Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

Share

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

On-line version ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.11 Braga June 2023 Epub July 30, 2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.4460

Varia

Between Cyberfeminism and Artivism: Feminism in Portugal on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women

i Instituto de Comunicação da NOVA, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

ii Centro de Investigação em Comunicação Aplicada, Cultura e Novas Tecnologias, Universidade Lusófona, Porto, Portugal

A modalidade visual é um recurso imprescindível para as ciberfeministas desde a sua origem. A união entre o artivismo e o movimento feminista visa descolonizar os saberes artísticos e exclusivistas, além de propiciar visibilidade às temáticas das mulheres, especialmente em relação às múltiplas formas de violência de género. Assim, este artigo tem como principal objetivo perceber de que forma as ciberfeministas recorreram ao artivismo feminista para assinalar o Dia Internacional para a Eliminação da Violência contra as Mulheres, em 2021, em Portugal. Recorrendo a análise de conteúdo, observamos as publicações do Instagram de 10 associações e coletivos feministas portugueses no dia 25 de novembro, separando os dados em intervenções online e offline, na constatação de que o ciberfeminismo articula fronteiras que interconectam esses espaços de forma permanente. Destacamos que o artivismo opera no atual movimento feminista português como uma ferramenta estratégica e política para disseminação e propagação do ciberfeminismo.

Palavras-chave: ciberfeminismo; artivismo; Instagram; violência de género; Dia Internacional para a Eliminação da Violência contra as Mulheres

Visual content has been a valuable resource since the creation of the cyberfeminist movement. Together, artivism and the feminist movement aim to decolonise artistic and exclusivist knowledge while also raising awareness of women's issues, especially concerning various forms of gender-based violence. Thus, the main aim of this article is to ascertain how cyberfeminists resorted to feminist artivism to celebrate the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in Portugal in 2021. To do so, Instagram posts by 10 Portuguese feminist organisations and collectives, posted on 25th November, were analysed through content analysis, and the data divided into online and offline measures - permanent proof of cyberfeminism as a border connecting these mediums. It is worth noting that artivism operates within the current Portuguese feminist movement as a strategic and political tool for the dispersal and propagation of cyberfeminism.

Keywords: cyberfeminism; artivism; Instagram; gender-based violence; International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women

1. Introduction

The International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women was established by the United Nations General Assembly in 1999, pursuant to resolution 52/134, in what was a clear tribute to “Las Mariposas”. On 25th November 1960, the Mirabal sisters, Patria, Maria Tereza and Minerva, were assassinated for opposing Rafael Trujillo’s dictatorial regime in the Dominican Republic, becoming symbols of popular resistance and the feminist movement itself.

Feminist activists have since celebrated this day as an opportunity to expose the gender inequalities in today's patriarchal society, which ultimately marginalises women and makes them hostages of a cycle of various forms of violence that continues to refute the public/private dichotomy.

Thus, gender-based violence can be understood to be discrimination and violence directed against a woman solely because she is a woman (Neves & Costa, 2017). Physical and sexual violence, harassment, dating and intimate partner violence that leads to homicide and femicide, to name a few, are serious human rights violations and should, indeed, be seen as a public health problem.

In Portugal, the occurrences of these forms of violence are high, with 25 women having been murdered in 2021, as noted by the Relatório Final 2021 (2021 Final Report; Dias et al., 2021) produced by the Observatory of Murdered Women of the União de Mulheres Alternativa e Resposta. According to the report, 595 women were killed between 2004 and 2021, which is an average of 33 deaths per year in the country. Several governmental measures have been implemented to tackle the issue, particularly by the Department of Gender Equality and Citizenship and the Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality. However, the notable efforts made by feminist organisations and collectives have been vital in combatting the many facets of gender-based violence, given their tireless work on the streets and in cyberspace.

Cyberfeminism, which originally questioned the role assigned to women and their relationship with information and communication technologies, has become a new force unto itself by allowing for and introducing previously silenced voices, as well as providing a stage for feminist principles thanks to the freedom of movement found in cyberspace (Lamartine & Cerqueira, 2022). As a result, non-hegemonic feminisms are able to gain greater visibility in a hybrid performance between collective and connected action (Babo, 2018).

Silenced voices also find both a means and place for expression in artivism

(Ribeiro, 2017). Artivism can be considered to be a combination of art and political activism (Kuperman, 2019), where marginalised groups break new developmental ground by employing art as a political strategy. In this sense, this paper shall seek to understand the way in which cyberfeminists turned to artivism to celebrate the 25th November and protest against gender-based violence in Portugal, considering that feminist artivism, by definition, must provide direct criticisms of the patriarchy as a mechanism of female subordination and domination (Biroli & Miguel, 2015).

As such, the content produced by the Instagram accounts of the following Portuguese feminist organisations and collectives, posted on the 25th November, was analysed, totalling 86 posts: A Coletiva, Associação Gravidez e Parto, Associação Plano I, Colagens Feministas, Feminismos Sobre Rodas, Feministas em Movimento, ILGA Portugal - Intervenção Lésbica, Gay, Bisexual, Trans e Intersex, Já Marchavas, Liga Feminista do Porto, and União de Mulheres Alternativa e Resposta.

Though they are based on similar underlying political affiliations, the intersection between artivism and cyberfeminism in the Portuguese setting lacks in-depth research. This article does not, however, intend to discuss art and its historical foundations, rather, it seeks to determine the extent to which cyberspace works as a facilitator of feminist and aesthetic experiences.

2. Gender-Based Violence(s): From Private to Public

Since the turn of the century, violence against women has been a significant topic on the political agendas of governmental institutions worldwide. As Oliveira (2019) states, this focus has been consolidated as a direct result of the work done by feminist movements, which have taken a leading role in the broad discussion of gender issues within the public agenda, disregarding barriers and borders and cemented in the use of theories as both an ethical and political commitement.

These feminist movements were silenced, weakened by the social context brought about by the dictatorship in Portugal, which began in 1926 - the "national dictatorship" transitioning to Salazarism, which ended in 1974 - having eventually brought the country to a standstill in terms of promoting gender issues when compared to other European countries (Tavares, 2011). Nevertheless, since the promulgation of the new Constitution of 1976 - once the dictatorship had ended - Portugal has been striving to overcome gender-based violence, as well as criminalising perpetrators of intimate partner violence, and thus intervening to ensure victims are protected.

Three years later, on 18th December 1979, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (Convenção Sobre a Eliminação de Todas as Formas de Discriminação Contra as Mulheres, 1979), also known as the International Bill of Women's

Rights, which was ratified in Portugal on 30th July 1980 and came into effect on 3rd September the following year.

Article 1 of the Convention determines what constitutes discrimination against women and therefore establishes a series of actions that can be taken to combat discrimination in order to speed up the gender equality process. Discrimination against women is:

any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field. (Convenção Sobre a Eliminação de Todas as Formas de Discriminação Contra as Mulheres, 1979, Art. 1)

This document is considered the first international human rights declaration that focuses specifically on issues concerning violence against women. According to Castilhos (2014), the document mentions that violence against women is, indeed, a degrading violation of human rights in terms of the fundamental aspect of freedom, but this is not explicitly presented, even though the phenomenon constitutes major discrimination.

