Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicação e Sociedade

versión impresa ISSN 1645-2089versión On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.44 Braga dic. 2023 Epub 25-Oct-2023

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.44(2023).4828

Varia

Portuguese Party Leaders on Twitter: Interactions and Media Hybridisation Strategies

1 Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia, Escola de Sociologia e Políticas Públicas, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

Este estudo procura perceber até que ponto os líderes partidários portugueses utilizam as possibilidades de interação acessíveis no Twitter, nomeadamente o retweet, menção a outro utilizador e ligação web para outros endereços, e entender qual é a rede de ligações que é criada - se dentro do próprio partido, se aberta a protagonistas partidários de outras forças políticas ou a cidadãos. Adicionalmente, verificamos como é que, através do Twitter, os atores políticos põem em prática uma estratégia enquadrada no modelo mediático híbrido, estabelecendo ligações para os chamados “meios tradicionais de comunicação”, como jornais, rádio e televisão. Os dados são obtidos a partir de uma recolha de tweets publicados por quatro líderes partidários portugueses, do Partido Socialista, Partido Social Democrata, Bloco de Esquerda e Chega, em períodos específicos de 2021 e 2022, posteriormente sujeitos a análise de conteúdo e trabalhados informaticamente através do programa MAXQDA. A pesquisa revelou que todos os líderes utilizam as possibilidades de interação do Twitter, mas com intensidades diferentes. Verificámos que apostam numa estratégia de comunicação híbrida, fazendo convergir na plataforma do Twitter conteúdos dos média tradicionais. A partir dos dados obtidos foi possível estabelecer uma tipologia de estratégias de comunicação postas em prática pelos líderes partidários no Twitter, bem como identificar e caracterizar as possibilidades que as interações mediáticas, realizadas pelos líderes partidários, podem assumir na arena do Twitter.

Palavras-chave: atores políticos; Twitter; interação no Twitter; sistema mediático híbrido

This study aims to understand to what extent Portuguese political party leaders use the interactions accessible on Twitter, namely the retweets, mentions of other users and hyperlinks, and to observe which connection networks are created - whether within the party or outside of it, such as citizens or political actors from other parties. Additionally, we verify how political actors use Twitter to implement a strategy in the hybrid media system model, establishing links to “traditional media” such as newspapers, radio, and television. The data comprises tweets published by four Portuguese party leaders, from Partido Socialista, Partido Social Democrata, Bloco de Esquerda and Chega, during 2021 and 2022, subsequently subject to content analysis using the MAXQDA program. The research revealed that all leaders use Twitter’s interaction possibilities but with different intensities. We verified that they all employ a hybrid communication strategy by converging traditional media content in the Twitter platform. We establish a typology of communication strategies party leaders implement on Twitter from the obtained data. We also identify and characterise the possibilities that media interactions conducted by party leaders can assume in the Twitter arena.

Keywords: political actors; Twitter; Twitter interaction; hybrid media system

1. Introduction

The communication landscape has changed profoundly in recent decades, significantly impacting political communication. During the second half of the 20th century, political campaigns primarily relied on mass media - television, radio, and print (Norris, 2000), considered central elements for successful communication (Burton et al., 2015; Stromer-Galley, 2014). Political communication was thus fundamentally a mediated process, filtered through channels such as the media and political parties, which bridge leaders to the public (Pfetsch & Esser, 2012).

This scenario has taken on new contours with the advent of social networks or social media (Murthy, 2012), which have quickly been adopted and integrated into the communication strategies of political actors and parties across various ideological spectrums and latitudes.

The innovations in how political actors, the media and citizens - central elements of political communication (McNair, 2017) - interact through digital communication have prompted some authors to suggest the emergence of a fourth age of political communication (Blumler, 2013). This era is manifested by the systematic combination of interactive and network-based digital communication features within a pre-defined and user-friendly digital architecture, which has emerged on the web through, for example, practices like blogging (Enjolras, 2014). Indeed, the internet has revolutionised the political arena, significantly altering the speed and scope of communication (Castells, 2011). Social media has become a new player in the world of political campaigns (StromerGalley, 2014).

Enjolras (2014) points out that this new media-centred communication model entails radical changes relative to the communication channels (from few to many), audience (from unified to diversified), transmission (from one-way to interactive), and user’s role (from passive to active). These transformations affecting the dominant communication model in advanced societies affect all forms of communication, including political communication (Enjolras, 2014). Thus, on top of direct contacts, rallies, debates and television interviews, communication methods prevalent in the 20th century that remain so today, tools such as Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and, among others, Twitter1, have added new avenues of communication. Consequently, integrating social media into politics now coexists with traditional media and has profoundly transformed how voters make their decisions regarding their chosen leaders (Gainous & Wagner, 2014).

By enabling access to millions of potential voters and facilitating direct interaction with fellow politicians and citizens, social networks have established an extra political platform for campaigns (Baumman et al., 2016). Hence, candidates and political parties increasingly employ social media to produce and disseminate their messages, seeking to influence voters’ perceptions and behaviour directly (Zamora-Medina et al., 2017), bypassing journalistic mediation (Cammaerts, 2012).

In this context, Twitter has a set of characteristics that make it a particularly interesting tool for political use. On the one hand, it facilitates the immediate, rapid and widespread dissemination of information (Kwak et al., 2010); on the other, its open and horizontal nature and its ability to engage in real-time debates on various issues (Lee et al., 2016) have made it a platform with a notable impact on the process of shaping public discourse. In other words, Twitter enables broad (one-to-many) and interactive communication, which calls for user participation, stimulating network dialogue (Graham et al., 2013).

Axel Bruns (2012) states that Twitter is relatively flat and simple: messages from users are either public and visible to all (even to unregistered visitors using the Twitter website) or private and visible only to approved “followers” of the sender; there are no more complex definitions of degrees of connection (family, friends, friends of friends) as they are available in other social networks. Tweets’ nature is “globally public by default” (Bruns, 2012, p. 1324), allowing discussions on specific topics to be automatically organised through shared conversation markers. The short format of each tweet, initially 140 and currently 280 characters, could be seen as a limitation to debate. However, according to Boyd et al. (2010), this characteristic can be an advantage: “the brevity of messages allows them to be produced, consumed, and shared without a significant amount of effort, allowing a fast-paced conversational environment to emerge” (p. 10). From an optimistic standpoint, Twitter would make it possible to reduce the distance between citizens and politics (Coleman & Blumler, 2009), which is evident in areas such as reducing electoral abstention by encouraging voter engagement in debates on public issues and promoting their active involvement in politics. However, certain studies cast doubt on its real influence in determining the most relevant issues in public opinion (Calvo & CamposDomínguez, 2016).

The rise of new media and its growing impact has led to a distinction between new and traditional media. However, this division has been challenged by Chadwick (2013), who viewed the “new” and “old” dichotomy as inaccurate and misleading. Instead, he argued that we are witnessing a convergence of practices and strategies between new and traditional media platforms, forming a hybrid media system.

2. Hybrid Media System

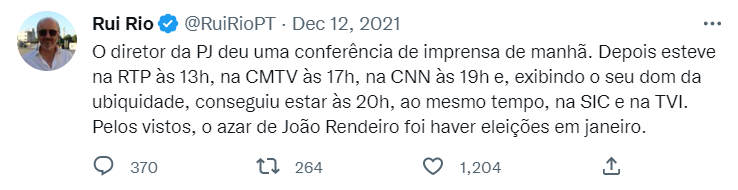

On December 12, 2021, during the pre-campaign for the legislative elections in Portugal, the leader of the Partido Social Democrata (PSD; Social Democratic Party), Rui Rio, posted a text on Twitter (Figure 1) that triggered extensive responses within the Portuguese media and political sphere.

Source. From O diretor da PJ deu uma conferência de imprensa de manhã. Depois esteve na RTP às 13h, na CMTV às 17h [Tweet], by Rui Rio [@RuiRioPT], 2021, Twitter. (https://twitter.com/RuiRioPT/status/1470003993892036617)

Figure 1. Rui Rio’s tweet on the communication strategy of the director of the Judicial Police

Rui Rio was commenting on the interviews given by the national director of the Judicial Police to television networks following the arrest of a former banker. The main Portuguese media outlets (Dinis, 2021; PCP Acusa Rio de Querer “Dar Ordens à PJ” Sobre “Quem Pode ou Não” Ser Detido, 2021; Rui Rio Sugere que Calendário Eleitoral Influenciou Prisão de Rendeirot, 2021) reported on the tweet that dominated more than a third of a 30-minute interview with Rui Rio himself on RTP, two days later (RTP Play, 2021). Even the President of the Republic referred to the tweet (Conceição, 2021). This emphasises that a mere 220 characters shared on the social platform Twitter managed to gain significant coverage in television, radio, and newspapers. A post on a new medium became headline news and “fuelled” the traditional media. This exemplifies the concept of communication of communication where journalists produce news “based on what has already been shared by individuals or organisations through the various forms of media available” (Cardoso, 2023, p. 288). This case is also a demonstration of the dynamics of what Chadwick (2013) defines as a “hybrid media system”, characterised by the amalgamation of media platforms that have been used for decades and those that have appeared more recently. The outcome is the blend of old and new media within a media system where clear distinctions are dissolving and hard to establish (Chadwick, 2013).

Political communication processes will take on new contours. Within a hybrid media system, political communication unfolds as a dynamic, evolving process concerning multiple actors interacting in response to one another through different media outlets and according to many different media principles (Chadwick, 2013). In this context, Twitter is just part of a growing and increasingly complex media ecology encompassing traditional media’s political coverage and political-related interactions across various online channels (Chadwick, 2013).

