Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

versão On-line ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.8 Braga dez. 2021 Epub 01-Maio-2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.3517

Articles

"Who Wants to Be Erased?" Images of Women in History Textbooks in Mozambican Education

1 Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

2 Centro de Humanidades da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Universidade Católica de Moçambique, Maputo, Moçambique

In this article, we discuss how women are portrayed in the current history textbooks of the general secondary education in Mozambique: what is the place of women in the history of Mozambique? Which women have a name, a face or a voice in the textbooks? How is women historical agency described? To answer these questions, we conducted a synchronic, multimodal and comparative analysis of how the history textbooks of 11th and 12th grades portray women. The analysis reveals profound asymmetries in the gender representations, both regarding the teaching content and the sources and iconography. The textbooks provide a historiographical framework based on male leadership while women appear confined to traditional gender roles, with rare exceptions. In light of the scarcity of studies concerning gender representations, intersectionality and history education in Mozambique, we analyse how text and image contribute to the erasure of women's agency in history textbooks. We pay particular attention to the pictures of women and discuss images' potential for combating sexism and decolonising knowledge.

Keywords: Mozambique; history education; cultural memory; decoloniality; (in)visibilities

Neste artigo iremos discutir a forma como as mulheres são representadas nos manuais de história em vigor no segundo ciclo do ensino secundário geral em Moçambique: qual o lugar das mulheres nos manuais na história de Moçambique? Quais as mulheres com nome, com rosto ou com voz nos manuais escolares? Como é descrita a sua agência histórica? Para responder a estas questões realizámos uma análise sincrónica, multimodal e comparativa da forma como as mulheres são representadas nos manuais de história da 11.ª e da 12.ª classes. A análise efetuada demonstra profundas assimetrias nas representações de género, quer no que concerne aos conteúdos de ensino, quer no que toca às fontes e à iconografia. Os manuais apresentam um quadro historiográfico assente na liderança masculina, enquanto as mulheres são apresentadas confinadas aos papéis tradicionais de género, com raras exceções. Tendo em conta a escassez de estudos referentes às representações de género, interseccionalidades e ensino de história em Moçambique, neste trabalho, analisamos o modo como texto e imagem contribuem para o apagamento da agência das mulheres nos manuais escolares de história. Prestamos particular atenção às imagens de mulheres e discutimos o potencial das imagens para o combate ao sexismo e para a descolonização do conhecimento.

Palavras-chave: Moçambique; ensino da história; memória cultural; decolonialidade; (in)visibilidades

Introduction

Various studies on the national history narratives and the dynamics of cultural memory in Mozambique have recently been developed (e.g., Khan et al., 2019; Schefer, 2016). However, research on history textbooks in Mozambican education is still scarce, and studies bridging this topic with gender representations and intersectionality are even scarcer.

As "places of memory" (Nora, 1989), the textbooks have been a privileged vehicle for disseminating the "official memory" of the nation (Pollak, 1989), but also one of the main forums of education for citizenship and peace. Textbooks are, in fact, a complex cultural product where scientific, pedagogical, political, socio-economic and artistic issues intersect. Currently, in most countries, the production of textbooks is subject to a series of regulatory measures by several institutions at international and national levels. They aim to ensure a set of "good practices", among which we highlight the promotion of gender equality and the respect for cultural diversity. This article will focus on the textbook as an unavoidable object of memory policies and a pedagogical tool for deconstructing social stereotypes and citizenship education (e.g., Carretero et al., 2017).

This paper intends to expand the study of images in history textbooks with a decolonial and intersectional approach (Mignolo & Walsh, 2018; Pereira et al., 2020) as the primary focus. As such, we will pay particular attention to the images that portray women (alone or accompanied; identified by name or not) and how these images articulate with the text. We intend to verify which women have a face, a name, and a voice. We will verify if the women who are named are mentioned in the text or if they only appear in the images as mere illustrations. We also intend to discuss the potential role of these images in decolonising knowledge.

Thus, in this article, we will focus our attention on the iconic dimension of textbooks. Starting from a decolonial and intersectional analytical framework (Cabecinhas & Mapera, 2020), we examine the images featured in the textbooks, assuming that each person belongs to multiple social groups — socially constructed in terms of gender, ethnolinguistic group, age, social class, among others — with asymmetric positions in a given society.

In Mozambique, the liberation struggle was portrayed as a struggle against two primary forms of oppression — the "colonial" and the "traditional". Within Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO; Front for the Liberation of Mozambique)1, there was debate about the emancipation of women, which was considered fundamental to the attainment of national liberation, as Eduardo Mondlane stated in 1967, at the time of the creation of the Destacamento Feminino (DF; Women's Detachment): "we will let women come here to Nashingwea for training. They will show whether or not they are capable of being a military force as well" (Mondlane, 1967, as cited in Zimba, 2012, p. 29). Concurrently, in 1973, Samora Machel (as cited in Zimba, 2012) defined "DF as a crucial instrument for women's political training and liberation" (p. 30). In the opening speech of the "Primeira Conferência da Mulher Moçambicana" (First Mozambican Women's Conference), Samora Machel (1973) stated:

the emancipation of women is not an act of charity. It is not the result of a humanitarian imposition or compassion. Women's liberation is a fundamental need to the Revolution, a guaranteeing its continuity, a condition for its triumph. ( ... ) How can the Revolution triumph without liberating women? Is it possible to liquidate the exploitation system and keep part of society exploited? ( ... ) How then can the Revolution succeed without mobilising women? If more than half of the exploited and oppressed persons are women, how can we leave them outside the struggle? (p. 47)

This intersectional framework is particularly relevant and challenging in the Mozambican context since the national liberation struggle aimed to dismantle all kinds of oppressions and thus create a nation free from any type of discrimination, such as racism and sexism.

In the following sections, we will briefly present the analytical framework and the context of our research, particularly concerning public memory and history education in Mozambique. Then, we provide an intersectional analysis of four history textbooks referring to the second cycle of general secondary education — 11th and 12th grades — published by different publishers — Plural Editores and Texto Editores2 — all following the curriculum approved by the Ministério de Educação e Desenvolvimento Humano (MINED; Ministry of Education and Human Development).

Decolonisation of Thought, Intersectionality and History Education in Mozambique

History education has been regarded as a pivotal instrument in the nation-building process. Like other instruments of the state, history education establishes guidelines about what should be forgotten and what should be remembered from the nation's past. It thus cementing a link between dominant systems of meaning or hegemonic social representations (Jodelet, 1991) and personal experiences and trajectories. Some studies acknowledged the long-term impact of textbooks in shaping young people's worldviews (e.g., Ide et al., 2018), hence the particular importance of this study.

As Wertsch (2002) underlines, official history and public memory are closely related, stemming from a selective process of construction of the past in a given cultural context. This process cannot be understood without considering the asymmetric power relations between groups, cultural symbols and current agendas. Recent studies conducted in several countries across continents suggest that history textbooks rarely challenge dominant narratives of the nation (e.g., Cajani et al., 2019). For instance, in the current Portuguese secondary school textbooks, the images selected to illustrate historical concepts, events, and personalities, implicitly convey hierarchies of humanity that reinstate colonial hierarchies and clearly show which are the ''lives that matter'' and which are systematically ''erased'' (Cabecinhas, 2018).