If we appeal to the narrative of waves, it was during the second wave of the feminist movement that the public/private dichotomy was first propagated, arising from the slogan "the personal is political”. Having coined this slogan, Carol Hanisch’s main concern was to expose arbitrary and oppressive views of women, which restricted them to the domestic environment, away from the public and political sphere and the development of society (Lamartine, 2021; Silva, 2019).

The first official definition was only introduced in 1993, with the adoption of the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, which was a milestone in defining domestic violence in particular, as it was previously perceived - by law - as something private in nature. As such, this declaration comprises any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.

Two years later, in 1995, the "Fourth World Conference on Women", also known as the "Beijing Conference", was held. This declaration is seen by Cerqueira and Gomes (2017) as a turning point for gender equality discourse worldwide, especially in Portugal. The Beijing Platform for Action presents 12 key areas - one of which is violence against women - that are broken down into 52 goals in the form of over 600 measures.

In 2020, 25 years later, during the 64th session of the Commission on the Status of Women, Member States (Comissão Para a Cidadania e a Igualdade de Género, 2020), including Portugal, committed to strengthening and increasing measures and fully implementing the Beijing Declaration, taking into consideration that new challenges have since arisen and further action needs to be taken to secure the rights of all women.

The Folha Informativa: Violência de Género (Information Sheet: Gender-Based Violence) produced by the Portuguese Association for Victim Support (Associação Portuguesa de Apoio à Vítima, 2020) states that gender-based violence includes all forms of violence directed towards women because they are women and/or that affects them disproportionately and unequally, violating their physical and psychological integrity. Along the same lines, Sardenberg and Tavares (2016) add that violence can also be social or symbolic based on the way society is structured, to the detriment of gender as a direct product of the system, which is patriarchal and, therefore, discriminatory.

It was following the implementation of Article 153 of the Portuguese Penal Code in 1982 (Decreto-Lei n.º 48/95, 1995), which deems abuse as a crime punishable by law in Portugal, that many changes ensued, most notably the public policies that gained strength following the implementation of the First National Action Plan Against Domestic Violence (Lamartine, 2021). On 16th September 2009, Law no. 112/2009 (Lei n.º 112/2009, 2009) was legally established the framework for the prevention of domestic violence and victim protection (Bandeira & Magalhães, 2019), rendering it a public crime under Article 152 of the Portuguese Penal Code (Decreto-Lei n.º 48/95, 1995).

The Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (Convenção do Conselho da Europa Para a Prevenção e o Combate à Violência Contra as Mulheres e a Violência Doméstica, 2011), which was held in 2011, was ratified by the Portuguese Government two years later and came into effect in 2014, requiring member States that signed it to adjust their national legislation to protect women against all forms of violence, including intimate partner violence, forced marriage, mental and physical abuse, stalking, sexual violence (including rape), among others. This time, the notion of femicide was also listed in an attempt to ensure the social and political recognition of the sexist nature of these crimes (Bandeira & Magalhães, 2019).

In this Convention (Convenção do Conselho da Europa Para a Prevenção e o Combate à Violência Contra as Mulheres e a Violência Doméstica, 2011), also known as the “Istanbul Convention”, gender-based violence was defined as an act against any person based solely on their gender, motivated by beliefs, attitudes and gender roles in society, as it can happen to both women and men. However, there is an understanding that women are at greater risk of experiencing genderbased violence, as sociopolitical structures at legislative, institutional, cultural, and social levels favour male supremacy (Neves & Costa, 2017; Offen, 2008).

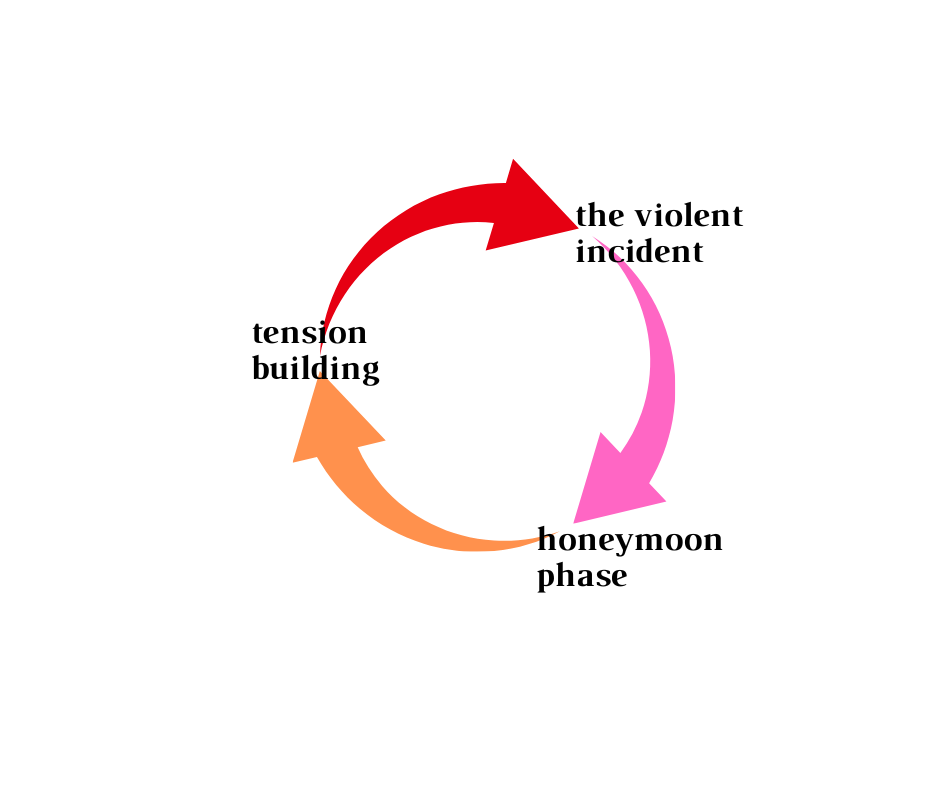

In this light, Walker (1999) suggests what he calls a “cycle of abuse”, divided into three stages that occur cyclically rather than in isolated acts, as shown in Figure 1. The idea is to try to justify, or at least comprehend, how women become victims and hostages of "battered woman syndrome". The first stage, “tension building”, refers to the pressures of daily life that start building up inside the abuser, producing a high feeling of danger in the victim. The second stage, “the violent incident”, as the name suggests, happens when the abuse finally occurs, whether at a physical and/or psychological level. The last stage of the cycle is the “honeymoon phase”, during which the abuser shows remorse and asks for forgiveness while promising to change their behaviour.

For Bandeira and Magalhães (2019), the premise of male supremacy allows women to be socially subordinated and submissive to men and is most likely the reason why they permanently bind themselves to this cycle of contempt, discrimination, and violence.

3. Artivism and Cyberfeminism: Feminism as Activism

The impact of the feminist movement on various social spheres is undeniable. For instance, journalists and the media itself - albeit in a tentative and incipient effort - have shown concern for reshaping their news coverage to make it even more diverse and inclusive (Magalhães et al., 2012); and advertisements are addressing issues of body positivity and femvertising (Drake, 2017). In the field of visual arts, feminism has led several artists to question gender-based violence and male dominance, especially in art, their voices coming together behind the need for an approach that is both political and social (Stubs et al., 2018).

