Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

versão On-line ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.12 Braga dez. 2023 Epub 30-Jan-2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.4626

Varia

The Dialogue Between a Film and Its Spectator: Gaining Freedom

1 Faculdade de Belas Artes, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

Neste artigo, pretende-se refletir sobre a importância do espectador na construção de um processo dialógico com um filme. Para isso, parte-se da aparente necessidade de desconstrução dessa relação que, se inicialmente, pode ser vista como duas esferas interseccionadas, aos poucos tende a fundir-se em apenas uma, a ser rompida. Para a realização dessa análise, foi levada em consideração o ponto de partida da arte ou, em outra medida, a visão do artista, para que tais esferas sejam o reflexo de entendimentos subjetivos, mas claros, e para torná-las, de facto, visuais a partir de tanto. Nesse sentido, encontrou-se em Rancière (2008/2010) uma das perspetivas que considera um novo lugar para o espectador, o de “ativo cocriador”, com o poder de subverter as hierarquias estabelecidas e transformar a relação de poder entre a obra e o público. Simultaneamente, Bazin (1958/2014) pensa que o cinema é uma forma de representação da realidade que permite ao espectador experimentar a sensação de estar presente no mundo retratado na tela. Ora, a questão parece encorpa-se, ainda, ao explicitar-se a importância da sensação, do prazer estético, algo defendido por Sontag (1966/2020). Por tudo isso, parece necessário conceitualizar imageticamente as individualidades e como estas podem ser, minimamente e em caráter subversivo às proposições dos autores citados, direcionadas, para que o espectador se torne, de todo, parte do filme e possa sentir-se importante ao se dar conta de que faz parte do resultado: é quando se rompe a esfera final de dentro para fora, possibilitando uma experiência única de liberdade.

Palavras-chave: experiência estética; visão do artista; espectador cocriador; subjetividades direcionadas

This article explores the significance of the spectator's role in shaping a dialogic connection with a film. It is rooted in the discernible need to deconstruct this relationship, which, although it may initially appear as two intersecting spheres, gradually tends to merge into a single one, requiring disentanglement. In this analysis, we considered the inception of art, or the artist's vision, to ensure that these spheres reflect subjective yet distinct interpretations and effectively make them visually evident from that point onward. In this vein, Rancière (2008/2010) provides one perspective that considers a new role for the spectator, an "active co-creator" who can subvert established hierarchies and transform the power dynamic between the artwork and its audience. Bazin (1958/2014) also believes that cinema is a portrayal of reality that grants the spectator a sense of presence in the world depicted on the screen. This perception seems to be amplified by the significance of sensory experience and aesthetic delight, an idea advocated by Sontag (1966/2020). For all these reasons, it seems necessary to conceptualise individualities through imagery and explore how they can be, subtly and subversively to the propositions of the authors mentioned, directed so that the spectator becomes truly part of the film and can feel important as they realise they are part of the outcome: this is when the final sphere is broken from the inside out, enabling a unique experience of freedom.

Keywords: aesthetic experience; artist's vision; co-creator spectator; directed subjectivities

1. Introduction

Film is an inexhaustible source of expression, providing more than just a linear narrative; it presents a universe teeming with dialogues, emotions, and ideas conveyed through a unique language. This study introduces an innovative approach to understanding the complex interaction between film and spectators by introducing two spheres of interpretation: the sphere of non-formal understanding, encompassing the explicit and factual content presented, and the sphere of formal understanding, which focuses on the underlying and expressive elements that transcend the apparent content.

The originality of this study lies in the way these two spheres are integrated and applied to analyse the cinematic experience, considering the spectator's subjectivity and the coexistence of literal and expressive interpretations. This possibly innovative approach builds on the theoretical tradition of prominent scholars in the field of film studies, allowing for a profound discussion of the complex nature of cinematic art.

The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) is analysed as a case study, focusing on the film's opening scene. The analysis delves into how the subtleties of formal and non-formal understanding become evident and contribute to establishing the narrative. Here, the originality of the proposed spheres is revealed through the thorough analysis of the interaction between the literalness of non-formal understanding and the expressiveness of formal understanding.

The conversation then extends to the concept of art as a mimesis of reality, extending the debate with Susan Sontag's (1966/2020) insights on the subject. This particular further highlights the study's originality, bringing new perspectives on how mimesis, seen through the lens of the proposed spheres, influences the overall perception of an artwork.

The multidimensional nature of film appreciation is another theme explored in this article, portraying the complexity of the interactions between form, interpretation and the spectator's experience. Jacques Rancière's (2008/2010) thoughts on the nexus of art and politics are drawn here to explore the mutual influence of the spheres of appreciation.