In an incisive chronicle published in the newspaper Sol about 1 decade ago, Nataniel Ngomane (2012) ironically asked, "Lusophony: who wants to be erased?" (p. 24). Ngomane denounces the Lusocentric version of history that he forcefully learned at school in Mozambique during the Estado Novo period. He learned about Portuguese heroes but learned nothing about Mozambican heroes. The title of this chronicle provided us with the inspiration for a series of studies conducted within a vast research programme on social representations of history, questioning the lines of rupture and the lines of continuity between the colonial and the post-colonial.

In Ribeiro's (2015) view, colonial education met three principles: the expansion of faith, civilisation through assimilation, and work to safeguard dignity. This conception of education was conducive to the silencing of the local people's history and culture and the disinvestment in quality education for all the fringes of the population. In effect, census data from 1970 showed an 89.7% illiteracy rate in Mozambique (Mazula, 1995).

In Mozambique, upon the advent of national independence in 1975, there was a clamour for an education able to prepare Mozambicans free from the mentality inculcated during the colonial period. As Castiano (2019) underlines, Samora Machel considered education "a task for all of us", and behind this idea of "all" was the "'massification' of education: children, young people, adults, workers, peasants, soldiers, civil servants, production and consumer cooperatives" (p. 276). According to Castiano (2019), the education system outlined then was based on "the denial of colonial and traditional 'values'. Education should combat the 'sequels' of the colonial man, such as elitism, racial discrimination and individualism embodied in the exploitation of man by man (capitalism)" (p. 276). As for the "'sequels' of tradition education had to fight against, they included tribalism, obscurantism, ethnocentrism and discrimination of women" (Castiano, 2019, p. 277).

Law No. 4/83 (Lei n.º 4/83, 1983) approved the National System of Education having "as its central objective the education of the New Man, a man free from obscurantism, superstition and bourgeois and colonial mentality, a man who assumes the values of socialist society" (p. 24-(14)), with "a national, patriotic, revolutionary and internationalist conscience" (p. 24-(16)). According to this document, "teaching should encourage the link between theory and practice", the "close connection between the school and the community", and "preserve and develop the cultural heritage of the Nation" (Lei n.º 4/83, 1983, p. 24-(14)). However, the nation-building process was based on eliminating local cultural manifestations, as they allegedly promoted regionalism, tribalism and obscurantism (e.g., Cabaço, 2007). Thus, local administrative structures (régulos) were contested since they were the same structures used by colonial administration (Cabaço, 2007). According to Ribeiro (2015), the history of Frelimo and the anti-colonial conquests were the main contents in the history textbooks of that period. The history of the nation was limited almost exclusively to the history of Frelimo.

From the 1990s, following the signing of the peace agreement, the holding of elections and the introduction of multipartyism, Mozambique redefined its economic and education policies (Jamal, 2019). Law No. 6/92 (1992) on the National Education System was approved to adapt education to the national and international context, replacing Law No. 4/83. These reforms aimed not only at introducing an educational model aimed at the global market, but also economic and cultural cooperation. A curriculum review is initiated, culminating in the approval of the primary school curriculum plan in 2004 and the general secondary school curriculum plan in 2008 to foster a "multicultural education" (Jamal, 2019). Thus, new educational goals are introduced, emphasising the recognition of cultural, ethnic, religious and political diversity (Jamal, 2019). To what extent have such goals been achieved?

Meneses (2017) describes the Mozambican nation as the outcome of a collection of past memorial references linked to a political elite, aiming at the affirmation and legitimation of its hegemony. According to the author, the nation's official memory is written from the South and disseminated throughout the country, silencing the diversity of memories.

Mueio (2019) states that the National Education System, notably the curriculum plan of general secondary education, advocates the approach to gender and equity transversally in all subjects. To assess this transversality in grade 10 of general secondary education, Mueio (2019) observed, in a school unit in Boane, Maputo, the normative documents of the Portuguese curriculum and the textbooks and the teaching of Portuguese language and geography. As part of this work, Mueio (2019) noted that each teacher approaches the gender issues in their way, which, in the author's opinion, has a positive impact on the students' understanding of gender and equity issues. However, according to the author, the communities where the students belong do not improve this understanding.

Mueio (2019) argues that, when addressing cross-cutting topics, teachers face constraints related to cultural aspects of the school's setting. These constraints are related to issues that are taboo in certain regions, which makes it challenging to approach specific topics, such as, for example, early pregnancy and sexual harassment. From this observation, in both subjects (Portuguese Language and Geography), the author concluded that "gender" is taught resorting to expository and not transversal methods. Hence, Mueio (2019) proposes to envisage cross-cutting, interdisciplinary and learner-centred teaching methods.

Some Mozambican authors have suggested that the approach adopted by textbooks to the issue of the ethnocultural representation of what should be taught in schools and on which the sociocultural development of a country like Mozambique relies could be revised, at least concerning some dimensions, namely those mentioned by Laisse (2020) and Silva (2013).

Focusing on an approach to Portuguese language textbooks for 11th and 12th grades, Laisse (2020) demonstrated that in these resources, as far as the teaching of literature is concerned, the literary canon taught in schools is not representative of all Mozambican ethnic groups. Meanwhile, Silva (2013) studied the intercultural education and the iconographic representation of Mozambicans in primary education textbooks (first, second and third grades). He observed that the social reality portrayed in the textbooks is restrictive and prone to create prejudices among students since it is not inclusive in representing the different Mozambican ethnic groups. In this regard, the author states:

looking at these images of Mozambican people, whoever observes them, urban or peasant, is aware and fully convinced that only black coloured people inhabit Mozambique. The cultural value of "multiracialism" is completely forgotten in this textbook, which is serious. It does not represent the social reality of a country whose diversity of origins is fascinating and even in the process of unstoppable miscegenation. So how can we make children from the rural areas, for example, recognise a teacher or any non-black citizen as Mozambican? Are we not creating from an early age xenophobic assumptions and even epidermic prejudices? (Silva, 2013, p. 46)

The outcomes of these two studies are essential to consider aspects related to the teaching of local knowledge, which, according to Basílio (2012), are meant to give an epistemological status to the scientific and the cultural dimensions in Mozambique, thus contributing to the decolonisation of knowledge.

In this paper, our analysis focuses exclusively on the history textbooks currently in use in the 11th and 12th grades. The history textbooks approved by MINED are entirely written in Portuguese and produced by different publishers with international partners. The textbooks' content is produced locally, but editing and printing are usually conducted abroad. MINED defines the curriculum that publishers are expected to follow. The publishers choose the authors, and the ministry then selects evaluators. The evaluation focuses mainly on the textbook's verbal content and less on its layout, including images.

