust in journalism. With a multidimensional character, transparency in ownership is one of the most common legal requirements. The focus on media “owners” is not new, given the impact that ownership can have on the content produced. Ownership is therefore considered essential when assessing quality in journalism. In Portugal, media ownership is subject to transparency rules, requiring disclosing information about the corporate structure and financial data overseen by the Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media. There is no investigation into how Portuguese media companies comply with these regulations. However, analysing it could help us understand the challenges facing independent and pluralistic journalism. Thus, this study examines how the principle of media transparency is perceived in the Portuguese market, analysing non-compliance and objections to disclosing the required information. Based on the regulatory decisions, this analysis highlights the central role of scale in adapting to the new legal framework: non-compliance with declarations or requests for secrecy emanates mainly from smaller companies, especially those owning local media or specialised magazines. Financial information is also the most critical. This data points to economic weaknesses, which may raise concerns about the media’s independence from external agents. On the other hand, the principle of visibility and transparency has not significantly impacted discussions on ownership concentration or media pluralism, indicating its insufficiency as the primary policy on media ownership.

Keywords: ownership; regulation; capture; economic and financial sustainability; quality of journalism

1. Introduction

Transparency in media regulation has become unavoidable. Increasingly presented as an essential requirement for the free and democratic operation of societies, promoting transparency is widely accepted as a unanimous approach to addressing concerns about the lack of media pluralism and fostering trust in journalism. As a principle consolidated in ownership regulation through multiple instruments, it goes beyond this single material dimension: it is also a way of combating the erosion of public trust in journalism and news media (Karlsson, 2020).

Transparency, often linked with journalism quality (Lacy & Rosenstiel, 2015), serves as a tool for accountability and enhancing credibility with the public. This is achieved by providing visibility into journalistic production methods (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001) and disclosing the relationships that impact its functioning, crucial given that the media is a cornerstone of the public sphere (Allen, 2008). A well-informed citizenry relies on access to credible and verified information people can trust for decision-making (Strömbäck, 2005). Craft and Heim (2009) emphasise that the public needs “a certain kind and quality of information to aid in self-governance and community sustenance and journalism’s unique qualifications for providing that information” (p. 217). There is substantial evidence supporting the vital role of news media in empowering citizens (Aalberg & Curran, 2012) and their instrumental role in enhancing accountability across various sectors of power (Lindgren et al., 2019; Schudson, 2008).

However, the media could also be subject to instrumentalisation. By often echoing the status quo, they tend to uphold established and powerful players, thereby serving as a tool for legitimising prevailing power structures and social hierarchy (Hall et al., 2017). In addition to the media’s propensity to reproduce the elites’ version, we must also consider the hypothesis of their “capture” by other established powers, such as the government and political agents or property owners (Cage et al., 2017; Dragomir, 2019). Therefore, the exercise and production of high-quality journalism must regularly undergo consistent accountability mechanisms and scrutiny to ensure its effective contribution to democracy, as this function is not a self-fulfilling prophecy (Trappel & Tomaz, 2021).

Ownership and transparency are essential in this context. This perspective has been acknowledged by institutions such as the European Union and the Council of Europe, expressed in various published documents (including deliberations, directives and recommendations). Although it is not the only condition, it stands as an essential requirement if the media are not to be diverted from their fundamental mission. Given their associations with political and economic influence in news production and funding, the media can be held hostage by political and economic interests. Hence, the principle of advocating for transparency is based on the premise that public access to information about media ownership and journalism funding is fundamentally essential.

In Portugal, Law 78/2015 (Lei n.º 78/2015, 2015) mandates transparency in media ownership, management, and financing, overseen by the Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media (ERC). However, the comprehensive implications of the law’s implementation have yet to be systematically scrutinised. What changes and responses has the enactment of this law prompted, both among regulated entities (market players) and the regulatory body? While transparency has not been questioned from a political point of view, it is to be expected that compliance may be contested from the point of view of economic agents. Full disclosure of information can jeopardise companies’ competitive advantage (De Laat, 2018) or conflict with the interests of owners and shareholders (Henriques, 2013). Therefore, on the one hand, it is essential to explore how the principle of media transparency has been received by market players in Portugal, analysing instances of non-compliance and objections raised by owners regarding the required information disclosure. Equally important is examining the regulatory body’s adherence to the new law’s provisions. Drawing from the cases assessed by ERC since the law’s inception until February 2023, this analysis can shed light on the challenges this dimension poses to the practice of journalism in conditions of independence and autonomy, integral to ensuring its quality.

2. Transparency in the Media

Before becoming prevalent in the world of media, the idea of transparency was already consolidated in various sectors, from finance to monetary policies, and had particular significance in anti-corruption strategies as a means to enhance oversight of governmental processes and public money (Craft & Heim, 2009). Although there is no unanimity in its conceptualisation, various definitions have pointed to notions of visibility, openness and accountability, emphasising the social benefits of such exposure (Karlsson, 2010; Singer, 2006). For example, Holtz and Havens (2009) define transparency as “the degree to which an organisation shares information its stakeholders need to make informed decisions” (p. 2).

Within the media field, journalism’s social function is closely tied to the concept of transparency, appreciated for its contribution to establishing and upholding credibility (Craft & Heim, 2009). A more transparent form of journalism - one that explains how the agenda is constructed and the relationship with information sources and openly discloses its financing - is an institution that establishes a relationship of trust with the public. Consequently, transparency is crucial in the ongoing public debate on media responsibilities (Miranda & Camponez, 2022). Transparency can catalyse a renewed professional approach, nurturing a stronger relationship between journalists and their audiences. Transparency in journalistic production can aid in rebuilding any potentially strained relationship with news consumers (Bock & Lazard, 2021; Heim & Craft, 2020). Furthermore, making ownership visible can enhance the autonomy and credibility of journalism (Cappello, 2021).

Transparency is thus a complex and multidimensional concept, which can impact media production conditions such as ownership (Craufurd Smith et al., 2021), journalistic media production (Miranda & Camponez, 2022) and media distribution through algorithmic platforms (Diakopoulos & Koliska, 2017). It is also a principle and a challenge, given the numerous obstacles to its actualisation: intricate ownership mechanisms aggravated by the global movement of financial flows, the inefficiencies and resistance within journalistic institutions or the algorithmic platformisation of society and cultural production (Poell et al., 2022).