In the everyday communication practices of political actors on Twitter, hybridisation can manifest in several ways. One such manifestation involves referring to other media, which could entail linking to content like published articles, broadcast reports, photos, or excerpts from television and radio appearances. It might also involve announcing upcoming appearances on programs to enhance their reach and audience or providing links to newspaper news articles and comments. These forms of convergence allow the political actor to directly inform their followers without any mediation about their past and future appearances in other media and to comment on or advertise the content presented in those media, particularly those that directly concern them. This is relevant in political communication strategy: through Twitter, nothing remains limited to its original post, and should the party leader choose to do so, they can respond to anything published.

Aware of this fact, party communication machines, especially during election campaigns, use Twitter and other social media tools regularly and simultaneously with traditional media to engage with voters and influence news cycles and campaign narratives (Kreiss, 2014; Parmelee & Bichard, 2012). The advantage of such an approach lies in its ability to reach voters who are not actively seeking political information but, when using social media, might be accidentally exposed to news and campaign information posted by friends and connections on platforms such as Twitter (Morris & Morris, 2017).

Several studies have explored how political parties use Twitter in their communication strategies, revealing distinctions between recently established and long-standing parties. For instance, Amparo López-Meri et al. (2017) noted a greater Twitter presence among new political forces, citing the following reasons: emerging parties, with less access to traditional media than long-standing parties, aim to maximise the visibility of their appearances in prominent media outlets, particularly on television, by using Twitter; hybridisation is used to get many retweets and “likes” to ensure a double effect: obtaining better publicity and becoming a topic of interest for the media by building a large audience; the parties seek to benefit from the legitimising power of mainstream media, leveraging their appearances in traditional media to present themselves as a credible, valid, and acceptable political option (López-Meri et al., 2017). Despite being rooted in social media, emerging parties are also aware of the importance of mainstream media in modern society and the need to bridge the gap between old and new media (CaseroRipollés et al., 2016). In a similar vein, Ramos-Serrano et al. (2016) observed that in the 2014 European elections in Spain, traditional political parties primarily employed Twitter as a one-way communication tool, while new parties took better advantage of Twitter’s interactive features. Authors such as Jurgens and Jungherr (2015) have also identified differences in Twitter usage strategies between traditional and new parties.

3. Connections and Interactivity on Twitter

As a communication tool, Twitter opens up a whole new field of interactive possibilities. In addition to posting texts and images (photos, graphic compositions or videos) and sending direct messages, the platform includes a set of features through which the user can connect and communicate with other users in several different ways (Bruns & Burgess, 2012), for example through mechanisms such as retweeting, mentioning other users and sharing links to external content - hyperlinks. Within a networked public space, Twitter allows one-to-one, one-to-many and many-to-many communication (Enjolras, 2014).

Interactivity can be defined as the capacity of communication systems to initiate the exchange of messages among participants, resembling a form of interpersonal communication (Rafaeli & Sudweeks, 1997). Stromer-Galley (2004) distinguishes between interactivity as a process - the focus is on the interaction between people; and interactivity as a product - the focus is on interaction mediated through technology.

López-Rabadán and Mellado (2019) note that the existence of bidirectional or multidirectional feedback is a prerequisite of the interactive experience, which is also characterised by the existence of a mediated channel, interchangeable roles among the participants, and a strong “third-order dependence” (p. 3; the need to know, and to be consistent with the information previously shared by the interlocutors). Thus,

social media (webs, blogs and social networks) are perceived as platforms of high interactivity compared to traditional media, which are more limited in their feedback ability with the audience, at least in their traditional media platforms. (López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019, p. 3)

These authors draw attention to two key concepts: “reciprocity”, which implies real equality of treatment between individuals, and “responsiveness”, which is understood as the not-necessarily materialised possibility of interaction (Kiousis, 2002; Lee et al., 2016). Other authors suggest that the communicative dynamic on Twitter relates to these two concepts since they allow direct interactions and reciprocal interactions among users without the need for a full-fledged dialogue (Artwick, 2013; Lewis et al., 2014).

García-Ortega and Zugasti-Azagra (2018) rightly point out that Twitter’s significant role in political communication stems from the fact that it allows interactivity, which makes it possible to break with previous communication models based on one-way communication. Like other social networks, Twitter enables, for example, two-way communication between citizens and political leaders without the need for the mediating action of traditional journalistic media (Maarek, 2011). However, some research points out that Twitter’s interactive potential between politicians and citizens never materialises, and when it does, it is limited. This limitation can be more pronounced during election campaigns, as political actors prefer controlled interaction (Stromer-Galley, 2014).

Christensen (2013) referred to the notion of a “conversational ecology” in this context of multiple interaction possibilities. This author considers, for example, that retweeting is more than just simple information distribution but also a more complex social engagement whereby the retweet is

a form of information diffusion and a means of participating in a diffuse conversation as well as an act “to validate and engage with others;” thus, regardless of why users embrace retweeting, through broadcasting messages, they become part of a broader conversation. (Christensen, 2013, p. 651)

On the other hand, “exposure to a politician’s microblog page increased a sense of direct interaction ( … ), which improved both overall impressions and the vote intention” (Lee & Shin, 2012, p. 516), especially considering less affiliative individuals.

Hence, ultimately, we can consider that we are dealing with a new social sphere, the Twittersphere - where a group of individuals come together to share information and experiences (Moinuddin, 2019). This sphere allows users of digital tools to engage more directly in public affairs through direct communication channels and interactions with political actors, fostering citizen-to-citizen communication without the intermediary of traditional media (Stieglitz & Dang-Xuan, 2012). This environment has its own conversational attributes.

Because Twitter’s structure disperses conversation throughout a network of interconnected actors rather than constraining conversation within bounded spaces or groups, many people may talk about a particular topic at once, such that others have a sense of being surrounded by a conversation, despite perhaps not being an active contributor. (Boyd et al., 2010, p. 1)

As such, “social media has enabled conversations to occur asynchronously and beyond geographic constraints, but they are still typically bounded by a reasonably well-defined group of participants in some sort of shared social context” (Boyd et al., 2010, p. 1).

This study interprets the concept of interaction on Twitter as a political actor’s strategic communication decision to include in their Twitter feed: (a) Twitter content produced by other users through retweets; (b) references to other users of the platform with a direct link using (@) mentioning their name; and (c) links to external content produced by others, namely traditional media, by including web addresses. It is worth noting that a single tweet can incorporate one, two, or all three of these connection possibilities. This type of interaction has a very relevant characteristic for political communication: by initiating a “conversation” with other users, the political actor is able to have this contact witnessed and eventually participated in by their followers, thus expanding the reach of this content within a networked communication environment (Cardoso, 2009). Therefore, in this study, we will consider how the political actors analysed use these three interaction mechanisms allowed by Twitter: retweets, mentions of other Twitter accounts and the inclusion of hyperlinks or web addresses.

4. Interaction Mechanisms

4.1. Retweet

A retweet is an action that allows a user to share, on their own Twitter feed, a tweet originally published by another user, thereby exposing it to their followers and expanding the reach of the original tweet. Retweets are thus a means of redistribution. By retweeting, the user creates or becomes part of a broader “dialogue”, actively participating in the ongoing “conversation”. “Structurally, retweeting is the Twitter-equivalent of email forwarding where users post messages originally posted by others” (Boyd et al., 2010, p. 1).

There are multiple reasons for a user to retweet. Firstly, it can mean support, approval or “endorsement” of a specific piece of content that, for that reason, the user is keen to repost in their feed and thus increase their visibility. However, in political communication, retweeting can also be used to make an ironic point or expose something considered a misjudgement by another user. These situations are usually complemented by a comment or reaction from the retweet’s author explaining their standpoint. Whatever the reason for the retweet, this action always shows interest (typically positive, although it can also be ironic or a complaint) and gives remarkable visibility to the activity of a certain user.

(López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019).

Boyd et al. (2010) have listed several motivations that drive users to retweet: to amplify or spread tweets to new audiences; to entertain or inform a specific audience or as an act of curation; to comment on someone’s tweet by retweeting and adding new content or starting a conversation; to make one’s presence as a listener visible; to publicly agree with someone; to validate others’ thoughts; as an act of friendship, loyalty, or homage; for self-gain, either to gain followers or reciprocity from more visible participants; to save tweets for future personal access. These authors emphasise that retweeting is more than the simple distribution of information. It translates into a more complex social engagement. It is an action taken “to validate and engage with others” (Boyd et al., 2010, p. 1). Thus, “regardless of why users embrace retweeting, through broadcasting messages, they become part of a broader conversation” (p. 10). As part of such conversations, retweeting “contributes to a conversational ecology in which conversations are composed of a public interplay of voices that give rise to an emotional sense of shared conversational context” (Boyd et al., 2010, p. 1).

Previous academic studies examining how political figures use Twitter’s interaction tools have provided insights. Firstly, interactions directly affect content dissemination: each interaction pushes the original content through the network structure in a different way. The added content can reinforce the original message, but it can also change it by criticising it or using irony (Baviera et al., 2019). Meraz and Papacharissi (2013) noted that retweets are often driven by the perceived value of the tweet’s content (rather than, for example, the person who tweeted). Hansen et al. (2011) noted that the determining factors for a message to be retweeted “may depend on the type of content and whether the communication is intended for a broader audience or a more closed community of friends” (p. 6).

A study focusing on Spanish politicians’ activity on Twitter (López-García, 2016) concluded that retweets clearly serve to promote and rebroadcast the political message and shore up the party’s base. Regarding mentions of other users’ accounts, the research highlighted differences between party leaders: some interact with a significant number of accounts, whose owners, moreover, start the interaction by asking questions or, occasionally, criticising certain measures or proposals of their party; other party leaders use mentions to thank other candidates for their work or to respond to mentions made by official accounts (López-García, 2016).