Moreover, the article integrates the cinematic theories of Bordwell and Thompson (1979/2013), examining how techniques like shot sequencing and camera placement can shape the perception of the artwork. Through an analysis of the film Boksuneun Naui Geot (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance; Park Chan-wook, 2002), this article argues that film is a delicate balance between various worlds, forming a universe of its own.

In essence, this article establishes a profound dialogue between film and the spectator, exploring film's ability to elicit multiple sensations and interpretations. This study extends an invitation to perceive film not just as a vehicle for storytelling but as a vital space for exploring emotions, sharing experiences and contemplating reality - a reality of which film itself is an intrinsic component. It is anticipated that the originality and dedication to rigour within this research, grounded in the well-established theoretical tradition of published studies, will contribute significantly to enhancing our understanding of the proposal of individual freedom - explored through a brief final analysis drawing from the film Johnny Guitar (Ray, 1954) in the light of Rancierian thought -, provided by film and, consequently, its impact on our world - which is as individual as it is plural.

2. The Spectator as a Destination

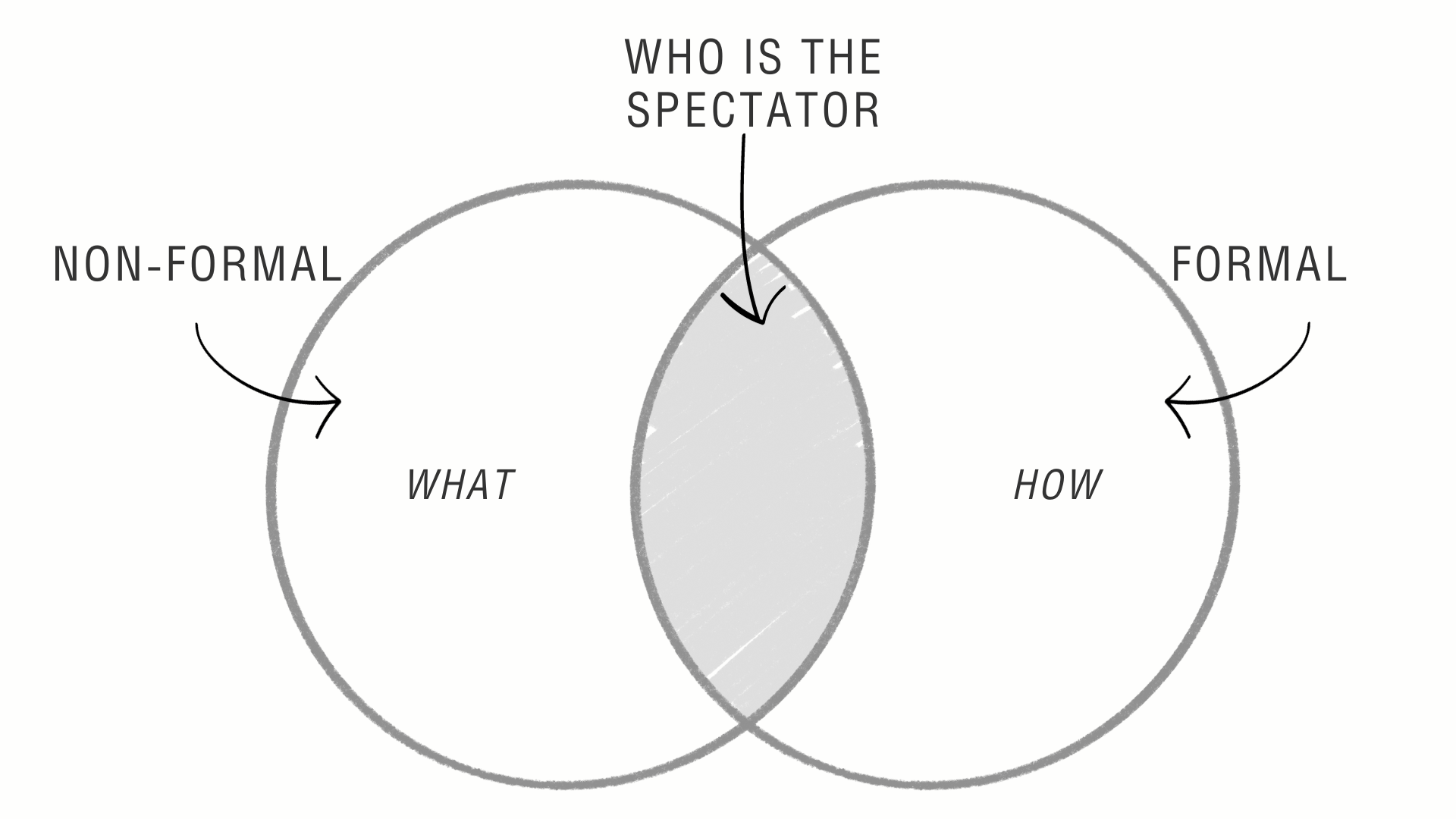

Fundamentally, every dialogue between a film and its spectator unfolds within two specific spheres: one encompassing non-formal understanding and the other formal understanding (Figure 1). In practical terms, the former resembles a conversation between two people where facial expressions, gestures, glances, or the intensity of speech hold little significance; everything operates quite literally, akin to a textual conversation in which the intention behind the written words takes a back seat to the literal functionality of those words. Formal understanding, therefore, is exactly the opposite: it lies in how the words are said, the smallest pauses between them, and the gestures that drive the intentions. As much as the inclination is towards a more straightforward literal conversation with a film, and one is unaware of this second sphere, it is there to provide a balance. Even assuming that these spheres affect each spectator in different and subjective ways.

Figure 1 For the process of metamorphosis, the balanced experience between the non-formal sphere and the formal sphere

