Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Lusófona de Estudos Culturais (RLEC)/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies (LJCS)

versão impressa ISSN 2184-0458versão On-line ISSN 2183-0886

RLEC/LJCS vol.10 no.2 Braga dez. 2023 Epub 28-Fev-2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/rlec.4694

Thematic Articles

Multiplicities, Narratives of Life and Collective Memory of Teaching in the Comic Fessora!

iPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Estudos de Linguagens, Departamento de Linguagem e Tecnologias, Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

iiPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Informação, Departamento de Informação, Mediações e Cultura, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

This article features the comic Fessora!, drawn and written by Brazilian author Aline Lemos, published independently and through crowdfunding in 2021. The narrative focuses on the author's personal experience of teaching one semester of history in a public school. Aline presents a set of 15 stories that address their personal memories with co-workers, students, and parents. Six stories in comic format were selected in order to understand, based on the memories and fragments of life narrated, the tensions and confluences between the work experiences highlighted by the artist. They portray their personal experience as a teacher, the emergence of a collective that reveals to us the daily life of public-school teachers in Brazil. In our analysis, we used the perspective of the life narrative of the Argentine linguist Leonor Arfuch (2002/2003, 2013) on the relationship between contemporary life narratives and the biographical space, plus the notion of collective memory (Halbwachs, 1950/1999; Bosi, 2009) to understand the multiplicity of experiences arising from individual memory. The conclusion reached is that Aline Lemos’s work highlights the challenges of education on the valorization of the teacher and the social inequalities in the classroom.

Keywords: life narrative; collective memory; comic book; teaching; education

O artigo apresenta o quadrinho Fessora!, desenhado e escrito pela brasileira Aline Lemos, publicado de modo independente e por financiamento coletivo em 2021. A história narrada tem como enfoque a experiência pessoal da autora quando foi docente de história no ensino público por um semestre. A autora nos apresenta um conjunto de 15 histórias que abordam suas memórias pessoais com colegas de trabalho, corpo discente e pais. Neste texto, foram selecionadas seis bandas desenhadas, a fim de compreender, a partir das memórias e dos fragmentos de vida narrados, as tensões e confluências entre as vivências de trabalho acionadas pela artista. Retratam sua experiência pessoal como professora, revelando o cotidiano de professores da educação pública no Brasil. Para esta análise, usamos a ótica da narrativa de vida da linguista argentina Leonor Arfuch (2002/2003, 2013), quanto à relação entre narrativas de vida contemporâneas e o espaço biográfico; e a noção de memória coletiva (Halbwachs, 1950/1999; Bosi, 2009) para compreender a multiplicidade de experiências a partir da memória individual. Conclui-se que Aline Lemos apresenta uma obra que evidencia os desafios da educação sobre a valorização do docente e as desigualdades sociais em sala de aula.

Palavras-chave: narrativa de vida; memória coletiva; história em quadrinho; docência; educação

1. Introduction

Fessora! is a comic book written and illustrated by Aline Lemos1. Published independently in 2021, it received financial aid from crowdfunding and the Aldir Blanc Cultural Emergency Act, of the Belo Horizonte City Hall. In their graphic narrative, Lemos portrays their experiences as a public-school teacher in Minas Gerais during the semester they held the position of history teacher2. This life experience was marked by challenges arousing more questions than answers, as the artist points out in the book.

We have taken comic books based on what Postema (2018) postulates as art and narrative forms, a system in which fragmented and distinct elements act together to create a whole that is complete. The comics, therefore, have pictorial and textual parts, often presenting a mix of the two. We also rely on Paulo Ramos (2011, 2014) to understand this art form and narrative as a hypergenre that functions as a kind of “label” within which several common genres come together, although they are individual and autonomous, since they are composed and named in different ways. In that author’s understanding, this is because these autonomous genres are shaped in interactive and sociocognitive processes and, therefore, do not happen automatically.

This hypergenre of comics is made up of various cartoon formats (Ramos, 2011, p. 105), such as caricatures (charges3), cartoons, comic strips, serial comic strips, free strips, digital comics, graphic novels, and many others. For the purposes of our research object, we are specifically interested in autobiographical comics, in other words, the author’s own narratives and drawings.

Associating autobiographical and/or self-referential comics with writing about oneself and rhetoric, researcher Nataly Costa Fernandes Alves (2021) states that character drawings often allude to the social, physical, and sexual characteristics of their creators. She calls this practice by the name “drawings of the self”, in which protagonists are drawn with features similar to those of the artists who conceive them in physiological, social and everyday aspects. These also contain what the researcher calls “visual parrhesia” (Alves, 2021, p. 59)4. As the researcher explains, in parrhesia the speaker talks candidly and says what he thinks without making the truth palatable for the comfort of the readers or listeners, disregarding the risks of their violent reactions and rejection. For Alves (2021), artists use everyday life as the basis on which they present the experiences of their characters in the drawings of themselves, and it is here that the similarities between comic artists and their protagonists can be perceived. Considering the ideas explored so far, we understand Fessora! as being a drawing of the self, as well as a narrative of the self.

Reflecting on the act of narrating oneself, to which we add the drawing of oneself, the Argentine linguist Leonor Arfuch (2002/2003) argues that those who narrate a life do not account for it in its entirety. She therefore believes that what matters is not so much the “truth” of the facts, but the way in which the narratives are constructed, the ways in which the accounts are named, and the back-and-forth promoted by the narration, in addition to the point of view and the choices between which fragments of life will be told. This is because it is through this back-and-forth that the recall and memories of a past are activated to speak about today, to give meaning to what is being said. In other words, this movement, this path of narration, gives the narrative of oneself a selfreflexive quality, as the person chooses which story or stories to tell of themselves or of another, making it meaningful (Arfuch, 2002/2003).

Consequently, when we look at testimonial forms and accounts of oneself, as is the case of Fessora!, what matters are the strategies of self-representation and the narrative construction: “it will be, in addition, the truth, the narrative capacity to ‘make believe’, the evidence that the discourse can offer, never outside of its strategies of verifiability, its enunciative and rhetorical marks” (Arfuch, 2002/2003, p. 73). Life narratives, the linguist argues, are not free of fictional aspects. Although they are perceived in their different uses, the persistence of primary genres and the credibility effects triggered come into play through the same rhetorical procedures found in the constitution of the genres of fiction, especially the novel (Arfuch, 2002/2003, p. 73). In this sense, we understand that testimonials, self-reports, life narratives, self-narratives, and drawings of oneself are part of the biographical space.

2. Fessora! in the Contemporary Biographical Space

For Arfuch (2013), the biographical space is a multiplicity of (auto)biographical narrative forms that encompasses canonical genres, such as biography, autobiography, letters, confessions, memoirs, intimate diaries, and correspondence; and contemporary genres such as those that emerge from digital technologies and the internet, to which she adds among other forms of materiality: emails, audiovisual art installations, images and media interviews, talk and reality shows.