4.2. Mention (@)

The mention (username preceded by the “@” character) allows a direct reference to another user, integrating them into the message, drawing attention to or prompting interaction with the user mentioned. On the other hand, anyone who reads the tweet can link directly to the name mentioned. The fact that different mentions (@1, @2, @3, etc.) can be included in the same tweet makes it the most appropriate, direct and complete interaction tool available on Twitter (López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019). The mention can be used as a mechanism for informally initiating a digital conversation with known or unknown users, thus becoming a public invitation to digital dialogue with enormous strategic utility for political journalists (López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019).

4.3. Weblink

Twitter allows users to add a link to another web address in a post involving any type of content. It is a mechanism to surpass the traditional space limitation of this network by linking to more complete content (textual and audiovisual). In this manner, users lead their followers to additional information that can be developments on the topic covered in the tweet, proof of verification of the thesis being put forward or important references that validate the opinion expressed in the original tweet. The interaction capacity of links is also limited, but especially linked to other mechanisms, such as retweeting or mention (@), it offers the possibility of indirectly approaching content produced by media, parties or political actors (López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019). Political actors have often used this mechanism to add references to media content where they or their party are quoted to their Twitter feed, in a convergence process between new and traditional media.

5. Method, Research Questions and Research Hypotheses

We focused our analysis on the tweets published by party leaders: António Costa, Prime Minister - @antoniocostapm - during the regular periods, local elections and debate on the state budget, and secretary-general of the Partido Socialista (PS; Socialist Party), - @antoniocostaps - during the parliamentary elections pre-campaign and campaign period; Rui Rio, president of the PSD - @ruiriopsd; Catarina Martins, coordinator of the Bloco de Esquerda (BE; Left Bloc) - @catarian_mart; and André Ventura, president of Chega - @andrecventura. This choice enables the coverage of the Twitter presence of the leaders of the prominent parties in Portuguese politics - PS and PSD - as well as the leaders of new parties on the left (BE) and the right (Chega) wings.

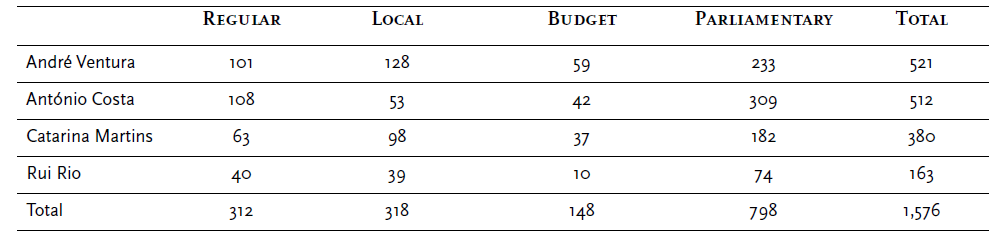

The tweets were collected from a longitudinal perspective, spanning five different periods: the regular period - May 15 to June 15, 2021 (a period with no significant political events); the local elections period - September 1 to 28, 2021; the state budget debate period - October 11 to 28, 2021; the parliamentary pre-campaign and campaign period - December 8, 2021, to January 31, 2022. The number of tweets posted by each party leader over the four periods is shown in Table 1.

This collection formed our database, from which we conducted a content analysis (Bryman, 2012) of the tweets, using the MAXQDA program and producing the outputs in a spreadsheet.

5.1. Research Questions

The research queries (RQ) for which we seek answers are as follows:

RQ 1. To what extent do party leaders establish connections on Twitter, and what is their typology - retweets, mentions of other users’ accounts, and inclusion of web addresses?

RQ 2. When these connections are established, who is the object of these connections - party affiliates, other political parties, the media, or the citizens?

RQ 3. To what extent do party leaders use a media hybridisation approach in their communication strategy on Twitter, incorporating content from traditional media into their posts?

RQ 4. In cases where the hybridisation strategy is used, what forms does it take?

5.2. Research Hypotheses

Our hypotheses are outlined as follows:

Hypothesis 1. Party leaders interact on Twitter, using the medium’s various possibilities - retweets, account mentions, and hyperlink incorporation.

Hypothesis 2. Party leaders’ primary interactions are within their party circle and with the traditional media.

Hypothesis 3. Party leaders use a hybridisation strategy, and the leaders of recently established parties do so more frequently than the leaders of longer-standing parties.

Hypothesis 4. Party leaders use the hybridisation strategy on Twitter to signal their presence in the traditional media, disseminate excerpts from these contributions or react to content published in the traditional media.

6. Discussion of Findings

6.1. Connections

Connecting on Twitter is a communication strategy with two important functions. On the one hand, it guides followers to content created by others they consider relevant.

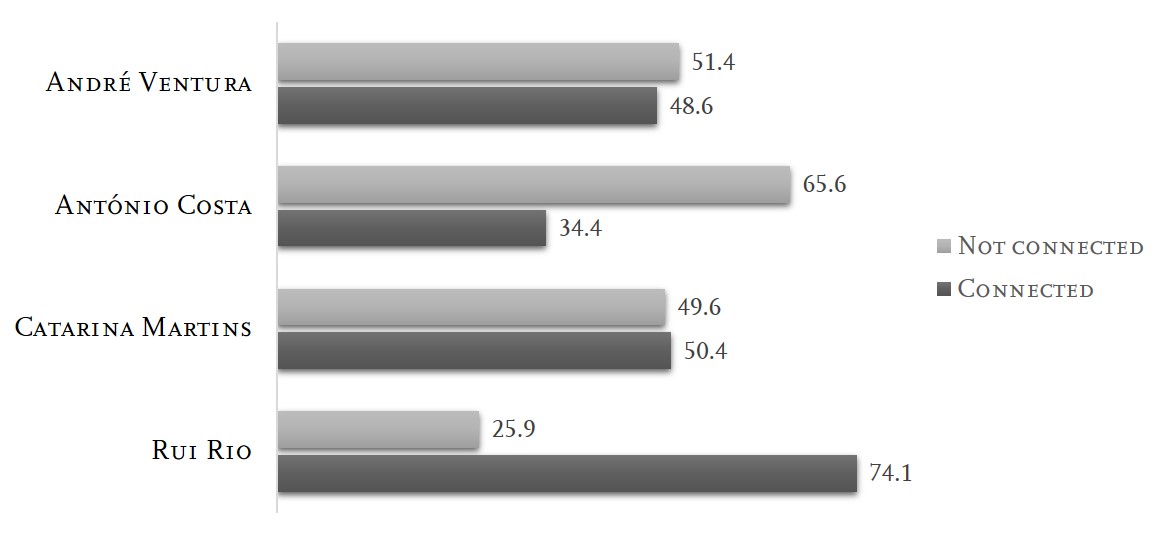

On the other hand, it meets the need for posting and feeds content into their own Twitter feed. In this analysis, the first distinction shows how much the resource is used (Figure 2). Thus, we classify a tweet as not connected when it does not include retweets, mentions of another account or a web address, and a tweet is considered connected when it includes at least one of these three link types.

The graphical analysis shows that the main difference is between the strategy of António Costa and Rui Rio. The PS leader has more of his own tweets and fewer links: most posts do not include a connection (65.6%); around 1/3 of his tweets do (34.4%). Thus, about 2/3 of the PS leader’s tweets are his own content with no other network references. Rui Rio is the party leader with the highest percentage of connections (74.1%); the number of tweets with no connections is the lowest of the four leaders analysed (25.9%). André Ventura has just over half of his tweets (51.4%) with no connections to the web, while the remainder include (48.6%). A similar pattern can be found in Catarina Martins’ practice: half have hyperlinks (50.4%), and the other half do not (49.6%).

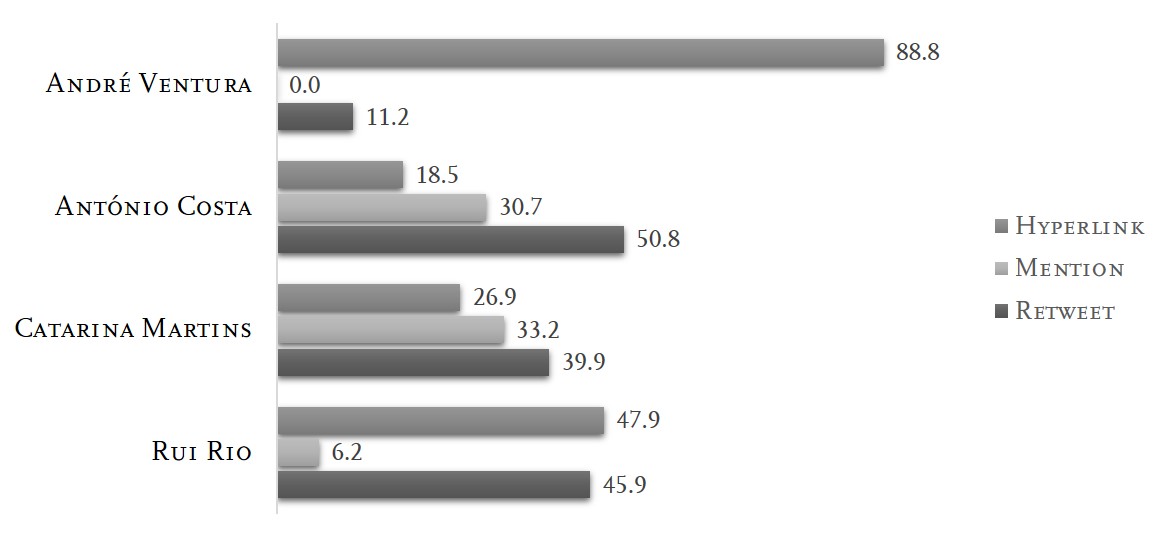

6.2. Types of Interaction

The web’s interaction potential allows political actors to further their communication with other political figures and organisations, citizens, and the media. The data (Figure 3) shows that André Ventura primarily establishes connections through web addresses (88.8%). Only 11.2% are retweets, and no reference to personal accounts. António Costa incorporates retweets (50.8%) in his posts, mentions of other accounts (30.7%) and, to a lesser extent, references to other web addresses (18.5%). Catarina Martins predominantly employs retweets (39.9%), followed by mentions of accounts (33.2%) and, in third place, hyperlinks (26.9%). The main form of connection in Rui Rio’s tweets is the hyperlink (47.9%), then the retweet (45.9%) and, thirdly, the mention of accounts (6.2%).