So, it is conceivable not to understand the story of a film; it is possible not to understand specific situations within a film. However, evading the paths designed for formal appreciation can prove almost impossible. That is because the form of a work is intrinsic to the work itself. It operates despite its literal functionalities.

Based on that premise, the opening scene of the film The Conversation (1974), which underpins the entire work (00:00:00-00:03:10), is a clear example. Providing a literal description of the events is easy; in other words, the non-formal understanding is simple and recounting the sequence of facts poses no challenges.

The scene shows a square from a high-angle shot1. The shot gradually closes in on a mime who is performing. He eventually becomes the protagonist of this moment. Then, after following a man more intensely - mimicking him like a shadow - the subject says goodbye to the spectator with a leap, and the spectator begins to follow the man being mimicked.

Susan Sontag (1966/2020), in her essay "Contra a Interpretação" (Against Interpretation), refers to mimesis in art, remarking that "the earliest theory of art, that of the Greek philosophers, proposed that art was mimesis, imitation of reality" (p. 15). However, aside from the presence of the mime in the scene, it might be important to realise that he essentially exists solely within the context of that moment and is apparently irrelevant - non-existent - at the end of this opening. Only apparently, because his "non-existence" relies on one existence for form, it is formal; it brings the symbolism of the silence required for the work of the film's protagonist, and by dressing in black and white in a colour film, it conveys the "simple existence", a "pure presence of being", giving the "character" of the work, something like André Bazin (1985/2006) said about Charles Chaplin's Charlot:

before having a "character" and that coherent and closed biography that novelists and playwrights call Destination, Charlot simply exists. He is a black-and-white form imprinted on the silver halide crystals of the orthochromatic film. This simple existence, this pure presence of being, is the most precious thing the author of The Kid has to offer us. (p. 37)

However, the complete depiction of the scene is nothing more than what is visually seen. Additional details can be included, such as the estimated number of people in the square, the mime's imitation of a dog (00:01:30-00:01:35), and the realisation that one side of the square is bathed in sunlight while the other lies in shadow. These details all pertain to the visual aspect - what is physically visible, what tangibly exists.