Before focusing on the textbooks' contents, it is important to briefly mention some of the goals of history education in the 11th and 12th grades and their corresponding curricula. Among the primary goals of the 11th-grade are: "identifying in history the role of communities in the national historical heritage"; "analysing the contents of the country's history as a contribution to the reinforcement of patriotic consciousness and national unity"; "understanding the dynamics of the country's history at social and socio-economic levels" (Instituto Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação [INDE], 2010a, p. 8).

The history curriculum for 11th-grade (H11) consists of five units: "1 Introduction to History; 2 Invasion, Partition and effective occupation of Africa; 3 Africa in the colonial period; 4 The National Liberation Movements 1880-1980; 5 African Problems Today: from 1960 to the present day" (INDE 2010a, p. 8). The program explains that the content on "nationalism" is related to the "Transversal theme: Cultural Identity and Mozambicanity" (INDE, 2010a, p. 16), suggesting the following approach to the subject:

we suggest the teacher guide the students to undertake short assignments on the role of some Mozambican nationalists who stood out in the struggle against the colonial system. Such as Eduardo Mondlane, Filipe Samuel Magaia, Noémia de Sousa, José Craveirinha, Rui de Noronha, Tómas Nduda and others. Regarding the MLN, the teacher [should] pay attention to the aspects related to the emergence of African Nationalism, starting from the sporadic peasant uprisings to the action of intellectuals until the formation of political parties. (INDE 2010a, p. 23)

The history curriculum for 12th grade (H12) consists of five thematic units, namely: "1 Periodisation of the History of Mozambique; 2 Mozambique - From the Primitive community to the emergence of exploration societies; 3 The States of Mozambique and foreign mercantile penetration; 4 The period of colonial domination in Mozambique; 5 Mozambique after independence" (INDE, 2010b, p. 8). The objectives of the 12th-grade curriculum include: "characterising the National Liberation Movement and the post-Independence period" and "critically interpreting and knowing how to substantiate the events of the world today, by understanding the structural functioning and evolutionary dynamics of societies in the 'States of Mozambique'" (INDE, 2010b, p. 12).

The 12th-grade curriculum explicitly requests that teachers approach the "post-Independence" period to "encompass the transversal themes related to the culture of peace, human rights, democracy; cultural identity and Mozambicanity as well as gender and equity" (INDE, 2010b, p. 32). However, that does not translate into the curricular contents. It is worth noting that the curricula explicitly mention several historical personalities to be addressed, but Noémia de Sousa is the only woman mentioned (INDE, 2010a, p. 23).

As we mentioned above, few studies address the gender representations in Mozambican history textbooks. We are not aware of any studies on how women are represented in the history textbooks produced by different publishers and currently in use in the second cycle of general secondary education.

Thus, in this study, we will make a synchronic, multimodal and comparative analysis of how 11th and 12th-grade history textbooks represent women from four axes: name (which women are named); face (which women are portrayed in images); voice (which women have their words quoted); social role (which social part is attributed to the women who are named, cited or portrayed).

We aim to ponder how the images featured in these textbooks can contribute to decolonising historical knowledge; and the extent to which the visual elements are in line with the text to convey a single vision of the nation. Bellow, we will describe the most relevant findings of our research. Firstly, we will focus on the 11th-grade textbooks and then on the 12th-grade textbooks.

11th-Grade Textbooks: The Erasure of Women in African History

As mentioned earlier, the 11th-grade history curriculum focuses entirely on the history of Africa. In Texto Editora's textbook H11 História 11ª Classe (H11 11th-Grade History), the "Invasion of the African Continent" is referred to as "a period marked by the effort to dominate the African continent undertaken by Europeans, to which Africans fought back with the means available to make this claim unfeasible" (p. 2).

This textbook does not feature a single image depicting women. No woman is named, nor are the words of any woman cited. Only the name "Queen Nzinga" in a map of Africa (p. 75) is displayed in the area corresponding to Angola as if it was the country's name. Still, nothing is said about this personality of Angolan history.

In this textbook, male hegemony is absolute at a visual level: all the historical figures portrayed are men, and the images used as chapter separators are all male persons3, reinforcing the naturalisation of male domination. Thus, in the textbook H11 História 11ª Classe, dedicated to the history of Africa, women are entirely erased as persons and as historical agents, that is, the history of Africa is presented as exclusively masculine.

In contrast, in the textbook História 11ª Classe (11th-Grade History) by Plural Editores, we observed an effort to include women in the history of Africa as we will explain below. However, history is still presented as a male enterprise, as illustrated in a figure explaining that "history is the science of men over time" (p. 11) and providing the following periodisation: Antiquity, Middle Ages, Renaissance, Modern Period and Contemporary Period. Our purpose is not to debate the complex questions inherent to the historical periodisation presented (Lorenz, 2017). However, interestingly this image, while seeking to situate the history of Mozambique in the universal history, by including the portrait of Eduardo Mondlane to symbolise the contemporary period, reveals the naturalisation of the erasure of women as historical agents, since the figures chosen to represent the various historical periods are all men.

The 11th-grade textbook by Plural Editores features some images with women, but these women are anonymous in most cases. Only seven women were named: Eugène Delacroix, Reinata Sadima, Eleanor Roosevelt, Joséphine Baker, Rosa Luxemburg, Noémia de Sousa and Amélia Souto. Only one woman has a voice: the historian Amélia Souto, whose book is cited. Below we will provide some of the images in which women are depicted and their respective captions.

Figure 1 shows an anonymous woman photographed in a cotton plantation in Sofala. This woman has a cotton sieve in her hand and a baby on her back. As we can see, the caption refers to an "African woman in a cotton plantation (Sofala, present-day)" (p. 56). This type of caption, referring to a generic description of the "African woman", is common in European textbooks. Still, we can wonder why such a caption is used in a Mozambican textbook. Maybe this type of caption may be because the design work of the textbooks in Mozambique — including pagination, choice of illustrations and their captioning — is handled by local publishers affiliated with Portuguese publishers.

Source. From História 11ª classe (p. 56), by J. Nhapulo e G. Cumbe, 2015, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 1 "African woman in a cotton plantation"

When addressing the slave trade, the textbook shows a photograph of a "Swahili tribal woman" (p. 76) without any further contextualisation. The text mentions that "the slave trade and its circumstances may have opened up a new relationship between local tribes and Europeans" (p. 76). One can infer that this photograph intends to illustrate one of these alleged "tribes".

Further on, the same textbook includes a picture of a young woman in the bush. Neither the explanatory text nor the photograph's caption ("young Azande woman, Congo", p. 78) identifies the person depicted, bare-chested and wearing a beaded necklace, which sets up a line of continuity with colonial visualities (e.g. Vicente, 2014). The explanatory text next to the photograph addresses the resistance movements in Sudan against the British authorities, stating that the Azande "led resistance actions, but had no better luck. They were defeated between 1905 and 1908" (p. 78).