Within this broad context of media transparency, ownership regulation holds significant importance. Policies to foster transparency, such as mandating the disclosure of beneficial owners nominally, are based on the assumption that owners can influence the content, professional autonomy and free flow of information (Sjøvaag & Ohlsson, 2019). Such regulations can also address concerns about concentration, commercialisation (profit orientation) and patronage. These phenomena can influence the quality of the journalism produced, thus justifying policies that regulate ownership, particularly regarding transparency. The underlying principle is that “transparency does not restrict ownership, but makes it visible so that the public can make informed choices about how to respond to the content provided” (Picard & Pickard, 2017, p. 29).

There is a growing emphasis on ownership transparency at the European level, which has dictated the emergence of policies at this level. The Council of Europe (2018) has recommended the development of laws that mandate transparency in media ownership for the benefit of pluralism. According to the recommendation, such measures could shed light on cross-ownership, direct and indirect ownership, effective control, and influence. Simultaneously, they aim to ensure an effective and manifest separation between the exercise of authority or political influence over content. Besides soft policy actions (non-binding regulatory strategies based on recommendations, guidelines, resource sharing, etc.), such as commissioning studies on transparency in the European media, the European Commission has also made progress in the legislative field. The revision of the Audiovisual Services directive in 2018 explicitly addresses the principle of ownership transparency. Recently, the European Commission has proposed the European Media Freedom Act, seeking to enforce mandatory disclosure of ownership data and introduce new requirements for allocating State advertising. These new provisions still await approval by the European Parliament and the member States. Moreover, they might undergo profound changes, particularly in light of the recent ruling by the European Court of Justice of the European Union on the disclosure of effective beneficiaries.

On November 22, 2022, a Court ruling invalidated a provision of the 5th Directive on the prevention and penalisation of money laundering in the European Union, that guaranteed public access to information on company owners. The case was referred by a Luxembourg court due to a challenge by that country’s commercial registry, contending that the provision jeopardised the right to privacy. Following this decision, many public databases on owner registration were temporarily suspended. The decision was poorly received by several anti-corruption activists and others, even though the court acknowledged civil society’s and the media’s legitimate interest in accessing this information, particularly in the fight against money laundering. A proposal to amend the directive is now deemed necessary to reconcile the conflicting rights and to make such access operational.

When considering the anti-money laundering directive within the framework of media systems, it highlights a prevailing market reality: the emergence of players such as financial funds and private equity firms with no transparency obligations towards their shareholders or business people linked to autocratic regimes (Dragomir, 2019; Noam, 2018). In Portugal, for example, capital from countries that do not guarantee democratic principles in media companies has already raised concerns (Figueiras & Ribeiro, 2013; Silva, 2014).

The underlying assumption is that excessive media concentration or potential conflicts of interest on the part of owners can only be identified if there is visibility at the ownership level. Transparency is thus an instrument for guaranteeing diversity, as it highlights the different structures behind media services (Cole & Zeitzmann, 2021), clarifying whether citizens receive a spectrum of content offering diverse opinions and viewpoints. In instances where control is lacking or minimal, it becomes more challenging to detect biases or omissions, which can lead to a lack of trust in the media. Research has established a positive association between transparency and trust (Curry & Stroud, 2021). From a market perspective, transparency also offers benefits, contributing to open and fair competition. This principle can safeguard independence, enhancing the quality of media offerings (Cole & Zeitzmann, 2021).

Transparency can be observed in two distinct dimensions: one of an administrative and legal nature and the other of a civic nature (Craufurd Smith et al., 2021). While the civic dimension makes the media accountable to civil society, investors and the general public, the administrative dimension involves companies being open to auditing and monitoring by regulatory bodies and other public agents. Although transparency may not be a pressing concern for audiences and the public under typical media operating conditions (Karlsson & Clerwall, 2019), the second dimension of transparency is expected to yield benefits since regulatory agents and/or the State are, from the outset, more aware of the issues surrounding the performance and management of the media.

Thus, transparency policies cannot be used as a pretext to circumvent other public and regulatory policies in the media sector (Meier & Trappel, 2022). On the contrary, transparency should be the mechanism that delineates where and how the State should intervene. These authors caution that transparency alone does not guarantee market competition or media pluralism. In the same vein, Craufurd Smith et al. (2021) argue that while transparency is necessary, it is insufficient. This principle “can only ever be the starting point - and not the goal - in politics defending the normative ideals of news media in liberal democracies” (Meier & Trappel, 2022, p. 270).

Attaining sufficient levels of transparency can be challenging, primarily due to the difficulty in measuring adequacy in this domain and because the realisation of what it means often remains unachieved. While not questioning the normative value of transparency, its practical implementation in the media industry remains ambiguous. Although the ethical significance of transparency is sustained in the public agenda, the complexity of its implementation and practice must be acknowledged and examined (Bock & Lazard, 2021), as well as the limitations in fully accomplishing the ideal of transparency (Ananny & Crawford, 2018).

It is, therefore, pertinent to investigate how companies operating within the media sector have responded to the new legal framework. Such an analysis can shed light on the actual landscape of its implementation, providing insights into the perceptions and practices of the agents.

3. Promoting Ownership Transparency - The Portuguese Case

On media transparency policies, Portugal stands ahead of most European countries, which have no specific requirements (Craufurd Smith et al., 2021). Several revisions to the media sector laws (including press, radio and television laws) have been introduced to enforce the public disclosure of the nominative composition of capital holders. According to Rabaça (2002), “the principle of transparency is currently among the most effective methods for safeguarding pluralism and preventing concentrations” (p. 419), and this is increasingly becoming the fundamental legal instrument. Meanwhile, since 2015, legislation has specifically addressed transparency obligations at the ownership level: Law No. 78/2015 (Lei n.º 78/2015, 2015), which mandates transparency in media ownership, management and financing. According to this legal provision, ERC must manage a Transparency Portal where citizens can access the list of beneficiaries associated with companies operating in the sector.

The law encompasses, as per Article 6 of ERC statutes (Lei n.º 53/2005, 2005), news agencies, editors of periodicals, radio and television operators, including digital media, and any other entities consistently presenting content subject to editorial treatment and organised as a coherent unit accessible to the public through electronic communications networks. Following the transposition of the Audiovisual Services Directive in 2020, reporting obligations have also extended to on-demand audiovisual service providers. Companies are required to report the shareholders and the chain of ownership of “qualifying holdings” (equal to or greater than 5%), as well as any increase or decrease in the percentage of holdings. The reporting requirements also include details about the composition of the governing bodies and publishing authorities, financial data, and identification of relevant clients and liability holders. Companies can also request confidentiality for the disclosed data, subject to ERC authorisation.