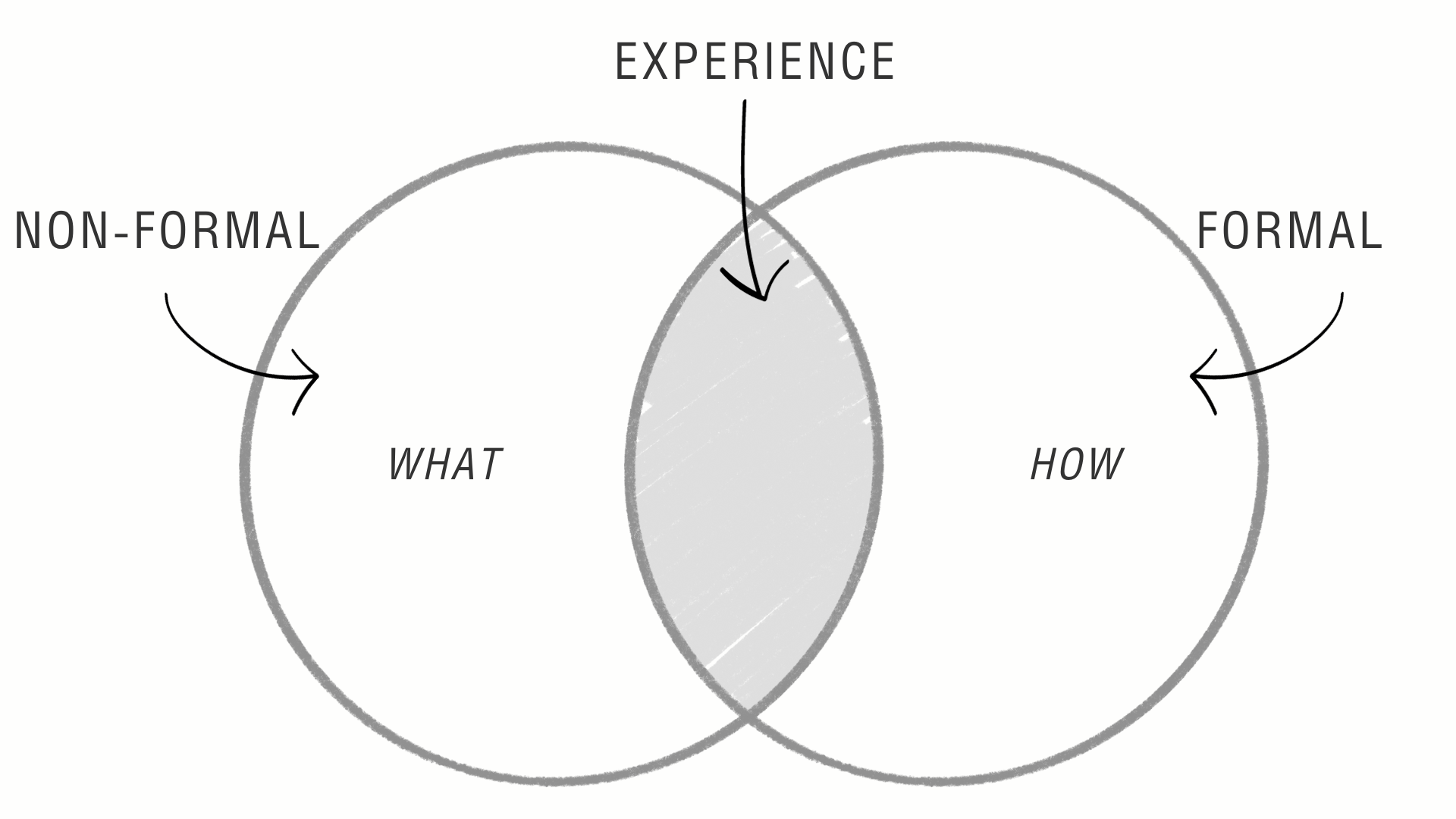

On the other hand, there is the how of this tangible display (Figure 2). The how can give the spectator the tools to merge their established non-formal understanding with the form devised by a film's director. This form encompasses everything intended to evoke sensations. Even so, as mentioned, the sensations idealised may or may not materialise. This is because it is not a literal construction but a subjective one that will resonate with a multitude of people (the audience), each with different education, backgrounds and life experiences; it is a subjectification at the disposal of the spectator and who they are in the broadest sense; it is, above all, a political subjectification.

About this contact, Jacques Rancière (2008/2010), in O Espectador Emancipado (The Emancipated Spectator), offers fresh insights into the topic by exposing a form of connection between art and politics:

art and politics are connected as forms of dissent, as operations to reconfigure the common experience of the sensible. There is an aesthetics of politics in the sense that the acts of political subjectification redefine what is visible, what can be said about the visible and which subjects are capable of doing so. (p. 95)

Nonetheless, subjectivity is consistently constructed by formal elements. They are part of the film language and were established by D.W. Griffith (1915) with The Birth of a Nation, further enhanced and consolidated by Orson Welles (1941) with Citizen Kane. These seemingly well-established and comprehensive elements continue to evolve - especially as we have yet to fully comprehend the film's full potential, given its relatively short yet intricate history.

In The Conversation, the images' formal experience can enhance the whole film's perception, even if this whole is not homogeneous. The short introduction shows an almost hypnotic connection between the conception of the director, Francis Ford Coppola, and the spectator, preparing them for the development. Thus, everything is handled with a planned slowness: the image fades in, and from the high-angle shot, there is a zoom-in towards the mime.