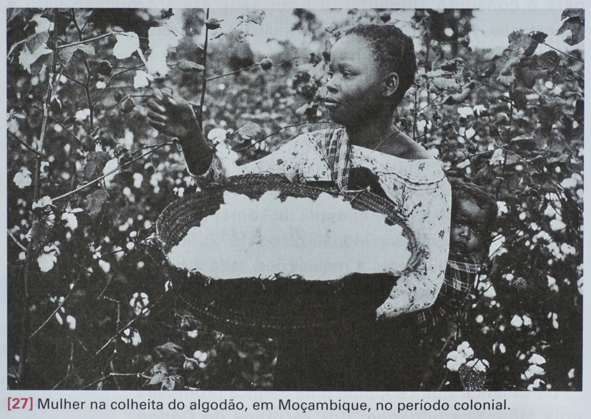

Further on, a photograph depicts an anonymous woman harvesting cotton (Figure 2). The caption reads, "woman harvesting cotton in Mozambique in the colonial period" (p. 114). The text encircling the photograph addresses "mining and agriculture" in southern Africa, specifying the differences between "British West Africa" and "French Africa" (p. 114).

Source. From História 11ª classe (p. 114), by J. Nhapulo e G. Cumbe, 2015, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 2 "Woman at the cotton harvest"

The Nhapulo and Cumbe's textbook dedicates two pages to the "action of women" in the liberation struggle, explaining that "their presence mixed feelings. On the one hand, they were fervent fighters, but, on the other hand, their femininity was contagious and distracted the supporters of the opposite sex" (p. 146). In this regard, the text includes a quote from Ki-Zerbo, from 1972, explaining that "the participation [of women] in the meetings, especially at night, naturally created serious sentimental and sociological problems" (p. 146). Interestingly, or perhaps not, no woman is quoted or referred to about "women's action" in the liberation struggle, although many gave their lives in that struggle.

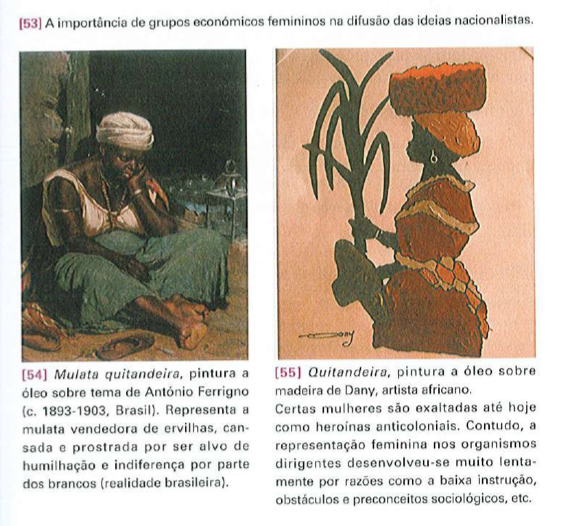

On the following page, the textbook presents two canvases on the “importance of women's economic groups in the spread of nationalist ideas” (Figure 3, p. 147). Regarding the first canvas, the caption explains that it "[re]presents the pea-selling mulatta, tired and prostrate for being humiliated and disregarded by whites (Brazilian reality)" (p. 147). On the second canvas, the caption explains that "some women are exalted even today as anti-colonial heroines. However, female representation in governing bodies evolved very slowly due to factors such as low education, obstacles and social prejudices" (p. 147). The names and actions of the women "exalted to this day as anti-colonial heroines" are not mentioned (p. 147). On that same page, students are given an exercise — "explain how women have been important in African political parties" — but no information is provided to allow students to do it properly.

Source. From História 11ª classe (p. 147), by J. Nhapulo e G. Cumbe, 2015, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 3 Greengrocers

In Nhapulo and Cumbe's textbook, only four women identified by name are portrayed: Eleanor Roosevelt, Josephine Baker, Rosa Luxemburg and Reinata Sadima. Thus, despite this textbook focusing on the history of Africa, only one of these women is African: the Mozambican artisan Reinata Sadima.

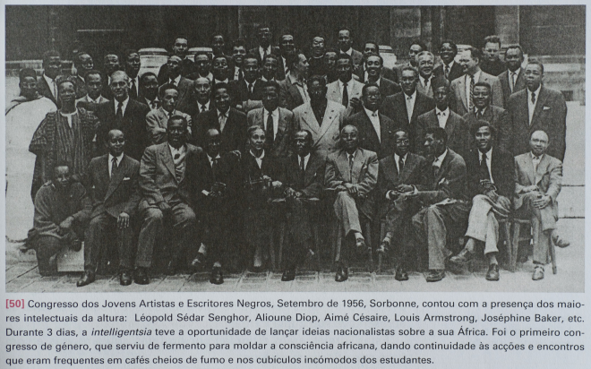

Rosa Luxemburg was mentioned among "various scholars" as part of different studies on imperialism: "several scholars, such as Vladimir Lenin, George Ledebour and Rosa Luxemburg have devoted themselves to this subject, but John Atkinson Hobson was considered the one which best explains the theory" (p. 71). Eleanor Roosevelt appears in a photograph on a page covering "trade unions in Africa". The photograph, untitled, includes the following caption: "Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Eleanor Roosevelt, one of the drafters of this fundamental document, reading its printed version in 1948" (p. 118). The text explains that the declaration mentioned above "defends the right to unionise and claim workers' rights" (p. 118). It further explains how trade unions fought "for improved working conditions, wage increases, the observance of internationally established working hours, specific treatment of the physiological specificities of women workers, the end of racial discrimination in the labour sector" (p. 118). It also affirms that "in the French and Portuguese colonies, there was evident racial discrimination in the workplace. However, trade unionism came late to Africa" (p. 118). However, there is no mention of such "physiological specificities of working women" nor the participation of women in trade unions in Africa (p. 118). The textbook shows a photograph (Figure 4) of the first "congress of young Black Artists and Writers, September 1956, Sorbonne" (p. 145). The photo caption states that this event:

was attended by the greatest intellectuals of the time: Léopold Sédar Senghor, Alioune Diop, Aimé Césaire, Louis Armstrong, Joséphine Baker, etc. For three days, the intelligentsia had the opportunity to launch nationalist ideas about their Africa. It was the first congress of its kind, which served as a leaven for shaping African consciousness. (p. 145)

Source. From História 11ª classe (p. 145), by J. Nhapulo e G. Cumbe, 2015, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 4 Congress of young black artists and writers

Some of the intellectuals referred to in this caption are later addressed in the textbook. However, there is no mention of the actions of Joséphine Baker, the only woman in the photograph. Since it included her name in the caption, it would have been pertinent to take the opportunity to include some information about her.

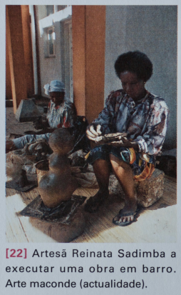

Reinata Sadimba4 is the only Mozambican woman named in a photograph (Figure 5), with the following caption: "artisan Reinata Sadimba making a piece in clay. Maconde art (present-day)" (p. 110). The text next to the picture addresses "the colonies purpose for the metropolis and the impact on African economy". It states, "one of the colonial economy's hallmarks was the raw materials exploitation and the dissuasion of any initiative aimed at industrialisation and transformation of raw materials and agricultural products" (p. 110). There is no mention of endogenous knowledge, of the "Maconde art" or the work of Reinata Sadimba, whose photograph seems to merely illustrate a specific raw material — clay — and not her artistic production.