This characteristic multiplicity of the biographical space, although diverse, has a common trait: each form tells, in its own way, a story or life experience, according to Arfuch (2002/2003). The researcher argues that there is no “one life” that can be thought of as a one-way street prior to narration. Life, as a form of recounting, is a result contingent on narration in her view. We therefore narrate our experiences in an attempt to make sense of them. Thus, stories of oneself are always inconclusive, a retelling from the beginning, and they privilege experience (Arfuch, 2002/2003). And as we are always going through new experiences, these have a direct bearing on life “as a whole” to the degree they extend “beyond themselves” (Arfuch, 2002/2003, p. 82).

It is this characteristic of the experiences of summoning a totality in an instant and at the same time being the minimum unit of an experience that goes beyond itself when it is directed, in the narration, to life in general - giving light to, rescuing and clipping out experiences - which Arfuch (2002/2003) believes to make the narrative of life one of the most valued signifiers of the biographical space in contemporary culture. This is because the narrative of life appears “impregnated with connotations of immediacy, of freedom, of connection with the ‘being’, with the truth of ‘oneself’, it also attests to the depth of self and offers a guarantee of the very person” (Arfuch, 2002/2003, p. 82). In other words, when narrating a life, ours or others’, the Argentine linguist understands that it is “pinched” from a segment of life to the degree it refers to its whole and beyond the life itself. “This beyond itself of each particular life is perhaps what resonates, as existential restlessness, in autobiographical narratives” (Arfuch, 2002/2003, p. 39).

In this sense, narrating in the contemporary biographical space is to construct oneself from fragments of life. It is articulating traits such as the “moment” and the “totality” towards new questions and more diverse interpretations regarding the narratives of the self (Arfuch, 2002/2003). It is what the author understands as the search for identity and identification in which Aline asks about the path that guides the “I” to the “we”, while revealing a “we” in the “I”, not as a sum of individualities, nor even a grouping of biographical accidents, but homogeneous articulations of shared values in the “(eternal) imagination of life as fullness and fulfillment” (Arfuch, 2002/2003, p. 82).

In this paper, therefore, we consider the comic in question to be part of the biographical space that Leonor Arfuch highlights (2002/2003, 2013). This is because it is an autobiographical narrative comic, that is, the artist “pinches out” and chooses experiences as a teacher in the public school system to build the graphic narrative and give meaning both to this moment in their life and their existential restlessness, as well as to the whole that makes up the individual, Aline Lemos. And by talking about themselves as they draw themselves, Lemos (2021) extrapolates the whole of their life, revealing experiences beyond themselves that also describe the collectivities of teachers and students of public schools in Brazil.

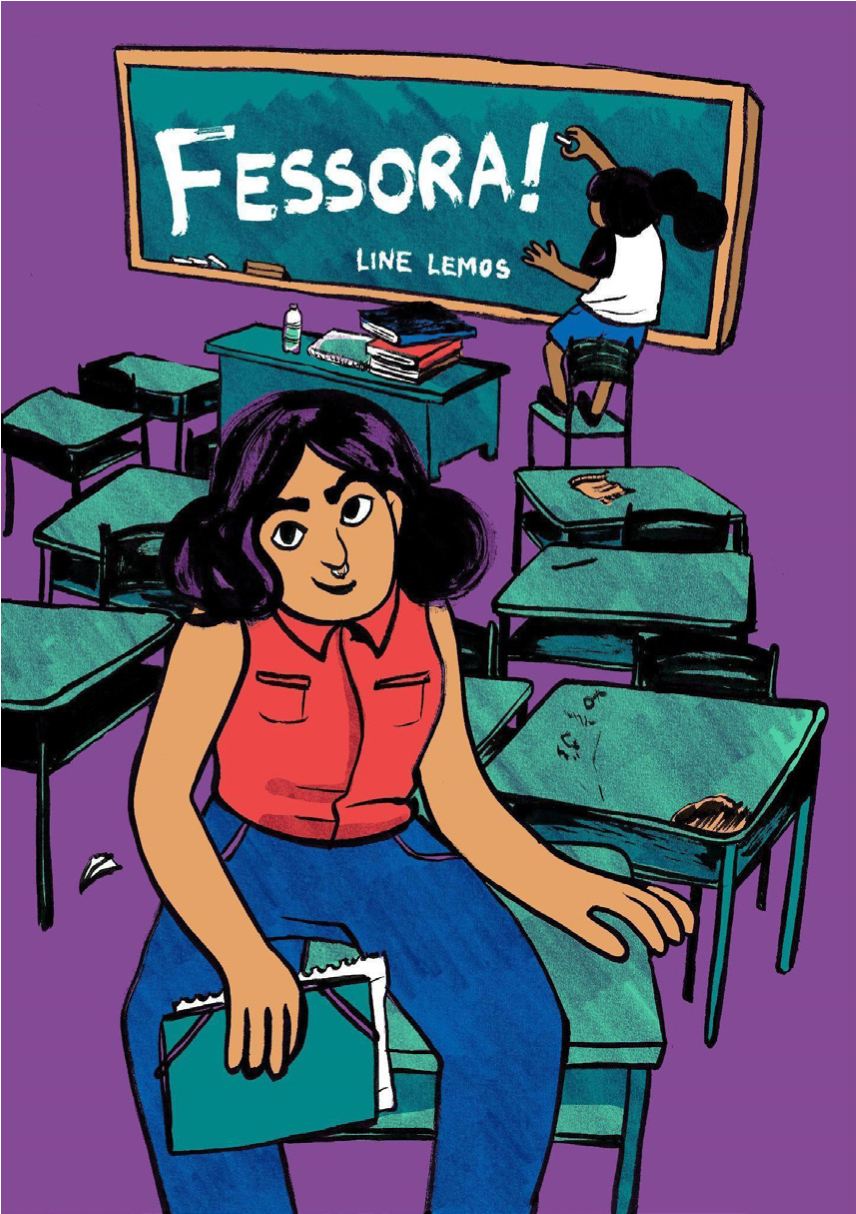

Based on the words of Aline Lemos in the synopsis of the book, where they say that they narrate their “failures, glories and emotions as a novice high school teacher”, we seek to analyze the comic book story Fessora! (Figure 1) from the perspective of Arfuch’s life narrative (2002/2003, 2013), regarding the relationship between contemporary life narratives and the biographical space. Thus, we intend to underscore in the memories and in the fragments of life narrated, the tensions and confluences between the work experiences that the artist chooses to talk about in relation to their personal experience as a teacher, the emergence of a collective, alongside the description of the life of publicschool teachers in Brazil.

Source. From Fessora!, by A. Lemos, 2021. Copyright 2021 by Aline Lemos. (https://alinelemos.company.site/Livro-Fessora-p407250337)

Figura 1 Comic book cover Fessora!

To this end, we start from fragments of the experiences narrated in Fessora!, in which the artist, to some extent, is dealing with issues of an I, but exposes a we, to outline narratives of the experiences of teachers as a collective, which Aline reinforces with statistical and research data on the subject addressed. We divide these narrative paths into moments when Aline deals with: (a) the students; (b) co-workers; (c) themselves; and (d) the students’ relatives, in other words, the school community. We emphasize that these axes do not appear in isolation in the comic book. These are experiences that are interdependent and interconnected with each other.