As Kuperman (2019) mentions, artivism emerged in the late 1960s from the fusion of political activism and conceptual art to raise public awareness - the Vietnam War was taking place at the time - through several different language forms, which may even complement each other. Centella (2015) also points out that artivism derives from the union between art and the desire for social change based on our collective conscience, thus allowing people who have been silenced to have their voices heard.

For researcher Paulo Raposo (2015), artivism is a modern concept that still lacks consensus in the fields of arts and social science, it

draws on connections, which are classic but also prolix and controversial, between art and politics, stimulating potential endings for art as an act of resistance and subversion. It can be found in social and political interventions carried out by individuals or collectives through poetic and performative strategies. ( ... ) Its aesthetic and symbolic nature broadens, raises awareness, reflects on and discusses themes and situations in a given historical and social context, aiming at change or resistance. Artivism is thus established as a cause and social claim as well as an artistic rupture - namely, by proposing scenarios, landscapes and alternative ecologies of fruition, engagement and artistic creation. (p. 5)

In addition, Machado (2019) explains that protests of collective interest spread by artivism are susceptible to civil disobedience as a legitimate tool of vindication since “its modus operandi can be defined by the experimental nature of the compositional procedures employed in the interventions, grounded in a circle that brings together the notions of 'idea', 'ideal' and 'fight'” (p. 54).

Mesquita (2011) further emphasises that activist art is not merely art. It is also political, implying a direct approach towards engagement in productions and their forces outside of official and traditional mediations, that is, through different, alternative technologies and media; artivism aims to critically intervene in society by means of artistic actions without, however, requiring the erudition of conceptual art (Costa & Coelho, 2018).

The late 1960s also marked the rise of feminist artivism, highlighting the aforementioned message "the personal is political", exploring the female body, femininity, and female sexuality (Kuperman, 2019), which according to Flávia Biroli and Miguel (2015), characterises this form of artivism, meaning that content should always be rooted and linked to criticism of the patriarchal system as a tool for the subordination and domination of women.

Costa and Coelho (2018) identify different branches of feminist artivism. One is the essentialist perspective, which is guided by particular biological traits that determine what constitutes femininity. Another is the constructivist idea, which is grounded in the belief that gender is a social construction. Then there is the intersectional branch that is based on Kimberlé Crenshaw's definition of intersectionality, which seeks to conciliate layers of oppression (Cerqueira & Magalhães, 2017).

This union between artivism and feminist critique is seen by Lessa (2015) as bringing about the democratisation of access to information in its appropriation of public space. In other words, artivism attempts to decolonise art by making it more accessible to different audiences - regardless of their social and financial status - and by not confining art to museums and galleries, as is the norm, but using it as a symbol in the streets, transgressively, while also recognising that women, whether artists or not, may use visual content as a means of political and social intervention founded in critical thinking and acknowledgement (Costa & Coelho, 2018) - a notion that has gained greater visibility and reach with the development of cyberspace.

The rise of the internet made it possible for communication to transcend hegemonic media and become more hierarchical and democratic, allowing the feminist movement to increase the reach and spread of debates among women (Cerqueira, 2015; Fernández et al., 2019; Lamartine, 2021). The feminist movement soon realised the potential of digital social media as a means through which to propagate its ideals, questioning gender inequalities and the roles attributed to women in the fields of science and technology and electronic culture, which went on to establish cyberfeminism (Martinez, 2015).

The conceptualisation of cyberfeminism is commonly credited to philosopher Sadie Plant, who discussed the relationship between women and new technologies as an emancipatory tool, as well as Australian feminist group VNS (VeNuS)

Matrix, following the publication of the Cyberfeminist Manifesto in homage to Donna Haraway's work (1995) and her cyborg body manifesto.

Historically, cyberfeminism was born as a set of political-aesthetic actions that included handing out posters and zines from a more analogue perspective, as well as digital manifestos, computer games, codes, billboards, events, performances, and art exhibitions, always with the aim of emphasising differences when compared to the androcentrism promoted by 1980s cyberpunk art (Reis & Natansohn, 2021, p. 52).

From then on, cyberfeminism began to take an interest in exploring not only the theoretical but also the artistic potentials of technologies, effectively bringing feminist activism into cyberspace (Sofoulis, 2002) in promoting the adaptation of technological tools and greater political coordination (Reis & Natansohn, 2021). Therefore, feminist artivism creates a new space of resilience and fight, breaking the boundaries of the digital world through digital social media and other platforms. It is, above all, the protagonist of protests against predominant social norms by means of creativity and new transgressive points of view (Lessa, 2015).

Feminist activism has been making use of the potential features of the digital sphere, of increased communication and interaction, which has spawned a new debate surrounding what several authors and activists refer to as the "fourth wave of the feminist movement", mainly characterised by the growth of social media and digital platforms (Cochrane, 2013; Parry et al., 2018; Silva, 2019). While a consensus is far from being reached, and the narrative around the waves of the feminist movement is subject to much criticism, this new wave focuses on social inclusion by exposing issues relating to the prejudices that affect identity, such as racism, LGBTphobia, ableism, ageism, and other forms of discrimination, calling for the need to give people a voice (Ribeiro, 2017).

For Diana Parry et al. (2018), the fourth wave can be defined by four main characteristics. First, there are blurred boundaries across waves, that is, undefined borders separating this wave. This is also pointed out by Kuperman (2019) regarding the topics addressed by artivism projects. The author states that the causes being claimed today have mostly remained the same since the 1960s and include sexual liberation, the legal right to abortion, and, especially, the multiple forms of gender-based violence. Another characteristic of the fourth wave pertains to technological mobilisations as an essential aspect within these feminist projects, which gave rise to movements such as #MeToo and #NiUnaMenos in a proliferation of heterogeneous feminist networks where the collective use of hashtags served as a point of convergence for processes and battles (Reis & Natansohn, 2021). Then, a rapid, multivocal response to sexual violence was identified, and “the way that these women mobilised others to fight against sexism in their community, igniting a larger global discussion on victim-blaming, shows the emancipatory potential of the fourth wave of feminist action” (Parry et al., 2018, p. 9). Finally, Parry et al. (2018) emphasise the interconnectedness brought about through globalisation, in which intersectional underpinnings are key to gender equality issues. Thus, it is clear that contemporary feminists increasingly seek to include representation in the feminist discourse on intersectionality (Cerqueira & Magalhães, 2017; Cochrane, 2013). This new stage in the feminist movement offers a new cycle of political overtures through cyberfeminism, driven by relatable links and the creation of bonds between women. Artivism, which is also a political medium, is a mechanism employed to raise awareness through the emotions evoked and empathy fostered by art (Kuperman, 2019; Lessa, 2015).

As such, new repertoires of action are also created. In Portugal, many transnational demonstrations are organised in a hybrid approach, similar to the International Women's Strike or the 8M Feminist Strike, which makes use of the possibilities provided by cyberspace and siezes the street as a symbolic space (Lamartine & Cerqueira, 2022). Or, even, public campaigns against a common cause, such as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, which has not only been supported by the Government under the Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality, but also by several feminist collectives all over the country.

4. Methodology

The main aim of this study is to understand how Portuguese feminist collectives celebrated the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in Cyberspace in 2021, and in particular, how cyberfeminists resorted to artivism and visual aspects on this day. As such, a content analysis of the Instagram posts of 10 organisations and collectives was carried out.