After the law was enacted (Lei n.º 78/2015, 2015) in 2015, ERC launched a platform in April 2016 for companies to comply with the submission of the required information. Over the subsequent three years, the regulatory body and the regulated collaborated to assess and rectify the reporting methods, gradually refining the procedures while considering guidelines on safeguarding personal data (Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social, 2020). In December 2019, the Transparency Portal was finally launched, handling the information provided by companies and making it accessible to the public. A few months earlier, ERC had begun reviewing the confidentiality requests it had received in the interim. Only then (in October 2019) guidelines were established to ensure a consistent understanding within the entity. Requests primarily focused on the sensitivity of the data, as applicants “anticipated potential adverse impacts resulting from the disclosure of information related to the media’s business strategies, revenue structures and the economic and financial sustainability” (Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social, 2020, p. 264).

Beyond the information available through the Transparency Portal, the regulatory reports, issued since 2016, include processed and aggregated information from the companies and organisations registered on the portal. For instance, as of June 20, 2022, 1,848 agencies owned by 1,463 entities were registered, of which 60% primarily engaged in media-related activities (Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social, 2022). These reports also categorise data by industry sector, such as food or religion, shedding light on some ownership structures linked with the respective entities. However, despite public adherence to these directives, the anticipated added value from the principle of transparency remains elusive. As noted by Baptista (2022), “public discussion is limited and fails to contribute to a thorough understanding of the interactions between the media system and political and economic powers” (p. 147).

This situation demands a comprehensive mapping of the reactions following the enactment of the law, both from the regulatory body (responsible for ensuring compliance with legal provisions) and the regulated entities (subject to these obligations). Despite acknowledging critical viewpoints on transparency - not expecting the pursuit of this principle to be a panacea for all the problems or risks affecting the media - it remains essential to assess the outcomes of the law’s implementation.

4. Methodology

This research seeks to understand how the regulated entities (media companies) have complied with legal guidelines (and, above all, what objections they have raised) and how the regulatory body has responded. A document analysis of ERC’s deliberations was conducted to meet the purpose of the research, as these documents encapsulate the core of regulatory activity and the outcomes of the entity’s responses to the behaviour of the regulated entities. A categorical content analysis was performed on the entire corpus of documents extracted from ERC’s website in February 2023 using the keyword “transparency”.

This search produced 99 results. An initial temporal analysis of the deliberations showed that 16 of these documents related to a period before the law was enacted and were therefore excluded. This led to 83 deliberations, out of which 14 were also excluded as they did not relate to the “Transparency Law” of media ownership. From the remaining 69, one concerned a complaint by Impresa about a news item in a media outlet belonging to the Newsplex group, resulting in a parallel process; another concerned the closure of an administrative offence; and three concerned clarifications of the law itself. That left 64 decisions, primarily falling into two situations: (a) requests for confidentiality in disclosing mandatory reporting data by media companies and (b) proceedings opened by ERC concerning non-compliance with reporting obligations.

Consequently, the research focused on an analysis of these 64 decisions. Their initial reading unveiled the following constituent elements, which were transformed into categories for analysis: “date”, “company identification”, and “ERC decision”, further divided into the subcategories related to “mandatory reporting data” or “requests for secrecy”. In order to understand the nature of the companies involved, two other categories were added (“type of media” and “geographical scope”) for which data was collected through an online search of public information.

After the documents were classified, the analysis involved tallying the number of non-compliances within each category (refer to Table 1) and subcategory (refer to Appendix 1 and Table A1), followed by a descriptive statistic analysis. All the regulatory body’s decisions were considered in this count, including those relating to companies in the same economic group and those targeting the same company twice. Additionally, all occurrences were documented, considering that a company might fail to meet more than one reporting obligation or request confidentiality for more than one type of information. It should be noted that ERC did not publish an evaluation form for only two companies, making it impossible to itemise the type of mandatory information missing.