In regard to the structure of Fessora!, the book contains 15 short stories, divided into chapters interconnected in a larger context, Aline’s experience as a teacher, which can be read together within the author’s narrative logic, or separately without compromising the understanding of each story. In addition, there are two interviews and a dedication, all of which are illustrated. It is through this structure that the comic artist portrays in a sincere and entertaining way the daily life of a teacher in their first experience in the classroom. Exhaustion, frustrations, violence, racism, sexuality, interactions with students and other teachers, difficulty in dealing with time and in demonstrating authority are some of the topics addressed by Aline, who divides their comic book into the following stories: “O Início” (The Beginning); “O Visto” (The Check Mark); “Kathlen” (Kathlen); “Semana” (Week); “Comportamento” (Behaviour); “Estratégias” (Strategies); “O Grito” (The Scream); “Licença” (Leave of Absence); “Tempestade” (Storm); “Ocupado” (Busy); “Turma Ruim” (Bad Class); “Besouro” (Beetle); “Sovaco Cabeludo” (Hairy Armpit); “Violência” (Violence); and “Despedida” (Farewell). All of these words are directly linked to the experiences narrated in each chapter.

Without following a pattern of frame numbers by story, Aline writes Fessora! abusing graphic experimentalism. Not by chance, the book begins and ends with lined pages, like those in a notebook, in which the artist writes the “summary” and the “roll call”, respectively. In the latter, they show the “group of supporters” of the work, that is the names of readers who helped fund the comic book, which was published with crowdfunding, and they leave a check mark there. A clear reference to the work of teachers in the classroom. This practice is also present in one of the chapters of the work.

In addition, the chapters do not follow a closed structure of numbers of frames and their formats, which are explored by the author according to the needs of the story being told. The classrooms and the teachers serve as the main scenario, but other school spaces are also portrayed. The drawings follow the characteristic particularities of Aline, who uses and abuses the simple cartoon-style strokes, for the most part drawn freehand with lines and frames that do not follow a standard geometric structure. All these particularities are also present in their other comic books, such as Lado Bê, a publication which, like Fessora!, uses shades of black and white.

3. When the Illness Is Collective: I Teacher - We Teachers

Thinking about the unicity and multiplicity of the I and the we of the biographical space, Arfuch (2002/2003) says that these are extremely important for outlining the boundaries of public and private space, individual and social space. In the author’s opinion, every account of experience, narrative of oneself or biography is, to some extent, collective. This is because it also deals with issues regarding a period, a group, a generation, and a class that have a common identity narrative. In Fessora!, we believe this is linked to the identity performance of “teachers”, although at a certain point in the narrative Aline claims not to be “a real teacher”: “it did not seem fair to my colleagues to call myself a ‘teacher’” (p. 12). Aline reflects on the sequence of events that lead them to applying to the vacancy four years earlier. Regardless of whether Aline accepted the job out of financial need or the desire to be a teacher, it only took one semester in middle school - 6th to 9th grade (11 to 15 years old) - to experience and share some of the challenges of teaching in a public school in Brazil.

We note what Ecléa Bosi (2009) emphasizes about the collective memory that “entertains the memory of its members, which adds, unifies, differentiates, corrects and erases” (p. 332). The comic is not content to merely relate individual experiences, but it presents us with and reinforces the memories of the category of work and classroom teaching. Aline’s personal stories create points of contact with a collective memory (Halbwachs, 1950/1999). “It is this collective quality, as a mark imprinted on the singularity, that makes life stories relevant” (Arfuch, 2002/2003, p. 100). The researcher stresses that this happens in life narratives published in traditional literary genres, in the media, in the social sciences and in the contemporary biographical space, within which we can include Fessora!. This feeling is also a collective maxim.

The point of contact between collective memory, teachers and experiences in the classroom is therefore traced from the first page of the comic book when “The Beginning” of their trajectory as a teacher is portrayed and the narrative makes the anxiety of the “fessora” aesthetically clear, when she is drawn with sunken eyes, dark circles and an open mouth in a facial expression that reveals their anxiety caused by all of the advice, such as “don’t be so sweet!”, “be careful!”; and verbally expressed by Aline in the frame that closes the page, as the character walks towards the classroom: “I think I’m going to be sick” (p. 7).

The narrative continues, taking this comic further as a great narrative of life in which school experiences are narrated in order to compose the daily life of a publicschool teacher in Brazil, we sense that the climax to Aline’s exhaustion is presented in “O Grito”. Not knowing what to do to contain the class playing and running around inside the room in a chaotic atmosphere, and desperately seeking to silent the students, the teacher yells “shut u-u-u-u-p!” (“cala a bocaaa”; Figure 2). It is the narrative sequence of this scream, in the comic book, that takes them to the doctor’s office, making the final “AAA” of the scream (“…bocAAA”) become the “AAA” of the medical exam in the story “Licença” (Figure 3). After this transition, the doctor tells them, “I’ll give you a week of medical leave, rest your voice and stay away from chalk!” (p. 34), thus revealing the factors that made the teacher sick: the repetitive use of their voice and the long exposure to chalk.

Source. Adapted from “O Grito” and “Licença”, by A. Lemos, 2021, in A. Lemos, Fessora!, pp. 32-33. Copyright 2021 by Aline Lemos.

Figura 2 Collage “O Grito” and “Licença”

Source. From “Licença”, by A. Lemos, 2021, in A. Lemos, Fessora!, p. 34. Copyright 2021 by Aline Lemos.

Figure 3 Comic story “Licença”

The vocal health of teachers of basic education in Brazil is one of the main causes of teacher absence (Reimberg et al., 2022). The publication of the Ministry of Health’s Work-Related Voice Disorder (DVRT) protocol raised awareness of the problem (2018). It states that there is “more vocal illness among teachers than in the general population” (Ministry of Health, 2018, p. 13). This validation as an occupational disease is related to the debate on the mental health of these workers.

By talking about an I, the artist therefore narrates experiences of a collective: the exhaustion of teachers in the country. This is even more evident when Aline uses more than their personal experience as a narrative resource, presenting data from a research paper on illness among basic education teachers in Brazil. As revealed by a survey conducted by Gestrado/UFMG in 2013, most teachers in the country take on duties in more than one school, in addition to combining their teaching duties with other activities to supplement income (Oliveira & Vieira, 2013). Furthermore, in the reality of the school environment, teachers end up playing various roles and social functions in their daily lives, which go beyond teaching the content assigned to them (Carlotto, 2010). According to the author, this is because they are faced with diverse and emerging conflicts in the space and dynamics of relationships with the school community.

These issues are also presented by Aline, who portrays the direct teacher-student, teacher-teacher, and teacher-guardian relationships, both in the classroom and in other school settings. In one of these moments, we meet Antonio, the geography teacher, who reports: “I was away for six months,” and points to the need for self-preservation “before I reached my limit” (p. 35). At the end of this narrative, we discover that, although he’s back at school, Antonio now does administrative work, implying that he is not fully recovered.