This platform was selected due to its reliance on visual content, having been initially conceived for photo sharing - and later extended to videos - as the intention herein is, above all, to assess aesthetic production. Moreover, as a platform, Instagram has been continuously on the rise, recording high quarterly figures in terms of both followers and advertising, with a growth of almost 60% over the past few years, according to data from DataReportal's (2022) Digital 2022 Global Overview Report.

Following an initial analysis of 23 well-known feminist organisations and collectives in Portugal, the posts selected are those that (a) were centered around the subject of feminism in Portugal and (b) were posted on 25th November 2021 specifically to mark the international day in question. Therefore, the corpus employed is made up of posts from Feministas em Movimento (@feministasemmovimento), Feminismos Sobre Rodas (@feminismossobrerodas), A Coletiva (@a_coletiva_feminismos), União de Mulheres Alternativa e Resposta (@umar_feminismos), ILGA (@ilgaportugal), Já Marchavas (@jamarchavas), Associação Gravidez e Parto (@apdmgp), Liga Feminista do Porto (@ligafeministadoporto), Colagens Feministas (@colagens_feministas_lisboa) and Associação Plano I ( @associacaoplanoi), totalling 86 posts.

It is necessary, however, to clarify that many of these posts form part of what is referred to on Instagram as a "carousel", that is, a set of images shared as a single post. Thus, each image has been considered and accounted for separately for this analysis, not only because of its visual content but also because the images differ in terms of the categories they fit into, even if presented together in the same "carousel".

Bardin (1997/2004) states that content analysis relates both to the meanings and signifiers of the categorical division of the items analysed. Accordingly, the data has been divided into two major categories and, from these, organised into subcategories, as the object in this type of analysis is allowed to speak for itself and thus outline parallel categories in the course of the observations conducted (Bardin, 1997/2004).

It is important to mention that the analysis undertaken focuses not on the aesthetic discussion of the content but on the scope of feminist artivism, which, as Costa and Coelho (2018) remind us, can be practised by women. These women don't necessarily have to be artists, as long as they "use artistic methods to create and conduct political manifestatations of criticisms of the subordination of women in the patriarchal system" (p. 33).

The first category concerns aesthetic activities within cyberspace. Named "online interventions", this category is made up of 42 posts and is divided into four subcategories: "women are always the victims", "data and numbers", "posters” and

“LGBT women". The second category is called "urban interventions" and includes 44 posts divided into two subcategories: "feminist art" and "demonstration".

5. Online Interventions: Online Feminist Aesthetics

Cyberfeminism has brought women together on a glocal level - across the globe and in particular contexts of action. In Portugal, digital feminist activism connects north and south, mainland and islands, in activities organised by organisations and collectives and their various groups. As Reis and Natansohn (2021) point out, as activism shifts from communities of affinity to timelines, fostering daily engagement, it creates a routine of information and knowledge about the many issues faced by women.

For Abreu (2017), cyberspace acts as a bridge across which feminist artivism is able to deconstruct ever normalised power and knowledge relations, segregating, while also making room for the practice of a collective agency that is, in fact, critical of the various cultural constructions, questioning the invisibility and silence of women, stigmas and stereotypes that cause ruptures that open up “escape routes and interruptions in hegemonic narratives” (p. 148). In this sense, this category is made up of cyberfeminist actions published in a digital celebration of the 25th November, and is divided into three subcategories that include information, explanations, notices of meetings, and data on genderbased violence in Portugal. It should be noted that all images presented were considered to foster an appealling aesthetic, either thanks to their colour, font, or the illustration/photo used.

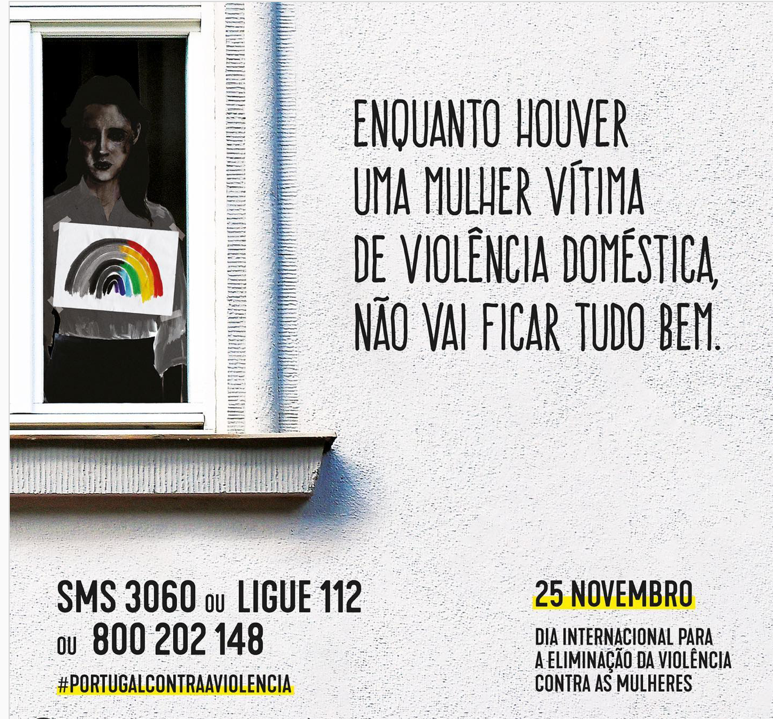

5.1. Women Are Always the Victims

Posts that portrayed women as victims were grouped under the subcategory "women are always the victims". Five posts stood out due to their representation of women bearing signs of physical violence, as shown in Figure 2. This type of context is quite common when dealing with violence against women, as the interpretation of this art in media discourse is always conditioned to a male perspective, which ends up building ideologies and stereotypes grounded in victimisation (Cerqueira, 2008; Cerqueira & Gomes, 2017), especially where domestic violence is concerned.

From Campanha #PortugalContraAViolência [Photo], by FEM - Feministas em Movimento [@feministasemmovimento], 2021, Instagram. (https://www.instagram.com/p/CWsYjAps7La/)

Figure 2 Instagram post @feministasemmovimento

Rendering women “poor little things” (Cerqueira, 2008) strengthens the propagation of a discourse that ends up typifying rather than faithfully representing the social condition of women, sustaining the patriarchal and dominating culture that is typical of Portuguese society (Bandeira & Magalhães, 2019). Thus, the public/private dichotomy is overcome by the limitations and sequels that this type of discourse delivers, remaining faithful to the binary premise that reconstructs a permissive political agency to the oppression and exploitation of women (Magalhães et al., 2012).

It can also be said that dark colours predominate, especially black when linked to victims, as illustrated in Figure 3. For Heller (2000/2014), black turns all positive meanings into negative ones, that is, it symbolises violence, death, pain, and the end. Gender-based violence is also represented by the colour black as a form of mourning and grief.

From @umar_feminismos @rede8marcoporto [Photo], by Feminismos Sobre Rodas [@feminismossobrerodas], 2021, Instagram. (https://www.instagram.com/p/CWsNg-aMh8l/)

Figure 3 Instagram post @feminismossobrerodas

The colour black is further associated with denial and contempt (Heller, 2000/2014), which are characteristics of the cycle of violence outlined by Walker (1999), one that keeps women oppressed under the alternatives available and stagnates them in the place of subjection, which undergoes continual social validation by male supremacy (Bandeira & Magalhães, 2019).