Indeed, there are no cuts throughout the scene - which could be fuelling its hypnotic content. The square, shaded on the right, guides the spectator's gaze to the sunny left. That is where, by zooming in and moving the character differently, the mime will be found among the bustling crowd in the gradual, uncut closing shot.

Meanwhile, the music escalates in volume to draw the spectator into what is being seen and transforms what is being watched. From this perspective, everything remains in sync: the image gradually fades in and continues to zoom in as the music commences softly and progressively crescendos. These parallel and repeated connections across multiple layers (the visual image's emergence, its movement, and the progression of sound) are fundamental to hypnotic power.

Bordwell and Thompson (1979/2013), commenting on uncut shots' effects, confirm this option's immersive power. They say that sequence shots are particularly effective in creating a sense of realism and immersion for the spectator, as the use of a single continuous shot can give the impression that the action is unfolding in real time before our eyes.

There is also the power relationship between the right and left of an image and how this can influence the spectator's comprehensive perception or emotional response - even without conscious rationalisation of what has been watched. That is because there is a rule of thumb, based on numerous psychophysical observations, indicating that the elements in the right half of the scene are perceived more quickly and with greater accuracy than their counterparts in the left half of the scene when the images are presented in an unobstructed perspective (Grossberg & Mingolla, 1985).

Thus, by choosing to film with natural light during a time of day when shadows shroud the right side, Coppola guides the spectator's gaze toward the left side, implying an unnatural perception process for the spectator.

In the next sequence, when the spectator has already established a connection with the mime's performance and is closely observing, the mime moves to the lower left corner of the frame, finds the individual who will become the main character and mimics him (00:02:15, 00:02:22). The mime then starts following the man towards the top right. The mimicked man speeds up his pace, interrupting the hypnotic slowness of the initial proposal and stepping to the right, leaving the mime on the left (00:02:35-00:02:46). At this point, the camera stops following the mime and starts following the man - played by Gene Hackman. The imitator says goodbye with a single leap (00:02:56-00:03:00) into non-existence. Finally, the opening credits end with the real protagonist taking his place after the imagery game.

At this point, it is already clear how non-formal understanding differs from formal understanding. Whereas the former is associated with what is followed within the narrative, or more plainly, the story and nothing else, the latter, as mentioned, pertains to how it is seen and shown. The first is a process outlined in the script; the second is the director's work. While one aims to tell a story, connect the threads, and ensure that dialogues (when they exist) make sense within the context, the other will look for expressive ways to make this happen, seeking to enhance the dynamics of sensations through language, be it consolidated or experimental.

Nevertheless, it can be reaffirmed that, prior to the intended deconstruction, there is an understanding that appears to reside at the crossroads of the formal and non-formal spheres, acting in its own way and distancing itself from the regimentation of artistic desires: the inherent individuality of each spectator. But there must be a dismantling of this understanding, a loosening of the boundaries between the spheres, because, as Rancière (2008/2010) suggests,

so, there is an art-related politics that precedes the politics of artists, an art-related politics as a singular distribution of the objects of shared experience, which operates independently of artists' intentions to support particular causes. (p. 96)

Based on the director's suggested forms of understanding and their connection with the spectator, subtexts that transcend these can be brought to light. These subtexts are part of the interpretation, and any interpretation can be personal and unique and, therefore, should not be the focus of any argument about a film. Hence, it is imprudent to regard the literal content as the ultimate result; likewise, formal skill alone cannot be deemed the complete work. It is in the middle (initially). That is because an approach to art-as-being operates with the distinctive fruition of singular and non-transferable elements, even if they originate from a collective experience. In this case, it is the remarkable approach of art-as-being that is capable of breaking the spheres. On the other hand, the life stemming from the multiple gazes, thereby making a film as multiple as its spectators, cannot be taken as the fulfilment of the work, especially when this life emerges from the interpretation of the proposed non-formal sphere that is frequently the case.