Thus, we can identify three different communication strategies for using these functionalities. António Costa and Catarina Martins follow a similar strategy, prioritising retweets, followed by mentions and, lastly, web addresses. Rui Rio retweets and hyperlinks almost equally, with fewer mentions to other accounts. Conversely, André Ventura predominantly opts to add web addresses, retweets sparingly and does not use the possibility of mentioning other users’ accounts. These figures show that André Ventura does not use tweets to refer to other protagonists by mentioning their accounts, and the number of retweets is also quite low, primarily related to media publications.

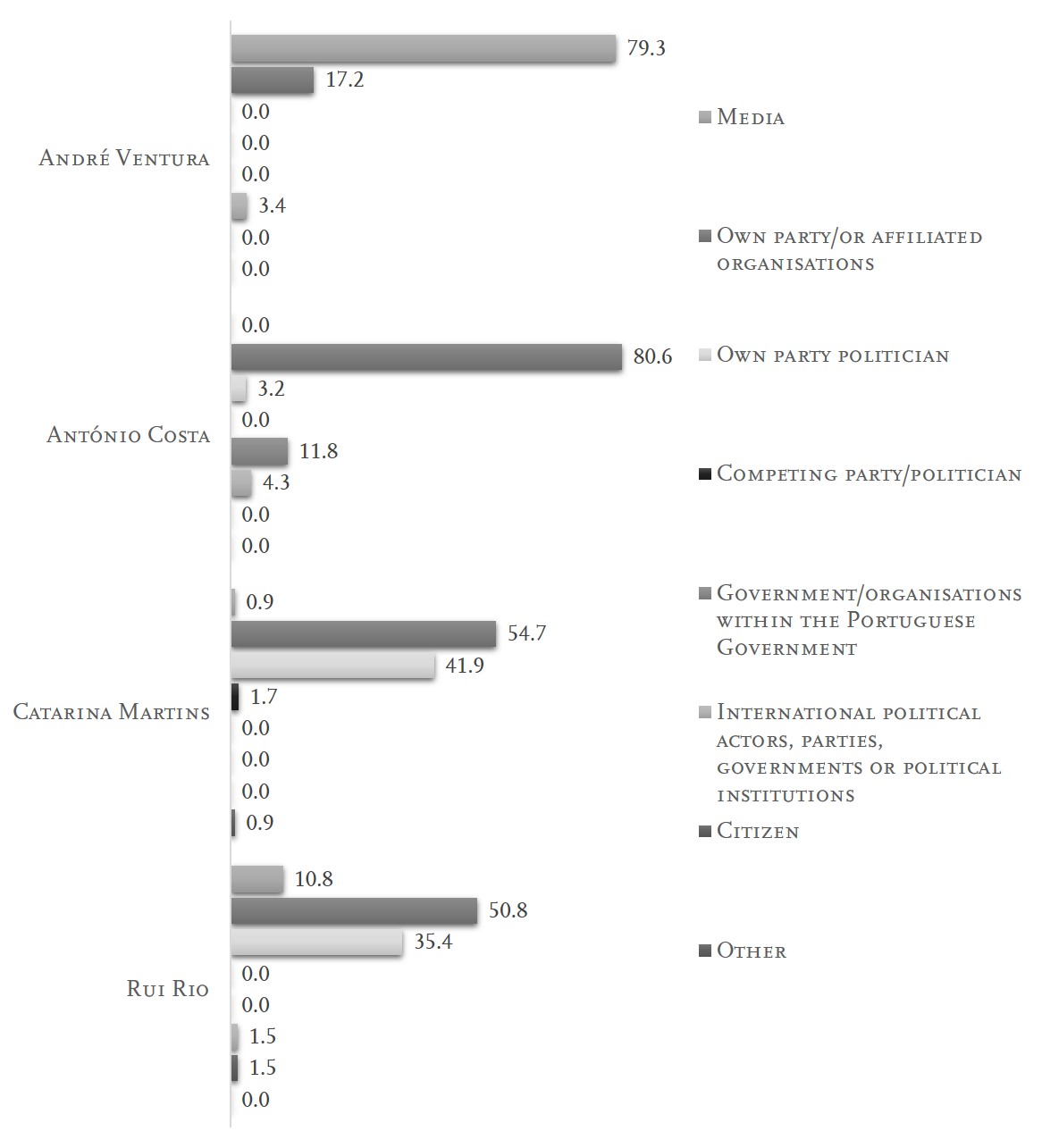

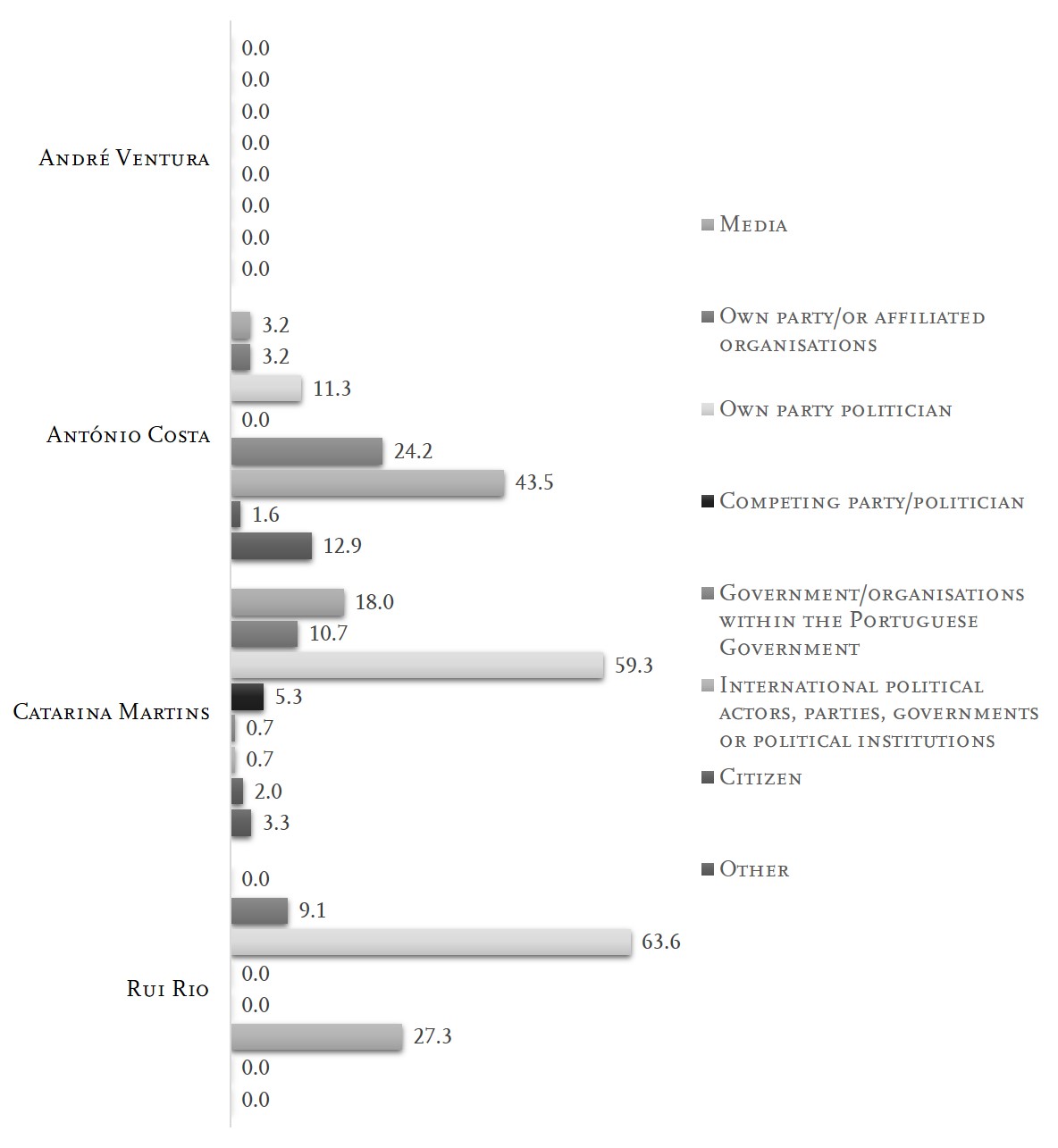

When any of the three types of interaction are incorporated, we have identified three possibilities: links to party circles, the media or citizens. Regarding party circles, there are five hypotheses: the party itself or its internal organisations (party youth wing or parliamentary group, for example); political actors within the party; competing political actors or parties; the Portuguese Government or its internal organisations; international political actors, parties, governments or political institutions.