According to Tavares (2008), most artivist works adhere to the definition presented of this category, which is to say, to the debate surrounding the representation of the female figure, which is, most often, endowed with stereotypes, undermining and even humiliation, denouncing and protesting against the chauvinistic culture and places in which women are subordinated.

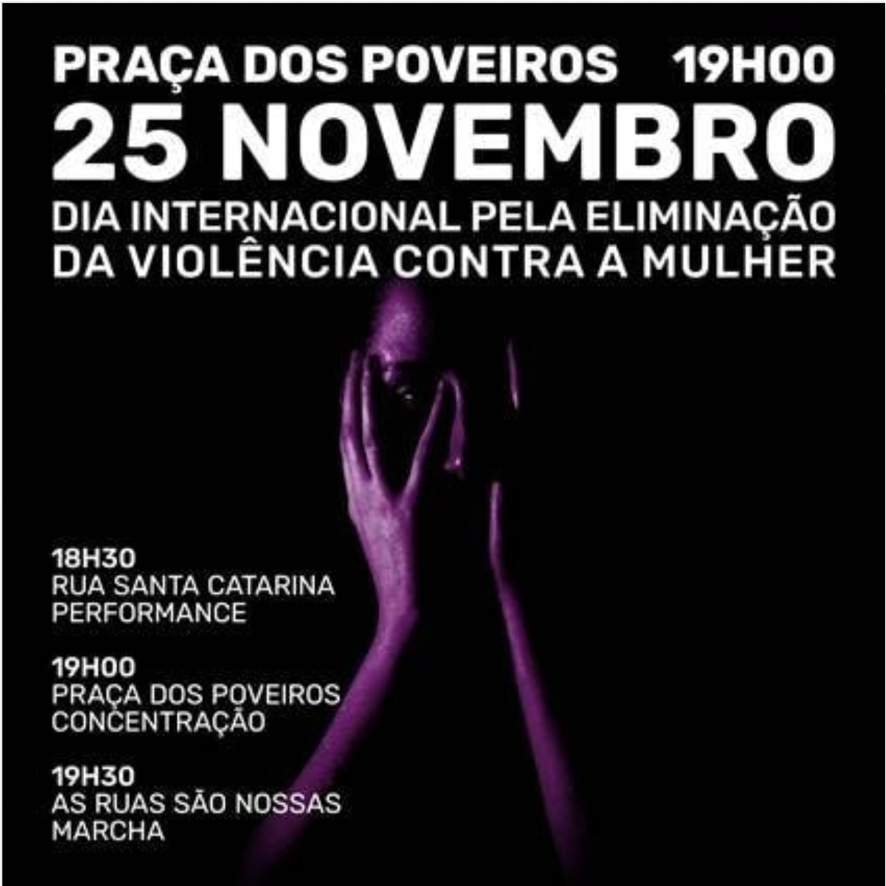

5.2. Data and Numbers

"Data and numbers" is the biggest subcategory, made up of 27 posts. This section contains posts that present explanations of the celebration of the 25th November: statistical data on gender-based violence in Portugal, and infographics (Figure 4). These posts corroborate what Kuperman (2019) understands as the decolonisation of information, meaning that there is a democratisation of access to this information beyond the printed pages of major newspapers and academia itself.

From Segundo o Observatório de Mulheres Assassinadas da UMAR, entre 1 Janeiro e 15 de Novembro de 2021 foram assassinadas 23 mulheres em Portugal [Photo], by UMAR ::: Associação Feminista [@umar_feminismos], 2021, Instagram. (https://www.instagram.com/p/CWqvhxCMOGa/)

Figure 4 Instagram post @umar_feminismos

The way in which the content is transmitted attempts not only to draw attention to the high rate of gender-based violence in the country and protest against it, but also, as Reis and Natanshon (2021) state, to make the internet accessible to everyone by means of a more easily understood language, thus helping make it a common resource.

Costa and Coelho (2018) support this by characterising protest art when there is the possibility of individual authorship, even if they are neither an artist nor a professional; they address everyday topics in the public space and become popular outside conventional spaces, including the media, as seen in the example analysed.

It is worth noting that, in addition to domestic violence and femicide - which are key issues - obstetric violence has made a significant appearance in the posts analysed, with interventions and omissions regarding prepartum, childbirth, and postpartum care as the main forms of violence. This is one of the most recent topics on the feminist activism agenda and has been publicly acknowledged in Portugal.