Associating words such as “anxiety”, “depression”, “professional exhaustion” - all of which are linked to the illness of teachers - to the research “The Illness of the Teacher in Basic Education in Brazil” (Figure 3), the artist uses their experience as a narrative resource to talk about teachers as a category. This becomes clear when, from the data collected by Nascimento and Seixas (2020), it is revealed that the physical and mental health of this professional class directly influences the precariousness of the work of teachers in Brazil, and the quality of teaching. In other words, the causes of the illness of teachers are mainly issues related to working conditions. These data, therefore, are used by the artist as a narrative resource of proof, since they appear in a way that explains the shared, collective experience of the conditions to which educators are subjected in the country.

Nascimento and Seixas (2020) underline that all these factors combined with high workload and low pay, without the support and social recognition necessary for carrying out this job are conducive to mental and physical illness. Therefore, by making teachers responsible for educating children and teenagers without acknowledging the influence their working conditions have on their mental health, society, school and State contribute to this illness, as defended by Nascimento and Seixas (2020). Work overload and poor working conditions are also highlighted by Oliveira and Vieira (2013) as complaints of teachers. The research points out that teachers report having to take home work-related tasks and complain about the classroom environment, e.g. noise, poor ventilation and lighting. In addition to these problems, the psychosocial risks of the profession are associated with issues such as ergonomic, vocal and postural demands; the number of classes taught; and poor relationships with students, which can cause injuries due to repetitive symptoms (Santos et al., 2012). Among the problems related to the teachers’ work and health, therefore, we highlight factors that cause malaise such as stress, burnout syndrome, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and other chronic diseases that, when associated, can lead to aggravated conditions such as heart and circulatory diseases (Santos et al., 2012).

When portraying daily school life, it is not by chance that the representation of exhaustion is a recurring feature in the comic book, whether as a central theme or as an element of another situation portrayed. In the story “Semana”, it appears when Aline is drawn first as thoughtful, then later presents gradual changes in their features until, finally, they are in the story wrapped in a cloud and with clear traces of exhaustion, such as dark circles and sunken eyes. These traits also accompany the story “Comportamento”. We should point out that the two stories are told before “O Grito” and “Licença” , thus giving Aline’s exhaustion a linear trajectory shown on each page of the comic strip until, finally, their body reaches its limit (Figure 4).

Source. Adapted from “Comportamento”, by A. Lemos, 2021, in A. Lemos, Fessora!, pp. 19, 21-22. Copyright 2021 by Aline Lemos.

Figure 4 Collage traces of exhaustion in Aline

4. When the Body Is Not “Neutral”: The Political Memory

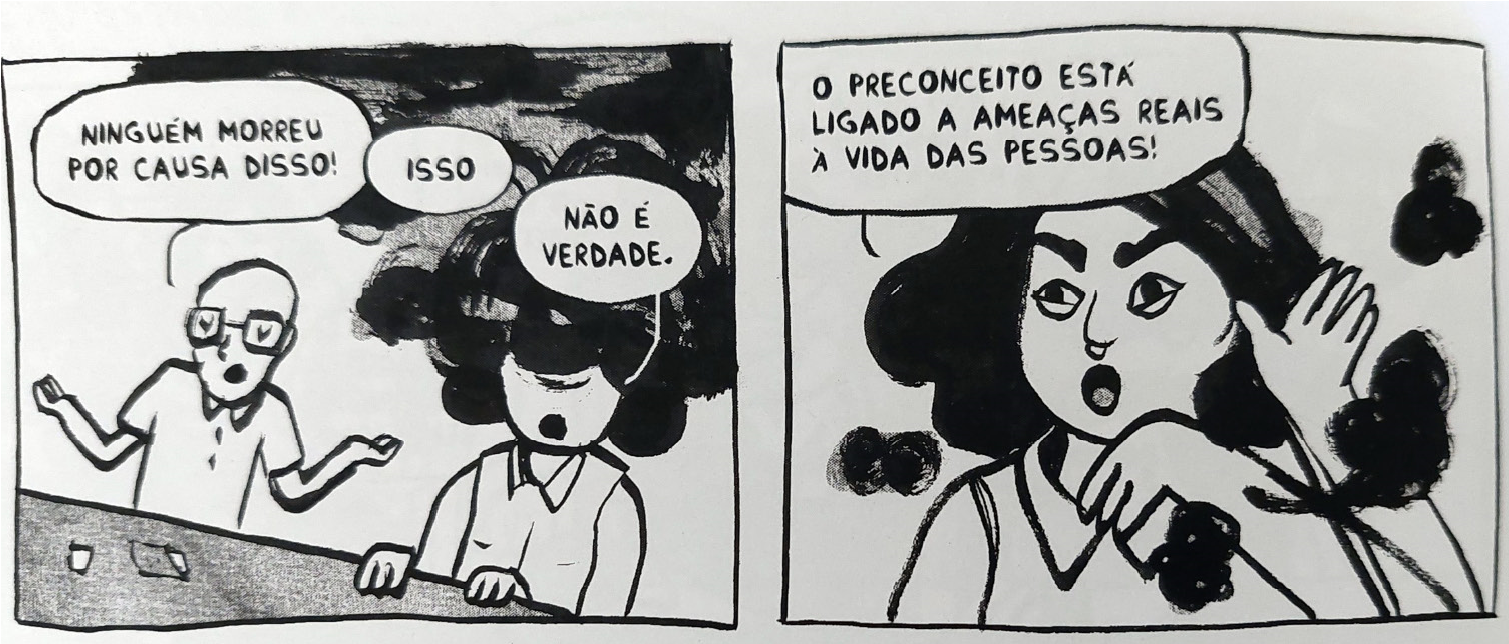

The stories recalled by Aline have as a common thread the author’s progressive political positions. As a non-binary and bisexual person, they do not intend to be “neutral” in the workplace. “Political memory” (Bosi, 2009) is understood as when the person who narrates the past is not content with only being a witness, even of their own story, but wishes to weave the reflection of the present with an ideological content that intervenes and reaffirms their position. This is evident in the story “Tempestade”, which recounts a conversation between teachers about prejudice occasioned by the same-sex relationship of two female students and the behavior of another student, Kevin. A teacher, represented by a white, male, and apparently older character (Figure 5), disdains the need to discuss “prejudice” and “homophobia” against the LGBTQIA+ community with the students. According to him, “no one died because of it” (p. 38).

Source. From “Tempestade”, by A. Lemos, 2021, in A. Lemos, Fessora!, p. 38. Copyright 2021 by Aline Lemos.