6.3. Retweet

The four leaders have different retweet practices (Figure 4). António Costa primarily uses retweets to amplify content from his own party’s Twitter feed or internal organisations (80.6%). However, this happens almost exclusively during the parliamentary elections’ pre-campaign and electoral campaign periods. He also retweets content from the Government or Government organisations (11.8%). In third place are the tweets from politicians, parties, governments or international political institutions (4.3%). It should be noted that the PS leader posts a limited number of tweets from political actors within his own party (3.2%). António Costa uses an institutional retweet strategy that refers to tweets produced by organisations or institutions rather than individual political actors. One possible explanation could be that António Costa does not want to signal preferences for individual political actors. For a political actor, a retweet can be interpreted as a preference and thus have a political reading. Firstly, it can be seen as an endorsement or support for a particular piece of content and its author. Perhaps to prevent such interpretations, António Costa retweets a very small number of individual tweets, whether from his ministers, members of his board or party militants, opting instead for retweets from organisations or institutions linked to his political sphere.

André Ventura retweets mostly to disseminate media content (79.3%), often related to himself or his party. Mentions of André Ventura on traditional media’s Twitter accounts are promptly echoed on Ventura’s own Twitter feed, thereby broadening the reach of the original message. Retweets from the party or affiliated organisations come next (17.2%), and in third place are retweets from international political figures, parties, governments, or political institutions (3.4%). Within this latter dimension, we find retweets from leaders of their own European political family, mainly focussing on bilateral contacts.

Catarina Martins retweets almost entirely within her party circle: her party or its affiliated organisations (54.7%) and politicians from her party (41.9%). Thus, Catarina Martins’ Twitter feed replicates tweets from the BE (Figure 5), the parliamentary group, members of Parliament, members of the European Parliament, and BE regional leaders - publications from the various party branches are visible on Catarina Martins’ Twitter feed.

Source. From Temos que reconhecer que há um problema de racismo nas forças policiais em Portugal, avisa @JoanaMortagua [Tweet], by Bloco de Esquerda [@BlocoDeEsquerda], 2021, Twitter. (https://twitter.com/BlocoDeEsquerda/status/1471625514284691461)

Figure 5 Catarina Martins - Bloco de Esquerda retweet

Rui Rio’s retweets are essentially within his party’s circle. Firstly, his party or its affiliated organisations (50.8%) - PSD, Juventude Social Democrata (Social Democratic Youth), parliamentary group and others - and secondly, from politicians within his party (35.4%), particularly those who hold positions in his leadership. Media retweets come in third place (10.8%).

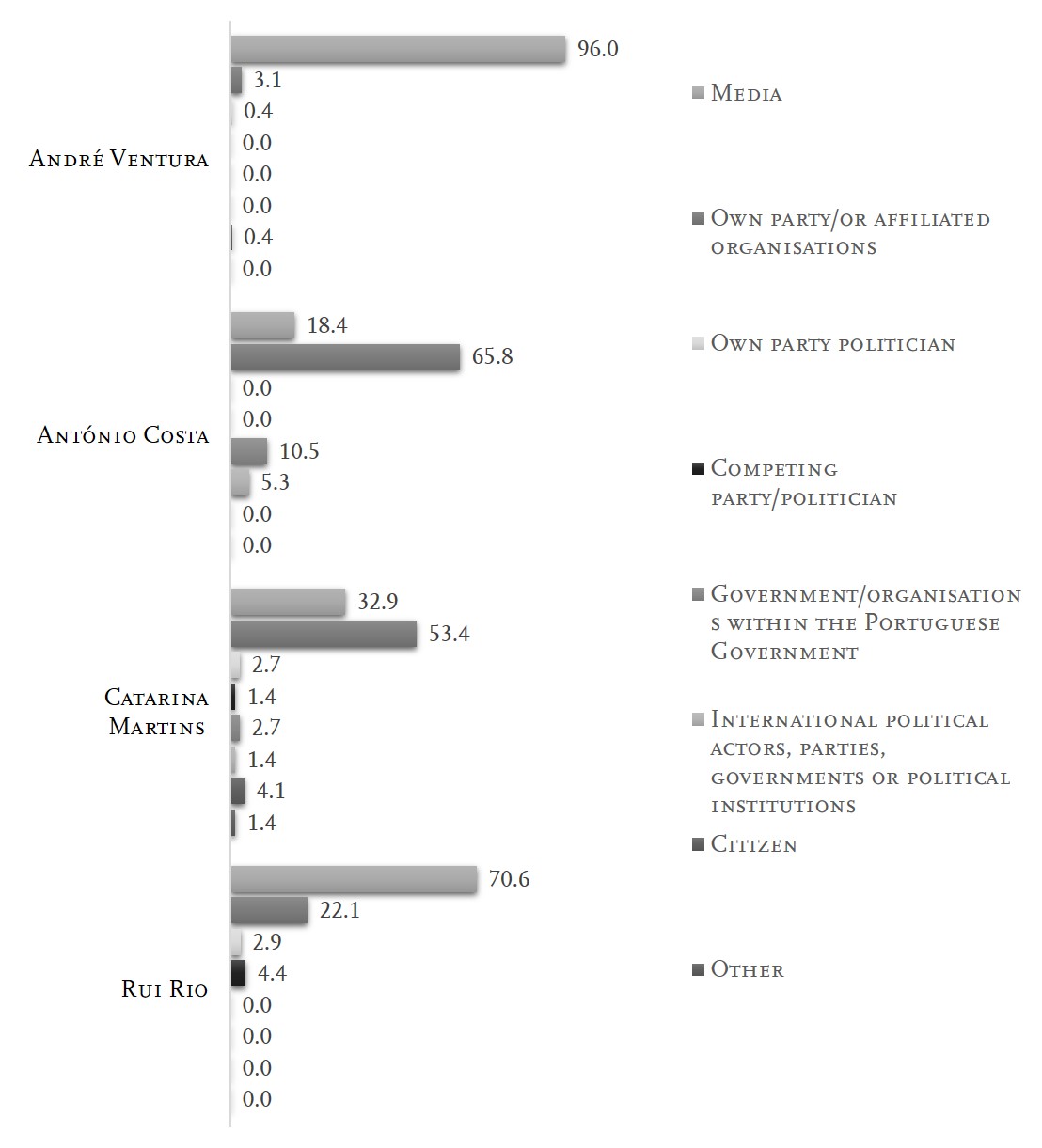

6.4. Mentions of Accounts

The first aspect worth highlighting is that André Ventura’s Twitter account does not make any connections with the accounts of other personalities (Figure 6). On André Ventura’s Twitter account, he is practically the only protagonist. Given that Chega is a highly personalised party whose leader dominates practically all communication by ignoring the names of other party personalities and not making any references to them, it may suggest an effort to reinforce his central role as the party’s public face in the eyes of his followers.

On António Costa’s Twitter account, a notable aspect is that the most frequent mentions are of accounts belonging to international politicians, political parties, governments, or political institutions. A more detailed analysis shows that this primarily stems from his role as Prime Minister. Thus, whenever António Costa engages in meetings with political leaders from other countries, he includes the accounts of the leaders or institutions he connected to on his Twitter feed. For example, at a summit with the President of the Government of Spain, António Costa mentions in his post both Pedro Sánchez’s (the President of the Government) account and the account of the Moncloa (the official residence of the presidency of the Government of Spain). As part of his role as Prime Minister has an international dimension, António Costa expresses this in his tweets. That is a distinguishing mark compared to the other party leaders, who have more limited access to the international political arena. During the election campaign, the PS secretary-general used a similar approach and mentioned the accounts of international leaders from his political family, such as the account of the leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and the German Chancellor with messages of support for the PS campaign (Figure 7). In second place, António Costa’s Twitter account mentions government accounts and Portuguese government institutions (24.2%).

Source. From Obrigado pelo apoio, amigo @OlafScholz! Na Europa, como em Portugal, seguimos juntos no combate por uma sociedade mais justa e progressista [Tweet], by António Costa [@antoniocostaps], 2022, Twitter. (https://twitter.com/antoniocostaps/status/1486291700435849218/)

Figure 7 António Costa’s tweet mentioning Olaf Sholz’s account

In Catarina Martins’ posts, the most mentions are directed towards accounts of BE politicians (59.3%), mainly MPs and leaders, and to the party’s own account (10.7%). The mentions of media accounts (18%) mainly establish a quicker link to Catarina Martins’ interviews or appearances in those media.

Rui Rio predominantly mentions accounts of politicians within his own party (63.6%) and, secondarily, accounts of international politicians, parties, governments, or political institutions (27.3%). In the latter case, he references meetings with international leaders from his political family or within the context of international organisations to which the PSD is affiliated, such as the European People’s Party. In third place, he mentions the party itself or its affiliated organisations (9.1%).

6.5. Connecting on the Web

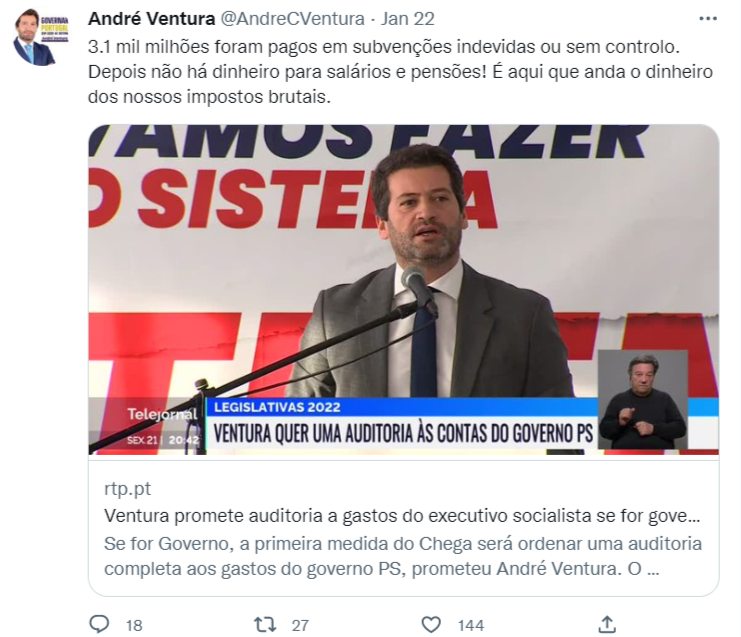

The inclusion of web addresses was noted earlier as the main connection mechanism used by André Ventura on Twitter (Figure 8). This communication strategy aims to establish links with the media outlets, which is the main destination for the hyperlinks (96%). Thus, all references in the media universe involving the name of André Ventura and his party are shared on his Twitter account (Figure 9).