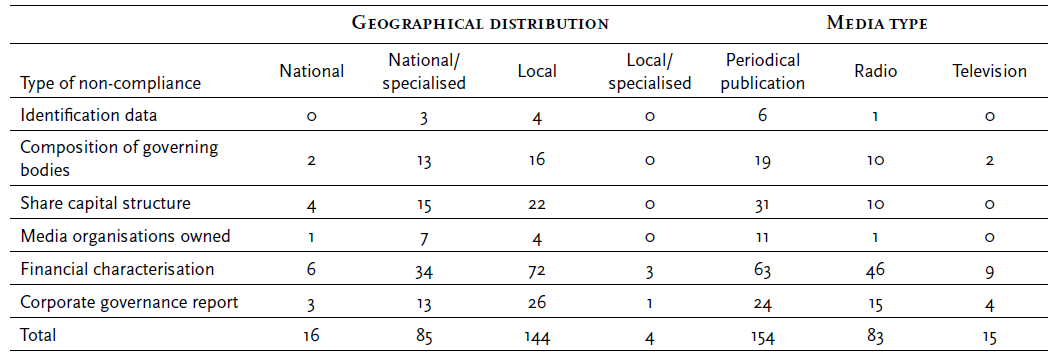

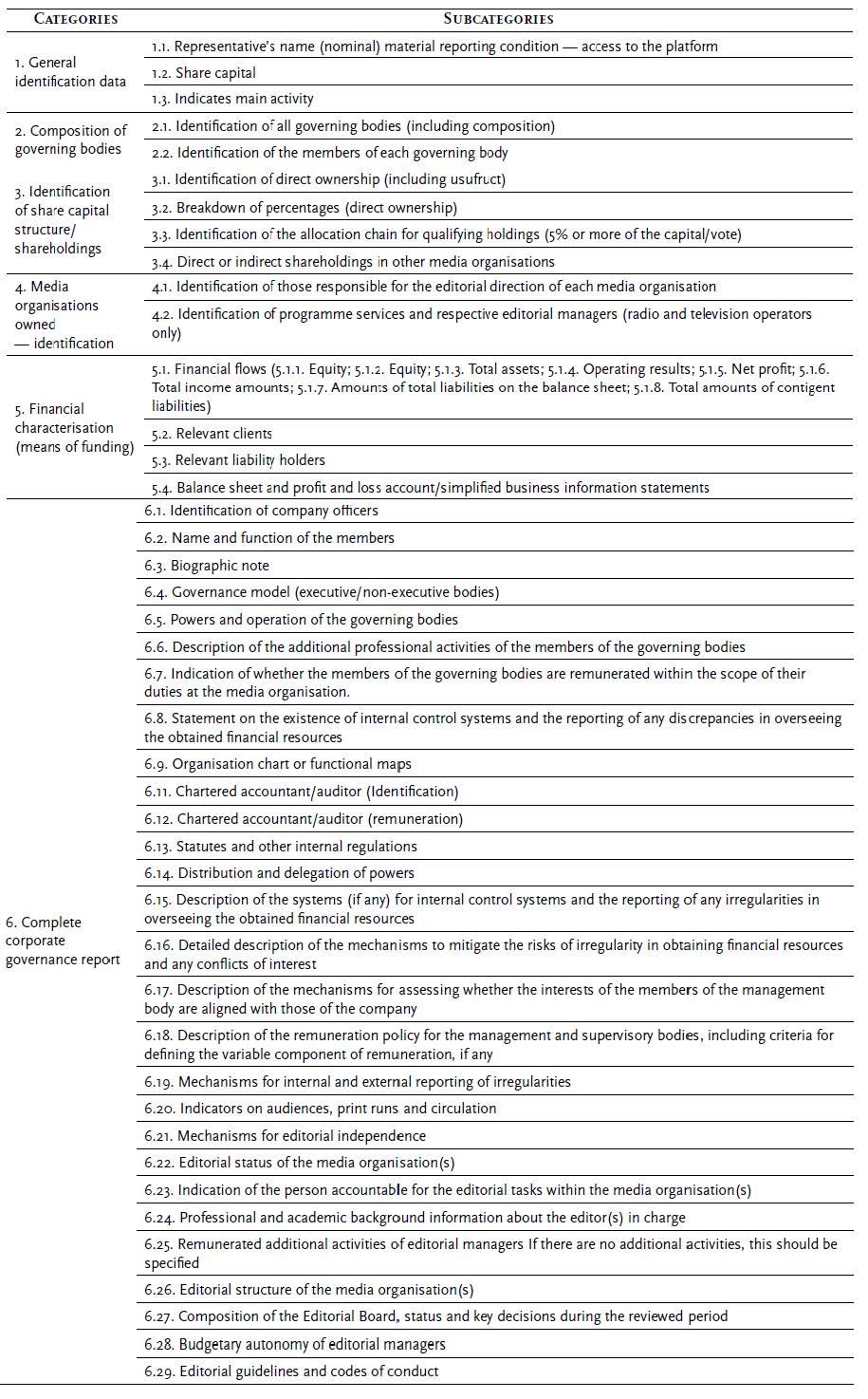

Table 1 Global categorisation of media reporting obligations

Note. Information from the deliberations of Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media analysed, Law 78/2015 (Lei n.º 78/2015, 2015) and Regulation 835/2020 (Regulamento 835/2020, 2020)

In addressing the omission of mandatory reporting data, ERC classifies the degree of compliance as binary: “present” or “absent”, with two exceptions classified as “to be determined”. For the scope of this investigation, it was considered that, in these cases, the duty to provide information had not been fulfilled. As for requests for secrecy, the regulatory authority only reports a decision to decline or partially grant the request (no request was fully granted).

5. Presentation of Results

Thus, the collection yielded 64 decisions involving 59 media companies since three companies were notified twice, and there were two cases of companies belonging to the same business group. These companies are only mentioned in the context of the opening of proceedings for non-compliance with reporting obligations. There are no overlaps between the companies notified of non-compliance with reporting obligations and those that have requested the secrecy of mandatory reporting information.

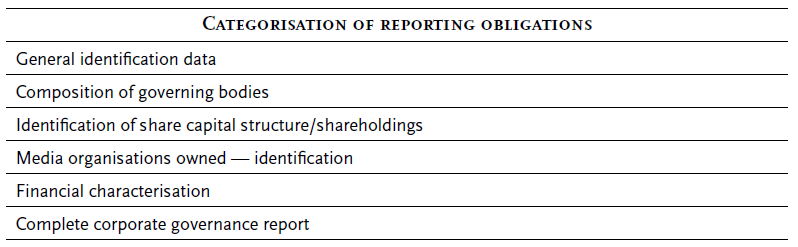

As a result, 48 administrative and/or administrative offence proceedings were opened against 43 companies or business groups for non-compliance with reporting obligations and 16 decisions were issued on requests for confidentiality. In the first year of operation, ERC’s website does not list any deliberations on requests for secrecy; the following year, however, saw the highest number of deliberations: 66% of the total (Table 2).

Table 2 Date of Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media deliberations

Note. Information from the deliberations of Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media analysed

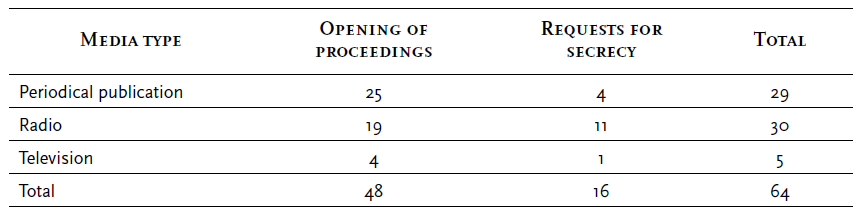

The characterisation of the involved companies highlights two realities: periodicals accounted for 52% of the instances related to non-compliance with reporting obligations, whereas radio stations were notably prominent in requests for secrecy (Table 3). When combining these two categories, the two typologies demonstrate a balanced representation.

Table 3 Breakdown of the companies involved by publication type

Note. Information from the deliberations of Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media analysed

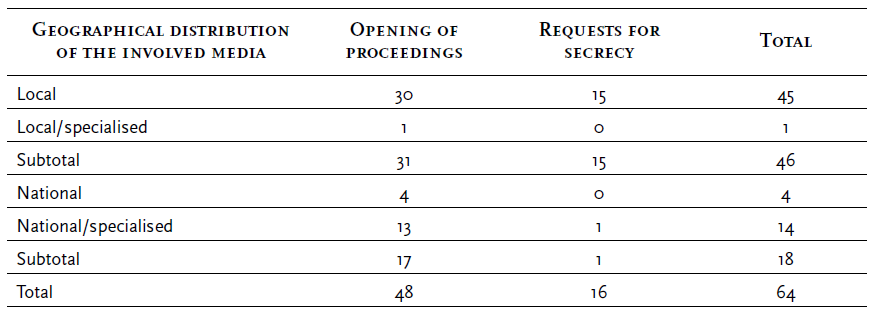

Most of the media involved are locally oriented, constituting 72% of the total (comprising 28 radio stations and 15 newspapers). The remaining 28% operate nationally, particularly within specialised magazine sectors (22% of the overall figure): real estate, tourism, motoring, travel, architecture, economics and religion, among others (Table 4). These specialised magazines are represented by only 12 companies, encompassing 27 periodicals. Regarding audiovisual media, there are three local television news channels and two cable channels (catering to culture and adult segments). Among national titles, only Newsplex, owner of the general information newspapers Inevitável and Pôr do Sol, was notified due to deficiencies in identifying the share capital structure, media outlets owned, financial characterisation and corporate governance data.