Sontag (1966/2020) is even more assertive regarding the multiple possible substances of one work and the constraining nature of interpreting it. She says that

[the] overemphasis on the idea of content entails a perpetual and always inconclusive project of interpretation. This habit of approaching artworks in order to interpret them reciprocally sustains the illusion that there is, in fact, something which is the content of an artwork. (p. 18)

Additionally, upon revisiting the opening scene of The Conversation, the mime's presence can serve as a symbol that adds value to the whole, even if there is no subsequent physical participation in the remainder of the film. One of the symbols is thematic, as previously mentioned, considering Hackman's character's occupation in surveillance - which inherently involves silence. There is also a sensory symbol with the same practical importance: Coppola relates the characters through imagery by choosing the gradual zoom-in. Such an approximation can sensorially lead to an unconscious cause-and-effect relationship, as in the anchoring effect. This suggests that how a stimulus is presented can influence how it is perceived, prompting associations with other information (visual or otherwise) present within the same context (Bargh et al., 1996). A more explicit example might be showcasing a model alongside a skincare cream: forming an association between her seemingly flawless skin and the product's potential results is nearly immediate. Coppola makes this connection between the mime and the real protagonist. When the mime ceases imitating and exits the scene, crossing an invisible boundary, the portrayal of a character that unfolds through form, the formal sphere, comes to an end: there is the partial unveiling of an identity; the simple action of the new man becoming the centre of attention by walking alone against the crowd can convey or replicate his inner discomfort; eventually, the diegetic silence connecting him to the mimic is broken when voices that are part of his professional investigation are heard. This whole process acts as interferences in the plot that are certainly open to rationalisation but are felt within the aesthetic experience, the spectator being the destination of the chosen process.

3. The Spectator as a Path

Meanwhile, it is possible to continue deconstructing the spheres - or weaken them - by saying that the dialogue between spectator and film within the sphere of non-formal understanding is indivisible, that is, whether or not one understands what actually happens, the story that is told (when there is a story). There is no need for sensations to convey anything or for any interpretation to assimilate the scenes. However, the sphere of formal understanding is subdivided into two layers: that of sensations and that of interpretations (so contested by Sontag), both of which can contain dozens of nuances.

The layer of sensations is induced by the use of form, by how the director crafts the scenes to generate a sensory experience. Every emotion felt while watching a film arises from the director's connection to the script and how this connection translates what, before filming, was text. The second layer, that of interpretations, like the first - but especially so - transcends the films and encompasses each spectator's personal, human, social and political experiences. Furthermore, when this layer transcends films, it does not concern the artwork but only its interpreter. Thus, it is the only aspect almost entirely beyond the creator's control, regardless of

some artists' strategies aimed at transforming the boundaries of what is visible and expressible, who want to allow what was not seen to be seen, to make what was seen too easily to be seen differently, to relate what was seemingly unrelated, all to produce disruptions in the sensitive fabric of perceptions and the dynamics of affections. (Rancière, 2008/2010, p. 97)

That seems to flow from one of film's many possible tributaries, the idea that a film has no obligation to tell a story or convey something tangible. As art, what a film truly requires is to remain receptive to experiences. Together, these experiences can derive from a work containing a classic story - with a well-defined beginning, middle and end set out in its acts - or they can also be the result of a work with no intention of conveying anything.

Therefore, the relationship between spectator and film may be searching for further development. As film is a recent art form, it is reasonable that the experience of watching a film draws upon the influences of other arts, particularly literature and painting. Liking or disliking a film solely based on its story suggests an approximation to a kind of appreciation/report - one that is available to perceive what the film tells (the non-formal sphere) and what it means by what it tells (interpretation, a layer of the formal sphere), nothing more.

There is, in completeness, the filmic space, encompassing everything that the spectator can see and what is not visible. The whole experience felt by the spectator can be more complex than what is not exposed. The reason may be simple: while the visible filmic space has only one layer - exactly everything that is seen - the non-visible encompasses six subdivisions. These are: what is above, below, to the left and right of what is seen - beyond the edges of the image - and what is in the position of the camera or behind it, in front of the image, and what is behind the scenery, characters and objects. In practice, what is seen is like a painted canvas in motion, and what is not seen is the entire three-dimensional universe surrounding it. As such, there is much more to be explored through what cannot be seen.

Some filmmakers skilfully harness the non-visible filmic space to evoke sensations and feed the conversation between spectator and film. Park Chan-wook, for example, is a contemporary director who uses this space like few others. In his Boksuneun Naui Geot, the opening scenes can even build a relationship of guilt with the spectator. One particular sequence underscores this connection vividly as it depicts four young men (the visible space) listening, through a wall, to a woman's moans (who is in the non-visible space) while masturbating (00:09:45-00:10:01). The camera slides sideways to unveil the woman (00:10:01-00:10:14). At this point, we discover that her moans are of pain (due to a kidney crisis). The camera slides a little more until it reveals the woman's brother in the foreground - the protagonist - who is deaf and, even though he is in the same room, cannot hear her pain, which is still visible to the spectator (00:10:14-00:10:26).