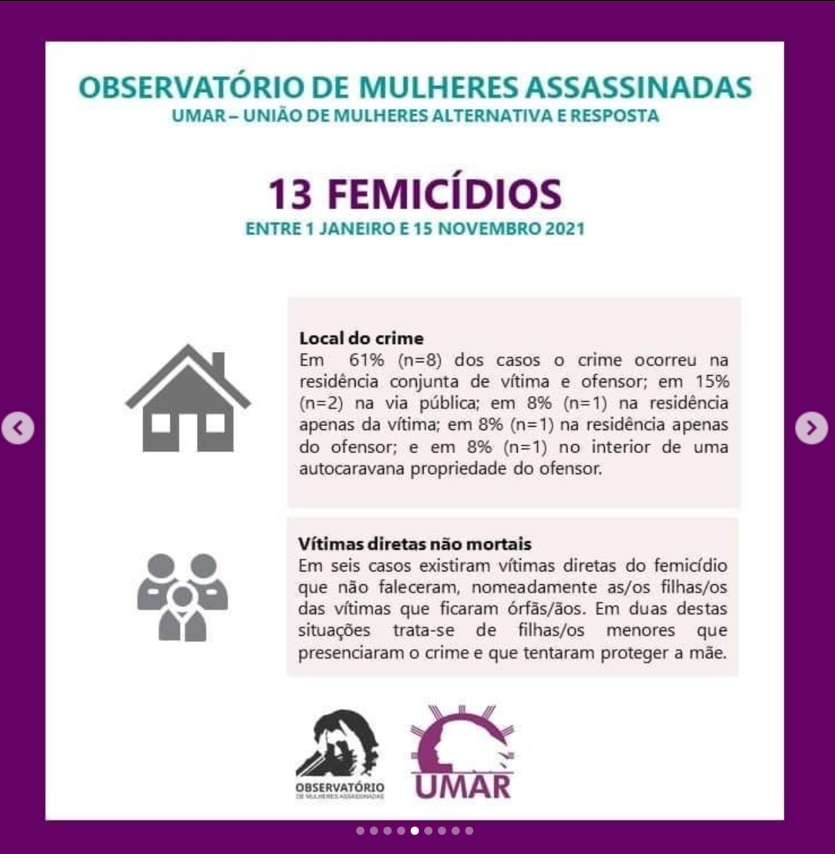

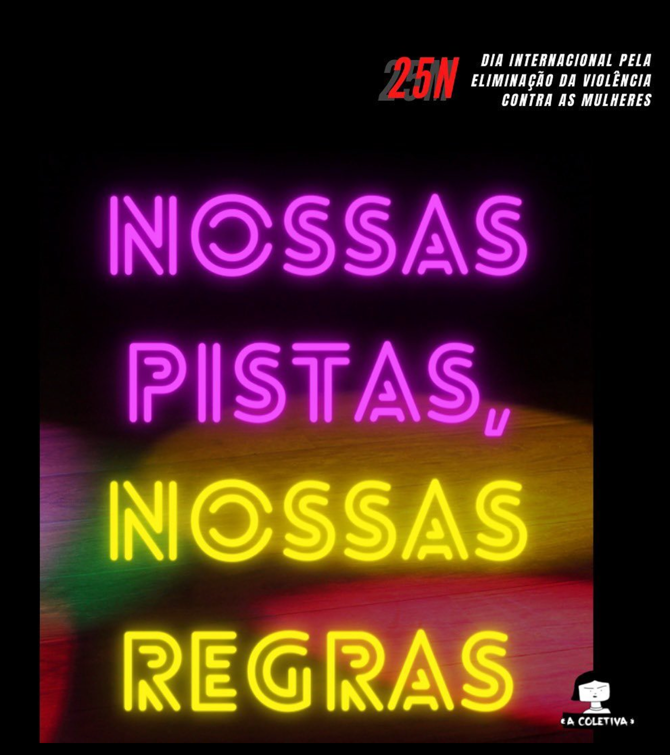

5.3. Posters

The subcategory "posters" grouped posts that focused more on words than images but which take on strong visual positioning. These contain catchphrases (Figure 5) and call for street demonstrations in a total of seven posts. Lessa (2015) states that language is an instrument of rupture with control and standardisation introduced to different bodies, as to politicise words is to open new possibilities of interpretation and transgression.

From Nesse 25/11, convocamos os bares de Portugal a apoiar uma noite livre de assédios! [Photo], by A C O L E T I V A [@a_coletiva_feminismos], 2021, Instagram. (https://www.instagram.com/p/CWtYUH3MeeH/)

Figure 5 Instagram post @a_coletiva_feminismos

The image shows words in capital letters and extremely bright colours reminiscent of nightclub neon lights, which is further supported by the use of the term “dance floors”. The idea presented resembles the various campaigns against harassment, especially along the lines of “my body, my rules”, which always makes an appearance amidst the “disorderly” words of feminist demonstrations in Portugal (Lamartine & Cerqueira, 2022).

This form of action reflects, as Parry et al. (2018) put it, the emancipatory power of the fourth wave of feminism and of cyberfeminism itself in the way that women join forces and rally to confront sexism, producing a glocal discussion around what Cochrane (2013) refers to as “rape culture”.

5.4. LGBT Women

The subcategory “LGBT women” featured the lowest number of posts, with only three images, and included posts that contained references to the LGBT community (Figure 6). For Stubs et al. (2018), this type of artivism deconstructs normative standards and stereotypes, promoting body diversity while raising a debate on gendered bodies, desexualised models and gender (Lessa, 2015).

From Dia 25 de novembro - Dia Internacional de Eliminação de Todas as Formas de Violência Contra Todas as Mulheres [Photo], by ILGA Portugal [@ilgaportugal], 2021, Instagram. (https://www.instagram.com/p/CWtZ9LTNvFf/)

Figure 6 Instagram post @ilgaportugal

The consolidation of intersectionality as a founding pillar of the fourth wave ensures greater plurality and representation (Cochrane, 2013; Lamartine & Cerqueira, 2022) with the inclusion of identities and symbols, as shown in the figure above. In this context, hegemonic feminism becomes a target of criticism for the segregation of other identity representations, calling for the urgent inclusion of non-normative individuals who have historically been rendered invisible or marginalised, even when at the heart of the feminist movement.

Since the emergence of cyberfeminism and artivism itself, the quest to break the gender binary system has galvanised into resistance, in an attempt to foreground different types of female bodies, yielding “hybrid subjectivities that engage with the world to create existential awareness and perspectives” (Stubs et al., 2018, p. 13).

6. Street Interventions: Offline Feminist Aesthetics

In a previous study, it was verified that the feminist movement taking over the streets is, above all, a symbolic practice (Lamartine & Cerqueira, 2022). As such, this category gathers posts that feature interventions in public spaces on 25th November 2021 in Portugal, although the COVID-19 pandemic was still producing mild effects on the country.

There are, in total, 44 posts that have been divided into two subcategories. Each one is composed of an identical number of posts, that is, 22 images each.

6.1. Feminist Art

As Kuperman (2019) voices, art is employed as a political strategy used by different marginalised groups to share their narratives and discourses, the purpose of which is to create and open up new fields of action and further development. Dissident discourses reached a larger audience and higher relevance due to artivist strategies of subversion, especially before the globalisation of the internet. These are disruptive visual expressions that surface in public spaces (Bogalheiro et al., 2021).

This subcategory presents street artivism, transgressive art, and politicised words, with special emphasis on the terms "fight" and "grief" (Figure 7; Lessa, 2015), emphasising the indissociable element that Stubs et al. (2018) deem to be a link between art and life, experience and the creation of subjectivity.

From A Liga Feminista do Porto surge em Maio de 2020, derivado da necessidade de ocupar um espaço de organização e mobilização das mulheres no Porto, pela reivindicação e luta contra a opressão patriarcal e os seus contornos de violência machista [ Photo], by Liga Feminista do Porto [@ligafeministadoporto], 2021, Instagram. (https://www.instagram.com/p/CWrYbIGoyS8/)

Figure 7 Instagram post @ligafeministadoporto

The image chosen and colours used reinforce the idea of resistance, given that the woman is wearing black, which, as previously mentioned, symbolises mourning, violence, and fear, and is holding a flag painted red, which is the colour of strength and courage, but also of aggressiveness and excitement (Heller, 2000/2014). Moreover, the phrase alerts us to the social system that excludes women from society, which is why, as Sardenberg and Tavares (2016) elaborate, genderbased violence is a product of social organisation or, in this particular case, the patriarchy.

The image also reflects what Machado (2019) understands to be artivism. It intervenes while taking into account its engagement, based on the indissoluble and inseparable triad of ideal, idea, and fight, which acts as a legitimate vindication and tool of protest.

Another intervention that illustrates the artivism that fosters social change and, according to Centella (2015), stems from collective awareness and unity is the one depicted in Figure 8. Artivists created a large patchwork quilt, sewed pieces of cloth together, and wrote the name of the women murdered in Portugal, up until that day, on each one. The oeuvre contained a total of 23 names written on pieces of cloth stitched together and laid out in a town square in the district of Viseu.

From #jamarchavas #jamarchavas2021 #viseu #25novembro #25n #feminismo [Photo], by Plataforma Já Marchavas! [@jamarchavas], 2021, Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/p/CWtmP3FgD3O/)

Figure 8 Instagram post @jamarchavas

For Lessa (2015), the use of a patchwork quilt provides important, commonly used imagery at the intersection between art and feminism. She also believes that there is a debate on the status of the object in art and on the distance between art and handicrafts, as the latter has historically been considered to be compulsory for women.

6.2. Demonstration

According to Reis and Natanshon (2021), the 21st century has seen the emergence of mass mobilisations with increased aesthetic, discursive, and multicentric inclusion. This subcategory includes images featuring collective street protests, such as women with banners (Figure 9), meetings, and gatherings, thus reflecting body and identity diversity, which is characteristic of the fourth wave of the feminist movement (Parry et al., 2018).