Source. From 3.1 mil milhões foram pagos em subvenções indevidas ou sem controlo. Depois não há dinheiro para salários e pensões! [Tweet], by André Ventura [@AndreCVentura], 2022, Twitter. (https://twitter.com/AndreCVentura/status/1484906476590272517)

Figure 9 Tweet by André Ventura containing a link to media content: television

Rui Rio uses a similar strategy, but to a lesser degree: the main link he establishes is to the media (70.6%), primarily to react to publications in the traditional media, either about general politics or directly involving him. In the second place, he uses web addresses to his own party or party organisations (22.1%). References to competing politicians or parties (4.4%) and politicians from his party (2.9%) follow.

António Costa’s case shows that most links established are with his own party (65.8%). This was particularly evident during the parliamentary election campaign when PS’ tweets were systematically replicated via hyperlinks on the leader’s account. Secondly, but by a significant margin, there were links to the media (18.4%) and, thirdly, the Portuguese Government or Government organisations (10.5%). We also identified links to international politicians, parties, governments or political organisations (5.3%). There were no links to competing politicians or parties, politicians from his own party or citizens. Thus, António Costa’s Twitter strategy tends to remain within the boundaries of his party, emphasising his party through a form of “self-referentiality” (García-Ortega & Zugasti-Azagra, 2018). Catarina Martins’ strategy has some similarities. She establishes links primarily to her own party or party organisations (53.4%), then to the media (32.9%) and thirdly, to citizens (4.1%).

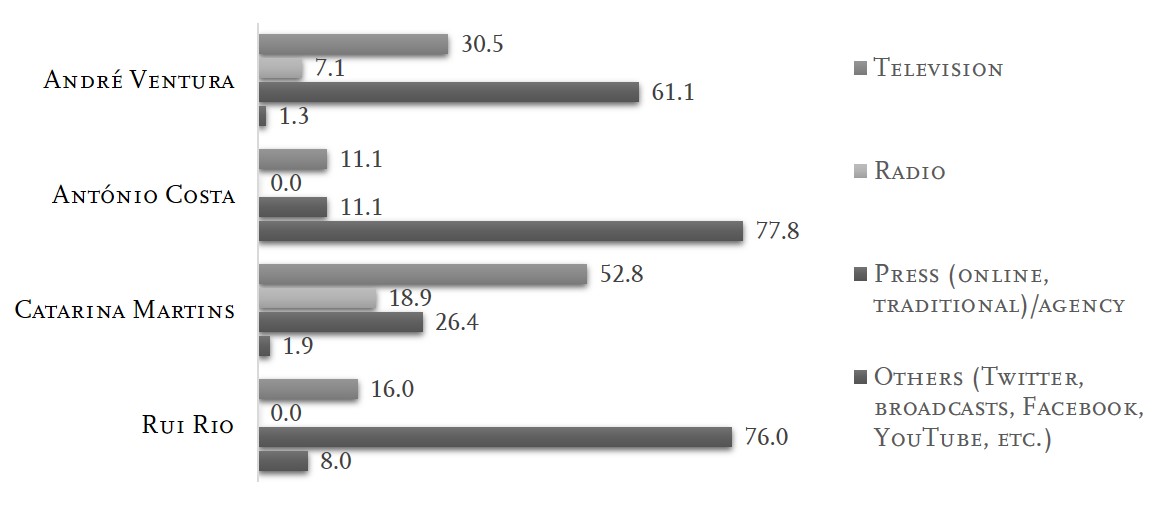

6.6. Hibridisation: Connecting with the Media

Building on the concept of media hybridisation, which highlights the intersections between new media like Twitter and traditional media - television, print, and radio (Chadwick, 2013), we examined this category to determine which traditional media outlets are the focus of interaction by party leaders on Twitter and to what extent (Figure 10).

André Ventura predominantly establishes links with the press (online, traditional, and agencies), accounting for 61.1% of his interactions, primarily relating to news articles about himself. Subsequently, he links to television (30.5%), mainly encompassing interviews and news related to André Ventura, and radio (7.1%).

In António Costa’s Twitter connections, the “other” category takes precedence (77.8%), including connections to networks such as YouTube and Facebook. This clearly sets him apart from the other party leaders: António Costa is the party leader who establishes the most connections with new media and the least with traditional media. The press and television appear in second place with the same value (11.1%).

Catarina Martins’ primary media connection on Twitter is television (52.8%), followed by the press (26.4%) and, in third place, radio (18.9%) - the traditional media.

On Rui Rio’s Twitter account, the press came first (76%), then television (16%) and, lastly, the “other” category (8%).

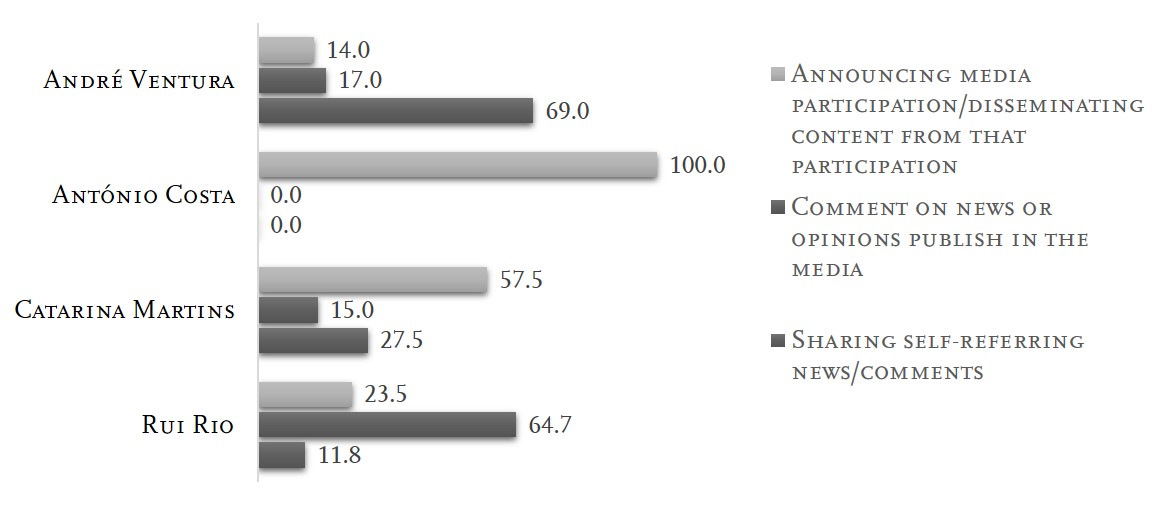

7. Hybridisation: Typology of Media Interactions

This section investigates how party leaders use the Twitter platform to establish connections with traditional media and examines the type of content that leads to this hybridisation.

We consider three dimensions: (a) announcing participation in media shows, such as interviews and debates, or disseminating content that stems from these participations; (b) sharing news or comments about themselves; and (c) commenting on news or opinions published in the media.

Regarding the first dimension, the fact that political leaders can announce on Twitter their participation in traditional media shows or disseminate content resulting from these participations is a strategy that has several advantages. Firstly, it is a means to promote the show itself, making more citizens, in this case Twitter followers, aware of the event and thus facilitating their engagement with the program. Secondly, it allows leaders to select and edit the content they want to disseminate from their participation, essentially taking on the role of gatewatchers (Bruns, 2005). This practice enables political actors to enter a domain traditionally reserved for journalists. However, while journalists follow editorial criteria for content curation, political actors’ criteria are assumed to be driven by political and partisan interests. In other words, political actors can use their Twitter accounts to publish segments of their participation in interviews and debates that align with their communication strategy and political interests.

The second dimension involves the possibility of political actors incorporating news or comments published in the traditional media into their Twitter feeds. This feature allows political leaders to amplify the impact of traditional media publications by making them reach their followers.

Thirdly, on their Twitter account, political actors can comment or react to news or opinions expressed in the traditional media. This practice aligns with the growing phenomenon of media hybridisation. Traditional mass media outlets typically broadcast news and opinions, and it was traditionally the role of journalists to request party leaders’ opinions or responses to this content. On the other hand, should there be such reactions, they could be integrated into the next edition, and there was always a time gap between the news and the possible reaction. Twitter has bridged this gap by allowing party leaders to react immediately if they choose to do so. In this case, they can incorporate the content published in the traditional media and their own comments into their Twitter feed.

We shall now examine how party leaders, the focal point of this study, put these interactions into practice (Figure 11).

In André Ventura’s case, the emphasis in hybridisation is primarily on sharing news or comments (69%), followed by commenting on news or opinions (17%) and announcing media participation or appearances (14%).

António Costa uses only one of the hybridisation features considered here. The PS leader uses Twitter to announce his presence in the media or disseminate edited content from it. He never shares news or comments about himself or on news or opinions in the media.