Table 4 Geographical distribution of the involved media

Note. Information from the deliberations of Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media analysed

5.1. Opening of Proceedings for Non-Compliance With Reporting Obligations

As noted earlier, out of the 64 reviewed decisions, 48 aimed to open proceedings regarding non-compliance with reporting obligations: 47 administrative offence proceedings (42 of which were suspended for 10 days to allow the regulated entities to provide the lacking information, resulting in case closure, while five were enforced) and one administrative offence proceeding was closed due to the defendant’s insolvency. The number of non-compliances registered, even after the adjustment period granted by the regulatory authority, indicates certain challenges in the coordination between ERC and the regulated entities.

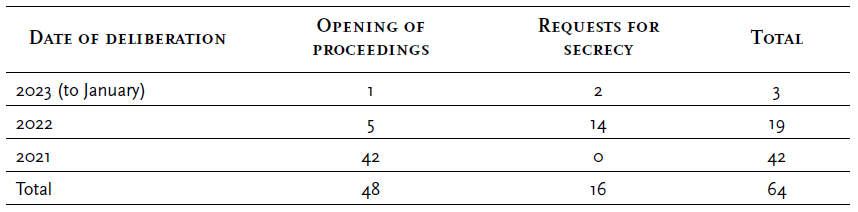

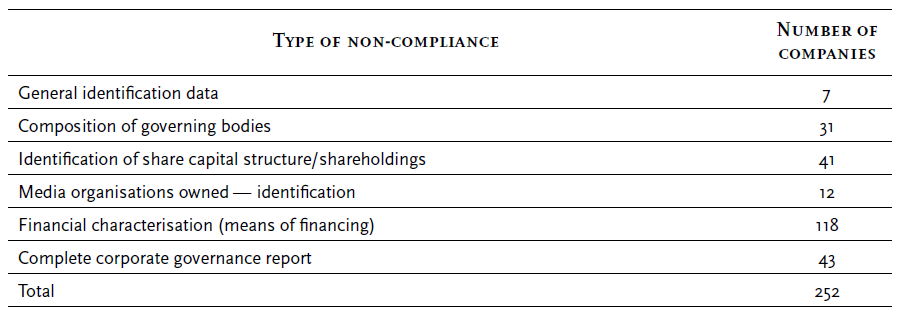

The stipulated legislation requires the publication of 51 pieces of information, categorised into six areas: general data identifying the company and its representative; composition of the governing bodies; identification of the structure of the share capital/shareholdings; identification of the media outlets owned and those accountable for publishing; financial characterisation of the company (means of financing); and a comprehensive corporate governance report (see Appendix). Table 5 shows the subcategories marked in each resolution (a company may be represented in more than one category). Financial information stands out as the category with the highest number of non-compliances, significantly behind identifying the composition of companies’ share capital structure.

Table 5 Classification of non-compliance with declarations

Note. Information from the deliberations of Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media analysed

In the published resolutions, ERC has detailed all categories except the “corporate governance report”, which may be under-represented. In the “financial characterisation” category, the regulatory authority specifies only three subcategories (“financial flows”, “relevant clients”, and “holders of relevant liabilities”) out of a total of 12 mandated by the legislation. This study recorded all the occurrences, acknowledging that a company may fail to comply with multiple reporting obligations.

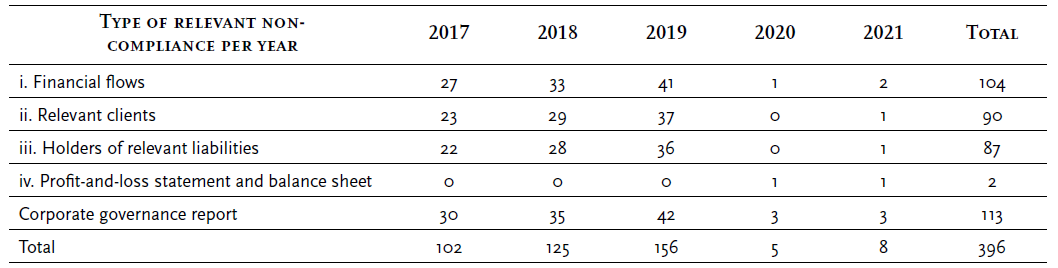

Finally, ERC breaks down the categories “financial characterisation” (and its subcategories) and “corporate governance report” by year. Commencing from 2017, set as the initial year for annual reporting by the regulatory authority, there is a gradual increase in non-compliance count, peaking in 2019. As for 2020 and 2021, the numbers are negligible.

One open case was closed due to the defendant’s insolvency. No available information in the database indicates whether the remaining regulated organisations rectified their non-disclosure within the 10-day deadline or if ERC could pursue the administrative offence further. The data shows that information on financial flows, relevant customers and relevant liability holders is regarded as particularly sensitive (Table 6).

Table 6 Type of non-compliance relating to financial characterisation per year

Note. Information from the deliberations of Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media analysed

Comparing the media type and geographic distribution with the omitted information reveals that local media are the most frequent non-compliers. The same pattern is evident among periodicals (Table 7).