From Hoje, a 25 de novembro, marchámos juntas pelo fim da violência contra as mulheres. Que bonito e inspirador ver tantas ONGs juntas, com temas diferentes mas um denominador comum: a violência de género. Nas suas várias facetas e disfarces [Photo], by Associação Gravidez e Parto [@apdmgp], 2021, Instagram. (https://www.instagram.com/p/CWt4Z-5MQ8P/)

Figure 9 Instagram post @apdmgp

It is important to mention that these demonstrations were previously called for by the feminist organisations and collectives analysed, showcasing the power of cyberfeminism to articulate borders beyond geographical areas in the formulation of structures capable of permanently connecting online and offline spaces (Fernández et al., 2019). Therefore, the mitigation between collective action and connected action is discerned within the coexistence of communication and activism itself (Babo, 2018; Lamartine & Cerqueira, 2022).

7. Conclusion

The interaction between cyberfeminism and artivism provides insight into the different speaking spaces that are still marginalised and the subtleties of patriarchal oppression that undermine dissident identity representations and cover up gender-based violence. The art used as activism by cyberfeminists mirrors a concern for inclusion, protest, and a rupture that converts grieving into fighting and thus recentralises it within the scope of individual and collective action.

The findings of this study have shown that artivism has been used and resorted to by Portuguese organisations and collectives as a political and strategic tool for the propagation and promotion of cyberfeminism. Although no intention was made to discuss the boundaries of what is considered art, visual content has been widely adopted as a visibility strategy for the social and political feminist movement, both on the streets and in the digital space.

The online/offline dichotomy has shown a predilection for practices that take place outside cyberspace, which is why the category “street interventions” comprised the highest number of posts, including those relating to protests and urban art. This is an interesting factor that should be further analysed in future studies in order not only to understand the connections but also the differences regarding visual expression in digital media and on the streets.

The social configuration that cyberspace provides calls for attention to be paid to intersectionality, especially in the unfolding of the fourthwave of feminism, which can be verified by the inclusion of the LGBT community. However, it should be noted that inclusion was only possible for Portuguese collectives that are also active in the LGBTQIA+ movement, so it becomes necessary to rethink mainstream feminism in Portugal and its hegemonies in terms of white-heterocis-normativity. In other words, it is necessary to pay attention to what is made visible and what and who continues to be silenced in the bosom of feminist activism.

Cyberfeminism has thus established itself as an unprecedented force in challenging and vindicating the role of women and the fight against gender-based violence in and out of cyberspace through collective and connected action that transcends glocal boundaries. Artivism also breaks down dominant and normative standards by means of emotional and visual expression through art and its performative, artistic, and subversive nature, bridging the gap separating women from the public space in a call for social change.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by National Funds provided via the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Foundation for Science and Technology) as part of projects Refª 2021.07485.BD and FEMglocal - Glocal Feminist Movements: Interactions and Contradictions (PTDC/COM-CSS/4049/2021).

REFERENCES

A C O L E T I V A[ @a_coletiva_feminismos]. (2021, 25 de novembro). Retirado de Nesse 25/11, convocamos os bares de Portugal a apoiar uma noite livre de assédios! [Fotografia]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWtYUH3MeeH/ [ Links ]

Abreu, C. (2017). Narrativas digifeministas: Arte, ativismo e posicionamentos políticos na internet. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa (Auto)biográfica, 2(4), 134-152. https://doi.org/10.31892/rbpab2525-426X.2017.v2.n4.p134-152 [ Links ]

Associação Portuguesa de Apoio à Vítima. (2020). Folha informativa: Violência de género. https://apav.pt/apav_v3/images/pdf/FI_VDG_2020.pdf [ Links ]

Babo, I. (2018). Redes, ativismo e mobilizações públicas. Ação coletiva e ação conectada. Estudos em Comunicação, 1(27), 219-244. http://ojs.labcomifp.ubi.pt/index.php/ec/article/view/481 [ Links ]

Bandeira, L. M., & Magalhães, M. J. (2019). A transversalidade dos crimes de feminicídio/femicídio no Brasil e em Portugal. Revista da Defensoria Pública do Distrito Federal, 1(1), 29-56. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2004). Análise de conteúdo (L. A. Reto & A. Pinheiro, Trad.; 3.ª ed.). Edições 70. (Trabalho original publicado em 1977) [ Links ]

Biroli, F., & Miguel, L. F. (2015). Feminismo e política: Uma introdução. Boitempo Editorial. [ Links ]

Bogalheiro, M., Babo, I., & Cardoso, J. S. (2021). Expressões visuais disruptivas no espaço público. CICANT; Edições Universitárias Lusófonas. [ Links ]

Castilhos, T. M. S. (2014). A violência de género nas redes sociais: A proteção das mulheres na perspetiva dos direitos humanos [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade de Salamanca]. Ediciones Universidad Salamanca. [ Links ]

Centella, V. O. (2015). El artivismo como acción estratégica de nuevas narrativas artistico-políticas. Calle 14, 10(15), 100-111. https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.c14.2015.1.a08 [ Links ]

Cerqueira, C. (2008). A imprensa e a perspectiva de género. Quando elas são notícia no Dia Internacional da Mulher. Observatorio (OBS*), 2(2), 139-164. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS222008101 [ Links ]

Cerqueira, C. (2015). As estratégias de comunicação das ONGs de cidadania, igualdade de género e/ou feministas: Interconexões entre media mainstream e media sociais. In G. Gonçalves & F. Lisboa (Eds.), Coleção relações públicas e comunicação organizacional - Dos fundamentos às práticas (pp. 45-62). Labcom. [ Links ]

Cerqueira, C. & Gomes, S. (2017). Violência de género nos media: Percurso, dilemas e desafios. In S. Neves & D. Costa (Eds.), Violências de género (pp. 217-238). ISCSP. [ Links ]

Cerqueira, C., & Magalhães, S. (2017). Ensaio sobre cegueiras: Cruzamentos intersecionais e (in)visibilidades nos media. Ex aequo, 35, 9-20. https://doi.org/10.22355/exaequo.2017.35.01 [ Links ]

Cochrane, K. (2013). All the rebel women: The rise of the fourth wave of feminism. Guadian Books. [ Links ]

Comissão Para a Cidadania e a Igualdade de Género. (2020, 10 de março). Estados Membros concordam em implementar integralmente a Declaração de Pequim sobre igualdade de género. https://www.cig.gov.pt/2020/03/estados-membrosconcordam-implementar-integralmente-declaracao-pequim-igualdade-genero/ [ Links ]

Convenção do Conselho da Europa para a Prevenção e o Combate à Violência contra as Mulheres e a Violência Doméstica, 11 de maio de 2011, https://www.cig.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/conv_ce.pdf [ Links ]

Convenção Sobre a Eliminação de Todas as Formas de Discriminação Contra as Mulheres, 18 de dezembro de 1979, https://www.unicef.org/brazil/convencaosobre-eliminacao-de-todas-formas-de-discriminacao-contra-mulheres [ Links ]

Costa, M. A. C. N., & Coelho, N. (2018). A(R)Tivismo feminista - Intersecções entre arte, política e feminismo. Confluências, 20(2), 25-49. https://doi.org/10.22409/conflu20i2.p547 [ Links ]

DataReportal. (2022, 26 de janeiro). Digital 2022: Global Overview report. The essential guide to the world’s connected behaviours [PowerPoint slides]. SlideShare. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report [ Links ]