Source. From História 11ª classe (p. 110), by J. Nhapulo e G. Cumbe, 2015, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 5 Reinata Sadimba, artisan

On the "driving forces of African nationalism", the textbook mentions the following: "African trade unions, the action of intellectuals; the action of political parties; student movements; the action of religions; the role of young people and the action of women" (p. 140). As for the role of intellectuals, it highlights that they "fought for the affirmation of the African 'I'. They claimed African authenticity as vital. ( ... ) The exchange with intellectual groups from other parts of the world opened new horizons. It brought new considerations to the legitimacy of colonialism" (p. 142). Noémia de Sousa's name is among a group of "intellectuals with a nationalist personality" — including José Craveirinha, Rui de Noronha, Rui Knofli and Rui Nogar — who assumed "their Africanity from their commitment to Mozambicanity" (p. 143). On that page, there is an exercise stating: "Eduardo Mondlane, Filipe Samuel Magaia, Noémia de Sousa, José Craveirinha, Rui de Noronha and Tomás Nduda, among others, have contributed much to the development of 'Africanity' and 'Mozambicanity'" and then calls on students to develop a paper "on one of these charismatic Mozambicans" (p. 143).

It is also worth noting that the only woman with a voice in the textbook is the Mozambican historian Amélia das Neves Souto, whose work Guia Bibliográfico (Bibliographic Guide) is cited on the "general characteristics of colonialism in Africa". In the author's words, "indigenous colonial policy was always defined according to the colonial power's economic, political and social interests. To defend these interests, the colonial administration has always felt the need to use traditional authorities" (p. 92). The other sources cited in the text in both textbooks dedicated to the history of Africa (11th grade) are men.

12h-Grade Textbooks: The Erasure of Women in Mozambican History

As we mentioned before, the 12th-grade history curriculum is entirely dedicated to the history of Mozambique.

The textbook H12 História 12ª Classe (12th-Grade History) by Texto Editora shows only one image of an anonymous woman and does not quote the words of any woman in the whole textbook. The textbook mentions "women" in general twice but refer to them as victims, compared to "cattle", as seen in the following quote:

Eurocentric historiography devalues the impact of anti-colonial resistances. Eurocentric historiography devalues the impact of anti-colonial resistances. European historians claim that the colonial wars of occupation served to impose order, peace, stability and tranquillity, since, before the arrival of Europeans, Africans fought among themselves for the expansion of kingdoms or the plundering of the cattle and women of the conquered [emphasis added]. (p. 86)

Some generic references about the different forms of social organisation, namely patriarchal and matriarchal societies, emerge in this textbook. Still, it does not give any personalised information about the agency of women in Mozambican history. It names five women — Eulália Maximiano, Josina Muthemba, Noémia de Sousa, Precilda Gumane and Sofia Pomba Guerra —, but these are generic mentions, among other names, as we can see in the following excerpt:

poets, painters, and writers also expressed their discontent towards colonialism. Men, such as Rui de Noronha, Malangatana, José Craveirinha, João Craveirinha, Noémia de Sousa, among others [emphasis added], in their poems, on their canvases, in their writings protested against the colonial situation. (p. 126)

We should note that Noémia de Sousa is the only woman whose name appears more than once in Mussa's textbook, but there is no information about her work, and none of her poems is cited. Furthermore, in the textbook's last section, which focuses on independent Mozambique, there is no mention of women in general or any woman in particular, and there is an abundance of photographs of men, identified by name and with specific information on their role in the history of the country after independence.

The textbook features only one image with a woman alone, seated on the ground, but she has no name or voice. It is a photograph with the following caption: "elderly woman protector of the rock paintings in Manica" (p. 14), which serves to illustrate the importance of archaeological sources.

The textbook also includes, almost unnoticed, another image depicting women. It is a photograph of the panel5 referring to the Ngungunyane6 prison in 1895 (p. 6), showing two women in the back, with their heads bowed. However, it does not mention the fate imposed on these women7.

In short, in the H12 História 12ª Classe (12th-Grade History) textbook by Texto Editores, devoted to the history of Mozambique, women are erased as persons and as historical agents. Although some women are named as members of the resistance to colonialism, they have no face or voice. Furthermore, the role of women in the armed struggle and the construction of independent Mozambique is omitted altogether.

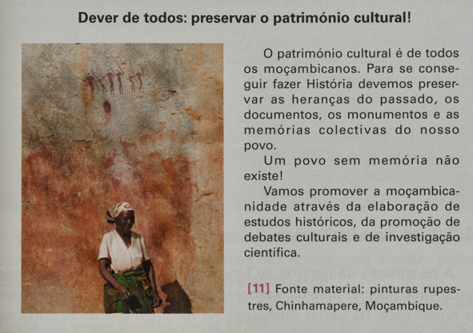

In contrast, in the História 12ª Classe (12th-Grade History) textbook by Plural Editores, some women are portrayed with a face and a name. However, most of the images refer to anonymous women. One example is illustrating the theme of cultural heritage through a photograph of cave paintings depicting an unidentified woman.

The image's caption (Figure 6) reads "rock paintings. Chinhamapere, Mozambique", with no reference to the woman depicted (p. 19).

Source. From História 12ª classe (p. 19), by J. Nhapulo, 2019, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 6 "Everyone's duty: preserve cultural heritage!"

When addressing the historical sources, the textbook mentions the role of the elders in the intergenerational transfer of knowledge in the oral tradition. It shows a photograph of an anonymous woman with her granddaughter (Figure 7), with the following caption: "grandmother and granddaughter, Maputo. The elders are like a book; they are a well of wisdom in the spoken form. The intergenerational transfer of knowledge is fundamental to the oral tradition" (p. 23).

Source. From História 12ª classe (p. 23), by J. Nhapulo, 2019, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 7 "Grandma and granddaughter, Maputo"

Several other photographs of anonymous women illustrate the "oral tradition" and the "intergenerational interaction" (women dancing, women with children), the work in the fields and religiosity. Throughout the textbook, various illustrations refer to motherhood, for example, an image of Our Lady with the baby Jesus (p. 13) and a canvas by the painter Malangatana, entitled "Mother's Cry" (p. 240), which evoke the role of women as mothers or in other kinship roles (grandmothers, wives, daughters).

Figure 8 features a photograph with the following caption:"the emperor Gungunhana and his wives" (p. 130). It depicts the emperor with the women who accompanied him upon his deportation to Lisbon, but they are not named.

Source. From História 12ª classe (p. 130), by J. Nhapulo, 2019, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 8 "Emperor Gungunhana and his wives"

In Plural Editores' textbook, there are few women mentioned, and, in most cases, they are mentioned at the end of a list of male names, without any additional information, as is the case of the Mozambican writer Paulina Chiziane, whose name appears at the end of a list of writers: "Ungulani Ba Ka Kossa, Mia Couto, Hélder Muteia, Pedro Chissano, Juvenal Bucuane, Paulina Chiziane and others" (p. 192). The following page shows the canvas "Olhos Brancos de Farinha de Milho" (White-Eyes of Maise Flour) (1961) by the painter Bertina Lopes8, "nicknamed by the colonialists as the 'revolted painter'" (p. 193).