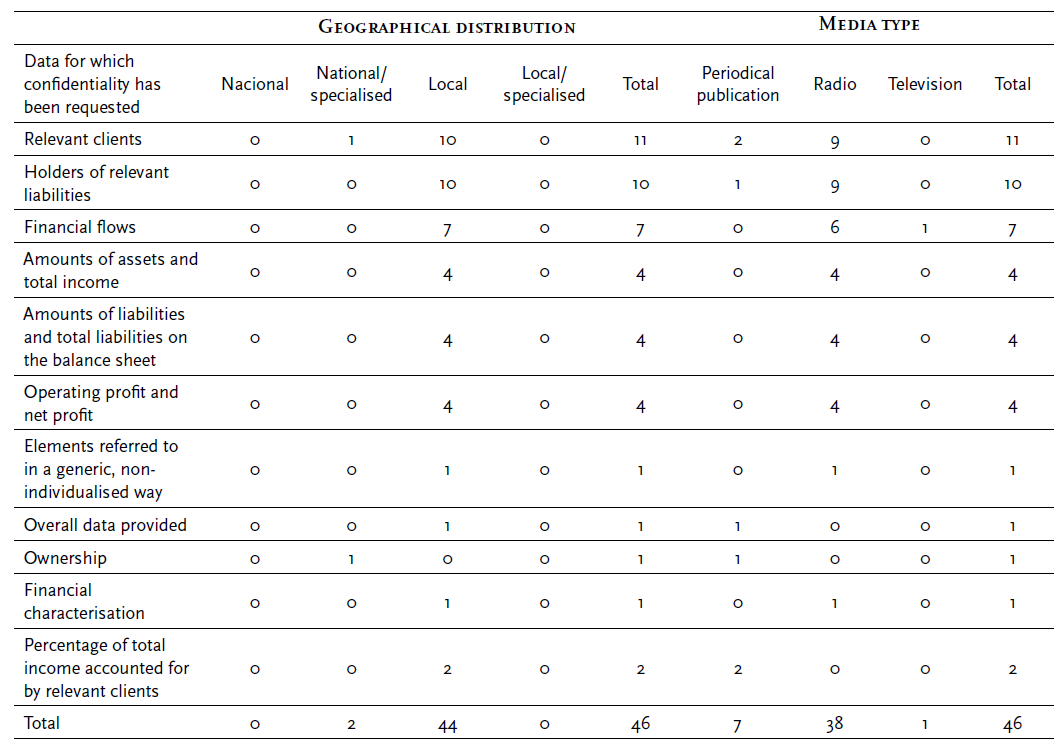

5.2. Request for Confidentiality of Information

Still on transparency, 16 companies requested the confidentiality of 46 mandatory items in the period under review. Notably, as shown in Table 7, relevant clients (11), holders of relevant liabilities (10), and overall financial flows (seven) were the most frequently requested information subcategories. It is worth noting that this aligns with the most frequent type of undisclosed information (see Table 4 and Table 5).

Besides the type of information requested to be kept confidential, ERC only discloses the identity of the requesting company: 10 local radio stations, four local newspapers, one local television station and one national and specialised magazine. Based on this information, shown in Table 8, it is possible to conclude that local companies account for 96% of the confidentiality requests (in line with the methodology applied in the segment on reporting obligations, all occurrences are noted, as a company can request the confidentiality of several types of information). A national specialised media outlet submitted the remaining two requests. There were no requests from national generalist media or local specialised media. Furthermore, radio stations are responsible for the largest count of requests to withhold information.

Table 8 Confidentiality requests by type of media and geographical distribution

Note. Information from the deliberations of Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media analysed

In its decisions on requests to withhold information, ERC refrains from sharing the grounds offered by the applicants, citing its intention to respect the confidentiality requested. For the same reason, it does not disclose the rationale behind the decision, indicating only the decision to reject or partially approve the request (in only one case, involving the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, the owner of Global Difusion, operating six radio stations the request was partially granted, without specifying the identification of associates who do not represent a qualified holding). Furthermore, no provisional measures were enacted.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Independence is a pivotal principle in upholding journalistic quality, and ownership transparency and the financial mechanisms related to the organisations’ activities are possible pathways to ensure this principle. Transparency also makes it possible to examine the landscape of pluralism and diversity within the media sector. However, transparency might conflict with other values, including owners’ privacy or companies’ competitive advantages. This dynamic puts the quality of journalism at risk, as ownership is also the basis for assessing the conditions under which journalistic content is produced. Therefore, assessing the implications of the “Transparency Law”, based on the reaction of economic agents to the new legal framework and the actions of the regulatory authority, provides a deeper understanding of the enforcement of this new tool.

An initial data review shows that most media outlets registered with ERC have generally adhered to the legal requirements, with the regulatory body needing to intervene in only a limited number of cases compared to the overall media landscape. However, analysing the interactions between the regulatory authority and the companies highlights other noteworthy patterns that warrant further exploration. Firstly, we should note the absence of deliberations involving major business groups responsible for the country’s main media outlets. There seem to have been no difficulties for these major operators in complying with the legal precepts on transparency. That may suggest, contrary to concerns about potential harm to companies’ competitive advantage (De Laat, 2018) or clashes with the interests of owners and shareholders (Henriques, 2013), that these major operators either welcomed the new transparency guidelines without seeing them as problematic or did not foresee any negative public reaction to the disclosed data.

Of course, three major media groups in Portugal (Impresa, Media Capital and Cofina) are publicly listed, which already entails significant reporting obligations. Nevertheless, despite ERC’s publication of an annual report and consolidated data on media ownership in Portugal, there has yet to be any debate, action or official stance by public authorities, notably the Government. It should be noted that, while processing data on the nationality of media ownership, ERC has demonstrated the existence of capital from countries with autocratic regimes in various media (Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social, 2022), including Angola and China, a situation that has already been analysed in scientific works (Figueiras & Ribeiro, 2013; Silva, 2014), yet the State has expressed no public concerns. Furthermore, the fact that 40% of the companies operating in the sector do not primarily focus on media activities and the potential implications regarding conflicts of interest (see, for example, Noam, 2018) have not been publicly addressed.

ERC has effectively collected the information required by law, taking action against non-compliant companies and making the data accessible on the portal. However, fostering transparency is not an end in itself. Law 78/2015 (Lei n.º 78/2015, 2015) explicitly highlights this in Number 1 of Article 1, stating that the regulation of property at this level is “aimed at promoting freedom and pluralism of expression and safeguard its editorial independence from political and economic powers”, an objective that ERC meets according to its statutes. In other words, one would expect that increased visibility into companies’ ownership and financial mechanisms would stimulate reflection on the risks inherent in the Portuguese media landscape.

However, the fact that ERC publishes data on the Transparency Portal and extracts information annually for its reports has not signalled any significant change in the media ownership landscape in Portugal: there have been no public statements suggesting that the “Transparency Law” has influenced the level of ownership concentration, nor has it been cited as a factor requiring action to enhance pluralism and diversity. Consequently, ERC has not issued any deliberation or recommendation (which, it should be remembered, has the legal powers to do so) resulting from the “Transparency Law”, addressing media companies’ ownership of capital (nationality or main sector of activity) or entities with financial clout. Nor has the Government, political parties or other civil society organisations taken any position on which ERC should have commented. The lack of action in this direction leads to the conclusion that the law is fairly ineffective in promoting public engagement in discussing the risks associated with media ownership in Portugal.