Catarina Martins uses all three functions to varying degrees. She predominantly uses the possibility of announcing and promoting content from her media participation (57.5%), followed by sharing news or comments (27.5%) and, finally, commenting on news or opinions (15%).

Rui Rio’s strategy has a different approach. Firstly, he comments or reacts to news published in the media (64.7%), often critically or ironically. Secondly, he uses Twitter to promote his participation or content from his participation in media shows (23.5%) and share news from the traditional media (11.8%).

8. Conclusions

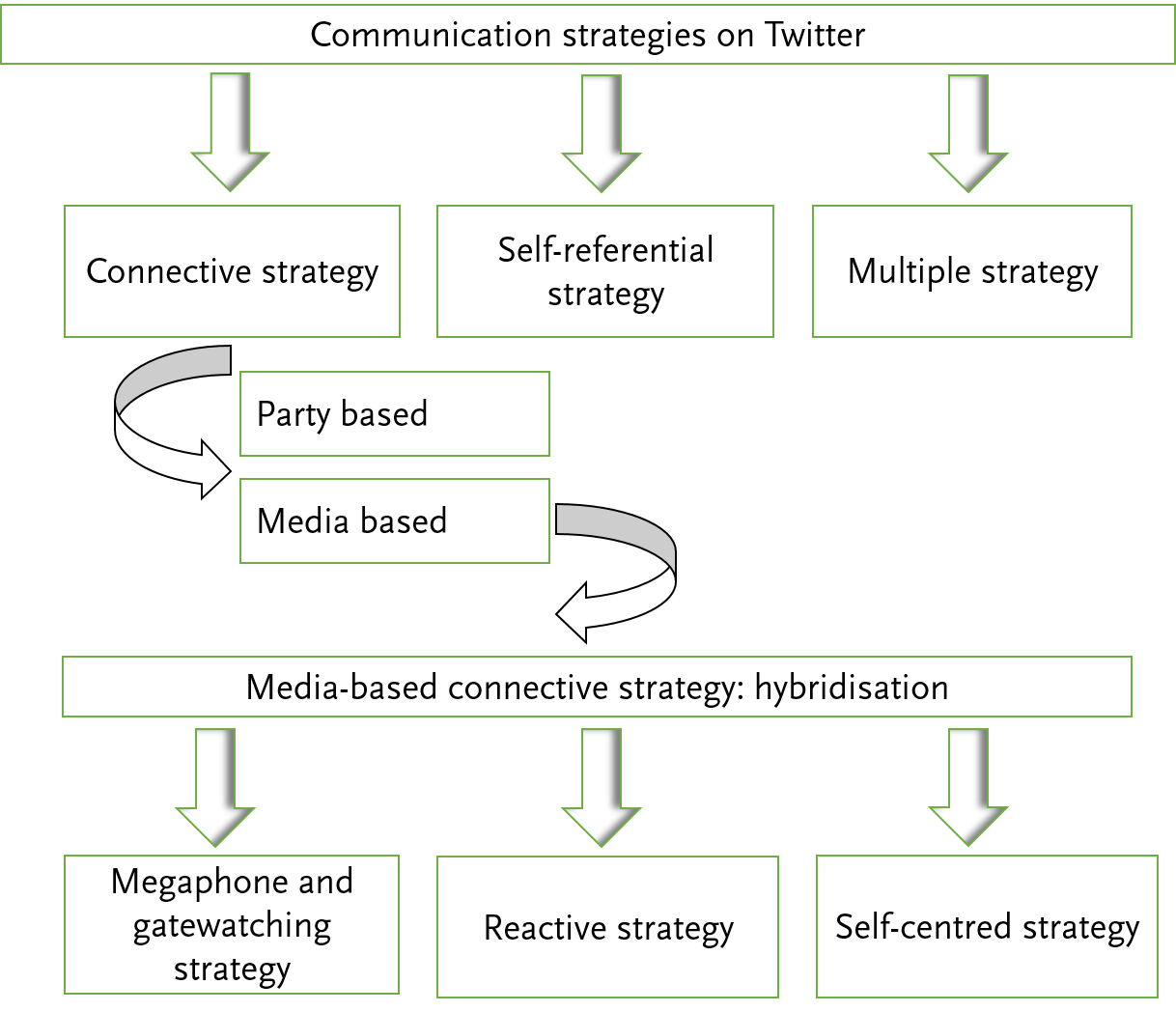

The data collected in this research allows for establishing a typology of communication strategies implemented by party leaders on Twitter, which we illustrate graphically (Figure 12).

As per the definitions, the “connective strategy” pertains to communication that centres around creating interactions with other users, often through mechanisms such as retweets, account mentions or hyperlinks. The “self-referential strategy” involves communication primarily disseminating personal and political content relating to the leaders themselves. The “multiple strategy” encompasses communication that combines original content production and establishing connections with other users.

The four party leaders follow the multiple strategy but with subtle variations. António Costa leans more towards a self-referential approach, predominantly using Twitter to disseminate his own content. In contrast, Rui Rio tends to have a more connective approach, as he actively establishes connections via Twitter, particularly to react to news or opinions on national politics. André Ventura and Catarina Martins strike a more even balance between these two possibilities.

The connective strategy can be party-based - when interactions are primarily established with the structures and members within the party circle - and/or mediabased - when connections are established with other media, namely traditional media, combining content from television, radio, and newspapers on Twitter, as part of a hybridisation process.

Rui Rio and Catarina Martins are the leaders who most exploit party-based connections. The PSD leader favours interactions with his party and his party’s political actors, namely the members of his core group. Catarina Martins employs an “endogamous” approach to Twitter, primarily establishing connections with member of Parliament, members of the European Parliament, leaders and various organisations in her party. In essence, it is a form of communication within the party “bubble”, where her followers gain access to the posts of the BE and its key members. Regarding party-based connections, António Costa and André Ventura follow a similar strategy. The PS leader avoids direct interactions with party members, which could be interpreted as expressions of preference or endorsement, opting instead to emphasise his international contacts in the party connections he establishes. André Ventura also establishes very few connections with his party and party members adopting a strategy that tends to favour political personalisation (Van Aelst et al., 2017), a trend in contemporary political communication characterised by the prominence of individuals and their attributes over political parties and ideologies (Swanson & Mancini, 1996).

The media hybridisation strategy encompasses three possibilities: the “megaphone and gatewatching strategy” - when the content posted on Twitter is used to announce future appearances on television, radio, and newspapers (megaphone) or to promote segments of these appearances that they have edited themselves (gatewatching). The “reactive strategy” - when the content posted on Twitter discloses a reaction (comment, response, context, criticism) to content published by other media, particularly traditional media, “me - about the media”, sometimes assuming an adversarial position. The “self-centred strategy” - when the content posted on Twitter replicates the references to the leader in the traditional media, positioning the party leader at the centre of communication, “me - in the media”.

Portuguese party leaders adopt different hybridisation strategies. António Costa only interacts with the traditional media to announce his participation in shows and disseminate content stemming from these participations - a megaphone and gatewatching strategy - and does not use Twitter to respond, react to or share news and comments. Twitter is thus a platform for displaying his actions rather than debating the ideas surfacing in the media. Catarina Martins follows a similar strategy, using Twitter to announce her participation and share segments of her media presence. Rui Rio predominantly follows a reactive strategy - Twitter is where he comments, reacts or responds to the traditional media, often taking a critical and challenging stance towards the traditional media. The leader of the Chega party heavily relies on media hybridisation, replicating all the references to him in the traditional media on his Twitter account - a self-centred strategy. This practice has three advantages: it suggests to followers that he is a politician with a high profile in the traditional media, highlighting his relevance in the political system; it amplifies the impact of publications in the traditional media by reaching voters who will eventually use the new media to access information; it allows him to add his own comments or explanations to the references made about him, whether favourable or unfavourable. André Ventura’s Twitter account tells the story of André Ventura in the traditional media.

In short, all the party leaders use Twitter’s interactive potential with different intensities. They use Twitter’s interaction methods differently, but mostly in an intra-party context. Twitter stands as a new arena for conversation between actors from the same political-party sphere and a forum for engaging with politicians and traditional media rather than a territory for dialogue with citizens or inter-party communication. It is not possible to determine a pattern of use based on political notions of left/right or older/ newer parties; on the contrary, the place that leaders occupy on the political scene - heading the government/leading opposition parties and the individual profile of each party leader are variables that seem to have a greater influence on communication practice on Twitter. The study confirms party leaders’ commitment to a media hybridisation strategy, reinforcing convergence between platforms and thus redefining the media environment in which political communication takes place, marked by the communication of communication, which is affirmed as “the communication practice that is both the most common and the most distinctive of our contemporary way of communicating” (Cardoso, 2023, p. 287).