This interaction with filmic space can manifest in many other ways. Whether through depth of field, notably demonstrated in Citizen Kane, or to create suspense, masterfully used by Alfred Hitchcock, or even to establish analogies of significance among the characters. In this respect, the closer someone is to the camera and in visible space, the more relevant they are compared to those farther away from the camera and in visible space. All these elements imply that the spectator's formal understanding, even if they are not acting consciously, is being nurtured and built in a relationship with the filmic space and, ultimately, with the film itself.

Hence, I believe the power of film primarily resides within the spectator. Not because of any ineffectiveness in the art form but because, as Salomé Coelho (2013) suggests, "cinema's potential for intellectual emancipation lies in its idleness" (p. 13). This idleness pertains to the opportunity for contemplation, the capacity to engage in an aesthetic experience that facilitates reflection and serves as a path toward intellectual emancipation - which is certainly the opposite of the unstable daily immersion that usually affords little room for stable contemplation, including emotional stability.

Moreover, film, which is more aware of its narrative, possibly reflects the need to remedy the paradoxical instability engendered by routine. Thus, it emerges as an art form that aims to be an explicit - political, moral and knowledge - guide. Coelho (2013) prompts this reflection by commenting on this process and drawing a distinction with the spectator's reception: "film, as an art form, should not and does not address 'politics, morality or knowledge', although it cannot disassociate from the relationship with a purpose (to enable justice); film, as art, is pure openness to the other" (p. 13).

Even so - and I think this is obvious - everything has a more direct effect when something is to be told. An experience on its own is still an experience but paired with a narrative, it can become much more vivid. Looking back to the scene in Boksuneun Naui Geot, the sight of young men masturbating and the realisation that what they were hearing in the non-visible space were moans of pain, not pleasure, then the revelation of a man with his back turned to the suffering woman as if indifferent to her agony, are moments that evoke a multitude of sensations. However, understanding this scene and realising that the man with his back turned is deaf, that he is her brother, and, as the film unfolds, following him as he goes to great lengths to get a kidney transplant, can be a more straightforward experience, without the need for major interpretations.

The connection between what there is to tell and what there is to say with what there is to show and what there is not to show must be the most complex aspect of the filmic experience. It is the combination of content and form. Even so, if the content is somehow incomprehensible, the form is there to cause sensations. As mentioned, it is conceivable not to understand the story of a film; it is possible not to understand specific situations within a film. However, evading the paths designed for formal appreciation can prove impossible. Reiterating, the form of a work is intrinsic to the work itself, transcending mere literal functionalities.

4. The Spectator as a Character

Moreover, if we consider that "the real is always the object of a fiction, that is, of a construction of the space where the visible, the sayable, and the doable are intertwined" (Rancière, 2008/2010, p. 112), a final relationship must be forged between the genuinely real (the spectator with their potential and capability for emancipation) and a figure who is unequivocally fictional. That said, there is a construction between non-formal and formal understandings that, among many, can encapsulate what has been discussed so far: the construction of the character Old Tom (played by John Carradine) in the film Johnny Guitar (Ray, 1954). He (Old Tom) can be seen as a spectator in the film. Although he is initially in a small room and has contact with the protagonist, Vienna (Joan Crawford), through a window, that same window serves to locate him exactly as someone watching her steps.

Nicholas Ray's (1954) direction in Johnny Guitar becomes particularly notable in its fusion of the visible and non-visible aspects of the cinematic form with the external space of the spectator's self-awareness. This is exemplified in the poignant words of Old Tom just before his death: "nobody notices me. I'm just part of the furniture" (01:08:15-01:08:19). This surrender, akin to becoming part of the furniture, is essential when engaging with the fullness of an art form like film. Whether in a theatre, your own home, or any setting, this surrender allows for a genuine and comprehensive dialogue with everything that is non-formal and formal. Perhaps the emancipation of the spectator lies in recognising that the potential for emancipation exists when you allow yourself to be carried away. Because "there is no real in itself, but rather configurations of what is given to us as our real, as the object of our perceptions, our thoughts and our interventions" (Rancière, 2008/2010, p. 112). This is the freedom proposed by film.

Otherwise, in the middle of the path, watching a film by actively contemplating and deciphering it as if reading a textbook is to be trapped. Hindering the full expression of a film's subjectivity, preventing one from realising that what unfolds on screen constitutes a self-contained universe with its own inherent rules, detached from the constraints of ordinary reality (since there is no absolute real, “but rather varying configurations of what is presented to us as reality”; Rancière, 2008/2010, p. 112) is to be trapped in a world that is too exact. No art form can ever be an exact entity.