Decreto-Lei n.º 48/95, Diário da República n.º 63/1995, Série I-A de 1995-03-15. (1995). https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/decreto-lei/48-1995-185720 [ Links ]

Dias, C. M., Iglesias, C., Pontedeira, C., Armada, F. C. de, Rodrigues, L., & Magalhães, M. J. (2021). Relatório final 2021 (1 de janeiro a 31 de dezembro de 2021). União de Mulheres Alternativa e Resposta. http://www.umarfeminismos.org/images/stories/oma/OMAUMAR_Relatório_2021.pdf [ Links ]

Drake, V. E. (2017). The impact of female empowerment in advertising (femvertising). Journal of Research in Marketing, 7(3), 593-599. [ Links ]

FEM - Feministas em Movimento [@feministasemmovimento]. (2021, 25 de novembro). Campanha #PortugalContraAViolência[Fotografia]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWsYjAps7La/ [ Links ]

Feminismos Sobre Rodas [@feminismossobrerodas]. (2021, 25 de novembro). @umar_feminismos @rede8marcoporto [Fotografia]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWsNg-aMh8l/ [ Links ]

Fernández, E., Castro-Martinez, A., & Valcarcel, A. (2019). Medios sociales y feminismo en la construcción de capital social: La red estatal de comunicadoras en España. Análisis: Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura, 61, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3247 [ Links ]

Heller, E. (2014). A psicologia das cores - Como as cores afetam a emoção e a razão (L. L. da Silva, Trad.). Editora Gustavo Gili. (Trabalho original publicado em 2000) [ Links ]

ILGA Portugal [ @ilgaportugal]. (2021, 25 de novembro). Dia 25 de novembro - Dia Internacional de Eliminação de Todas as Formas de Violência Contra Todas as Mulheres [Fotografia]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWtZ9LTNvFf/ [ Links ]

Kuperman, D. (2019). Fanzine feminista Noiz: Design como artivismo [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade de Lisboa]. Repositório da Universidade de Lisboa. http://hdl.handle.net/10451/38918 [ Links ]

Lamartine, C. (2021). “Nem tudo tem de ficar entre 4 paredes”: Ciberfeminismo e violência doméstica em tempos de pandemia. Revista Comunicando, 10(1), 2-39. [ Links ]

Lamartine, C., & Cerqueira, C. (2022). “Caladas nos querem, rebeldes nos terão”: Ciberfeminismo e interseccionalidade na construção híbrida do movimento 8M em Portugal.Observatorio (OBS*), 16(0), 119-138. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS16Special%20Issue20222292 [ Links ]

Lei n.º 112/2009, de 16 de setembro, Diário da República n.º 180/2009, Série I de 2009-09-16 (2019). https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/lei/112-2009-490247 [ Links ]

Lessa, P. (2015). Visibilidades y ocupaciones artísticas en territorios fisicos y digitales. In N. Padrós, E. Collelldemont, & J. Soler (Eds.), Actas del XVIII Coloquio de Historia de la Educación: Arte, literatura y educación (pp. 211-224). Universitat Central de Catalunya. [ Links ]

Liga Feminista do Porto [ @ligafeministadoporto]. (2021, 25 de novembro). A Liga Feminista do Porto surge em Maio de 2020, derivado da necessidade de ocupar um espaço de organização e mobilização das mulheres no Porto, pela reivindicação e luta contra a opressão patriarcal e os seus contornos de violência machista [Fotografia]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWrYbIGoyS8/ [ Links ]

Machado, I. de A. (2019). Experiências estético-dialógicas em arte-ativismo. ARS (São Paulo),17(37), 45-74. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.21780447.ars.2019.159755 [ Links ]

Magalhães, S. I., Cerqueira, C., & Bernardo, M. (2012). Media and the (im)permeability of public sphere to gender. In M. Nunes da Costa (Ed.), Democracy, mass media and public sphere (pp. 35-52). Edições Húmus. [ Links ]

Martinez, F. (2019). Feminismos em movimento no ciberespaço. Cadernos Pagu, (56), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449201900560012 [ Links ]

Mesquita, A. (2011). Insurgências poéticas: Arte ativista e ação coletiva. Annablume Editora. [ Links ]

Neves, S., & Costa, D. (Eds.). (2017). Violências de género. CIEG/ ISCSP-UL. [ Links ]

Offen, K. (2008). Erupções e fluxos: Reflexões sobre a escrita de uma história comparada dos feminismos europeus, 1700-1950. In A. Cova (Ed.), A história comparada das mulheres (pp. 29-45). Livros Horizonte. [ Links ]

Oliveira, P. (2019). A quarta onda do feminismo na literatura norte-americana. Palimpsesto, 30, 67-84. https://doi.org/10.12957/palimpsesto.2019.42952 [ Links ]

Parry, D., Johnson, C. W., & Wagler, F. (2018). Fourth wave feminism: Theoretical underpinnings and future directions for leisure research. In D. Parry (Ed.), Feminisms in leisure studies (pp. 1-12). Routledge. [ Links ]

Raposo, P. (2015). “Artivismo”: Articulando dissidências, criando insurgências. Cadernos de Arte e Antropologia, 4(2), 3-12. https://doi.org/10.4000/cadernosaa.909 [ Links ]

Reis, J. S., & Natansohn, G. (2021). Do ciberfeminismo... aos hackfeminismos. In G. Natansohn (Ed.), Ciberfeminismos 3.0 (pp. 51-66). Labcom. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, D. (2017). Lugar de fala. Pólen Produção Editorial. [ Links ]

Sardenberg, C. M. B., & Tavares, M. S. (Eds.). (2016). Violência de gênero contra mulheres: Suas diferentes faces e estratégias de enfrentamento e monitoramento. EDUFBA. [ Links ]

Silva, J. (2019). Feminismo na atualidade: A formação da quarta onda. Jacilene Maria Silva. [ Links ]

Sofoulis, Z. (2002). Cyberquake: Haraway’s manifesto. In A. Cavallaro, A. Jonson, & D. Tofts (Eds.), Prefiguring cyberculture: An intellectual history (pp. 84-101). The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Stubs, R., Teixeira-Filho, F. S., & Lessa, P. (2018). Artivismo, estética feminista e produção de subjetividade. Revista Estudos Feministas, 26(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584-2018v26n238901 [ Links ]

Tavares, M. (2011). Feminismos, percursos e desafios. Texto Editora. [ Links ]

Tavares, P. (2008, 22 de abril). Breve cartografia das correntes desconstrutivas feministas na produção artística da segunda metade do século XX. Arte Capital. http://www.artecapital.net/opiniao-64-paula-tavares-breve-cartografiadas-correntes-desconstrutivistas-feministas [ Links ]

UMAR ::: Associação Feminista [@umar_feminismos]. (2021, 25 de novembro). Segundo o Observatório de Mulheres Assassinadas da UMAR, entre 1 Janeiro e 15 de Novembro de 2021 foram assassinadas 23 mulheres em Portugal [Fotografia]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWqvhxCMOGa/ [ Links ]

Walker, L. (1999). The battered woman syndrome (2.ª ed.). Springer. [ Links ]

Received: December 07, 2022; Revised: December 21, 2022; Accepted: December 21, 2022

text in

text in