Figura 5 Comic “Tempestade”

The cloud in this story reinforces not only the atmosphere of the teachers’ room, but also appears in the further development of the discourse, which reproduces a symbolic violence - seen as the most “subtle” of oppressions (Bourdieu, 1994/1996). According to the author, symbolic violence is a social production since it is constructed by ways of seeing and thinking. This is, therefore, violence carried out from the hidden and silent complicity of those who suffer it and those who carry it out, since both suffer and act unconsciously (Bourdieu, 1994/1996). In the comic, by reproducing speech commonly used in the country to justify prejudice, the teacher is inflicting symbolic violence against the female students of class 8C, mentioned on the previous page so that we can conclude that both are LGBTQIA+. Aline, for their part, does not accept violence with apathy. Although stifled by the storm, the teacher takes a stand on the reality faced by LGBTQIA+ people, citing historical facts and even data of the violence that the community faces. They use Transgender research and the dossier of the National Association of Transvestites and Transsexuals that declare: “Brazil is a champion in the murder of transgender people. Today!” (p. 38).

In this act, we see not only the history teacher working in the environment, an image reinforced in the frame by the history books on the table, but also because they are a non-binary person who is affected by these discourses. This subject in the teachers’ room shows how there are teachers who reproduce prejudice and who are unprepared to deal with the different gender identities and sexuality of the student body. This issue can be understood as a collective experience within the country’s school communities, especially when we look at the data from the National Survey on the Educational Environment in Brazil 20165 (Secretaria de Educação da Associação Brasileira de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais, 2016). According to the survey, comments against LGBTQIA+ people in Brazilian schools is widespread, which contributes to the creation of a hostile school environment and signals to students that they are not welcome in that school community.

The survey further reveals that “almost half (47.5%) of LGBT students reported having heard other students making derogatory comments, such as ‘bicha’’, ‘sapatão’ or ‘viado’, often or almost always in the educational institution” (Secretaria de Educação da Associação Brasileira de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais, 2016, p. 31). In addition, the data collected shows that one-fifth of these students heard LGBTphobic comments in the educational institution, with 21.7% saying that such comments were made by most of their peers. Along the same lines, more than two-thirds of the students (69.1%) “reported that they have heard LGBTphobic comments made by teachers or other employees of the educational institution” (Secretaria de Educação da Associação Brasileira de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais, 2016, p. 31). In contrast, when teachers witnessed situations of LGBTphobia, “few students reported that their peers always or most often intervened when they heard LGBTphobic comments (25.6%), and more than a third (36.2%) said that their peers never took any action” (p. 31).

The lack of preparation of teachers and the school community is pointed out in the 2016 survey as a cause for the sense of not belonging and insecurity of students in Brazilian educational institutions. Therefore, when asked about whether or not to denounce the situations of violence and prejudice experienced in these spaces, many pointed out the lack of trust, the existence of prejudice, “shame, fear of reprisals and public exposure of the fact of being LGBT, even not believing in the possibility that the institution would take some effective action and denounce the situation” (Secretaria de Educação da Associação Brasileira de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais, 2016, p. 43).

In Fessora!, this unpreparedness revealed in the national statistics is visible in everything presented to us in “Tempestade”, especially in the words of the educators. From the teacher’s laughing at the students’ ‘mimicking’ of Kevin, to the trivialization of violence contained in the words of another teacher who calls “prejudice, homophobia (...) tempest in a teapot (...) no one dies from it” (pp. 38-39), and up to the principal’s refusal to deal with the issue, leaving it up to the families by saying that it is a “delicate” issue when Aline offers to talk to the class 8C students who are in a relationship.

Guizzo and Felipe (2016) analyze these challenges of school practices when teachers deal with this subject in the classroom. There is a slow approach to opening a debate on these inequalities by defining them as a “delicate” subject, one that is understood as being a transversal subject that is not always assimilated by the course subjects. Thus, the possibilities of change to reduce prejudice and promote the discussion that affects the lives of children and teenagers are lost, not only in the classroom, but also outside it.

“Tempestade” offers another story that begins and ends the comic: Kevin, the “blond kid in the 9th grade”. The student is described by teachers as noisy. They also say that Kevin is persecuted in the classroom by his classmates, which, in the opinion of the educators, is due to prejudice. We only understand the story of this student at the end of the comic: his mother caught him trying on women’s clothes at home. After that, Kevin “left” the school and no longer attended classes (Figure 6).

Source. From “Tempestade”, by A. Lemos, 2021, Fessora!, p. 39. Copyright 2021 by Aline Lemos.

Figure 6 Kevin in “Tempestade”

Kevin’s departure from school, even if it is a personal experience, is not only that; it reveals a collective, transpersonal experience, in that it represents a common situation in the daily lives of Brazilian LGBTQIA+ students, who face hostile environments in basic education schools. Failure to attend school is pointed out in the National Survey on the Educational Environment in Brazil 2016 (Secretaria de Educação da Associação Brasileira de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais, 2016) as a consequence of LGBTphobia, which can lead to school dropout, depending on the degree of violence and prejudice faced by students6. The research states that other consequences associated with the experiences of LGBTQIA+ students in hostile school communities include a drop in academic performance, depression, and the feeling of not belonging in the school.

Therefore, in a few frames Aline draws a memory in common with the life experiences of transsexual and transvestite people at school: involuntary evasion. Even though the violence happened at home, Kevin does not go to school much. This introduces vestiges of an experience of the “pedagogy of violence”7 (Andrade, 2012) by transsexual and transvestite students in Brazil. This process can also be “induced by the school, where members of the school community, symbolically or not, subject the students to embarrassing treatment until they cannot bear to live in that space, and they abandon it” (Andrade, 2012, p. 247). This reinforces the continuity of the cycle of exclusion of these individuals in society, who experience violence at home, at school, at work, in health care and in politics. Lima (2020), when analyzing these experiences of transsexual and transvestite people in education, observes that the school is a social space that reflects society. As an effect of this, it “produces and reproduces differences, distinctions and inequalities through multiple mechanisms of classification, ordering and hierarchization that are reinforced through a reference model to be followed” (Lima, 2020, p. 79), this model of hegemonic white, heterosexual, middle class and Christian in the daily school life (Junqueira, 2015; Lima, 2020; Louro, 2000). The exaltation of these social markers inside and outside the school is reflected in two experiences that are drawn in the comics “Besouro” and “Sovaco Cabeludo”.