Then the spectator can finally realise that they are part of the film - from their own external space - and feel like Old Tom's last words: "look! Everybody is looking at me! It's the first time I ever felt important" (01:16:10-01:16:20). In a nutshell, every spectator's role is fundamentally about becoming a part of the film, regardless of the duration, whether it's just one, two, three, or four hours.... sometimes more. What matters most is the outcome of the conversation between the film and its spectator (Figure 3). This outcome can be extraordinary when non-formal and formal understandings ultimately converge, giving rise to a sphere that shatters and opens up to boundless possibilities, ushering in a distinctive experience of freedom.

5. Conclusion

This study has delved into the complex and multi-layered relationship between film and spectator, providing a comprehensive analysis encompassing both formal elements and filmic content. The initial emphasis was examining the film The Conversation, using it as a case study to analyse the interaction of non-formal and formal spheres and subsequently bringing underlying subtexts and political possibilities to light.

These spheres outlined in this study offer a fresh perspective for understanding the relationship between film and the spectator. They allow for complex visual analysis, acknowledging that the spectator is not a passive recipient but an active agent, as Jacques Rancière (2008/2010) proposed, who interacts with the film in multiple layers of understanding.

The figure of the spectator is also presented as a destination, a path and a character, becoming a central element in the filmic experience. As a destination, the spectator is the film's ultimate goal, the recipient for whom the narrative is constructed and whom the art of film seeks to reach. In this sense, every choice in film production is made with the spectator's experience in mind, as if every film element were aimed at them. As a path, the spectator is how the work of art comes to life, and their emotions, thoughts and reactions are integral to the process of making sense of the work. Their active involvement in interpreting the work makes it alive and relevant. Lastly, the spectator as character underscores the idea that, through their interaction with the film, the spectator engages in a kind of dialogue with the work, playing an active role in the narrative with their own responses and interpretations, thus creating a scenario rich in multiple meanings.

This study relies on the insights of notable authors such as Rancière (2008/2010), Susan Sontag (1966/2020), David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson (1979/2013). By engaging with and building upon their theories, this research provides a solid and fruitful framework for understanding the interactions between form and content in film, mimesis in art and politics in aesthetics.

In short, the study underscores the significance of approaching film and other art forms with an open and receptive mindset, acknowledging the multiple layers of meaning that can coexist within a single work. It highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of the art of film and explores the potential for interpretation, expression and emotional engagement.

Ultimately, this research encourages further reflection on the role and impact of film on individual lives and society; it is a reminder that art is a dynamic, complex and powerful means of expression and communication, the appreciation of which requires both the sensitivity of the spectator's sensitivity - which remains contingent on their particular availability - and the full extent of the freedom afforded to them through who they - the spectators - are.

REFERENCES

Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 230-244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.230 [ Links ]

Bazin, A. (2006). Charlie Chaplin (A. Telles, Trad.). Jorge Zahar Editor. (Trabalho original publicado em 1985) [ Links ]

Bazin, A. (2014). O que é cinema? (E. A. Ribeiro, Trad.). Cosac Naify. (Trabalho original publicado em 1958) [ Links ]

Bordwell, D., & Thompson, K. (2013). A arte do filme: Uma introdução (R. Gregoli, Trad.; 1.ª ed.). Editora Unicamp. (Trabalho original publicado em 1979) [ Links ]

Coelho, S. (2013). Jacques Rancière e Agnes Varda no intervalo entre cinema e política [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Nova de Lisboa]. run. http://hdl.handle.net/10362/11275 [ Links ]

Griffith, D. W. (Diretor). (1915). The birth of a nation [Filme]. Epoch Producing Corporation. [ Links ]

Grossberg, S., & Mingolla, E. (1985). Neural dynamics of form perception: Boundary completion, illusory figures, and neon color spreading. Psychological Review, 92(2), 173-211. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.2.173 [ Links ]

Rancière, J. (2010). O espectador emancipado (J. M. Justo, Trad.). Orfeu Negro. (Trabalho original publicado em 2008) [ Links ]

Ray, N. (Diretor). (1954). Johnny Guitar [Filme]. Republic Pictures. [ Links ]

Sontag, S. (2020). Contra a Interpretação e outros ensaios (D. Bottman, Trad.). Companhia das Letras. (Trabalho original publicado em 1966) [ Links ]

Welles, O. (Diretor). (1941). Citizen Kane [Filme]. RKO Radio Pictures. [ Links ]

Received: March 04, 2023; Revised: June 28, 2023; Accepted: June 28, 2023

texto em

texto em