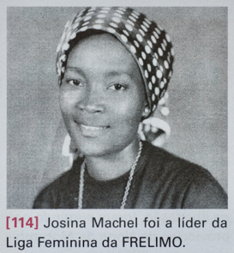

Two Portuguese women, linked to the Portuguese youth Movimento de Unidade Democrática (MUD) — Maria Fernanda Silva and Sofia Pomba — are named (Nhapulo, 2019, pp. 213-214). Noémia de Sousa and Josina Muthemba Machel are the only women portrayed in photography and identified by their names (Figure 9 and Figure 10, respectively). Mozambican writer Noémia de Sousa is referred to as a member of the Movimento de Jovens Democratas de Moçambique (Youth League of the Mozambique Democratic Movement; p. 214) and Josina Muthemba Machel as a leader of the Frelimo Women's League (Nhapulo, 2019, p. 219).

Source. From História 12ª classe (p. 214), by J. Nhapulo, 2019, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 9 Noémia de Sousa

Source. From História 12ª classe (p. 219), by J. Nhapulo, 2019, Plural Editores. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 10 Josina Machel

It is important to note that Josina Machel was the woman most often referred to in studies conducted with students on the social representations of the history of Mozambique. We do not discuss here the complexity inherent to the centrality of this personality in Mozambican collective memory. However, the fact that the date of her death was chosen as Mozambican Women's Day, a bank holiday celebrated every year on April 7, is not unrelated to this.

As for women with a voice, this textbook cites historians Amélia das Neves Souto and Tereza Cruz e Silva and mentions Janeth Mondlane (p. 220). Overall, the women named have engaged in political issues as activists, fighters or artists. Concerning women scientists, only historians whose work is cited as a source in the textbooks are mentioned.

The scarcity of women mentioned and their depiction contrasts with the objectives proclaimed when the Organização da Mulher Moçambicana (OMM; Mozambican Women's Organisation) was founded. As underlined then,

the Central Committee [of FRELIMO] has stated that one of the priority tasks of our struggle should be the struggle for the emancipation of women. This struggle should be an essential concern of all Mozambicans, both men and women. That will allow us to effectively mobilise the potential of Mozambican women in the fight against Portuguese colonialism and end the discriminatory and exploitative practices of traditional and colonial society towards women, enabling them to assume their role as citizens fully. (Voz da Revolução, 1972, p. 3)

Concluding Remarks

This paper analysed four history textbooks in use in the Mozambican education system, namely the 11th and 12th grades. We focused our attention on how women are represented in the textbooks by Plural Editores and Texto Editores. In our analytical framework, we considered four axes regarding the (in)visibility of women in the textbooks, namely: name (which women are named); face (which women are portrayed in images); voice (which women have their words cited); social role (which social part is assigned to the named, mentioned or portrayed women). Concerning the women depicted, we looked at other dimensions, namely the type of framing and whether the women were portrayed alone or accompanied, and the type of caption (generic or personalised, for example).

The textbooks analysed have few or no images of women identified by name. Overall, the references to women are very vague and suggest a homogenisation of women, with very few cases of personalised information on women's actions as historical agents. The only exception is Noémia de Sousa's social role, promoted together with other nationalists, in the struggle for Africanity and Mozambicanity, in line with the curricula stipulations.

For the most part, women feature in the textbooks to illustrate "oral tradition", "cultural heritage", and kinship relations. As per the colonial period, women are mainly associated with working in the fields or trading with local raw materials. In many cases, the images presented are in line with a colonial visuality, thus setting up a mode of representation that contributes to women's objectification.

We observed few references to the role of women in the history of Africa, in general, and in the history of Mozambique, in particular. Resistance to colonialism is mainly told in male terms, as are the liberation struggles, neglecting the literature highlighting women's agency and role in nation-building (cf., Casimiro, 2004; Meneses, 2017; Zimba, 2012). Many other relevant data could be cited to account for women's participation in resistance and liberation struggles and the struggle for peace and beyond. Thus, it is not the lack of information on women or their images that justifies their absence in the textbooks.

In the textbooks analysed, the erasure of women is the norm, particularly prevalent in those by Texto Editores, where not a single woman portrayed is named. In Plural Editores' textbooks, there is an attempt to include women as historical agents. However, this work still falls short of the desirable due to the scarcity of women referred to as historical personalities, with name, face and role, and how the images selected in the textbook still configure gender stereotypes. That is not exclusive to the textbooks analysed. These conform to the dominant standard of public memory in Mozambique and beyond, which continues to be deeply androcentric (Cabecinhas, 2018; Meneses, 2017; Pereira, 2021).

So, as observed in recent studies of other countries (e.g., Chiponda & Wassermann, 2015; Fardon & Schoeman, 2010), the textbooks analysed keep on silencing and excluding women, as they are absent or portrayed as mere generic and non-personalised illustrations. The various educational agents need to produce significant work to combat gender inequalities, which continue to determine that the country's history is told as a "single story", strongly androcentric. A more plural narrative of the various histories to be told is essential to promote equal opportunities between men and women. Moreover, it is also vital to fight other inequalities in a country where history is still written almost exclusively from the South, tending to ignore other regions' historical personalities and different ethnolinguistic groups.

In a recent paper, Meneses (2017, p. 50) raises the following question: "which stories remain forgotten in the Mozambican narrative script?". While analysing the official history of the Mozambican nation, Meneses (2017) highlights the importance of "'opening' history to debate", considering that the work of "democratisation of history is an essential condition to broaden any cognitive justice claim" (p. 50). According to the author, "re-establishing the role of women in the recent history of Mozambique is one of the great challenges still confronting the liberation from patriarchal oppression, one of the main objectives of the national struggle" (Meneses, 2017, p. 51). That means that an active effort is needed to take the pulse and listen carefully to the plurality of voices towards greater social justice.

The emergence of feminist movements and gender studies revolutionised the field of social sciences by denouncing the silencing of women's contribution in contemporary political processes (Hayes, 2005; Santos & Amâncio, 2016). The fight against androcentrism in the public sphere requires various approaches, but it necessarily includes providing quality education for all children, regardless of their gender, ethnicity and social background. As far as textbooks are concerned, it is not enough to include images of women. It is essential to introduce them as persons and historical agents, not only as representatives of a homogeneous social category, of which nothing is expected beyond biological and cultural reproduction. As Meneses (2017) points out, "it is not only about adding or inserting women in History but questioning and challenging the very idea of 'official' history and problematising the dichotomy between the personal and the political" (p. 75).