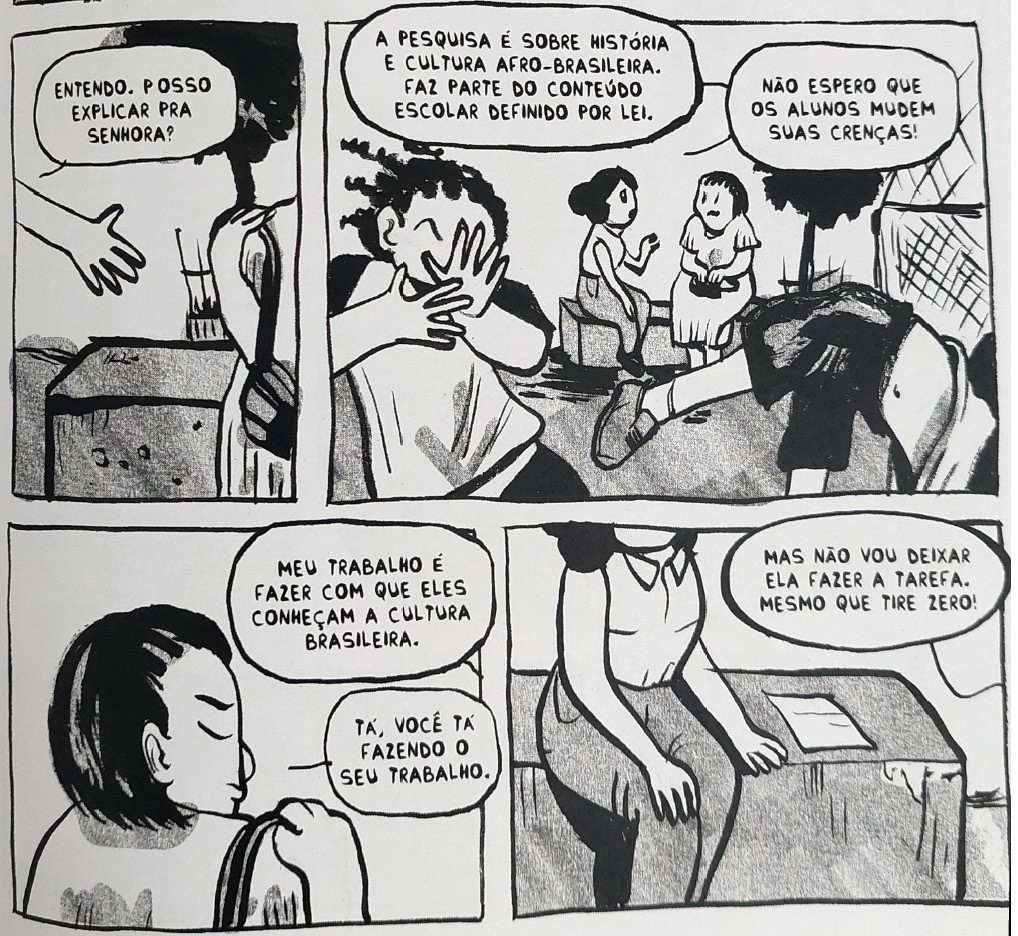

The title of the comic “Besouro” is a reference to the name of the Brazilian film released in 2009, which narrates the life of resistance and struggle of the capoeirista8 Manoel Henrique Pereira (1895-1924), known as Besouro, Besouro Preto, Besouro Mangangá or Besouro Cordão de Ouro. Aline presented this story in the classroom to the students during the discussion of Afro-Brazilian History and Culture, a subject enshrined by Law No. 10.639 (2003)9. The purpose of the law is to promote the different cultures of Brazil in education, reinforcing and valuing the histories of indigenous peoples and Afro-Brazilians, who have been systematically erased from the process of colonization until today. Abidias do Nascimento (1978), in O Genocídio do Negro Brasileiro, evidences the effort to “erase the memory of the African” (p. 84) and among the different social groups and individuals that aided in this project of the dominant ideology were historians, social scientists, literati and educators. The culture of the white man and European was desirable and emphasized in the official history of Brazil, and reflected in the school curriculum. This law seeks to break the continuity of the historical silencing of subordinated peoples in Brazil, but there is resistance to its implementation in everyday school life. This is clear when Aline presents the visit of a mother who questions the homework on the history of black people from the film Besouro (Figure 7): “my daughter isn’t going to do that assignment! And you shouldn’t teach those things!” (p. 49).

Source. Taken from “Besouro”, by A. Lemos, 2021, in A. Lemos, Fessora!, p. 49. Copyright 2021 by Aline Lemos.

Figure 7 Scene of the mother of a student criticizing the assignment on the film Besouro

The comic artist says that as “the white teacher” they “couldn’t even imagine” the challenges of teaching about the history of non-white peoples, in this case about the African matrix religions. Aline mentions a research paper (Botelho, 2019) that lays out the impasses experienced when teaching these topics: the exoticization and “folklorization” of the elements; the demonization for not being Christian or having European references; and racism. The shock is narrated by Aline when they face this reality at school. This made them adopt a comment to avoid misinterpretation by the students, as they emphasized: “I’m not asking you to adopt any religion, do you understand? I am saying that all beliefs must be respected” (p. 51). An issue that is not brought up when talking about Christian religions in the classroom.

The II Relatório sobre Intolerância Religiosa: Brasil, América Latina e Caribe (II Report on Religious Intolerance: Brazil, Latin America and the Caribbean; Santos et al., 2023) shows a 270% increase in violence against African-based religions10 in Brazil compared to the records kept between 2020 and 2021. This intolerance seeks to deny, erase, persecute or demonize the existence of the other through violence, ranging from symbolic to physical, against people and houses of worship.

This experience narrated by Aline sheds light on the debate of memory in dispute, where the school becomes a fundamental space to revive this subject from its forgotten status by teaching that there are numerous expressions of Brazilian identity (racial, gender, professional group, social class, among others) and telling stories outside the official version. To teach that the history of black people in Brazil is not limited to the period of slavery and, as Grossman (2000) points out,

to the extent that the only focus is on pain, people who have gone through a whole experience of survival and resistance end up being reduced to mere victims, and the fact that they are also survivors and resistant is not being taken into account. (p. 19)

The story of Besouro exposes the resistance and struggle for the right to manifest one’s own religion, without being criminalized or persecuted. In “Tempestade” and “Besouro”, the bias of political memory, whether individual or collective, is highlighted to help understand the challenges of the daily life of a history teacher with their students.

Aline is also the target of “joke” by three students for not conforming to a practice of femininity expected of a “woman”. By not shaving their underarms, the teacher also creates curiosity about sexuality. The initial pictures of the comic show the faces of the girls when they see the teacher’s hairy armpit, generating surprise and disgust (Figure 8).

Source. Taken from “Sovaco Cabeludo”, by A. Lemos, 2021, in A. Lemos, Fessora!, p. 52. Copyright 2021 by Aline Lemos.

Figure 8 “Hairy Armpit”

This joke relies on recreational racism, which is understood as a type of violence against black people when the jokes “portray blackness as a set of aesthetically unpleasant characteristics and a sign of moral inferiority” (Moreira, 2019, p. 19). The teenage students exemplified this dehumanization by reacting with the chorus of the song “Nega do Subaco Cabeludo” (Negress with the Hairy Armpit), by the humorist Pranchana Jack (2012), which became a meme in Brazil in 2012. In this song, recreational racism is evident in seeking to mask racial and gender prejudice with a hint of “humor”. This feminine image is associated with dirt that neglects hygiene. In qualitative research on the construction of black identity at school, Mizael and Gonçalves (2015) mention a white student who sings this song to the black female colleague, which “reveals how the white child perceives media influences and appropriates them, reproducing racial discrimination” (Mizael & Gonçalves, 2015, p. 12). Aline is associated with this negative image of the black woman in the lyrics.