For instance, the results show that breaches adhering to reporting requirements and requests for confidentiality affect mainly small markets in local segments (therefore geographically limited) or niche specialised magazines. This conclusion raises a question: should distinct market realities, such as those in media markets, be treated similarly, especially when the industry is significantly influenced by scale (Noam, 2014; Picard, 2005)? On the one hand, it prompts the need to determine whether the regulatory demands are sufficient for larger, well-resourced companies with technical capacity (particularly accounting); on the other hand, it is necessary to investigate the potential challenges for smaller entities with limited technical capabilities to fulfil accounting and financial obligations. This study highlights the difficulty in achieving an “ideal of transparency” (Ananny & Crawford, 2018) because, as the scale is an important variable, doubts arise regarding whether a singular transparency standard can equitably serve all market players.

The issue of confidentiality, requested by some companies, is also noteworthy, especially when considering which data is requested the most: liability holders and relevant clients. Additionally, one of the primary sources of non-compliance revolves around disclosing the companies’ means of financing. Thus, the problem may lie not with media owners and their right to privacy but with external agents that could compromise media independence. Hence, it is vital to assess whether these breaches and requests are linked to economic and financial fragility cases and whether they could lead to situations of media capture2 (Dragomir, 2019; Meier & Trappel, 2022) by political and economic agents. This concern is particularly relevant when discussing the quality of journalism, as it involves a very relevant and particularly fragile type of journalism: local journalism (Jenkins & Jerónimo, 2021). However, ERC does not disclose the reasons invoked in the confidentiality requests submitted, preventing external scrutiny, nor has it promoted a public discussion on this topic.

This study underscores, as several authors have previously highlighted that transparency alone does not deliver the expected outcomes: it is necessary yet insufficient (Craufurd Smith et al., 2021; Meier & Trappel, 2022). By examining the data, it becomes evident that a role remains for regulation and public policies in an era of transparency. For instance, there is a crucial need to explore the influence of ownership on the media, particularly concerning situations of foreign capital from autocratic countries or other economic sectors. Simultaneously, the precarious state of local media should draw the attention of regulators and public decision-makers: a more comprehensive analysis of confidentiality requests could unveil the actual risk of media capture and suggest potential strategies for fortifying and upholding media independence.

Conversely, ownership transparency alone does not address the appropriateness or credentials of ownership, nor has this aspect been a subject of discussions within ERC. Thus, visibility cannot guarantee the suitability of the conditions for producing quality journalism. In other words, the administrative and legal dimensions of transparency are met in their structure. However, there is a lack of broad reflection on transforming it into a tool serving public communication policies that foster, for instance, independence and diversity in journalism.

Another issue relates to the scope of the law: it solely applies to companies involved in content production and organisation, overlooking the potential risks in distribution, whether it is still analogue or digital (Russell, 2019). This gap could become increasingly critical, particularly with the algorithm-based nature of the main news consumption platforms, potentially leading to biased access to information. Furthermore, these legal limitations might elude situations that compromise market competition, especially as production agreements with distribution (whether digital intermediaries or physical networks) may not be scrutinised. Transparency in terms of ownership of production does not solve the need for transparency in terms of distribution.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that this study, focusing solely on the interaction between companies and the regulatory authority, does not encompass all the dimensions of the companies’ actions regarding ownership transparency. Another limitation of this work, when considering the relationship between transparency and the quality of journalism, is that some companies considered in this mapping may not be solely journalistic: they are media companies, but, for example, some radio stations may be classified as music radios. However, it should be noted that this classification does not prevent the broadcasters from including local information; it just does not require a periodicity in terms of news broadcasts. Despite these limitations, the study of ERC’s decisions provides relevant insights into the relationship between companies and ownership transparency, particularly because it highlights the invisibility of the legal framework and the state. Compliance with the principle of transparency might have obscured the need for active policies to promote quality in journalism by strengthening the conditions for its production.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programme funding).

REFERENCES

Aalberg, T., & Curran, J. (2012). How media inform democracy. Routledge. [ Links ]

Allen, D. S. (2008). The trouble with transparency: The challenge of doing journalism ethics in a surveillance society. Journalism Studies, 9(3), 323-340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700801997224 [ Links ]

Ananny, M., & Crawford, K. (2018). Seeing without knowing: Limitations of the transparency ideal and its application to algorithmic accountability. New Media & Society, 20(3), 973-989. [ Links ]

Baptista, C. (2022). Transparency in Portuguese media. Observatorio (OBS*), 16(2), 138-149. [ Links ]

Bock, M. A., & Lazard, A. (2021). Narrative transparency and credibility: First-person process statements in video news. Convergence, 28(3), 888-904. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211027813 [ Links ]

Cage, J., Godechot, O., Fize, E. , & Porras, M. C. (2017). Who owns the media? The Media Independence project. Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire d’évaluation des Politiques Publiques. [ Links ]

Cappello, M. (Ed.). (2021). Transparency of media ownership. European Audiovisual Observatory. [ Links ]

Cole, M. & Zeitzmann, S. (2021). Conclusions. In M. Cappello (Ed.), Transparency of media ownership (pp. 115-118). European Audiovisual Observatory. [ Links ]

Council of Europe. (2018, 7 de março). Recommendation CM/Rec(2018)1[1] of the Committee of Ministers to member States on media pluralism and transparency of media ownership. https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectId=0900001680790e13 [ Links ]

Craft, S., & Heim, K. (2009). Transparency in journalism: Meanings, merits, and risks. In L. Wilkins & C. G. Christians (Eds.), The handbook of mass media ethics (pp. 217-228). Routledge. [ Links ]

Craufurd Smith, R., Klimkiewicz, B., & Ostling, A. (2021). Media ownership transparency in Europe: Closing the gap between European aspiration and domestic reality. European Journal of Communication, 36(6), 547-562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323121999523 [ Links ]

Curry, A. L., & Stroud, N. J. (2021). The effects of journalistic transparency on credibility assessments and engagement intentions. Journalism, 22(4), 901-918. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919850387 [ Links ]

De Laat, P. B. (2018). Algorithmic decision-making based on machine learning from big data: Can transparency restore accountability? Philosophy & Technology, 31(4), 525-541. [ Links ]

Diakopoulos, N., & Koliska, M. (2017). Algorithmic transparency in the news media. Digital Journalism, 5(7), 809-828. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1208053 [ Links ]

Dragomir, M. (2019). Media capture in Europe. Media Development Investment Fund. [ Links ]

Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social. (2020). Relatório de regulação 2019. https://www.flipsnack.com/ercpt/erc-relat-rio-de-regula-o-2019/full-view.html [ Links ]

Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social. (2022). Relatório de regulação 2021. https://www.erc.pt/download.php?fd=12855&l=pt&key=bc4ddcc6d69ae573d5f148d6c3659094 [ Links ]

Figueiras, R., & Ribeiro, N. (2013). New global flows of capital in media industries after the 2008 financial crisis: The Angola-Portugal relationship. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(4), 508-524. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161213496583 [ Links ]

Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J., & Roberts, B. (2017). Policing the crisis: Mugging, the State and law and order. Bloomsbury Publishing. [ Links ]

Heim, K., & Craft, S. (2020). Transparency in journalism: Meanings, merits, and risks. In L. Wilkins & C. G. Christians (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of mass media ethics (pp. 308-320). Routledge. [ Links ]

Henriques, A. (2013). Corporate truth: The limits to transparency. Routledge. [ Links ]

Holtz, S., & Havens, J. C. (2009). Tactical transparency: How leaders can leverage social media to maximize value and build their brand. John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J., & Jerónimo, P. (2021). Changing the beat? Local online newsmaking in Finland, France, Germany, Portugal, and the UK. Journalism Practice, 15(9), 1222-1239. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1913626 [ Links ]

Karlsson, M. (2010). Rituals of transparency: Evaluating online news outlets’ uses of transparency rituals in the United States, United Kingdom and Sweden. Journalism Studies, 11(4), 535-545. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616701003638400 [ Links ]

Karlsson, M. (2020). Dispersing the opacity of transparency in journalism on the appeal of different forms of transparency to the general public. Journalism Studies, 21(13), 1795-1814. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1790028 [ Links ]

Karlsson, M., & Clerwall, C. (2019). Cornerstones in journalism: According to citizens. Journalism Studies, 20(8), 1184-1199. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1499436 [ Links ]

Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2001). The elements of journalism: What news people should know and the public should expect. Three Rivers Press. [ Links ]

Lacy, S., & Rosenstiel, T. (2015). Defining and measuring quality journalism. Rutgers School of Communication and Information. [ Links ]

Lei n.º 53/2005, de 08 de novembro, Diário da República n.º 214/2005, Série I-A de 2005-11-08 (2005). https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/53-2005-583192 [ Links ]

Lei n.º 78/2015, de 29 de julho, Diário da República n.º 146/2015, Série I de 2015-07-29 (2015). https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/78-2015-69889523 [ Links ]

Lindgren, A., Jolly, B., Sabatini, C., & Wong, C. (2019). Good news, bad news: A snapshot of conditions at smallmarket newspapers in Canada. National News Media Council. [ Links ]

Meier, W. A., & Trappel, J. (2022). Media transparency: Comparing how leading news media balance the need for transparency with professional ethics. In J. Trappel & T. Tomaz (Eds.), Success and failure in news media performance: Comparative analysis in the Media for Democracy Monitor 2021 (pp. 255-273). Nordicom; University of Gothenburg. https://doi.org/10.48335/9789188855589-12 [ Links ]

Miranda, J., & Camponez, C. (2022). Accountability and transparency of journalism at the organizational level: News media editorial statutes in Portugal. Journalism Practice, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2022.2055622 [ Links ]

Noam, E. (2014). Does media management exist? In P. Faustino, E. Noam, C. Scholz, & J. Lavine (Eds.), Media industry dynamics (pp. 27-41). Formalpress | Media XXI. [ Links ]

Noam, E. (2018). Beyond the mogul: From media conglomerates to portfolio media. Journalism, 19(8), 1096-1130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917725941 [ Links ]

Picard, R. (2005). Unique characteristics and business dynamics of media products. Journal of Media Business Studies, 2(2), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2005.11073433 [ Links ]

Picard, R., & Pickard, V. (2017). Essential principles for contemporary media and communications policymaking. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [ Links ]

Poell, T., Nieborg, D. B., & Duffy, B. E. (2022). Platforms and cultural production. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Rabaça, C. (2002). O regime jurídico-administrativo da concentração dos meios de comunicação social em Portugal. Almedina. [ Links ]

Regulamento 835/2020, de 2 de outubro, Diário da República n.º 193/2020, Série II de 2020-10-02 (2020). https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/regulamento/835-2020-144456439 [ Links ]

Russell, F. M. (2019). The new gatekeepers: An institutional-level view of Silicon Valley and the disruption of journalism. Journalism Studies, 20(5), 631-648. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1412806 [ Links ]

Schiffrin, A. (2018). Introduction to special issue on media capture. Journalism, 19(8), 1033-1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917725167 [ Links ]

Schudson, M. (2008). Why democracies need an unlovable press. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Silva, E. C. e. (2014). Crisis, financialization and regulation: The case of media industries in Portugal. The Political Economy of Communication, 2(2), 47-60. [ Links ]

Singer, J. (2006, 10-13 de agosto). Truth and transparency: Bloggers’ challenge to professional autonomy in defining and enacting two journalistic norms [Apresentação de comunicação]. Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Anaheim, Estados Unidos da América. [ Links ]

Sjøvaag, H., & Ohlsson, J. (2019). Media ownership and journalism. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-839 [ Links ]

Strömbäck, J. (2005). In search of a standard: Four models of democracy and their normative implications for journalism. Journalism Studies, 6(3), 331-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700500131950 [ Links ]

Trappel, J., & Tomaz, T. (2021). Democratic performance of news media: Dimensions and indicators for comparative studies. In J. Trappel & T. Tales (Eds.), The media for democracy monitor 2021: How leading news media survive digital transformation (Vol. 1). Nordicom; University of Gothenburg. [ Links ]

1“Media capture” is a concept that refers to situations in which political power or other interests interconnected with political power condition or control the actions of the media (Schiffrin, 2018).

Appendix

Before April 2021, the reporting model used by the Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media only included three of the subcategories under the “financial characterisation” category: “financial flows”, “relevant customers”, and “holders of relevant liabilities”. In this research, only the subcategories were considered whenever the regulatory authority marked both the category and subcategories. When it only marked the category, it was assumed that all three subcategories were omitted.

As of April 2021, a comprehensive table listing all the categories and subcategories provided in the legislation was introduced for public reference (Table A1). The new reporting model was implemented for only five companies, and the occurrences were assigned to the respective category for consistency in the methodological standardisation. Finally, the categories and subcategories encompassing “financial characterisation” and the category “corporate governance report” were broken down by calendar year.

Received: April 04, 2023; Accepted: October 24, 2023

texto en

texto en