In constructing a more plural history, oral narratives and various art forms play a decisive role. Cross-referencing written sources from different origins is also crucial so that "transnational" archives can play a decisive role in a scenario where "national" archives tend to be inaccessible to those who do not live in the country's capital. The unavailability of particular photographs can be overcome with drawings and other illustrations, bringing personalities who have been erased from history into the public sphere. When we state that it is vital to bring the contribution of women as historical agents into the public sphere, we mean that it is not enough to provide the illustration and the name. It is crucial to provide context for their historical action, allowing it to be discussed in its complexity, especially when discussing the 11th and 12th-grade textbooks. Nevertheless, in reality, for many Mozambican children and young people, the textbooks remain a "mirage", and sometimes the teachers' role is limited to dictating the textbooks in the classroom9.

In a recent text, José Castiano (2019) provided a pertinent reflection on education in Mozambique:

to the despair of most Mozambicans, namely parents and especially teachers, Mozambican education has been attacked by interests, alien to its very essence: it has gradually become a private forum. For lack of resources, the Government is penalising those who should be its allies: teachers. Despite alleged "innovations", teachers become the champions of suffering and poverty due to increasing impoverishment and deteriorating working conditions. (p. 278)

Understanding how the textbooks' content is handled in the classroom can make all the difference regarding the proposed activities and the conditions given (or not) to teachers to provide participatory and inclusive educational experiences. According to Castiano (2019),

the experience of wars (the liberation, the 16-year, the hostilities) with some periods of so-called "truce" ( ... ) showed Mozambicans a reality that we as a collectivity stubbornly refused to acknowledge: that our diversity should be put on the same level as nationalist unity. Thus, education should be as much on territorial and patriotic unity as on diverse and different. The war experience brought back the many colours which make up our historicity and Mozambican society today. This fundamental "discovery" that Mozambican society is making represents the discovery of "new and different communities" of Mozambique, which dispute their space of participation and articulate towards their inclusion in the areas of the economy, politics, culture, religiosities, power, gender and age. (p. 278)

We know that the construction of history is a form of exercising power. Generally, textbooks, as other instruments of public memory, mirror the power inequalities that structure the society, namely the asymmetries of symbolic power between men and women, relegating women to the fringes of invisibility. Gender issues, due to their complexity, are particularly challenging in a multicultural and multilingual country such as Mozambique, so accounting for the country's diversity in textbooks is particularly defiant. However, the exercise of decentralising and actively listening to other voices, especially those that have systematically been erased, is an essential contribution to promoting social inclusion, justice and peace.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable contributions as well as to all the persons and institutions whose collaboration was essential to this work. This article was developed in the context of the project Memories, Cultures and Identities: How the Past Weighs on the Present-Day Intercultural Relations in Mozambique and Portugal?, supported by Aga Khan Development Network and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (No. 333162622). This work is also supported by national funds through the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDB/00736/2020.

REFERENCES

Basílio, G. (2012). O currículo local nas escolas moçambicanas: Estratégias epistemológicas e metodológicas de construção de saberes locais. Educação & Fronteiras, 2(5), 79-97.https://ojs.ufgd.edu.br/index.php/educacao/article/view/2149 [ Links ]

Cabaço, J. (2007). Moçambique: Identidades, colonialismo e libertação (Tese de doutoramento, Universidade de São Paulo). Biblioteca Digital USP.https://doi.org/10.11606/T.8.2007.tde-05122007-151059 [ Links ]

Cabecinhas, R. (2018). Quem quer ser apagada? Memória coletiva e assimetria simbólica. In J. M. Oliveira & C. Nogueira (Eds.), Lígia Amâncio: O género como ação sobre o mundo (pp. 113-132). CIS-IUL. [ Links ]

Cabecinhas, R., Jamal, C., Sá, A., & Macedo, I. (2021). Colonialism and liberation struggle in Mozambican history textbooks: A diachronic analysis. In I. Brescó & F. van Alphen (Eds.), Reproducing, rethinking, resisting national narratives. A sociocultural approach to schematic narrative templates (pp. 37-57). Information Age Publishing [ Links ]

Cabecinhas, R., Macedo, I., Jamal, C., & Sá, A. (2018). Representations of European colonialism, African resistance and liberation struggles in Mozambican history curricula and textbooks. In K. van Nieuwenhuyse & J. P. Valentim (Eds.), The colonial past in history textbooks. Historical and social psychological perspectives (pp. 217-237). Information Age Publishing [ Links ]

Cabecinhas, R., & Mapera, M. (2020). Decolonising images? The liberation script in Mozambican History textbooks. Yesterday and Today, 24, 1-27.https://doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2020/n24a1 [ Links ]

Cajani, L., Lässig, S., & Repoussi, M. (Eds.). (2019). The Palgrave handbook of conflict and history education in the post-Cold War era. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Carretero, M., Berger, S., & Grever, M. (Eds.). (2017). Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Casimiro, I. (2004). Paz na terra, guerra em casa: Feminismo e organização de mulher em Moçambique. Promédia. [ Links ]

Castiano, J. P. (2019). Os tempos da educação em Moçambique. In J. P. Castiano, R. Raboco, D. P. Pereira, S. Muianga, & M. J. Morais (Eds.), Moçambique neoliberal. Perspectivas críticas teóricas e da práxis (pp. 275-279). Editora Educar; Ethale Publishing. [ Links ]

Chiponda, A., & Wassermann, J. (2015). An analysis of the visual portrayal of women in junior secondary Malawian school history textbooks. Yesterday & Today, 14, 208-237.https://doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2015/nl4a9 [ Links ]

Coelho, J. P. B. (2013). Politics and contemporary history in Mozambique: A set of epistemological notes. Kronos, 39(1), 20-31. [ Links ]

Costa, A. (2019, 4 de março). Bertina ou a arte de Bertina: Mudar e permanecer. Buala.https://www.buala.org/pt/cara-a-cara/bertina-ou-a-arte-de-bertina-mudar-e-permanecer-0 [ Links ]

Costa, A. (2020, 27 de fevereiro). Reinata Sadimba. Buala.https://www.buala.org/pt/cara-a-cara/reinata-sadimba [ Links ]

Fardon, J., & Schoeman, S. (2010). A feminist post-structuralist analysis of an exemplar South African school history text. South African Journal of Education, 30(2), 307-323.https://doi.org/10.15700/SAJE.V30N2A333 [ Links ]

Hayes, P. (2005). Introduction: Visual genders. Gender & History, 17(3), 519-537. [ Links ]

Ide, T., Kirchheimer, J., & Bentrovato, D. (2018). School textbooks, peace and conflict: An introduction. Global Change, Peace & Security, 30(3), 287-294.https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2018.1505717 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação. (2010 a). História, programa da 11ª classe. Diname. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação. (2010b). História, programa da 12ª classe. Diname. [ Links ]

Jamal, C. M. (2019). Representações do colonialismo nos manuais escolares de História do 1º ciclo do ensino secundário geral no período pós-independência em Moçambique Tese de doutoramento, Universidade do Minho) . RepositóriUM. http://hdl.handle.net/1822/66902 [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1991). Mémoire de masse: Le côté moral et affectif de l’histoire. Bulletin de psychologie, 45, 239-256. [ Links ]