Their intention to provoke a reaction in the teacher with the music was thwarted, because Aline also sings along to spoil their joke. In the end, the latter has the opportunity to explain the reason for choosing not to shave and questions the aesthetic standards placed on women. Although the adolescents observe that this is an “unhygienic” act and something that the “boyfriend may find bad”, the teacher is able to reflect with the students so they understand that men do not shave and no one associates that with poor hygiene; and that the boyfriend does not get to decide what they can and cannot do with their body. The brief conversation ends with another curiosity answered about Aline’s sexuality: “I said she had a boyfriend!” the teenager comments to her friend.

The students resort to the stereotype of what it is to be a woman. A stereotype is understood as a “set of beliefs, values, knowledge, attitudes that we consider natural, transmitted from generation to generation without question, and makes it possible for us to evaluate and judge things and human beings positively or negatively” (Chauí, 1997, p. 116). Aline presents us with the various daily aggressions using stereotypes that promote discrimination and the maintenance of hegemonic thinking in school with the crossing of gender, sexuality, race, and social class. The perpetuation of these discourses reinforces symbolic violence, the pedagogy of violence and, consequently, removes children and adolescents from the classroom when they do not fit into these spaces.

5. “What Appears to us as Unity Is Multiple”

Ecléa Bosi (2009) sees this multiplicity of memory as being like the unraveling of yarn into different skeins, “because it is a meeting point of various paths, it is a complex point of convergence of the many planes of our past” (p. 413). Looking at the narrative of life as a teacher for a semester, we analyze some of these discursive points that are not only the individual memory (a unit) that is being remembered, but also one that is collective. The school community represented by the characters of the principal, teachers, students, mother and janitor share the same event with Aline, but may have different perspectives and interpretations - either by ideological positioning or by the cultural and social repertoire, for example - as they were perceived in the comics. Stories that are part of the memory of the category of work and that move away from the stereotype of what it is to be a teacher11 in a cultural product such as comics.

Understanding this potential of the work done in Fessora! from the individual point of view on the experience of teaching in public schools is to present readers with a part of the complexity of education in Brazil. Guided by questions about mental health, challenges of the school in welcoming and debating gender identity and sexuality, and promoting educational practices that question sexism, racism, and homophobia in the daily life of the school that is sometimes attenuated under the pretext of making a “joke” about the school mate or the alleged absence of such prejudices.

The ending story, “Despedida” (Farewell), underscores the very expectation of being a teacher: the image of a figure who could transform students and assist in the critique of their own reality in a semester. “I don’t know what I expected./Tears?/Party?/How vain of me! To think it would make a big impact!/I was the one who was affected” (p. 64).

It is important to point out that, with this work, we do not pretend to have exhausted all the discussions and debates around Aline Lemos, their comic book Fessora!, and the topics addressed in it. Nor is that possible. What we did was to choose and make clippings within our research universes in line with the dialogical possibilities of our trajectories and investigations carried out so far. We, therefore, encourage researchers to pick up on our work in search of other possible analyses within this observed universe, exploring, for example, the other narratives and themes present in Fessora! or the trajectory of Aline Lemos as an independent comic artist in Brazil.

REFERENCES

Alves, N. C. F. (2021). Quadrinizadas: O feminismo negro e as personagens de Ana Cardoso, Dika Araújo e Flavia Borges [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro]. [ Links ]

Amaral, M. G. T. de, & Santos, V. S. dos. (2015). Capoeira, herdeira da diáspora negra do Atlântico: De arte criminalizada a instrumento de educação e cidadania. Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, (62), 54-73. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-901X.v0i62p54-73 [ Links ]

Andrade, L. N. (2012). Travestis na escola: Assujeitamento e resistência à ordem normativa [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade Federal do Ceará]. Repositório Institucional UFC. https://repositorio.ufc.br/handle/riufc/7600 [ Links ]

Arfuch, L. (2003). O espaço biográfico: Dilemas da subjetividade contemporânea (P. Vidal, Trad.). Editora Uerj. (Trabalho original publicado em 2002) [ Links ]

Arfuch, L. (2013). Memoria y autobiografía: Exploraciones en los límites. Fce Fondo de Cultura Economica. [ Links ]

Bosi, E. (2009). Memória e sociedade: Lembranças de velhos. Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Botelho, D. (2019). Religiões afro-indígenas e o contexto de exceções de direitos. In F. Cássio (Ed.), Educação contra a barbárie: Por escolas democráticas e pela liberdade de ensinar (pp. 107-114). Boitempo. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1996). Razões práticas: Sobre a teoria da ação (M. Corrêa, Trad.). Papirus. (Trabalho original publicado em 1994) [ Links ]

Carlotto, M. S. (2010). Síndrome de burnout: O estresse ocupacional do professor. Editora da Ulbra. [ Links ]

Chauí, M. (1997). Senso comum e transparência. In J. Lerner (Ed.), O preconceito (pp. 115-132). Imprensa Oficial do Estado. [ Links ]

Grossman, J. (2000). Violência e silêncio: Reescrevendo o futuro. História Oral, (3), 7-24. https://doi.org/10.51880/ho.v3i0.19 [ Links ]

Guizzo, B. S., & Felipe, J. (2016). Gênero e sexualidade em políticas contemporâneas: Entrelaces com a educação. Roteiro, 41(2), 475-489. https://doi.org/10.18593/r.v41i1.7546 [ Links ]

Halbwachs, M. (1999). A memória coletiva (L. L. Schaffter, Trad.). Editora Vértice. (Trabalho original publicado em 1950) [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2010). Censo de 2000. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/ pesquisa/23/22107 [ Links ]

Junqueira, R. D. (2015). Pedagogia do armário e currículo em ação: Heteronormatividade, heterossexismo e homofobia no cotidiano escolar. In R. Miskolci (Ed.), Discursos fora de ordem: Deslocamentos, reinvenções e direitos (pp. 277-305). Annablume. [ Links ]

Lage, N. B. (2022). Aconteceu comigo: Mulheres, narrativas e violências nos quadrinhos de Laura Athayde [Tese de doutoramento, Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica de Minas Gerais]. Banco de Dissertações/ Teses do Posling. https://sig.cefetmg.br/sigaa/verArquivo?idArquivo=4535452&key=7c8be1e2b4287e2e4 1aeadb9c0bc52db [ Links ]

Lei n.º 10.639, de 9 de janeiro de 2003. (2003). https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2003/l10.639.htm [ Links ]

Lemes, A. (2005). A escola do Chico Bento: Uma análise cultural. In Anais do 15º congresso de leitura do Brasil (pp. 1-15). http://alb.com.br/arquivo-morto/edicoes_anteriores/anais15/Sem13/adrianalemes.htm [ Links ]

Lemos, A. (2021). Fessora! Belo Horizonte, MG: Aline de Castro Lemos. [ Links ]

Lima, T. (2020). Educação básica e o acesso de transexuais e travestis à educação superior. Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, (77), 70-87. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-901X.v1i77p70-87 [ Links ]

Louro, G. L. (2000) Pedagogias da sexualidade. In G. L. Louro (Ed.), O corpo educado: Pedagogias da sexualidade (pp. 7-34). Autêntica. [ Links ]