REFERENCES

Artwick, C. G. (2013). Reporters on Twitter: Product or service? Digital Journalism, 1(2), 212-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2012.744555 [ Links ]

Baumman, A., Fabian, B., Lessmann, S., & Holzberg, L. (2016, 12-15 de junho). Twitter and the political landscape - A graph analysis of German politicians. 24th European Conference on Information Systems, Istambul, Turquia. [ Links ]

Baviera, T., Calvo, D., & Llorca-Abad, G. (2019). Mediatization in Twitter: An exploratory analysis of the 2015 Spanish general election. The Journal of International Communication, 25(2), 275-300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13216597.2019.1634619 [ Links ]

Blumler, J. G. (2013, 12 de setembro). The fourth age of political communication [Discurso de abertura]. Workshop on Political Communication Online, Berlim, Alemanha. [ Links ]

Boyd, D., Golder, S., & Lotan, G. (2010). Tweet, tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on Twitter. In R. H. Sprague, Jr. (Ed.), 2010 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 1-10). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2010.412 [ Links ]

Bruns, A. (2005). Gatewatching: Collaborative online news production. Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Bruns, A. (2012). How long is a tweet? Mapping dynamic conversation networks on Twitter using Gawk and Gephi. Information, Communication & Society, 15(9), 1323-1351. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.635214 [ Links ]

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2012). Researching news discussion on Twitter: New methodologies. Journalism Studies, 13(5-6), 801-814. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2012.664428 [ Links ]

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Burton, M. J., Miller, W. J., & Shea, D. M. (2015). Campaign craft: The strategies, tactics, and art of political campaign. Praeger. [ Links ]

Calvo, D., & Campos-Domínguez, E. (2016). Participation and topics of discussion of Spaniards in the digital public sphere. Communication & Society, 29(4), 219-234. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.29.4.219-234 [ Links ]

Cammaerts, B. (2012). Protest logics and the mediation opportunity structure. European Journal of Communication, 27(2), 117-134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323112441007 [ Links ]

Cardoso, G. (2009). Da comunicação de massa para a comunicação em rede. In R. Cádima, G. Cardoso, & L. L. Cardoso (Eds.), Média, redes e comunicação (pp. 12-48). Quimera. [ Links ]

Cardoso, G. (2023). A comunicação da comunicação. As pessoas são a mensagem. Mundos Sociais. [ Links ]

Casero-Ripollés, A., Feenstra, R. A., & Tormey, S. (2016). Old and new media logics in an electoral campaign: The case of Podemos and the two-way street mediatization of politics. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(3), 378-397. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216645340 [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2011). Communication power. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Christensen, C. (2013). Wave-riding and hashtag-jumping: Twitter, minority ‘third parties’ and the 2012 US elections. Information, Communication & Society , 16(5), 646-666. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.783609 [ Links ]

Coleman, S., & Blumler, J. G. (2009). The internet and democratic citizenship: Theory, practice and policy. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Conceição, R. (2021, 13 de dezembro). Marcelo censura Rui Rio pelo “azar de Rendeiro”. O exbanqueiro já está no tribunal. Observador. https://observador.pt/newsletters/360/marcelo-censura-rui-rio-pelo-azar-de-rendeiro-o-ex-banqueiro-ja-esta-no-tribunal/ [ Links ]

Dinis, D. (2021, 14 de dezembro). Rio insiste: Quem deteve Rendeiro “foi a polícia sul-africana”. E o diretor da PJ “fez um foguetório para beneficiar o PS”. Expresso. https://expresso.pt/politica/2021-12-14-Rio-insistequem-deteve-Rendeiro-foi-a-policia-sul-africana.-E-o-diretor-da-PJ-fez-um-foguetorio-para-beneficiar-o-PS66f991e0 [ Links ]

Enjolras, B. (2014, 8-9 de janeiro). How politicians use Twitter, and does it matter? The case of Norwegian national politicians [Apresentação de comunicação]. International Conference Democracy as Idea and Practice, Oslo, Noruega. [ Links ]

Gainous, J., & Wagner, K. M. (2014). Tweeting to power: The social media revolution in American politics. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

García-Ortega, C., & Zugasti-Azagra, R. (2018). Gestión de la campaña de las elecciones generales de 2016 en las cuentas de Twitter de los candidatos: Entre la autorreferencialidad y la hibridación mediática. El Profesional de la Información, 27(6), 1215-1224. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.nov.05 [ Links ]

Graham, T., Broersma, M., Hazelhoff, K., & Van ‘t Haar, G. (2013). Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 692-716. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.785581 [ Links ]

Hansen, L. K., Arvidsson, A., Nielsen, F., Colleoni, E., & Etter, M. (2011). Good friends, bad news-affect and virality in Twitter. In J. H. Park, L. Yang, & C. Lee (Eds.), Future information technology (pp. 34-43). Springer. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1101.0510 [ Links ]

Jurgen, P., & Jungherr, A. (2015). The use of Twitter during the 2009 German national election. German Politics, 24(4), 469-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2015.1116522 [ Links ]

Kiousis, S. (2002). Interactivity: A concept explication. New Media & Society, 4(3), 355-383. https://doi.org/10.1177/146144402320564392 [ Links ]

Kreiss, D. (2014). Seizing the moment: The presidential campaigns’ use of Twitter during the 2012 electoral cycle. New Media & Society, 18(8), 1473-1490. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814562445 [ Links ]

Kwak, H., Lee, C., Park, H., & Moon, S. M. (2010). What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web (pp. 591-600). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1772690.1772751 [ Links ]

Lee, E., & Shin, S. Y. (2012). Are they talking to me? Cognitive and affective effects of interactivity in politicians Twitter communication. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour, and Social Networking, 15(10), 515-520. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0228 [ Links ]

Lee, N. Y., Kim, Y., & Kim, J. (2016). Tweeting public affairs or personal affairs? Journalists’ tweets, interactivity, and ideology. Journalism, 17(7), 845-864. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884915585954 [ Links ]

Lewis, S., Holton, A., & Coddington, M. (2014). Reciprocal journalism: A concept of mutual exchange between journalists and audiences. Journalism Practice, 8(2), 229-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.859840 [ Links ]

López-García, G. (2016). ‘New’ vs ‘old’ leaderships: The campaign of Spanish general elections 2015 on Twitter. Communication & Society, 29(3), 149-168. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.29.3.149-168 [ Links ]

López-Meri, A., Marcos-García, S., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2017). What do politicians do on Twitter? Functions and communication strategies in the Spanish electoral campaign of 2016. El Profissional de la Información, 26(5), 795-804. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.02 [ Links ]

López-Rabadán, P., & Mellado, C. (2019). Twitter as a space for interaction in political journalism. Dynamics, consequences and proposal of interactivity scale for social media. Communication & Society, 32(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.32.1.1-18 [ Links ]

Maarek, P. J. (2011). Campaign communication and political marketing. Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

McNair, B. (2017). An introduction to political communication (6.ª ed.). Routledge. [ Links ]

Meraz, S., & Papacharissi, Z. (2013) Networked gatekeeping and networked framing on #Egypt. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(2), 138-166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161212474472 [ Links ]

Moinuddin, S. (2019). The political Twittersphere in India. Springer. [ Links ]

Morris, D. S., & Morris, J. S. (2017). Evolving learning: The changing effect of Internet access on political knowledge and engagement (1998-2012). Sociological Forum, 32(2), 339-358. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12333 [ Links ]

Murthy, D. (2012). Towards a sociological understanding of social media: Theorizing Twitter. Sociology, 46(6), 1059-1073. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511422553 [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2000). A virtuous circle: Political communications in post-industrial societies. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Parmelee, J. H., & Bichard, S. L. (2012). Politics and the Twitter revolution: How tweets influence the relationship between political leaders and the public. Lexington Books. [ Links ]

PCP acusa Rio de querer “dar ordens à PJ” sobre “quem pode ou não” ser detido. (2021, 16 de dezembro). SIC Notícias. https://sicnoticias.pt/pais/2021-12-16-PCP-acusa-Rio-de-querer-dar-ordens-a-PJ-sobre-quem-pode-ou-nao-ser-detido-8240c859 [ Links ]

Pfetsch, B., & Esser, F. (2012). Comparing political communication. In F. Esser & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), Handbook of comparative communication research (pp. 25-47). Routledge. [ Links ]

Rafaeli, S., & Sudweeks, F. (1997). Networked interactivity. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 2(4), Artigo JCMC243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00201.x [ Links ]

Ramos-Serrano, M., Gómez, J. D. F., & Pineda, A. (2016). ‘Follow the closing of the campaign on streaming’: The use of Twitter by Spanish political parties during the 2014 European elections. New Media & Society, 20(1) 122-140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816660730 [ Links ]

RTP Play. (2021, 14 de dezembro). Eleições legislativas 2022 - Entrevistas líderes partidários: PSD - Rui Rio|Ep. 7 [Vídeo]. https://www.rtp.pt/play/p9596/e585997/eleicoes-legislativas-2022-entrevistas-lideres-partidarios [ Links ]

Rui Rio sugere que calendário eleitoral influenciou prisão de Rendeiro. (2021, 12 de dezembro). Rádio Renascença. https://rr.sapo.pt/noticia/pais/2021/12/12/rui-rio-sugere-que-calendario-eleitoral-influenciou-prisao-de-rendeiro/264247/ [ Links ]

Stieglitz, S., & Dang-Xuan, L. (2014). Social media and political communication - A social media analytics framework. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 3(4), 1277-1291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-012-0079-3 [ Links ]

Stromer-Galley, J. (2014). Presidential campaigning in the internet age. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Swanson, D. L., & Mancini, P. (1996). Politics, media, and modern democracy. Praeger. [ Links ]

Van Aelst, P., Sheafer, T., Hubé, N., & Papathanassopoulos, S. (2017). Personalization. In C. de Vreese, F. Esser, & D. N. Hopmann (Eds.), Comparing political journalism (pp. 112-130). Routledge. [ Links ]

Zamora-Medina, R., Sánchez-Cobarro, P. H., & Martínez-Martínez, H. (2017). The importance of the “strategic game” to frame the political discourse in Twitter during 2015 Spanish regional elections. Communication & Society, 30(3), 229-253. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.30.3.229-253 [ Links ]

1This work was produced before the social network’s rebranding from Twitter to X. The manuscript was submitted to the journal in May, and Elon Musk announced the name change in July. Nevertheless, the manuscript was not altered to reflect the change. This decision was based on two factors: the continued recognition of “Twitter” by the general public, particularly non-users, and the substantial effort required to revise other related terminology if the text were to be corrected.

Received: May 13, 2023; Accepted: August 14, 2023

texto en

texto en