Khan, S., Meneses, M. P., & Bertelsen, B. (Eds.). (2019). Mozambique on the move. Challenges and reflections. AEGIS. [ Links ]

Laisse, S. (2020). Letras e palavras: Convivência entre culturas na literatura moçambicana. Escolar Editora. [ Links ]

Lei n.º 4/83, de 23 de março, Boletim da República, I Série- Número 2. (1983). [ Links ]

Lei n.º 6/92, de 6 de maio, Boletim da República, I Série - Número 19. (1992). [ Links ]

Lorenz, C. (2017). ‘The times they are a-changin’. On time, space and periodization in history. In M. Carretero, S. Berger, & M. Grever (Eds.), Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education (pp.109-132). Palgrave Macmillan.https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52908-4_6 [ Links ]

Machel, S. (1973). A libertação da mulher é uma necessidade fundamental da revolução. Tempo, 287, 47-50. [ Links ]

Mazula, B. (1995). Educação, cultura e ideologia em Moçambique: 1975-1985. Afrontamento. [ Links ]

Meneses, M. P. (2017). Autodeterminação em Moçambique: Joana Semião, entre a história oficial e as memórias de luta. In I. Mata (Ed.), Discursos memoralistas africanos e a construção da história (pp. 49-78). Colibri. [ Links ]

Mignolo, W. D., & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Mueio, T. (2019). Abordagem do tema transversal género e equidade na disciplina de português, 10ª classe. In C. Maciel (Ed.), Educação em género (pp. 61-83). Centro de Estudos Interdisciplinares de Comunicação. [ Links ]

Ngomane, N. (2012, 6 de janeiro). Quem quer ser apagado? Sol, p. 24. [ Links ]

Nhapulo, J. (2019). História 12ª classe. Plural Editores. [ Links ]

Nhapulo, J., & Cumbe, G. (2015). História 11ª classe. Plural Editores. [ Links ]

Nora, P. (1989). Between memory and history. Les lieux de mémoire. Representations, 26, 7-24. [ Links ]

Pereira, A. C., Sales, M., & Cabecinhas, R. (2020). (In)visibilidades: Imagem e racismo. Vista, (6), 9-19.https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.3054 [ Links ]

Pereira, D. M. P. (2021). Joana Semião, homo economicus e homo politicus: Urdindo uma epistemologia “tolerante” moçambicana. Ex æquo, 43, 165-181.https://doi.org/10.22355/exaequo.2021.43.11 [ Links ]

Pollak, M. (1989). Memória, esquecimento, silêncio. Revista Estudos Históricos, 2(3), 3-15. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, F. (2015). Educação e ensino de história em contextos coloniais e pós-coloniais. Mneme - Revista de Humanidades, 16(36), 27-53. [ Links ]

Santos, H., & Amâncio, L. (2016). Gender inequalities in highly qualified professions: A social psychologic analysis. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 4(1), 427-443.https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v4i1.487 [ Links ]

Schefer, R. (2016). Mueda, memória e massacre, de Ruy Guerra, o projeto cinematográfico moçambicano e as formas culturais do Planalto de Mueda. Comunicação e Sociedade, 29, 53-77.https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.29(2016).2408 [ Links ]

Silva, C. (Ed.). (2013). Kulimando saberes: Viagens discursivas pela pedagogia, didática, comunicação, antropologia cultural, filosofia, espiritualidade, língua e literatura. Alcance Editores. [ Links ]

Vicente, F. (Ed.). (2014). O império da visão. Fotografia no contexto colonial português. Edições 70. [ Links ]

Vilhena, M. C. (1999). As mulheres do Gungunhana. Arquipélago História, 2(3), 407-416.http://hdl.handle.net/10400.3/289 [ Links ]

Voz da Revolução. (1972). Voz da Revolução. Órgão oficial da Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO). Voz da Revolução, 14, 1-8. [ Links ]

Wertsch, J. V. (2002). Voices of collective remembering. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Zimba, B. (Ed.). (2012). A mulher moçambicana na luta de libertação nacional: Memórias do destacamento feminino (Vol. 1). Centro de Pesquisa da Luta de libertação Libertação Nacional; Ministério dos Combatentes. [ Links ]

Notes

1The Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO; Front for the Liberation of Mozambique), which began in 1962 as a movement fighting for national independence, was transformed into a political party in 1977. There is a convention in Mozambican historiography: "FRELIMO" in capital letters refers to the liberation movement while "Frelimo" in lower case letters refers to the governing state of independent Mozambique. In this text, we maintained the original style used in the cited sources.

2Both publishers belong to publishing groups based in Portugal, Grupo Porto Editora and Grupo Leya, respectively.

3When comparing this textbook with its previous edition (2010), we note that the wording is unchanged; however, the has been an update in the images. The new cover includes children (all male), and the chapter dividers are now full-page photographs. These photographs, featuring young men in different scenarios (urban and rural), are recent and seem to have been introduced to make the textbook more visually appealing (in the previous version, no images were used as chapter dividers). For this work, we conducted some interviews with textbook authors about the writing process and the choice of images. The persons we interviewed noted that the images featured in a particular textbook are not selected by the text authors, as they are dependent on availability and budget criteria. The photo labelling and captioning processes are also often handled by other persons. They also pointed out that, although the production of a textbook requires the involvement of experts in different areas (scientific, pedagogical, graphic aspects, etc.), the work is usually sequential, that is, they rarely have the opportunity to work as a team.

4On Reinata Sadimba's creative work and how it has been categorised, see, for example, Costa (2020).

5Leopoldo de Almeida's relief, part of the statue of Mouzinho de Albuquerque in the then Lourenço Marques, where there is now a statue of Samora Machel. The panel is now in the Nossa Senhora da Conceição Fortress, also known as Maputo Fortress.

6The Texto Editores' textbook (H12 História 12ª Classe, Mussa, 2015) refers to the last emperor of Gaza as Ngungunyane and the Plural Editores' textbook (História 12ª Classe, Nhapulo, 2019) as Gungunhana.

7Generally, the emperor and the persons deported with him to Lisbon are said to have died in exile in the Azores, but this is not true for women (see, for example, Vilhena, 1999).

8On the importance of Bertina Lopes' artistic production, for example, Costa (2019).

9On the importance of Bertina Lopes' artistic production, for example, Costa (2019).

Appendix: Textbooks Analysed

There are four textbooks under analysis, two for 11th-grade (História 11ª Classe, 11th-Grade History, 2015; H11 História 11ª Classe, H11 11th-Grade History, 2017) and two for 12th-grade (História 12ª Classe, 12th-Grade History, 2019; H12 História 12ª Classe, 12th-grade History, 2015).

Mussa, C. (2015). H12 história 12ª classe. Texto Editores.

Nhapulo, J. (2019). História 12ª classe. Plural Editores.

Nhapulo, J., & Cumbe, G. (2015). História 11ª classe. Plural Editores.

Sumbane, S. A. (2017). H11 história 11ª classe (2.ª ed.). Texto Editores.

Received: July 19, 2021; Revised: August 31, 2021; Accepted: September 01, 2021

texto em

texto em