Ministério da Saúde. (2018). Distúrbio de Voz Relacionado ao Trabalho - DVRT. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/disturbio_voz_relacionado_trabalho_dvrt.pdf [ Links ]

Mizael, N. C., Gonçalves, L. R. D. (2015). Construção da identidade negra na sala de aula: Passando por bruxa negra e de preto fudido a pretinho no poder. Itinerarius Reflectionis, 11(2), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.5216/rir.v11i2.38792 [ Links ]

Moreira, A. (2019). Racismo recreativo. Pólen; Sueli Carneiro. [ Links ]

Nascimento, A. (1978). O genocídio do negro brasileiro: Processo de um racismo mascarado. Editora Paz e Terra S/A. [ Links ]

Nascimento, K., & Seixas, C. (2020). O adoecimento do professor da educação básica no Brasil: Apontamentos da última década de pesquisas. Educação Pública, 20(36). [ Links ]

Oliveira, D. A., & Vieira, L. M. F. (Eds.). (2013). Pesquisa sobre trabalho docente na educação básica no Brasil: Sinopse do survey nacional. Gestrado/UFMG. [ Links ]

Postema, B. (2018). A estrutura narrativa dos quadrinhos: Construindo sentidos a partir de fragmentos. Pierópolis. [ Links ]

Pranchana Jack. (2012). Nega do subaco cabeludo [Música]. Aurélio; Iago Sonor. [ Links ]

Ramos, P. (2009). Histórias em quadrinhos: Gênero ou hipergênero? Estudos Linguísticos, 38(3), 355-367. [ Links ]

Ramos, P. (2011). Faces do humor: Uma aproximação entre piadas e tiras. Zarabatanas Books. [ Links ]

Ramos, P. (2014). Tiras livres: Um novo gênero dos quadrinhos. Marca de Fantasia. [ Links ]

Reimberg , C. O., Souza, D. M. de, Silva, J. P. da, & Oliveira, J. A. (2022). Condições de trabalho e saúde dos professores no Brasil: Uma revisão para subsidiar as políticas públicas. Fundação Jorge Duprat Figueiredo de Segurança e Medicina do Trabalho - Fundacentro. [ Links ]

Romualdo, E. C. (2000). Charge jornalística: Intertextualidade e polifonia - Um estudo de charges da Folha de S.Paulo. Eduem. [ Links ]

Santos, M. N., Marques, A.C., Nunes, I. J. (2012). Condições de saúde e trabalho de professores no ensino básico no Brasil: uma revisão. EFDeportes, (166). [ Links ]

Santos, C. A. I. dos, Dias, B. B., & Santos, L. C. I. dos. (2023). II Relatório sobre intolerância religiosa: Brasil, América Latina e Caribe (1.ª ed.). Centro de Articulação de Populações Marginalizadas; Observatório das Liberdades Religiosas. [ Links ]

Secretaria de Educação da Associação Brasileira de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais. (2016). Pesquisa nacional sobre o ambiente educacional no brasil 2016. https://educacaointegral.org.br/ wp-content/uploads/2018/07/IAE-Brasil-Web-3-1.pdf [ Links ]

1Artist, comic artist and illustrator from Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, self-declared non-binary person (their pronouns are elu/ela). They wrote “dozens of zines and books such as Artistas Brasileiras (Brazilian Artists; 2018), published in partnership with the publisher Miguilim - which earned them the 31st HQ Mix Trophy (2019) in the Homage category - and independent publications such as Fogo Fato (2020) and Fessora! (2021), both made possible by crowdfunding. They collaborated with publications such as Folha de São Paulo, A Zica, Plaf!, Banda and Mina de HQ, and were a teacher in the courses Vidas, quadrinhos e relatos, financed by the Municipal Law of Incentive to Culture (BH) - which resulted in a book of the same name - and FIQ-Jovem, of the Municipal Foundation of Culture of Belo Horizonte. In addition, they are founding member of the group ZiNas (2014) with which they published the zines Transa (2014) and Aborto (Miscarriage; 2015) and the book Vida, Quadrinhos e Relatos (Life, Comics and Stories; 2017)” (Lage, 2022, p. 292).

2Aline holds a bachelor’s and master’s degree in History from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, as well as complementary training in design and fine arts. As reported in the comic itself, four years after applying for a vacant position, Aline was summoned to the classroom. At the time, they were already studying on their way towards the arts, but they needed a job and so they stayed one semester in the school. This experience is portrayed in Fessora!.

3Charge, according to Paulo Ramos (2009), is a text of humour (which can contain images/illustrations/drawings and words) that deals with facts or themes linked to the news. According to the author, it is no coincidence that they are usually published in the politics or opinion section of newspapers. This is because politicians are often a great source of inspiration for cartoonists, who tend to portray them in a caricatured way. Thus, by establishing an intertextual relationship with the news, cartoons to some extent recreate the facts in a fictional way (Romualdo, 2000).

4According to the ideas of Alves (2021, p. 59), there is in these drawings of themselves a “visual parrhesia “ when women artists draw their bodies without adaptations to a current ideal of beauty, without seeking a body aesthetic disguised and distant from their real bodies and without caring about the rejection of the work, the criticisms and the violence as a result of this choice.

5At the time of delivery of this work, this was the most recent research found by the authors that maps the situation of LGBTphobia in Brazilian schools.

6According to the 2016 survey, “students were twice as likely to miss the educational institution when they had experienced higher levels of discrimination related to their sexual orientation (58.9% compared to 23.7%) or their gender identity/expression (51.9% compared to 25.5%)” (SEABLGBTT, 2016, p. 47).

7The pedagogy of violence does not happen only in school; it is in all instances of life where subjects learn pre-established discourses as a single truth. In the conception of Andrade (2012), this expression is linked to the aesthetics of prejudice and death. In this case, those who do not follow the hegemonic performance of gender are seen as “unnatural”, “unwanted” and the target of hatred and violence.

8Capoeira is not just a sport. It is understood as “an aesthetic and fighting expression that dates back to Afro-Brazilian ancestry, capable of transmitting, through the game and its music, the denied contents of the history and culture of blacks in Brazil” (Amaral & Santos, 2015, p. 54).

9In 2008, Law No. 10 639 (2003) was modified by Law No. 11,645, which also included the teaching of indigenous history and culture in the school curriculum.

10According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (2010), 0.3% of the Brazilian population declared itself a practitioner of Afro-Brazilian religions (umbanda, candomblé, pajelança and others).

11Idealization observed in the analysis of Adriana Lemes (2005) on the social representation of teaching, with Professor Dona Marocas, character of the comic Chico Bento by Mauricio de Souza that takes place in the Brazilian rural environment. The feminization of work, clothes and accessories that stretches between the voluptuous curves of the body and the disciplined bun in the hair, glasses and small earrings. This, in addition to the discourse of unconditional love for the profession even when it is not well paid.

Received: March 31, 2023; Accepted: August 26, 2023

texto em

texto em